Max Roach at 100: Part 2

Notes on Max's concepts and the earliest recorded bebop.

Lewis Porter graciously shared three choruses of a 1938 performance of “After You’ve Gone” played by tenor saxophonist Lester Young with Jo Jones on drums on his wonderful Substack. Follow this link and hear a few minutes of magic.

At the top of the second chorus, Jones switches from the hi hat to the ride cymbal. And there it is: state-of- the-art, ultra-modern jazz drumming. Played in an older style, sure, but don’t be fooled: nothing Jones does is easy to play, and his concept of interacting with the soloist is the exact concept I was using at my gig tonight with Ember.

Every drummer today, regardless of style or context, is playing a modern version of this.

Max Roach, one of the crucial artists of the 20th century, born 100 years ago this month, took Jo Jones’ concepts and made them his own. In Roach’s version, the right hand swings on the ride cymbal, the bass drum softly taps out quarter notes, the hi-hat claps on 2 and 4, and the left hand comments on the music as it unfolds with bits of clavè, polyrhythms, and shuffles.

Prior to Max, drummers only played like this sometimes: maybe at a jam session (the Lester Young and Jo Jones we just heard is from a jam session) or for a chorus behind a virtuosic horn solo in a big band. On the records Max made with Charlie Parker in the Forties—the original bebop recordings— Roach played like this all the time. In his hands, it was high art, and all followed in his wake.

Bebop, as a set of ideas— an emphasis on individuality, expectation of a unique technical accomplishment, an awareness of music around the world, and probably some others— is central to jazz’s identity. As a sound, it keeps changing; its meaning refuses to be fixed, frozen, or settled. Like all great music, bebop can speak to anybody, anytime.

I’m currently on the quixotic mission of learning to play a few Charlie Parker solos on the piano, and I walk around the city listening over and over to “Now’s The Time” from 1945, “Yardbird Suite” from 1946, and “Scrapple From The Apple” from 1948, quietly humming along at half-speed via the Amazing Slow Downer.

And the solos keep changing, always hitting me differently. Sometimes Charlie Parkers sounds like a militant revolutionary, anarchic and impatient, other times the solos seem romantic, wistful, and folk-like, or they sound experimental and argumentative, a researcher showing the results of experiments.

The same solos, over and over, different every time: this is why I love jazz.

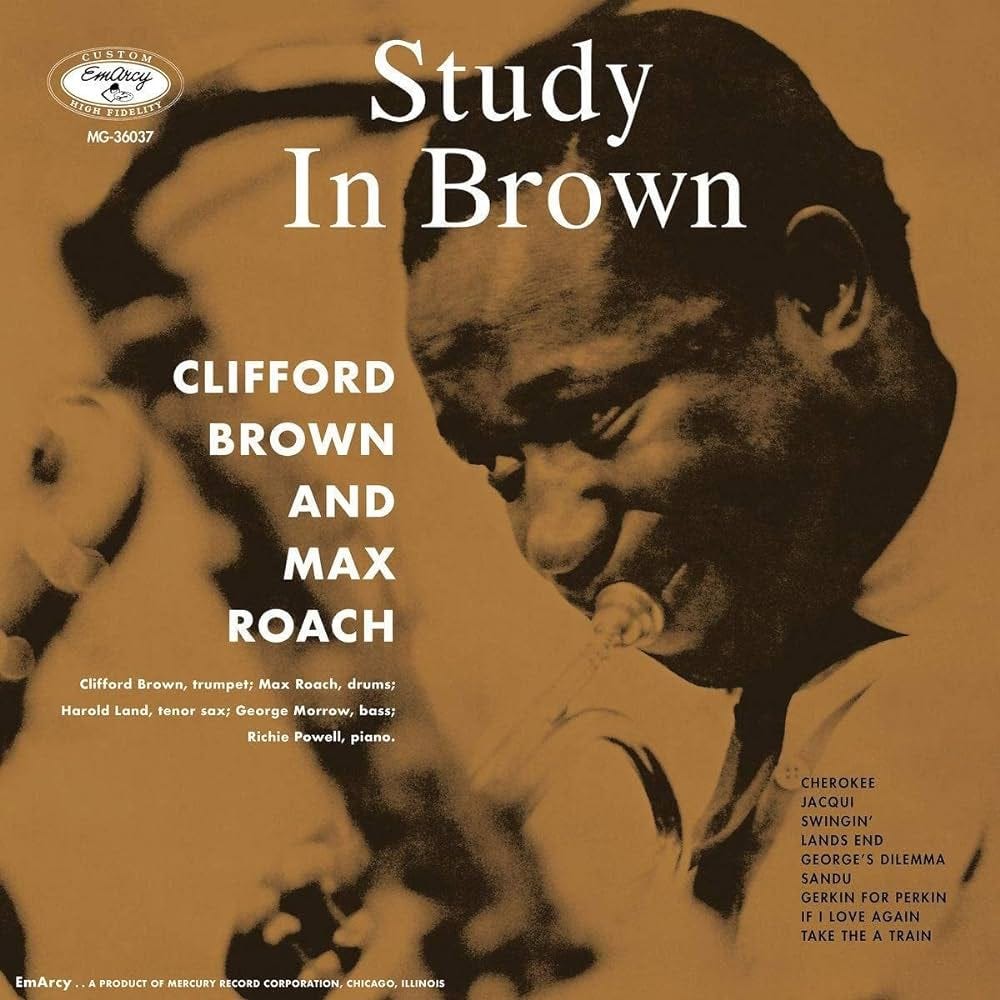

There’s Max Roach the cultural innovator, Civil Rights activist, and experimental pan-African jazz musician. There’s also Max Roach the jazz drummer. Nate Chinen, in his beautiful piece about Roach, writes lovingly about Max playing “Cherokee” with Clifford Brown; like Chinen, sometimes when I hear this track, all I can hear is Max’s right hand on the ride cymbal.

When asked about his mastery of rapid tempos, Roach would reply that it was a matter of staying relaxed, and letting the tempo take care of itself. Indeed, there’s something of the championship boxer or the chess master on “Cherokee”, as Roach refuses to go all in until absolutely necessary. His solo is a knockout punch— one chorus, 64 rapid bars that meticulously parallel and outline the form of the tune. This is devastating: after playing cool and flowing for four minutes, he ends the match.

On “Cherokee”, Roach is playing single strokes, but as precise and clear as his ideas are, he’s relaxed about his articulation. His loose left hand puts some extra rattle in there, giving his phrases a hint of mystery, folkways, and African perspective. Max is a virtuoso of design and architecture, and this solo on “Cherokee” is a new standard: an improvised composition. At the same time, this is some of the most exciting, swinging music ever waxed: the jazz dichotomy dual bell is rung again.

The iconic Max Roach drum sound is featured on Study In Brown: high, hissing cymbals are front and center, with snare and toms tuned way up, evoking bongos and timbales. The overall effect emphasizes treble, allowing Max’s sound and ideas to sing out over the band; with this tuning and these cymbals, everything Roach plays will be heard.

But “Cherokee” was recorded in 1955, eleven years after Max first began making records, and almost ten years after Charlie Parker’s “Ko Ko”, a legendary Roach performance. That classic, ‘treble Max’ sound isn’t present on “Ko-Ko”, nor on any of the canonical bebop records he was making at the time. The treble Max sound was something he arrived at.

The earliest example of treble Max I know is the Thelonious Monk session for Prestige in December 1952, which yielded the original “Trinkle Tinkle”. It’s also heard on the Charlie Parker Verve session later that month which gave us “The Song Is You”.

A brand-new Gretsch drumset is part of the story— the drumset Max is playing at the Three Deuces with Charlie Parker and Miles Davis simply couldn't be tuned to the treble range that Max was now exploring. But what came first, Max’s search for more clarity or a new, precision-engineered Gretsch kit?

All drummers buy new drumsets, few create a new sound and vocabulary with them.

Ultimately, these questions— what makes bebop drumming different from swing drumming? how, when, and why did Roach teach himself to take a drum solo on the form of the tune? when did Max’s characteristic sound first appear? — lead back to my haziness about the earliest bebop. Perhaps if we hear Max Roach and bebop from the beginning, maybe we could enjoy it and understand it more.

I remind myself that this is music— a human activity— and therefore a final, complete, and correct understanding is not possible. Nor, really, is it even desired. If we knew what the music meant, perfectly and completely, why would we listen to it?

I’m going to pretend to be an astute and rather obsessive jazz fan in the late Forties in NYC. I spend all my money and time hitting the clubs and building up my home record library, with a special interest in Max Roach.

Listed below is what I would have bought. These are all the bebop records featuring Max Roach with Dizzy Gillespie and/or Charlie Parker that were recorded and released in 1944 and 1945.

For my own understanding, I made a YouTube playlist with every song, in chronological order of release, following the original A and B side designations.

Coleman Hawkins w/ Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach, February 1944: “The First Bebop Session”.

Apollo Records 751: “Woody’N You” (Gillespie)/ “Rainbow Mist” (Hawkins). On the original “Woody’N You”, Roach goes to a fuzzy Chinese cymbal behind Hawkins, and rides his hi-hats behind Gillespie. Bassist Oscar Pettiford stands out, playing gorgeous melodies right at the top.

Apollo Records 752: “Bu-dee-daht” (Budd Johnson and Clyde Hart)/ “Yesterdays” (Jerome Kern). Roach, just 20 years old, is aggressive behind Gillespie, and a distinct swing stylist: check out the 4-bar solo he has at the end of “Bu-dee-daht” to hear Max playing pure Swing Era drums.

Apollo Records 753: “Disorder at the Border” (Hawkins)/ “Feeling Zero” (Hawkins). Roach is heavy and swinging on “Border”, almost in Louis Jordan territory; it’s hard to imagine that in less than two years he would be the experimental innovator with Charlie Parker.

Sarah Vaughan with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Max Roach, May 1945:

Continental 6008: “What More Can A Woman Do” (Peggy Lee-Dave Barbour)/ “I’d Rather Have A Memory Than A Dream” (Leonard Feather-Jessyca Russell). Sarah Vaughan is important, an accomplished pianist as well as a definitive vocalist with deep connections to the beboppers. No Roach revelations here, but the romantic and urbane ballad was a crucial part of the beboppers’ repertoire, good to hear these examples of the form.

Continental 6024: “Mean To Me” (Roy E. Turk-Fred Alhert)/ “Signing Off” (Leonard Feather-Jessyca Russell). The revolutionaries are at the gate! Bird’s entrance on “Mean To Me” is breathtaking, Vaughan is subtly reimagining the tune, and Roach subdivides the triplet behind Flip Phillips at the end of his first A. “Signing Off” is from a different session, without Dizzy, Bird, or Max. I’ve included it for context, a chance to hear how truly different Vaughan, Gillespie, Bird, and Max were.

I might have gone to this concert:

Charlie Parker & Dizzy Gillespie at Town Hall, June 22, 1945. Here’s a separate YouTube link for this concert, which really deserves its own essay. This is Roach the revolutionary, a full bebopper now, no longer a swing apprentice. It’s fascinating to compare Roach to Sid Catlett, Roach’s senior by fourteen years, who replaces Max on “Hot House” and “52nd Street Theme”. Catlett fits right in with youngsters, and gets his own sound on Max’s drums.

Maybe I would have heard through the grapevine about this recording session:

Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Sadik Hakim, Curley Russell, Max Roach, NYC, Nov 26, 1945.

Which yielded these Savoy releases, some of which came out years later:

Savoy 573: “Billie’s Bounce” (Parker)/ “Now’s The Time” (Parker). Roach answers every Parker phrase, supports and challenges the young Miles Davis, and creates the paradigm of the modern progressive jazz drummer. The tiny difference in tempos between “Billie’s Bounce” and “Now’s The Time” give them very different feelings.

Savoy 597: Don Byas: “How High The Moon” (Hamilton-Lewis)/ Charlie Parker: “Ko Ko” (Parker). Roach is not on “How High The Moon”— that’s the excellent Fred Radcliffe, of whom I’d never heard before I started this essay. Radcliffe, a great player, is slightly more conservative than Roach, while Max sets the template for the future on “Ko Ko”.

Savoy 903: Stan Getz: “Opus De Bop”(Hank Jones) /Charlie Parker: “Thriving From A Riff” a.k.a. “Anthropology” (Parker). I’d never heard Getz’ “Opus De Bop” before, a great Max track with interesting details, including the hi-hat intro and two brief solos, while Roach’s beat on “Anthropology” is flexible and driving. This pairing of a Getz cut and a Bird tune on one 78 shows that, though not yet 25 years old and working in a new idiom, Roach tailors his playing to fit the situation.

Savoy 945: Charlie Parker: “Warming Up A Riff” (Parker)/ Leo Parker: “Wee-Dot” (J.J. Johnson). “Warming Up A Riff” is a medium-up “Cherokee”, and Roach is flowing and chatty. “Wee-Dot” is from 1947, with Shadow Wilson on drums, swinging so hard that it starts to feel like rock and roll.

COMING SOON: Max Roach Centenary Post part 3: The Max Roach Duos.

What's so exciting about your essays is how we get to learn alongside you plus how you teach us to listen. Many years ago, I received "The Complete Clifford Brown on Emarcy" (great music, lousy packaging) and reveled in the work that Brownie and Mr. Roach created (along with a dynamic band). Now, I want to go back and listen with fresh ears!

treble max, lol... hey you are really into this!! kudos on your willingness to share it all too!