Happy Birthday, Tony Williams! Today, Tuesday, December 12, the drummer/composer would have turned 79.

I can’t say it any better than my friend Ethan Iverson did in his brief and beautiful post on the passing of trumpeter/composer/bandleader Herb Robertson:

“Nothing can compare to first love. As we get older, it becomes ever more obvious that what we took in when we were young influences us forever.”

Amen, amen.

The Tony Williams Quintet featured a front line of Wallace Roney on trumpet and Bill Pierce on saxophones, while the rhythm section was built around pianist Mulgrew Miller, with several wonderful bassists— first Charnett Moffett, briefly Bob Hurst, and finally Ira Coleman— in the group at various times.

This was a great band. Busy in clubs, concert halls, and festival stages from 1986 to 1993, they made six full-length albums for Blue Note that were well-received and are streaming on all the major services. But it’s sobering, strange, and sad to realize that in addition to Tony, Mulgrew Miller, Wallace Roney, and Charnett Moffett are no longer with us.

Jazz, as vital and healthy as ever, thankfully continues its forward march. There is more music to be made, more work to do. But Tony’s quintet was one of my first loves. What would “going forward” mean without the things most important to you?

Williams was born 12/12, and I was 12 when I heard The Story of Neptune, the group’s final studio release. So here’s 12 tracks of Tony and his quintet.

Playlist is here, individual tracks below.

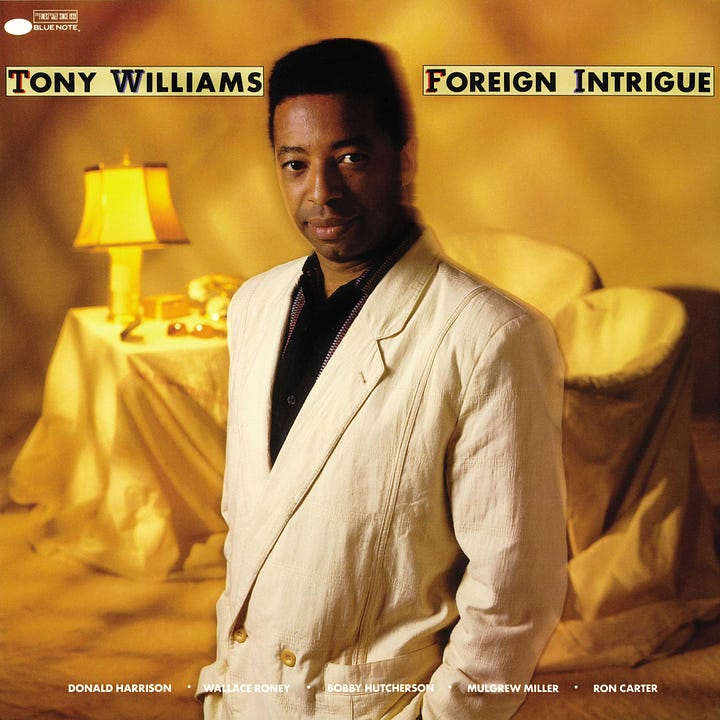

“Clearways” from Foreign Intrigue (Blue Note, 1986). Tony assembled a sextet for Foreign Intrigue, his first-ever straight-ahead jazz date as a leader. The original idea was a meeting of the old guard— Williams, bassist Ron Carter, and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson— with three-fifths of the Terence Blanchard-Donald Harrison quintet: Blanchard, Harrison, and pianist Mulgrew Miller. When Blanchard became unavailable, trumpeter Wallace Roney stepped in, and the outline of what would become the Tony Williams Quintet was in place.

Tony’s intro to “Clearways” is charismatic and badass: rudiments and truth in a swinging and uncompromising package. He and Carter, the smoothest, fastest ride in history, set up the groove for Williams’s melody to unwind over 50 bars. It’s a challenging form that Bobby Hutcherson and Mulgrew Miller bravely navigate.

“The Slump” from Civilization (Blue Note, 1987). Tony’s singable, gospel-tinged theme suggests Horace Silver and Cannonball Adderley, boyhood heroes of the drummer/composer. The melody keeps erupting with drum comments, and then settles into statements from Moffett, Miller, and Pierce, with Williams alternating between swinging accompaniment and solo-like statements. No matter how bold or assertive Williams is, he’s not disruptive. Everyone understands each other. This is a real band.

“Red Mask” from Angel Street (Blue Note, 1988). This tune was a highlight of the band’s gigs: after a long intro, Tony would then cue the band in by playing the intro heard here, a signature Williams lick of alternating right hand/right foot, distributed melodically around the kit. Another tricky Williams form of 31 bars (by my count) which Pierce, Roney, and Miller all contend with.

There’s something else here as well. For the first time, starting with Wallace Roney’s debut as a leader, Verses (Muse, 1987), on which Williams played and acted as producer, and throughout Angel Street and beyond, Roney began consciously and deliberately evoking Miles Davis. This reflected both Roney’s growing personal and musical closeness to Miles and Tony’s embrace of his own legacy. Respect.

“Obsession” from Angel Street (Blue Note, 1988). Jack DeJohnette describes “Takin’ Off”, the themeless minor blues from Forces of Nature, as “having that pull”— the fast tempo becomes a vortex, and the everyone gets sucked into it. That pull is evident on the thrilling, wild “Obsession”, the band just hanging together, Tony’s thunder nearly overwhelming his young charges. Listening anew for this post and marveling at the Tony’s chops, what was most evident was that Williams’s technical excellence was united with his gift for reaching listeners.

“Native Heart” from Native Heart (Blue Note, 1990). I love the feel of the rhythm section here— an open quasi-bossa nova, with Williams asserting his conception with smiling confidence, and Miller’s comments around the melody are a highlight. I don’t love the Native Heart cover— I don’t think we need these images. But I think the music is important and valuable, so I overlook it, and hope you can too.

“City of Lights” from Native Heart (Blue Note, 1990). A great melody with a rhythmically deceptive intro: piano, bass, and horns sounds like they’re hitting beat 1 with Tony’s crash cymbal, but when the melody proper begins, what we thought was beat 1 is revealed to be beat 2! Williams smoothly integrates the lessons he learned in fusion and rock into a rich, nuanced, mature conception. He’s no longer an 18 year-old genius, he’s a 45 year-old grand master. Mulgrew Miller nearly steals the show yet again, and Roney’s Miles references, which reflect an evolving intra-band dialogue between Roney, Williams, and Davis himself, are now a part of the music.

“Juicy Fruit” from Native Heart (Blue Note, 1990). What a feel, what a shuffle— it brings the listener right in, exciting, relentless, adult. What a great arrangement too, with Wallace and Bill Pierce exchanging choruses instead of soloing at length, and coming back to the tune’s signature lick. Tony sounds like he’s smiling the whole time.

“Two Worlds” from Native Heart (Blue Note, 1990). Originally recorded by Lifetime with a vocal from Jack Bruce, the star of this track is Robert Hurst, pushing the beat with Tony as they create some pull and extract real fire from soloists Pierce, Roney, and Miller.

The group’s next album, The Story of Neptune, was their final studio recording, and for me, their most satisfying. It includes a multi-part “Neptune Suite” (“Overture”; “Fear Not”; “Creatures of Conscience”) that represents a new level of compositional ambition and skill for Williams, while the rest of the album, save a final Williams tune in the vein of “Juicy Fruit” (“Crime Scene”), was given over to songs by other composers.

Each of the cover tunes seems to represent some part of Tony, some area of feeling and interest— “Blackbird” for the Beatles, “Poinciana” for Ahmad Jamal and Miles Davis, and “Birdlike” for Charlie Parker. The back half of The Story of Neptune must be at least partly autobiographical.

“Blackbird” (Lennon-McCartney) from The Story of Neptune (Blue Note, 1992).

Tony was 18 years old when the Beatles arrived in the States. Perhaps unique in his social and musical circle, Williams was an unabashed Beatles fan, famously installing a huge Beatles poster in his apartment. Williams’ clever setting of McCartney’s melody for a hard bop quintet, with Pierce on soprano and muted Roney, might be the fulfillment of his suggestion to Miles in 1964 that Davis’s quintet tour as an opening act for the Beatles. Tony and bassist Ira Coleman get such a beautiful beat here— for all that stuff Tony plays, it feels like Kenny Clarke and Percy Heath. After the last head, Williams meditates on his cymbals for a moment before bringing the band back in. This is poetry and metaphor— we were only waiting for this moment to arise.

“Poinciana” (Simon-Bernier) from The Story of Neptune (Blue Note, 1992). On “Blackbird”, Williams imagined a peaceable kingdom where the Beatles and the bebop movement are reconciled. Perhaps Williams was continuing that line of thinking by arranging Ahmad’s signature tune for a Miles Davis-inspired quintet. This is one of the quintet’s best and loosest studio performances. Williams’ arrangement is a stand-out, with a new intro vamp, and a precise, gentle reimagining of the melody. Tony’s on brushes all the way, pure folklore and creativity.

“Byrdlike” (Freddie Hubbard) from The Story of Neptune (Blue Note, 1992). Hubbard’s blues is a reference to Donald Byrd, yet Williams spelled it “Birdlike”, pointing us back to Charlie Parker and 1945, the year of Williams’ birth. Up-tempo, exuberant, and joyful, it starts with Pierce and Roney trading and then naturally peaking into a duet. We get a few choruses of Tony and Coleman in lockstep, before Miller swoops in, oblique and unpredictable. Mulgrew goes for a few choruses of science and melody as Roney and Pierce work up to the head, which, when it arrives, feels like a relief. They even include a coda with a final flourish from Williams, letting us hear the beauty of his drums and cymbals, unadorned and pure. It’s a complicated arrangement that the band tosses off without a hitch. With The Story of Neptune, Tony closes the book on a chapter of his musical life.

“Citadel” from Tokyo Live (Blue Note, 1993). For over 9 unaccompanied minutes, Mulgrew Miller examines, considers, and extrapolates on Williams’s melody and harmony. With leisure and patience, Miller picks up a chord, turns it over and around, then keeps moving. It’s a ruminative stroll with some beautiful views, without an obvious high point or central arrival. I’m so glad this is documented, so thankful that Tony featured Mulgrew so prominently showing an aspect of Mulgrew’s art that’s not usually before us. It’s impossible to hear this and not lovingly miss Mulgrew Miller. When the band enters at full blast, somehow it works, not destroying the reflective mood but elevating it. Listen to Williams’ cymbal behind Mulgrew— the line back to Kenny Clarke and Jo Jones couldn’t be more clear. Like McCartney’s blackbird, jazz goes on and on.

Thanks for this.

I saw the quintet in October 1988 in Indianapolis at a club called The Place to Start, which is still operating today as The Jazz Kitchen. (I was in graduate school in Bloomington at the time.) The music was mostly from "Angel Street," which had either just been released or was about to be. I think it was Ira Coleman on bass, but it could have been Moffett. I enjoyed the music, but I will say that Tony played louder that night than any jazz drummer I have ever heard in a straight-ahead context, and there were times when Mulgrew was soloing that he would have been justified in waving a white flag of surrender. I also remember that Tony started the set with a drum solo to set up the first tune, and as he started, a older cat in the audience walked up to the bandstand near the drums, raised a camera and snapped a picture with a bright flash right in Tony's face -- it was startling how rude it was. Tony stopped and shook his head in bewilderment; you could tell he was shocked and angry he was. When he started up again, I felt like he was taking out his anger on the drums a little bit and I wonder, in retrospect, if his volume might have been even louder than usual because he was so pissed.

One other note: Wallace Roney's strong 1987 record "Verses" on Muse is Tony's quintet with Gary Thomas in for Billy Pierce.