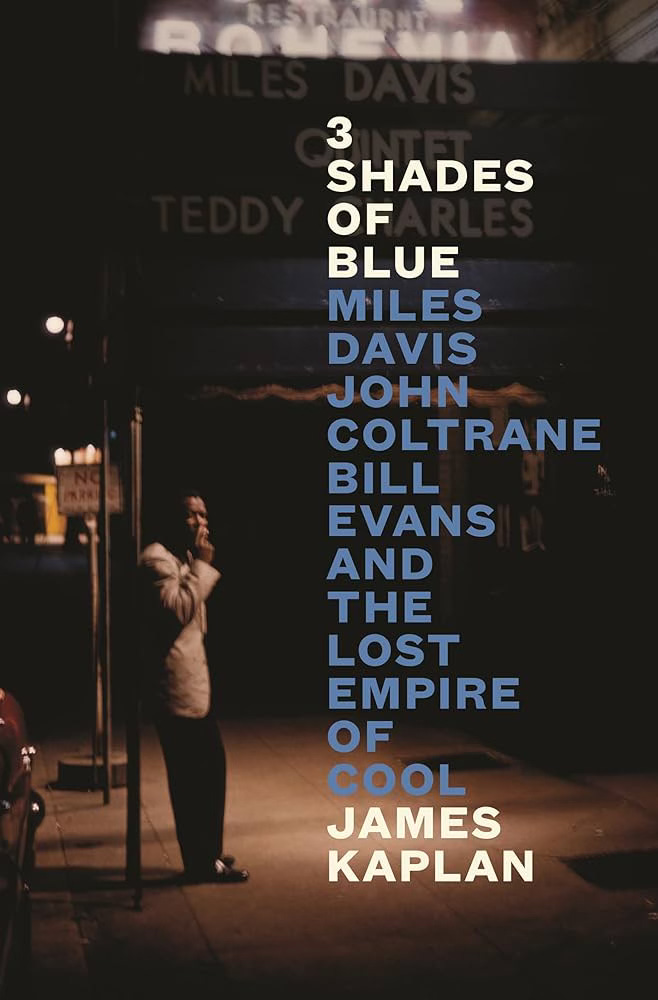

Once in a while, a literary star turns to jazz. James Kaplan came up through the rank-and-file at the New Yorker, spent time polishing scripts for Warner Brothers, and worked with Jerry Lewis and John McEnroe on their memoirs. He cracked the larger literary market with best-selling and possibly definitive biographies of Frank Sinatra and Irving Berlin; now, his newest book is 3 Shades Of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool.

3 Shades Of Blue has received extensive coverage and heaps of praise. (“A marvelous must-read for jazz fans and anyone interested in this dynamic period of American music” – Kirkus Review, etc.) It’s the #1 best-seller in jazz musician biographies on Amazon.

However, Kaplan neither gets nor likes most jazz. He likes a certain thing, his “empire of cool.” The lone dissenting review of this book seems to be by Peter Keepnews in the New York Times.

His three protagonists [Davis, Coltrane, Evans] played a vital role in bringing jazz to an artistic peak in the 1950s and ’60s. Then [according to Kaplan] things went south for the music, in terms of both its quality and the size of its audience, to the point that “jazz today, when it isn’t utterly ignored, is widely disliked.” For Kaplan, the genres known as bop and hard bop, which flourished in those years, provided “almost all of jazz that I want and need.”

In other words, the book is actually a subtle hatchet job on jazz by a tourist. The further I read, the more distressed I became.

There’s nothing easier than panning something. Indeed, I initially planned to only write about the endless examples of bravery and excellence across the musical spectrum, and simply ignore what I didn’t like. While I don’t wish to be unkind to a writer, nor to the hundreds of readers who enjoyed 3 Shades of Blue, it’s works of this sort that need full-throated, passionate criticism: showing what the work is and what it is not. For it is in 3 Shades of Blue’s dismissal of most jazz, while purporting to be a work about jazz, that James Kaplan goes wrong.

3 Shades of Blue is certainly, as Ted Gioia blurbed, a page-turner. Kaplan is a great writer, but in his narrative, the lives of Davis, Coltrane, and Evans only intertwine, resonate, or meaningfully connect when they’re in a band together. He finds no underlying patterns by which we can understand their lives, or new connections between them; the book is pretty much three compressed and intercut bios, trotting out all the well-known events, and centered around Kind of Blue. If 3 Shades of Blue were a jazz record, it would be mostly unaccompanied trumpet, unaccompanied saxophone, and unaccompanied piano, with a few quick duos and trios in the middle that we’ve all heard before.

When I first heard about 3 Shades of Blue, I was excited and thought “acclaimed biographer, subject with wide appeal— should be great”. I assumed it would be a fresh look at legendary musicians and not just another thing on Kind of Blue, which would be superfluous after Ashley Kahn’s lovely book about the album anyway.

I hoped we’d meet Miles Davis the accomplished trumpet player, intellectual, and professional musician instead of the media-savvy celebrity and symbol, or maybe get a new look at the musical connection between Coltrane and Miles.

As Lewis Porter has shown, the Miles-Coltrane association went all the way back to 1946, when Davis heard and liked Coltrane’s very first recordings, sides Coltrane cut when he was in the Navy. I assume these tracks were heard by no more than a dozen or so people in 1946— what were the chances that Miles Davis would be one of them?

To me, there’s a story here, or a chance to marvel at how tightly-knit the jazz world was in 1946. Kaplan, as gifted a writer as there’s ever been, could take a second to note the contribution of folks unknown to us; these lost (to us) names are the very fabric of the jazz community— they’re the folks in the club, the people who make the music possible. They deserve our attention and respect.

Kaplan, page 79:

Porter [Lewis Porter, jazz scholar, Coltrane specialist, fellow Substacker] writes that the letter [from drummer Joe Theimer who reports that ‘the Miles Davis’ was ‘knocked by Coltrane’s playing’] was dated October 29, 1946— which itself is amazing, in that anyone was already referring to the twenty year-old Miles, still in the midst of his apprentice years, as the Miles Davis. But even if the date is wrong, even if Dexter Culbertson [trumpet player who knew Miles and played the Coltrane recordings for him, described by Porter as a Davis protege from this period] was a only a bebop hanger-on rather than a protege, even if Miles was just being polite about Coltrane’s playing, a strange sort of connection— as Porter calls it “the connection that would eventually set Coltrane’s career in motion”— had been made.

Ouch! So much for attention and respect. In one paragraph, James Kaplan questions Porter’s scholarship, impugns the status of the barely-known Dexter Culbertson, and turns Miles Davis into a polite young man not wishing to offend, all while amazed that anyone would care about Miles Davis’s opinion in 1946.

There are some interviews. Kaplan talked to Wallace Roney, Dave Liebman, Richie Bierach, and Laurie Verchomin, Evans’s last girlfriend, and gets a comment or two from Jon Batiste. But as the book goes along, the voices of the musicians, especially Roney, feel more and more like afterthoughts.

Kaplan’s backgrounding of Wallace— a sorely-missed master jazz trumpeter and bandleader who was mentored by Miles from the early Eighties on— was hardest to accept. Wallace is one of the only Black voices interviewed by Kaplan for the book, but by the book’s middle, Roney is little more than a talking head, chiming in with a sentence or two to kinda-sorta confirm whatever Kaplan’s saying.

Kaplan never meaningfully explores Wallace’s statements, or searches for a deeper truth about Miles in Roney’s words. What a missed opportunity. Wallace Roney deserves better than this.

So we have a biographer at sea in the music to which his subjects were devoted; three rushed life stories, with little new research or interplay between the principals, beyond what’s widely known; under-utilized new interviews; and, most concerning, scores of inaccurate, confused, confusing, or banal statements about the music and musicians. That’s 3 Shades of Blue.

Sinatra and Berlin, with whom Kaplan made his reputation, are understood, if not as individuals, then as part of the American mythos. I mean, this week I’m in Nashville playing The Look of Love with Mark Morris, and the Sinatra Bar and Lounge, with an image of Ol’ Blue Eyes on the sign, is around the corner from my hotel, and Nashville— Music City, TN— is what it is because of songwriters and copyright.

Reading about Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans from someone who doesn’t command the terrain— someone who, by his own admission, has no need or want for jazz made after the Sixties— proves how far we need to go in basic understanding.

A few nights ago, after finishing a much longer draft of this essay, I needed jazz and community, so I went to Bar Bayeux to hear pianist Marc Copland, with John Hebert on bass, Robin Verheyen on tenor and soprano, and Anthony Pinciotti on drums. I’ve been going to hear Marc Copland since I was a teenager— what a special thing to be able to hear him now, sounding better than ever. The music was wonderful, fresh and intimate, it totally hit the spot. Marc Copland is a treasure.

The club filled up, and there were a few familiar faces in the audience, folks who know what I know: we’ve got it all. We have the music, and we have each other. I don’t know if we’re an empire of cool, but we’re a part of a special something much, much bigger than ourselves.

Jazz is beautiful, living stuff, a source of meaning that generates community, created by Black masters who gave their lives. It was a bummer to read a popular book by a brilliant and accomplished author that cannot acknowledge this basic fact, presenting the complex, still-evolving narratives of three of our nonpareils as tidy and settled things, a work that sees jazz in 2024 as a curiosity at best.

Special thanks to Ethan Iverson for help with this essay

Still don’t understand how anyone can write a book about Kind of Blue and not give Cannonball his due.

Sigh...Once again a book has been written that looks so, so, far back into the music called jazz.

I wonder if we will ever escape this seemingly endless need to focus on the long ago past.

I ask music students if they ever stopped to wonder why Charlie Parker ever moved past the playing of Sidney Bechet, or Prez. Do they wonder why Dizzy, Fats, or McGhee ever began to play the way they did, when Louis Armstrong had already made his great contributions? The same question could be asked of drummers, bassists, and just about any other instrumentalist throughout the evolution of jazz.

The icons so greatly appreciated from the 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s, were generally considered icons because they moved the music forward, and didn't freeze it, or look back to re-create the past.

There have been, and always will be, people who are more interested in the past than today or the future. That said, the things that made jazz/improvised music so vital, vibrant, alive, and creative, have seemingly been pushed aside, swept under the rug, or cast as some fringe idea that doesn't pay enough respect/attention to the past/nostalgia. Sadly, we will have mostly ignored the greatest contributions and contributors to the evolution of the music with a constant look backwards for what makes for great, creative minds, music, and voices that connect to the world we live in and that we have inhabited since the late 60s to today. If jazz and any other kind of music should be a reflection of our individual and collective lives, why do we ask young people to recreate ways of playing that have little to nothing to do with their world, culture, and experiences, that offers them little to no room for their own creative vision?

I'm not sure that every kind of music will continue to evolve forever. The blues seems to have run it's course. Rock music seems to mostly have run it's course. Classical music has new creative ideas, but they have been cast aside in favor of nostalgia, just like in the world of jazz.

I realize that this post is about a book I never even read, but I've read "this book" and books like it to many times.

To those who are involved in creative endeavors in the world of jazz, improvisation, New Music , etc...my only hope is that one day your creations will be given there proper due.

I've been accused of being anti-tradition. I am not anti-tradition. I have a great respect for the entire history of the music. I am however, very pro equal treatment and respect for the entirety of the idiom.

I believe it was Lester Bowie who said something akin to this...If we are going to talk about the history of jazz, we must include ALL OF THE HISTORY, up to and including today. We cannot cut it off at any point along the way. If we are going to talk about the importance of John Coltrane, we must hold his entire life and musical output equally important. This would include going all the way back to his earliest recordings around 1949, and ending at Expression.