Interview with Andrya Ambro

The drummer-vocalist-composer of Gold Dime discusses her cross-genre musical background

All musicians are inspirational to me, no matter what style they play.

Like you, I’m saddened by David Sanborn’s passing. Growing up, I liked his music and heard it often at home, but it was Sanborn’s role on Night Music, NBC’s late-night music show from 1988 and 1989, that hit me hardest.

Produced by Hal Willner, co-hosted by Sanborn and pianist Jools Holland, Night Music presented live performances from musicians of all backgrounds, in every genre: Sun Ra, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Leonard Cohen, the Pixies, Take 6, Sonic Youth, Randy Newman, Dizzy Gillespie, Betty Carter, Tim Berne, Al Green, Dixie Hummingbirds, LL Cool J, and many more.

Sanborn, with a modest, respectful mien, and a keen awareness of every artist’s historical context, introduced the performers, got in a bit of Q&A, and sometimes joined them for a song or two. The quiet humility Sanborn projected summed up the Night Music vibe of easy, unfussy reverence for all music and musicians.

Everyone on the show was treated as a serious artist, and Dave Sanborn was modeling the hippest attitude I know of, one I consciously emulate: he valued quality and intention more than genre affiliation, and saw all music as connected.

I only caught a few episodes, years after it was broadcast, but the Night Music ideal, embodied by David Sanborn, stays with me: we should all talk to each other.

For 20 years, drummer, vocalist, composer, and bandleader Andrya Ambro has been in a category of her own. She is an auteur and innovator who, from the drums, has perfected her own brand of noisy, cinematic, and emotive art rock.

Across two records with Talk Normal, Ambro’s duo with guitarist/vocalist Sarah Register, and three forward-looking and urbane albums with her own band, Gold Dime, Ambro refines and deepens her perspective and aesthetic. Anyone interested in what a contemporary drummer can achieve should know her work.

I’ve been listening to Gold Dime’s stunning recent release, No More Blue Skies, for months. Ambro’s voice and drums are the center of the music, but it’s the detailed arrangements, with guitar and bass in dialogue with Andrya and each other, that bring us to the heart of the songs. We’re lucky to have this music.

As Ambro describes it: “No More Blue Skies feels cinematic: the drums are up front, there’s some soaring string parts and the arrangements are like mini avant-rock operas. It honestly does feel the closest to date I’ve gotten to capturing the soundscape I hear in my head. Proud of it and grateful for my collaborators on it— Ian Douglas-Moore, Brendan Winick, Jessica Pavone, Jeff Tobias and Kate Mohanty”.

“Denise”, the album opener, is a series of contrasting textures and melodies that arrive at a climax, with Ambro’s drums in an Afro-Cuban 6/8. There’s a hint of R&B in Andrya’s elemental beat on “Wasted Wanted” and even a quasi-chorus, albeit one cut with noise and unexpected instrumental dropouts. “We Lose Again” is perhaps the most cinematic and dramatic track, while Ambro’s sly and disquieting spoken-word piece, “Ronnie Desperation”, closes the album on a noirish note.

I’ve known Andrya since a mid-Nineties jazz camp— I rattled on about Tony Williams and she responded with a story of seeing Joey Baron play. She passed me cassettes of stuff I’d never heard: Bill Frisell, Pharaoh Sanders, Art Ensemble, and many others, and it all stayed with me. She’s one of my formative musical influences.

Enthused about her current work and feeling a need to extend the scope of Chronicles, I asked Andrya for an interview. She graciously agreed, and was very generous with her time and thoughts. She and I both heavily revised and edited this piece for clarity and flow.

VS: Andrya, I’m thankful that you’re taking the time to talk. You and I are in different scenes these days, but when I heard No More Blue Skies, I wanted to connect; I feel like we’re on parallel tracks.

First off, I enjoy and greatly admire your music— if I can be a little bold, it’s really ‘future music’: you’re suggesting new possibilities and pointing the way forward, as opposed to expressing an idiom or genre. I can hear some influences, but whatever I hear is fully subsumed into your vision, which is quite an achievement. You’ve got your own voice— I don’t know anyone else making music quite like this.

Gold Dime is far from my typical listening, so I’m learning something, always a good thing. But that’s nothing new, I’ve been learning from you for years! [laughs] When we met as jazz students, you were very aware of a wide range of music, especially avant-garde jazz.

AA: Wow, thank you for those very nice words. I guess I was always going deep into specific mediums in an attempt to educate and develop myself as a young person — be them music, film, or books. I went heavy into jazz; from age 15 to about 18, I desperately tried to understand it and play it. I went in strong! So I guess that’s where I was when we met.

VS: How did you get started in music? Did you start on the drums?

AA: Piano was my first instrument; I took lessons from age six to thirteen. There was a piano at home, and as kids we had to do something artful. My mom said “You can do dance or piano,” I went with piano because I didn’t like the dance outfits.

VS: So your family was musical?

AA: My mom played acoustic guitar in the realm of Joan Baez and Judy Collins, and my father's enthusiasm for music was inspirational to me. The way he would listen to music. He often would lie on the floor with headphones and intently listen to full records, or dance around to it at all hours.

When I was 13 or 14, he brought home this Mahalia Jackson box set, Gospels, Spirituals, and Hymns. I went deep with this and bonded with him on it; I blasted that so much at home and in the car.

And then there was my brother, who’s 8 years older than me and very into music. He got me into Fugazi, who I was obsessed with at ages 12, 13, 14; Dinosaur Jr too. I remember for Christmas when I was 12 he got me the Pixies album Trompe Le Monde. Plus I was into Sonic Youth and obsessed with Nirvana— there was the Dave Grohl factor. [laughs]

Then a friend got a guitar, so I thought “let's make a band and I’ll be Dave Grohl, I’ll play drums”, and my brother kind of talked my mother into getting me a drum kit. She agreed to it as long as I took lessons.

So we got a used Pearl Export 4-piece kit, and I played it all the time in the basement. Eventually they walled me off, cause the TV room was right there, and my family was like “Are you fucking kidding me?” [laughs]

VS: [laughs] Well, if you got the kit, you got lessons. Who was your drum teacher?

AA: At first, and for many years, my percussion teacher was a woman named Helen Carnevale, who was involved in the classical and new music world. She was playing in a new music ensemble called Relache when I met her. She was a pretty intuitive player and was also into Cuban music, hand drums, and other percussion. She was great. She was great with youth. She was a mentor and a friend.

She subbed in for the Philadelphia Orchestra, but wasn’t the typical classical/new music person in that she was fun and didn’t take everything so seriously. She was openly queer, and in the Nineties, that was done out loud far less. I didn’t realize until much later what a unique experience I had.

VS: That’s beautiful. I guess you were learning the usual excerpts and etudes?

AA: Yeah, excerpts on timpani, snare drum, xylophone. I joined the Philadelphia Young Artists Orchestra, a part of the Philadelphia Youth Orchestra which had high school students along with 6th graders who could play the violin like fucking maniacs [laughs]. And yes, to answer your question earlier, I was the only woman in the percussion section in the orchestra, and in my high school concert band and stage band.

I had also started a band with a couple of guitar-playing friends. We did Fugazi covers, then I tried to get them to do Sonic Youth covers, and then we started to write our own songs. Thinking back, my playing was pretty unorthodox.

So I had skills in the classical realm and was attempting drumset in my own unique way. But when I was 16, I decided, “I’m getting into jazz.” My brother had taken a class in college and he got this book called Jazz: History, Instruments, Musicians, Recordings by John Fordham, and I would go to HMV every time I was in Philly, trying to get every record the book mentioned.

VS: I love that book, I could talk about it for hours. What stuck with you from that time, jazz-wise?

AA: I always gravitated towards Monk— I loved his rhythms, the subtle drama of his playing. And then Max Roach, he was the first drummer in that realm where I was like “Oh!” I loved We Insist! Freedom Now Suite and Percussion Bitter Suite, both with Abbey Lincoln. Of course I liked John Coltrane and Elvin Jones, but I was just a kid; as I revisit it now, I realize how much I didn’t understand.

VS: I feel the same— we hear these records as kids and then spend the rest of our lives realizing how deep this music is. So how about shows? Any concerts from this era that stick in your memory?

AA: Around then, I saw Max Roach in a big theater, I loved his hi-hat work. I remember going to see the Sun Ra Arkestra at the Clef Club with my mom in Philly in 1994, right after Sun Ra died, that very brief period where John Gilmore was leading the band. I can’t say I truly understood its greater worth at that point even though I desperately wanted to.

I saw Zorn and Joey Baron when we went up to NYC for the weekend on a family trip when I was 16. My parents were gonna go do something cheesy, and I was like “Can we [my brother, sister, and I] go to the Knitting Factory and see Masada?”

VS: Masada at the Knit in ‘96! Amazing. But how did you get into the Zorn world? From the Fordham book?

AA: I had gotten into more outside jazz because of this guy Aaron Pollack at my high school, a guitar player in our stage band who was into Zorn, Frisell, etc.

Then I started to play random percussion with Aaron and these guys that went to Drexel University. It was hilarious, I’d be playing triangle with them at the Khyber Pass in Philly, or we’d play house shows out in Germantown, PA. No one carded I guess in those days. I really don’t know if the band knew how young I was, I don’t even know if my parents knew what I was doing [laughs].

I need to also mention that that ensemble had this woman who fronted it on vocals/spoken word. Her name was Jenny. She was a wild and compelling performer, I was scared of her and adored her. She was so much more emotionally advanced than all these boys. I still recite some of her lyrics/spoken word in my head. I want to know where Jenny ended up. No idea what her last name was.

VS: I love these stories Andrya— they’re really of a time and place. Can you talk about jazz school? I know you went to NYU…

AA: So I was serious about learning jazz drums, but Helen said “I don’t really do that”, so first I started lessons with Tom Palmer, who taught at the University of Delaware. Then Helen recommended I study with this drummer in New Jersey. This new teacher [whose name we’re leaving out because he shares it with another drummer in an adjacent musical realm] was a heavy player and was jamming with famous jazzers when he was young.

At first, that teacher was really supportive and impressed with how dedicated I was, but then he said something like “You’re not gonna get into a college jazz program, you shouldn’t even try.” Pretty unhelpful. [VS agrees.] I was accepted at NYU, the only school I auditioned for.

I eventually put together that I was only accepted because of my classical skills, and because they wanted more women in the department, which was pretty painful to realize. Embarrassing too.

If I’d looked around when I toured the school, maybe I would have noticed that women were lacking, but at the time, I just wasn’t thinking about it. The only women students were in the composition program, or singers.

There were no women instrumentalists the year before I got there, and then there were three or four of us the year that I got in. And they put us all in the same jazz ensemble— all the women in one group with this one bass player named Noah! It was terrible and I was embarrassed. It was a terrible experience, considering how invested and dedicated I was.

Then I failed my sophomore jury, and I was mortified. I mean, my playing definitely wasn’t quite there, but I was sincerely trying and coming along. There was something very cold about it. I didn’t know they failed me until that summer, after I had already signed up for next year’s classes in the jazz department.

I didn’t even tell my parents what happened, I told very few people actually. That changed me, and I stopped playing drumset.

Knowing lots of women who went to undergraduate and graduate school for jazz - both older and younger than me - they tell a similar story of what it was like being a woman in these jazz departments, and often a more harrowing one. But in the end, I think the whole thing framed me for the best.

VS: What a disappointing and, I imagine, infuriating, and probably disheartening experience that must have been. But it didn’t hold you back in the slightest— you’ve gone on to accomplish so much, and I’m inspired by your example. So what came next?

AA: After jazz school ended, I decided to focus on hand drums at a place called Djoniba Drum and Dance Center in Manhattan, where I started studying some West African rhythms and concepts. Eventually I told my parents “I’m gonna drop out of college unless you let me go to Ghana for a month and study at this random program I found online” [laughs]. It was 2001. Online was very new. They agreed to cover tuition if I paid for the flight. So I worked all summer and went to this workshop, I honestly can’t believe they let me go.

I feel cheesy talking about it, but the experience was formative. There was drumming, singing with drumming, traditional songs and dances that went with these rhythms, mostly Ghanian music we studied, from the Ga people, which is more south Ghana around Accra. There was less djembe in this region— djembe is more from West African countries like Senegal, although they do have some djembe in Ghana. They often used wooden barrel drums called kpanlogos, and there was other percussion that we studied too— gonkogwe bell pattern stuff, aslatua shakers. We had classes all day, and then at night we would go around and see music at weddings, parties, funerals, celebrations.

It was a small group of us studying— myself, a woman from South Africa, a woman from Australia, and a guy from Boston who was more like an academic ethnomusicologist. I felt very safe within that, much more than I ever had.

But Ghana was just a month, and then I went back to school in the fall. Socially I was kind of a loner in the jazz department the whole time. I was never friends with anyone in there. It felt very me against them. I was mostly friends with people in and around the music technology department at NYU. That’s where I met Sarah Register [guitarist/co-leader of Talk Normal].

VS: Did you and Sarah start playing together right away?

AA: No. We were just friends at first. And by the time I was a junior, Sarah was a full-time mastering engineer and wasn’t actively playing music yet. No one was really into the stuff I was into then, but Sarah would often and intently listen to the music I liked and played for her.

VS: Well, what about drumset? When did that come back?

AA: I didn’t play drumset again until I was maybe 22. A good friend pushed me back into it. Then through Craigslist, I found a guitarist named Ninni Morgia. We had a duo called death.pool. We were a sort of Harry Pussy— primarily Bill Orcutt and Adris Hoyos… do you know them, or at least Bill?

VS: I don’t!

AA: You would like his recent work… Anyway, we were a Harry Pussy meets US Maple mash-up. I learned a tremendous amount about music and playing drums with Ninni, and I started to use my voice for the first time. I just kind of started singing, more sort of sounds, inflections, and outbursts instead of lyrics.

Then I had a solo project called Glen Olden in 2005-ish— I liked the name because it felt like a gender fluid pseudonym. In this project I wrote and performed all the music myself. But I tried to do too much— I played drums, I played piano, I’d loop the piano, sing over it, play drums over it. A circus. It forced me to write on my own, and a few of those songs became Talk Normal songs.

Simultaneously, I was also playing in a band called Antonius Block, led by Jorge Parreira DoCouto who I met doing live sound in NYC. He was a very compelling guitarist who played in alternate tunings, gave unhinged live performances, and had an incredible ethos about him. I helped them record an album and then joined the band on drums.

I loved this band! The singer was this ice-cold Austrian woman, who sang just like that, Jorge was this wild guitarist, and I would play basic, hard drums.

Sarah Register eventually joined Antonius Block on guitar/bass, and shortly after, the singer got tinnitus and hyperacusis really bad, so Antonius Block ended and that’s when Sarah and I started Talk Normal. Jorge was a big influence on Talk Normal, we employed a lot of his ethos when we started.

VS: I love Talk Normal doing Son House’s “Grinnin’ In Your Face.” It’s a radical re-imagining, and you and Sarah are so committed.

AA: Yeah, at first we were really into early blues, especially those early women— there were these compilations that came out which featured people like Geeshie Wiley, Elvie Thomas and so on that we were into. The lyrics from those women were really dark and heavy, almost twisted. Sarah and I bonded over that, and Laurie Anderson too.

Talk Normal was full-on from the get go. Drums, guitar, double vocal duty, a lot of noise, pretty aggressive and confrontational, and all under the umbrella of art no-wave punk, I guess. For 6 years we were very busy. We did a tremendous amount of support tours, lots of shows. We practiced a lot, released two albums and one EP. I suppose we had “success.”

And a lot of that “success” really came from the support of Sonic Youth. We owe so much to them. It’s beautiful the degree to which they platformed so many underground artists.

VS: That’s nice to hear, sort of what it’s all about. Wrapping up, could you talk about Gold Dime?

AA: Gold Dime started as a solo project— for more independence as a songwriter and to be able to communicate more clearly with guitarists, I taught myself guitar, I play in a fairly unorthodox style— pretty rhythmic, alternative tunings, noisy. The project has become a collective experimental art rock band that I’ve led the last 8 years or so. I do the lion’s share of the songwriting, but there’s a lot of collaboration.

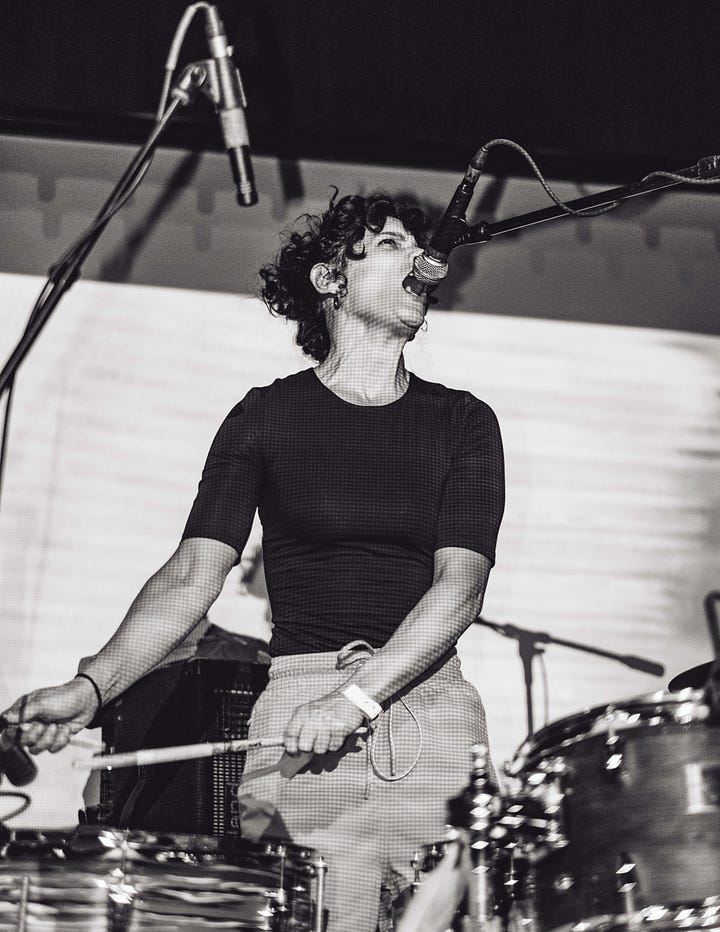

At our shows, I play drums and sing for the most part— I think of my voice as a fifth limb. This past year the live band has really gotten to a more powerful level with Matteo Liberatore (guitar) and Chris Mulligan (bass); I’m so thankful for their commitment. And it was a really excellent year being able to play so much with them at some pretty fun shows.

VS: I think what drew me to your music was your blending of styles and sounds— noise rock, literature, avant-garde jazz, something from African traditions, other things— in a very natural, un-showy way. And that seems to be sort of your musical history.

AA: Well, thank you! I guess I’m all over the place [laughs]... I mean, as you know, I came up listening to all sorts of musical genres but also in the 2000s, I do feel it was more common to witness different music in the same night, and at the same venue. I’m sure this helped frame how I create my own music as well as where I draw inspiration.

For instance at Tonic, where I ran sound, they’d have experimental art/noise rock bands, downtown jazz and then dance music in the basement, all in the same night. I really appreciated that. At the time, I didn’t really realize that that was perhaps a rare thing. Yes, those musical acts of varying genres weren’t necessarily on the same bill, but it made sense to me that they should all coexist together, and know and respect each other.

Today it feels like — jazz, experimental, art rock, noise, dark wave, ambient, dance genres, other— don’t mingle as much as they did then. I mean who knows, maybe I’m just not at the right shows. Should these observations be fact, it does bum me out.

VS: Yes, me too. Hence, this interview.

AA: Well then I’m glad we could attempt to blur the genre lines in our own tiny way! [laughs…]