The R&B Roots of Modern Jazz

Fifties R&B records with Jimmy Cobb, Philly Joe Jones, Art Blakey, and Elvin Jones.

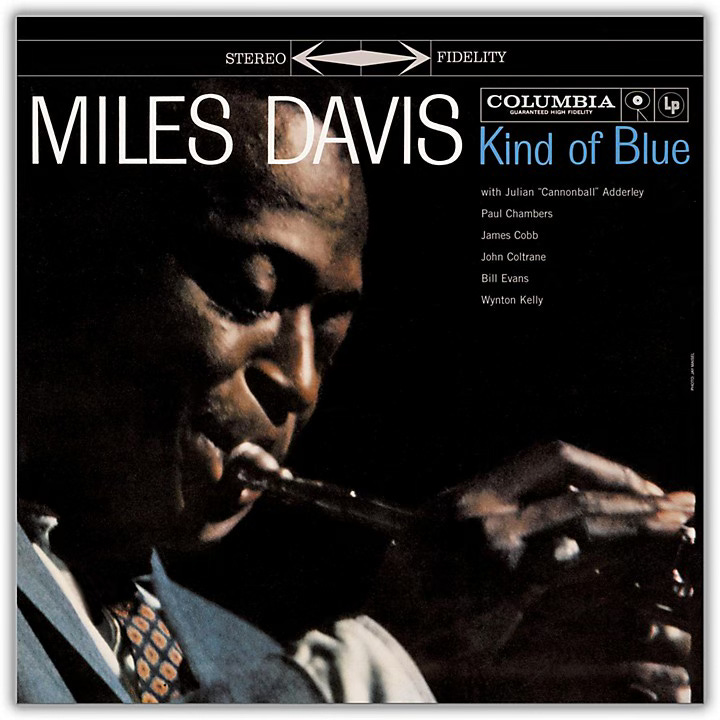

Jimmy Cobb is the drummer on Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz record of all time. Cobb, who died in 2020, was a regular presence in NYC clubs up until his passing, heard often with guitarist Peter Bernstein. My peer group and I heard him regularly, a great privilege.

One night stands out: Village Vanguard, spring 2012— Peter Bernstein, pianist Harold Mabern, bassist John Webber, and Cobb. On a second set, Jimmy turned it on: the atmosphere was charged, the excitement was palpable, and it was all there— the beat and cymbal sound we know from Miles’ records, fire and energy, even some round-the-toms chops on a low-tuned five-piece kit. This is the glimpse of Jimmy Cobb’s artistry that stays with me.

Cobb’s contribution to Kind of Blue is essential, one of the great recorded performances in jazz. Though he’s the least showcased player on the album— Paul Chambers is given ample solo space by comparison— it’s Cobb’s subtle drive and quiet engagement that guides us through the tunes; his minute adjustments accommodate the soloists. Cobb is the glue that holds the music together.

What Jimmy is doing on the record might sound simple or easy, but it isn’t. In fact, it’s a huge technical and conceptual challenge to play the way he does. As Miles Davis, Bill Evans, Cannonball, and John Coltrane colloquy from on high, Jimmy Cobb keeps us dancing. This is hard to do.

3/4 and 6/8 were the new rhythms in the air. Elvin Jones was the only drummer that could make “My Favorite Things” what it was; likewise, Jimmy Cobb was the only drummer that could play “All Blues”. A fitting situation, since Jimmy Cobb started his professional life in NYC as a rhythm and blues drummer.

Cobb’s first gig in New York was with saxophonist Earl Bostic, a big name at the time known for his populist take on jazz virtuosity. By 1952, Cobb had left Bostic and was working with vocalist Dinah Washington, with whom he’d stay until 1955.

Earl Bostic: “Flamingo” (Grouya-Anderson), King, recorded 1951. This track was a number-one R&B hit; it’s exciting to realize that in 1951, the nation was dancing to Jimmy Cobb. Cobb is straight-ahead and confident, riding on an open hi hat and then on a cymbal.

Dinah Washington: “Trouble In Mind” (Richard M. Jones), Mercury, recorded 1952. Jimmy’s backbeat is high in the mix and grabs my ear, as emotional and communicative as Washington’s vocal. Cobb isn’t the only legendary jazz musician present on this cut: the brief tenor solo is by Ben Webster, and the blues piano tapestry is being woven by Wynton Kelly.

It’s amazing to think that behind “So What” and “Flamenco Sketches”, are George Russell, Debussy, and Ravel, but also, thanks to Jimmy Cobb, Earl Bostic, Dinah Washington, and a host of folks who loved this music.

But Cobb wasn’t the only Miles Davis drummer with a rhythm and blues background:

When I got to New York I joined a rhythm and blues band right away, with Joe Morris, Johnny Griffin, Elmo Hope,and Percy Heath. It was an 8-piece group. We barnstormed all over the country, from Key West, to Maine, to California. I stayed with them for 3 or 4 years, I guess.

Joe Morris had a lot of hits at that time. Today, you speak about a band having a number-one hit on the charts. In those days, Joe Morris had 3 or 4 hits going at once. He was making good money because he worked all the time.

—Philly Joe Jones to Rick Mattingly, Modern Drummer, Feb-March 1982

Philly Joe Jones, bebop titan and virtuoso soloist, began his career playing with two graduates of Lucky Millinder’s orchestra: trumpeter/vocalist Joe Morris and tenor saxophonist/vocalist Bull Moose Jackson.

Lucky Millinder was not an instrumentalist— he didn't play anything. Rather, he was a bandleader, MC, and presenter, based in NYC, who had some hit records in the Forties. One of these, “Who Threw The Whiskey In The Well?”, features loud handclaps on 2 and 4— imported from gospel music, this sound was a harbinger of things to come.

Here’s Philly Joe Jones playing some R&B:

Joe Morris: “Wow” (Matthew Gee), Atlantic, 1948. Written by the trombonist on the date, and featuring a hot solo from Johnny Griffin, plus support from Elmo Hope and Percy Heath, it’s fascinating to hear how bebop was packaged for the marketplace in 1948. Jones’ characteristic drive and presence are unmistakable.

Joe Morris: “Beans And Cornbread” (Morris), Atlantic, 1949. The gospel handclaps return here, Philly Joe is bashing 2 and 4, and Johnny Griffin is a convincing Illnois Jacquet rock and roller.

Bull Moose Jackson: “Bearcat Blues” (Jackson), King, 1952. The slow blues was a commercial concern at the time. Jones just keeps simple time on a snare drum with brushes, no major revelation but I value the track because it shows how revolutionary Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, and the rest of their cohort really were. As fun as these tracks and this sound are, the jazz masters had other goals.

Art Blakey had been working in this field before Philly Joe and Jimmy Cobb:

“One of the finest directors I played under was Lucky Millinder…the man was so fantastic, so talented! Ask anybody who worked with him. Ask Dizzy Gillespie; he’ll tell you…

And when he’d throw his hands down, you could bet your life that would be one! You didn’t have to count, all you had to do was watch him, and he wouldn’t make near a mistake at no time on any of the arrangements. This was a talented man.”

-Art Blakey to Arthur Taylor in 1971, published in Notes and Tones

Lucky Millinder, vocal by Annisteen Allen: “Moanin’ The Blues” (Lucky Millinder-Henry Glover), RCA-Victor, 1949. A decade before The Jazz Messengers recorded Bobby Timmons’ “Moanin”, Blakey was stomping out the time with a big band for a big hit.

Big John Greer: “Rockin’ With Big John” (Greer), RCA-Victor, 1949. Like Joe Morris’ “Wow”, Greer, another ex-Millinder soloist, and Blakey were bringing bebop to the masses. There are lots of good Blakey details on this track— Art’s cymbal beat, fills, and unmistakable passion make this cut a standout.

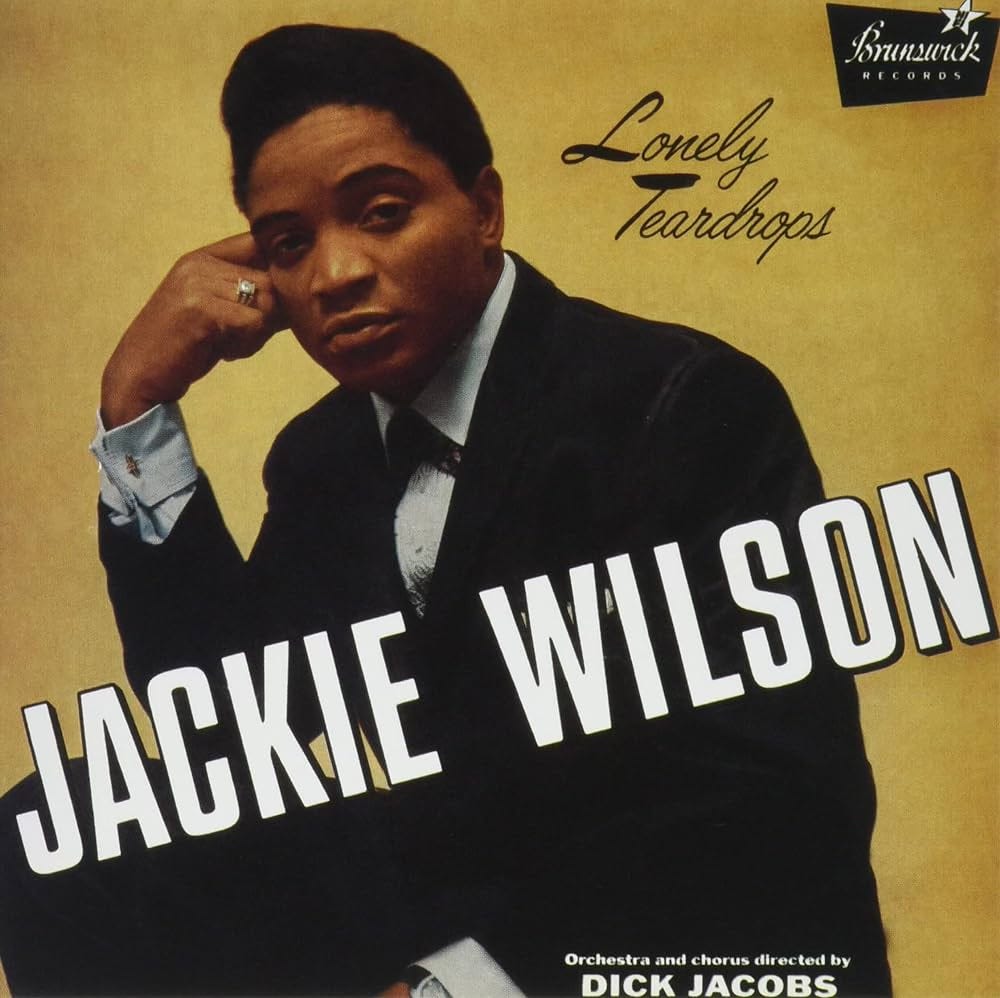

As a parting gift, the Lord Discography yields yet another treasure. Elvin Jones’ second recording session took place in Detroit, sometime in 1952. Led by saxophonist Billy Mitchell, the session featured Thad Jones, Elvin, and……Jackie Wilson, then known as Sonny Wilson, on vocals. Yes, THE Jackie Wilson, of “Lonely Teardrops”, with Elvin Jones.

Thankfully, YouTube has an upload of the song. The five-minute track I’ve linked below features both sides of the record: “Rainy Day Blues” is up first, followed by “Rockaway Rock”.

It’s startling and lovely to hear Elvin Jones, then 25 years old, doing a gig: backing up a singer, playing the backbeat, and swinging the band, with distinction and artistry. On “Rockaway Rock”, we even get a two-bar break from Jones:

I just love hearing these legendary jazz drummers play shuffles and beats, they sound so great.

There’s more to say and hear on this: Connie Kay, best known as a member of the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Panama Francis, who was Lucky Millinder’s main drummer, are on lots of R&B hits. I’d love to hear a thorough overview of their session work, so I shall work apace to bring this forth.

Part of what makes jazz so enchanting is that dual energy: the quietly innovative background musician. Standing just behind the classic recordings of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and Thelonious Monk are the shadows of dancers, comedians, theater shows, juke joints, and a huge audience. These few records are a sneak peak at those shadows.

Love those Jackie (Sonny) Wilson/ Billy Mitchell tracks!! Not surprised to read and hear that these great drummers "cut their teeth" in R'n'B bands as that music became the "lingua franca" of the Black working class during and after WWII. Great digging as always, Vinnie –– looking forward to the new Choir Invisible on Intakt!

Amazing post!