On Backbeats

Ten tracks by five master backbeat drummers, inspired by Ethan Iverson's Rolling Stones/Steve Jordan article.

As with anything essential, getting a backbeat right becomes an advanced topic. In the 20th century, African Americans created the template.

Along with giving due credit to Earl Palmer, [drummer Steve] Jordan named more of the beat’s greatest proponents: Al Jackson Jr. of the Stax Records house band and Al Green’s band at Hi Records; Benny Benjamin, of Motown’s house band, informally known as the Funk Brothers; Fred Below, who accompanied Chess Records artists like Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley; and James Brown drummers Clyde Stubblefield and John “Jabo” Starks, whose beats reverberate through hip-hop in the form of samples.

—Ethan Iverson, “In Search Of The Backbeat”, The Nation, August 2024

If you haven’t read Ethan Iverson’s wonderful article on The Rolling Stones, Steve Jordan, and the development of the backbeat, here it is.

Joining a group of longtime friends at a Stones concert earlier this year, Iverson meditates on the development of the backbeat, the organizing principle of all R&B, rock and roll, and similarly-derived music, roping in observations about Steve Jordan, the Stones’ cultural history, and the value of big-tent music. I’ve read a lot of writing on these subjects, and Iverson’s stands out as some of the best. Bravo Ethan!

For me, the heart of the piece is how Iverson finds the whole experience of the Stones, Steve Jordan, and the backbeat intimately connected to everything he cares about as a musician, composer, and critic. But maybe I’m biased, because that’s how I am— I love rock drummers, and I love all the classic rock drummers, the English guys in those British bands: Charlie Watts, Keith Moon, John Bonham, Ringo, Bill Bruford, Ginger Baker, and on and on. I hear them as part of the wider story of African American jazz drumming and American music.

One thing I notice now is how different they sound from each other— the range of tuning and touch from, say, Charlie Watts to John Bonham is astonishing, considering they weren’t so far apart in age (Watts was born in 1941, Bonham in 1948) and were working in the same field. Really, the only thing they have in common is their individuality— each was a unique stylist with personal and idiosyncratic approaches to the African American tradition. Perhaps they were more-or-less amateurs when they became famous, but they all matured and made real contributions.

More than that, those players had the juice— when they were at their best, they pointed to a much wider world of music. Like most folks my age, it was rock music that led me to jazz, and it seemed a natural, unremarkable progression, just a walk across a bridge.

Most valuably, Iverson’s article is basic musicology, showing how the backbeat is a distillation of complex African diaspora traditions. Steve Jordan names some of the primary architects of the backbeat— what a thrill to read the names of Benny Benjamin, Fred Below, Al Jackson Jr., Clyde Stubblefield, and John “Jabo” Starks on the august pages of The Nation.

Jordan’s list is perfect— lots of other folks sounded great and pushed the backbeat along, but these are the foundational players, the shortest possible list. It spurred me to revisit some tracks, check some dates, look at Discogs, Modern Drummer, Wikipedia, books, and liner notes, brushing up on who played on what song. I wanted to arrange these drummers chronologically, to see if we could hear the backbeat emerge, morph, and deepen. You can click on each song individually, or check out this playlist.

New Orleans native Earl Palmer is one of the primary creators of rock and roll, but his background was in jazz, citing a Billy Eckstine concert with Art Blakey on drums as a foundational moment. Eventually, Palmer became a Los Angeles studio drummer, playing on some of Phil Spector’s hits and countless movie and TV soundtracks, as well as serving as a longtime officer of the Los Angeles musician’s union.

Earl Palmer with Lloyd Price, “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” (Price), recorded March 1952 in New Orleans, LA for Specialty Records. Fats Domino is playing piano, but the track is defined by Earl Palmer’s backbeat. Rock and roll would eventually be a push-pull between straight eighth notes and swung eighth notes, but in 1952, Palmer’s authoritative 12/8 was the whole story.

Earl Palmer with Professor Longhair, “In The Night” (Henry Byrd), recorded November 1953 in New Orleans, LA for Atlantic Records. On the previous track, the backbeat is obviously African American, but here, Palmer shows the backbeat’s roots in Afro-Cuban traditions. His continuous 2+/4+ evoke a conga pattern, while Longhair (Henry Byrd)’s piano and the sax section lightly hint at habanero.

The story of gospel, blues, R&B, and rock and roll— what Peter Guralnick calls “American vernacular music”— is in part the story of the independent record labels. It’s also, in part, the story of innovative drummers, folks who created the template for all modern backbeat drumming. Not surprisingly, all of these gentlemen shared a jazz background.

Connie Kay, famously of the Modern Jazz Quartet, was gainfully employed by Atlantic Records as a rhythm and blues drummer prior to joining the quartet.

Benny Benjamin, born in Alabama in July 1925, and Fred Below, born in September 1926, were the drummers most associated with Motown Records and Chess Records, respectively, while Al Jackson Jr, born in 1935 (the same year as Albert “Tootie” Heath) was most associated with Memphis-based Stax Records.

I could find little concrete new info about Benjamin, a Birmingham, AL native, but, as with he and Al Jackson Jr., we can hear their deep jazz background plain as day.

Fred Below first studied under Captain Walter Dyett at DuSable High School in Chicago (he was classmates with tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin, among others). After World War II, he enrolled at the Roy Knapp School of Percussion, an accredited music school where he received composition and music history classes in addition to drumset lessons. Like Earl Palmer, Fred Below was all about Billy Eckstine with Art Blakey. But he was attracted to blues, R&B, and rock and roll in part because he knew nothing about it:

Here's a funny thing. I thought I knew enough about music that I was able to play anything. But, here was a type of music [Chicago blues] I'd never heard of ! Man, it was really something that I wanted to get to. I said to myself, "Wow! Here's something that I can't play and I think I know music! I'd better learn this."

-Fred Below, Modern Drummer, September 1983

Fred Below with Little Walter, “My Babe” (Wille Dixon), recorded February 1955 in Chicago, IL for Chess Records. Charlie Parker was still alive when Below tapped out this spare, elegant, and low-volume backbeat with brushes on a calfskin head. Using only a snare and bass drum, Below’s simple backbeat ties together gospel, swing, and Little Walter’s swagger, finding a meeting place of country wisdom and urban sophistication.

Benny Benjamin with Barrett Strong, “Money (That’s What I Want)” (Berry Gordy), recorded 1959 in Detroit, MI for Tamla-Motown Records. This was the first Motown hit, and Benny Benjamin’s elemental eighth notes on the floor tom are as much a part of the song as the vocal and piano. When Benjamin opens up into the Latin beat, the Swingin’ Sixties come into view.

Fred Below with Chuck Berry: “Let It Rock” (Berry), recorded 1960 in Chicago, IL for Chess Records. Recording technology now lets us savor the drummer’s details. Check out Below’s shuffling left hand on the snare drum, spang-a-lang on the ride cymbal, and syncopated bass drum; he’s the train that Berry singing about. This is a ferocious performance, perfectly matched to Berry’s vocal and the song’s subject matter. Incredible to realize “Let It Rock” was recorded after Kind of Blue and Giant Steps.

Al Jackson Jr. with Booker T. and The MGs, “Green Onions” (Jones-Cropper-Jackson-Steinberg), recorded 1962 in Memphis, TN for Stax Records. A distillation of the Jimmy Smith/Blue Note sound into three minutes of timeless cool, Jackson’s elemental beat is slick, clean, and perfectly in time. No fills, no variations, just subtle dynamics and intense focus.

Benny Benjamin with Stevie Wonder, “Uptight” (Stevie Wonder, Henry Cosby, Sylvia Moy), recorded 1965 in Detroit, MI for Tamla-Motown. Six years after “Money”, Benjamin plays the ur-Motown beat, the basic template used on dozens of hit records: eighth notes on the hi-hat, four stomping quarter notes on the snare, and a bass drum in conversation with James Jamerson’s bass lines. Benny’s sound is exuberant— the drums are open, un-muffled and ringing, with a noticeably long note on the bass drum. Benjamin’s connection to Wonder’s vocal is what singer drumming is all about. Songwriter Brian Holland (of Holland-Dozier-Holland) said Benjamin was always into the music he was recording, singing along, putting himself into the music. That’s easy to hear on this track.

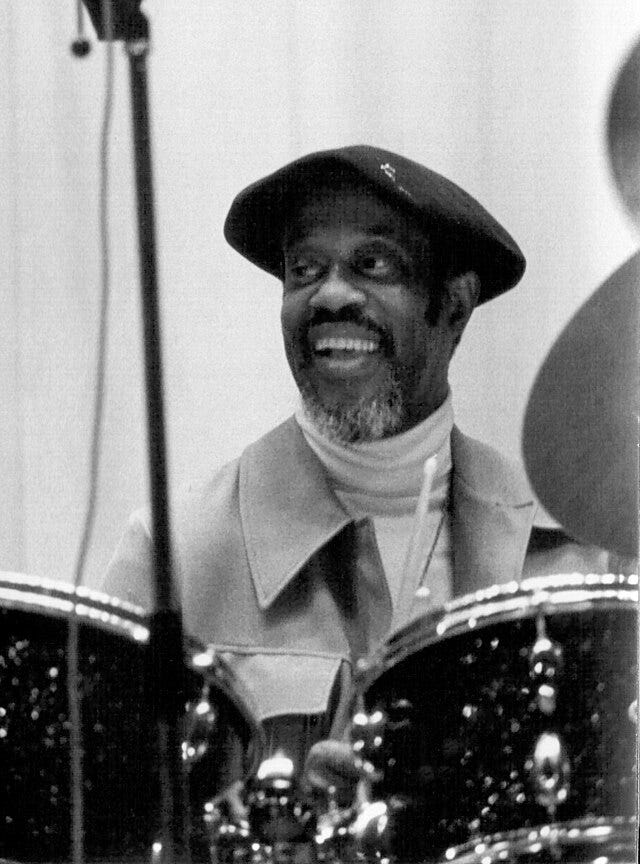

James Brown had been on the charts since “Please Please Please” in 1956. In the late Sixties, he slowly and methodically reinvented his music, with the drums becoming the focal point of his sound. Clyde Stubblefield, born in 1943 (the same year as Al Foster and Freddie Waits) and John “Jabo” Starks, born in 1937 (the same year as Louis Hayes and Horacee Arnold) were the two drummers around whom Brown built his new style.

Clyde Stubblefield with James Brown, “Cold Sweat” (James Brown-Alfred “Pee Wee” Ellis), recorded 1967 in Cincinnati, OH for King Records. Stubblefield’s syncopated and melodic pattern first displaces the backbeat, then brings it back, a hypnotic two-bar hide-and-seek that enchants and delights. Brown and Stubblefield’s innovations were so unlike anything else in 1967 that they eventually gave rise to a new subgenre of R&B, known usually as funk.

John “Jabo” Starks with James Brown, “Soul Power” (James Brown), recorded 1971 in Cincinnati, OH for King Records. Starks finds the swing in the 16th notes, a subtle shuffle in his left hand’s grace notes that gives “Soul Power” a feel that’s both relaxed and intense. Stubblefield and Starks tuned their snares high, tight, and dry, and kept their bass drums dry and thuddy, the template for backbeat music to this day. Also, the way the snare drum rings indicates that Starks and the band are playing at a lower volume than I would have guessed.

Al Jackson Jr. with Al Green, “Let’s Stay Together” (Al Green-Willie Mitchell-Al Jackson), recorded 1972 in Memphis, TN for Hi Records. Twenty years after “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” and Earl Palmer, the backbeat is now as much a part of the song as the melody and harmony. On the verses, Jackson’s left hand plays the backbeat on the snare as usual, but his right hand travels from the hi-hat to a muffled floor tom to play the backbeat in unison with the snare, softening the backbeat, adding to the almost painful intimacy of Green’s signature song.

Nice piece, Vinnie (although I don't share your veneration of my British compatriots).

One American session drummer you might have mentioned is Al Duncan, who played on many important Chess and VeeJay records in Chicago in the late 50s/early 60s, notably the Impressions' and Major Lance's early hits, on which his feel and tom-tom fills were very distinctive.

Also a couple of other Detroit drummers were used on many Motown hits, particularly after Benny Benjamin became unreliable: Richard "Pistol" Allen and Uriel Jones, both wonderful players. Did you know that the drummer on Martha & the Vandellas' "Dancing in the Street", an ur-Motown track, was the great Freddie Waits, a hard bop master (and father of Nasheet)? In the 60s, producers, musicians and fans spent much time trying to figure out the ingredients of the Motown backbeat. Eventually it became clear that it was a combination of snare, Jack Ashford's tambourine, and a chopped guitar chord played sometimes by Eddie Willis but usually Joe Messina, who used a Telecaster with heavy-guage strings for the job. Carefully balanced, that gave the Motown backbeat its unique colour and resonance. And, of course, the acoustics of the Snake Pit, Studio A at Hitsville USA, 2648 West Grand Blvd.

I wrote about Al Duncan on my blog a few years ago:

https://thebluemoment.com/2018/03/23/the-story-of-al-duncan/

A while later this excellent interview turned up:

https://scottkfish.com/2016/01/09/al-duncan-big-ears-and-a-good-memory/

All best, Richard

Growing listening to Black music distilled by English drummers, one can not argue at all with Steve Jordan's list of the great foundational drummers. I'd add Ziggy Modeliste from The Meters to any list of "funky" drummers (I mean, "Cissy Strut" is downright "filthy funk"!). Thanks, Vinnie!