Phil Freeman of Burning Ambulance, fellow Substacker and veteran music writer with three books under his name— New York is Now!: The New Wave of Free Jazz (2001), Running the Voodoo Down: The Electric Music of Miles Davis (2005), and Ugly Beauty: Jazz in the 21st Century (2022)— has a new one out this month, a full-length study of pianist/composer Cecil Taylor.

Beautiful titled In The Brewing Luminous: The Life And Music of Cecil Taylor, Freeman’s latest book is just great. In Phil’s clear, unfussy prose, we get a straightforward account of Taylor’s life, with Cecil and a chorus of his collaborators quoted at length for depth and context. But a significant portion of In The Brewing Luminous, however, is an overview of Cecil’s discography; Freeman listened to, and comments briefly on, each and every officially-released Cecil Taylor recording.

Give it up to Phil Freeman for digesting the entirety of Cecil’s huge recorded legacy! This dedication, plus his thorough research and natural affinity with Taylor’s music, makes In The Brewing Luminous an essential resource for anyone interested in Cecil Taylor.

Did Freeman write his book to get us listening to Cecil? If so, it worked on me— by page 100, I had an entirely new sense of Taylor’s music and the man behind it. While continuing to read, I put on Unit Structures (Blue Note, 1966) and enjoyed it in a way I never had.

After meeting Taylor’s parents and cousins in the book’s first chapter, the rest of the text gives us only glimpses of Cecil’s personal life, for In The Brewing Luminous is laser-focussed on Taylor’s public life. As Freeman closely tracks Cecil’s concerts, residencies, recording sessions, and album releases, year after year, always dropping in a helpful quote from Taylor or an eyewitness, somehow the general vibe and idea of Cecil and his music just emerges, similar to how one could get a sense of Sonny Rollins in Aidan Levy’s masterful biography without Levy pausing to describe Sonny’s personality.

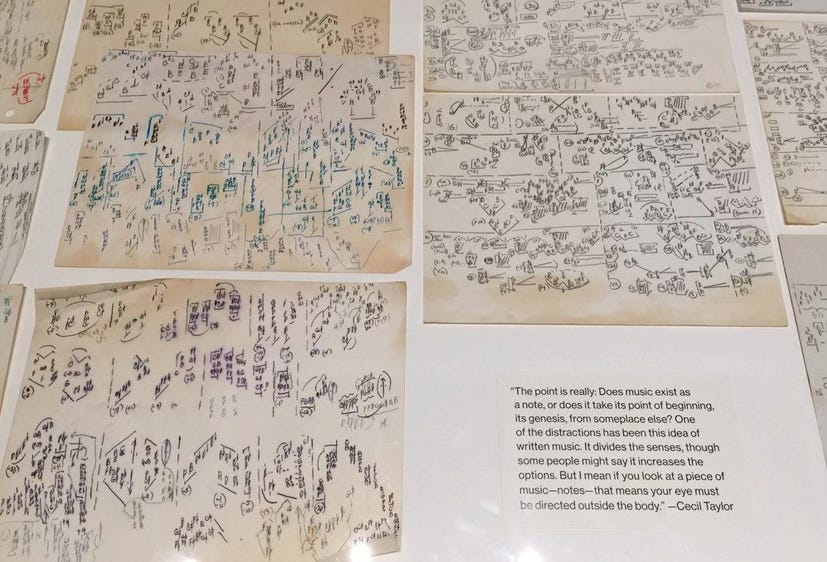

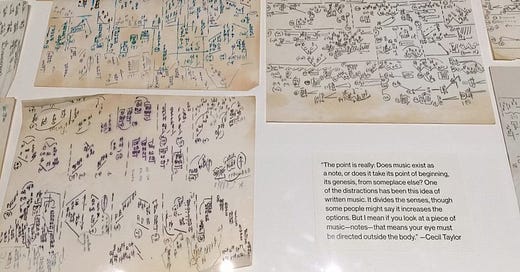

At the Whitney’s Cecil Taylor: Open Plan, an exhibit in 2016 where Taylor gave his final public performance, several of his scores were displayed— stacks of notes written out by letter climbing up and down the page. “Do the musicians actually play these?” I wondered; Freeman listened to all the music, and he can say for certain that yes, sometimes they did. Several multi-volume live releases feature, according to Freeman, the same compositions in back-to-back concerts, though the titles might say otherwise.

Indeed, a constant through Cecil’s career was his evolving views on notated music. Freeman shows how he, like Ornette Coleman, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, and many others, came to feel that notated music was, at best, a compromise, and at worst, a system that robbed music of its power.

From In The Brewing Luminous:

While rehearsing for the Whitney performance [in the Nineties, not the 2016 one I mentioned above] which consisted of a new work called “Ila Ila Tado” that included chanting, Taylor gave a fascinating interview to Gary Giddins for the Village Voice, which was later incorporated into his book Riding On a Blue Note.

In it, Taylor discussed his investigations into African culture and how they had impacted his music, and his life. He pointed out that “the non-European aspects of the music” were inaudible to white scholars and some listeners, due to the imposition of “a non-historical continuum” thanks to the fracturing of African cultural traditions through slavery, and the resulting ignorance of “the continuance of methodological procedures” from Africa, including oral transmission and shaping of the music through collective rehearsal.

Instead, “a conception of ordered music which is retained through symbols” was prioritized.

In The Brewing Luminous showed me how Taylor’s music, which, when I first heard it, seemed sort of intimidating and extreme, was a natural extension of the glamorous Cecil Taylor I occasionally spotted hanging out at jazz clubs (anyone hanging around the Village twenty years ago would have seen Taylor once or twice). The few times I saw him, Cecil was a celebrity, soaking up the attention, sometimes even dancing a little, putting on a show for us. This was Cecil Taylor?

Freeman and William Parker:

Taylor seems to have taken little interest in the loft scene — he occasionally turned up in the audience, but he never performed officially at Studio Rivbea, the Ladies Fort, or any of the other non-professional/residential spaces that cropped up in those years.

As William Parker explained, “Cecil had no interest in playing in the lofts...He loved playing in clubs. Because that’s where he went to hear music. You know, he always told the stories about how he went to see Billie Holiday and Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk in clubs, so he loved playing in clubs. It wasn’t like he was trying to be only [in] Carnegie Hall or big halls.”

Jazz clubs, dance clubs, a private booth at the KGB bar, all-night gatherings of the sophisticated and attractive, with Champagne and sorbet, memories of Ellington, Monk, and his parents, a personal system for notation….I started to get it.

Until I read Freeman’s book, I was totally deaf to the urbanity in Cecil. Perhaps it’s this quality, the nighttime New York City-ness of Cecil, which ties his music to Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington, more than any specific musicological connection.

At the end, I was most grateful for the overall vibe of In The Brewing Luminous: patient and low-key words about a man for whom nothing was low-key. But Phil’s unhurried tone and simple descriptions never diminish Taylor’s music, don’t wave away Cecil’s fundamental complexity and irreducibility. For me, it was just the opposite; it inspired me to dive in and wrestle with Cecil’s music anew.

Freeman’s book is aspirational in introducing us to every record Taylor made, but realistic about the idea of ever fully ‘getting’ Cecil. Without saying so, In The Brewing Luminous suggests that instead of trying to understand Cecil Taylor, maybe we should just listen.

As Freeman writes, “Cecil Taylor is gone. He will never make any more of this tremendous, sweeping music. Now, at last, we have time to absorb it.”

Bravo Phil! Respect and gratitude for Cecil Taylor.

Bonus Tracks: Cecil and the Drummers

“Air” (Cecil Taylor), from The World Of Cecil Taylor (Candid, 1960); Denis Charles, drums. With his pure Afro-Cuban opening, some wild chattering eighth notes in the left hand, and a driving time feel very close to Ed Blackwell’s, “Air” shows how much Denis Charles belongs among Blackwell and Higgins for showing how the Kenny Clarke/Max Roach bebop paradigm could be subtly tweaked to enable the coming New Thing.

“Bulbs” (Cecil Taylor), from Into The Hot (Impulse, 1961); Sunny Murray, drums. On Murray’s second-ever recording session, he navigates Taylor’s rapidly-evolving compositional style with ease; I admire how smoothly Murray and the band change tempos. This track proves that Murray certainly could play more-or-less conventional jazz drums.

“Conquistador” (Cecil Taylor), from Conquistador! (Blue Note, 1968); Andrew Cyrille, drums. Cyrille could be as driving as Denis Charles or as loose and wave-like as Murray, making him the ideal drummer for Cecil in this period. Did Andrew’s training in classical percussion give him the control on display here? Notice how he blends precisely with the ensemble, how every note is given a precise envelope of attack and decay. A great performance from one of our living masters.

“Morgan’s Motian” (Cecil Taylor), from Tony Williams: The Joy of Flying (Columbia, 1979); Tony Williams, drums. Amiri Baraka praised the Tony-Cecil hookup after seeing them play together in the mid-Sixties, but so far, this lone track is the only document we have of their chemistry. Williams is as nimble as Cyrille, and the nuances and details of Williams’ big sound are beautifully captured by engineer Stan Tonkel.

“Epicritic (Pertaining to Cutaneous Sensitivity)” from Cecil Taylor Feel Trio: 2 T’s For A Lovely T (Codanza, recorded 1990). Here’s Tony Oxley’s ‘European’ sensibility: an expanded sonic palette and commitment to sound sculpture. With bassist William Parker, the Feel Trio was unstoppable; this must be some of the most relentless, kinetic music ever made.

Thank you so much for heightening my excitement about reading the book. Cecil was a marvel and I agree that one can convey his essence simply and elegantly without losing anything. This was in fact my sense of Cecil from my one extended personal conversation with him, however much I felt in awe of him.