Adjust: Gerald Cleaver

The early years of one of our living masters.

I first heard drummer Gerald Cleaver playing with pianist Kris Davis at the Knitting Factory in 2002, and I was immediately intrigued.

His sound drew me in, made me feel right at home— controlled, focussed, and warm. But I was happily baffled by what he played. Where was he coming from, where did he learn to play like this? Nothing he did was typical, obvious, or a reference I could identify, yet everything fit together and made sense.

Soon after, I was able to meet and talk to Gerald. He couldn’t have been kinder or more generous— inviting me to his shows, giving me records to hear, telling me about drummers to study, dispensing advice and wisdom while we waited for the F train.

He’s been a presence in the music and in my mind for over twenty years: it’s time for a deep dive into his beginnings.

Like all jazz musicians, Gerald Cleaver’s music is rooted in his individual experience, his own life. But his music is just as1 deeply connected to his family, his mentors, and his community as it to his own singular life. Those three concepts— family, mentors, wider community— might be the pillars upon which Gerald’s made his mark. If I listen carefully, they’re present in every note.

Born May 4, 1963, Gerald Cleaver is a son of Detroit MI, and his his career embodies Detroit’s deep contribution to the music. His father, John Cleaver, was a noted jazz drummer who played with Joe Henderson, Tommy Flanagan, and others.2 Gerald grew up hearing jazz at home, and was playing drums as a child. In his teens, he branched out and got involved in Detroit’s music scene, forming tight connections with local masters including trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, saxophonist Donald Walden, and pianist Kenny Cox.

“Tony Williams, Jack DeJohnette, John Bonham, Elvin Jones, Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, Paul Motian, Roy Haynes and really, tens more. I have to mention the late great Roy Brooks3, Lawrence Williams4, George Goldsmith5 and Rich ‘Pistol’ Allen6 (of Motown fame) as four who I knew personally and were really encouraging to me, coming up.” — Gerald Cleaver to John Stevenson, arstash.com

In 1987, Cleaver enrolled at the University of Michigan as a music education major. By the early Nineties, Gerald was part of a diverse group of young players around Detroit including pianist Craig Taborn (a Minneapolis native) and saxophonist/composer Andrew Bishop, who became two of Gerald’s frequent collaborators. Other colleagues from this era were saxophonist J. D. Allen, bassists Tim Flood, Paul Keller, and Rodney Whitaker, and pianists Rick Roe and Jacob Sacks.

In 1993, Cleaver received a grant to study with master drummer Victor Lewis, first meeting him in NYC, later traveling with Lewis as he toured with saxophonist Bobby Watson’s group, Horizon. In an incident which he shared with me many times, it was on that trip that Victor told Gerald that he (Gerald) was a jazz musician, saying to him “you’re one of us”.

Four little words….“you’re one of us”….

With that tiny sentence, did Victor Lewis give something within Gerald permission to come forth? Did it unlock some inner voice or potential? Was Victor drawing out what was within Gerald, bringing forth what he knew was there?

“You’re one of us.” Those words have power. It’s almost like Victor Lewis cast a spell.

Cleaver made his first widely-available record on a date led by bassist and fellow Detroit native Rodney Whitaker. Whitaker’s Hidden Kingdom (DIW, recorded 1996) features Gerald on the Mingus-adjacent “Childhood”, and a few other tracks. It’s startling to hear Gerald’s confident, mature conception right out of the gate.

A real breakthrough was Roscoe Mitchell hiring me to be a part of the Note Factory in 1995. That singular event set me off on my career path. Looking back, Roscoe helped clarify my musical aesthetics which inform all of my playing, in both the so-called inside and outside. —Gerald Cleaver, 15questions.net

Perhaps best known as a founder of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, legendary multi-reedist and composer Roscoe Mitchell’s Note Factory7 was a nine-piece group which, at first, included two drummers (Gerald and Tani Tabbal), two pianists (Craig Taborn and Matthew Shipp), two bassists (William Parker and Detroit legend Jaribu Shahid) plus trumpeter Hugh Ragin and trombonist/composer George Lewis. In May 1997, this line-up recorded Nine To Get Ready for ECM.

Nine To Get Ready is excellent, focused squarely on Mitchell’s compositions and concepts. “Hop Hip Bip Bir Rip” starts in 3/4 but becomes a relentless surge, with Gerald (in the right channel) abandoning the meter and carving out his own space. On the swinging “Bessie Harris”, Cleaver is dense but transparent, going his own way while joining the fray, culminating in a duet with Tabbal (who’s playing djembe). “Big Red Peaches” is a brief, humorous rock tune, complete with distorted guitar, vocals and a heavy beat from Gerald.

By the late Nineties, Cleaver was busy. While living in Michigan, he recorded with legendary free improviser/saxophonist/pianist Charles Gayle (Precious Soul, FMP, 1997, available on Bandcamp)8, and visited NYC to gig and record with the new crop of up-and-coming players, including saxophonist Bill McHenry (Graphic, Fresh Sound, recorded 1998) bassist Chris Lightcap (Lay Up, Fresh Sound, recorded 1999), pianist Ben Waltzer (Metropolitan Motion, Fresh Sound, 1999), and guitarist Joe Morris with violist Mat Maneri (Live At The Old Office, Knitting Factory Records, 1999).

A whole host of brilliant drummers were coming to the forefront at the time— Jeff Ballard, Jim Black, Brian Blade, Adam Cruz, Rodney Green, Eric McPherson, Ben Perowsky, Jorge Rossy, Bill Stewart, Nasheet Waits, Kenny Wollesen, and others.

Individuals all, one quality they shared was an openness to every jazz practice, indeed, every musical tradition. It was all fair game— free improvisation, original tunes, swinging standards, global rhythms, chamber music textures, backbeats….. they could do all of it, on a high level, with style and individuality. With these drummers at work, NYC jazz was exploding with energy and possibility.

This is the environment in which I first heard Gerald Cleaver, and he seemed to epitomize the moment.

Five releases recorded in 2000 form a cross-section of Gerald’s music and provide some background depth to the music he’s making today9. Though there’s some shared personnel, no two records sound alike:

Craig Taborn: Light Made Lighter (Thirsty Ear, released 2001)

Matthew Shipp: Pastoral Composure (Thirsty Ear, released 2000)

Rene Marie: How Can I Keep From Singing? (MaxJazz, released 2000)

Gerald Cleaver: Adjust (Fresh Sound, released 2001)

Mark Helias: Roof Rights (Bandcamp, released 2020)

All of these records are streaming or available for download (go to Bandcamp for Mark Helias’ Roof Rights).

As always, the story of jazz is not the history of jazz on record. Records cannot tell the whole truth, but, heard in the proper context, neither can they lie.

Recorded in 200010 and produced by pianist Matthew Shipp, pianist Craig Taborn’s Light Made Lighter is a classic trio album, and one of the most important of the era. It spread like wildfire through my peer group and seemed like a new world. For those unfamiliar with Gerald Cleaver, start here.

Often, the compositions seem to consist of a bass line and little else. But what bass lines!— memorable, idiosyncratic, suggesting genres and traditions yet ultimately sounding like nothing but themselves.11 Taborn, bassist Chris Lightcap, and Gerald tease apart and expand upon the minimal written material, with much drama in the emergence of the theme from improvisation. Light Made Lighter is totally unique, very beautiful, quite mysterious, and a lot of fun.

The first track, “Bodies We Came Out Of pt. 1”, is an 8-bar bass line in a ponging 5/8. Gerald, holding a blastick and shaker in his right hand (with an empty left hand that eventually grabs a stick) weaves a detailed tapestry, on or just above the grid. unencumbered by the meter and form, yet still honoring both. Brilliant.

“Crocodile” begins in rubato, but Gerald subtly guides the trio to a straight-eighth 7/4 bass line, blending the two worlds— Cleaver is almost rubato over the 7/4 vamp and nearly in tempo during the rubato. At the top of “St. Ranglehold”, Gerald gently undoes a precise groove in 5/4 for a wild collective improvisation; when the melody enters, it feels inevitable.

The second version of “Bodies We Came Out Of”, as compelling as the first, concludes the album, slyly demonstrating the open-endedness of the music. That second take seems to say: this could go on forever.

No matter how many times I hear this album, I feel like I’m missing something, which is one of the great pleasures of recorded music. That feeling of missing something keeps us returning to our favorite records…..

Bravo Craig Taborn, Chris Lightcap, and Gerald Cleaver!

On pianist Matthew Shipp’s Pastoral Composure, Shipp and Cleaver are joined by bassist-composer-bandleader-impresario William Parker and the late, great trumpeter Roy Campbell Jr., huge personalities who define the sound of any group with their charisma and conception.

Cleaver, tellingly, is almost the straight man here. It’s a common jazz paradox, one heard all the time— Gerald is doing his own thing, seldom “interacting” with the soloists, which somehow makes the music more exciting, not less. Gerald’s relative reserve makes everything sound wilder and freer.

“Gesture” is a simple minor-key theme based on two chords over a pedal point, similar to a Mal Waldron or Keith Jarrett vamp. For the entire track, Gerald plays a subtly altering, flickering march on snare and bass— no cymbals, no toms, no fireworks. Killing.

“Visions” is a medium-swing D minor blues. While Shipp barks out an Ellington voicing and Parker walks, Gerald holds it down, playing the ride cymbal and some fancy bass/snare combinations.

“Frere Jacques” is special— I can’t imagine another group who could tackle a nursery rhyme so naturally and successfully. Gerald’s cool approach might be the crucial element, the necessary ingredient to make this work.

MaxJazz was an important label in the early 2000s12, with a special focus on vocalists. Singer Rene Marie was a late bloomer who launched her career in her mid-40s, and her success helped put MaxJazz on the map.

Recorded a mere seven days after Matthew Shipp’s Pastoral Composure, Rene Marie’s How Can I Keep From Singing? is a great album with a must-hear Gerald Cleaver performance. The rhythm section is truly all-star: Cleaver, bassist Ugonna Okegwo, and none other than Mulgrew Miller on piano.

For many musicians, going from Matthew Shipp to Rene Marie would be jarring, but Gerald shows the commonality. In fact, I heard the connection— the end of Pastoral Composure flows nicely into the beginning of How Can I Keep From Singing?, Matthew Shipp segueing smoothly to Mulgrew Miller, proof, if any was needed, that ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ are the same thing. Try it and hear for yourself.

Highlights are many: “Tennessee Waltz” is played in a nasty medium-slow 4/4 , with Cleaver’s strong, clear, supple beat in center frame: this is the truth. “Tennessee Waltz” in 4/4, that’s my kind of thing.

Elsewhere, we get a light, dancing backbeat from Gerald on Nina Simone’s “Four Women”, plus perfect ballad playing on “The Very Thought Of You”. I love the piano solo on “I Like You” (with great lyrics from Marie), a chance to hear Gerald and Mulgrew mix it up a little. Cleaver’s brushes on “A Sleepin’ Bee” are the law.

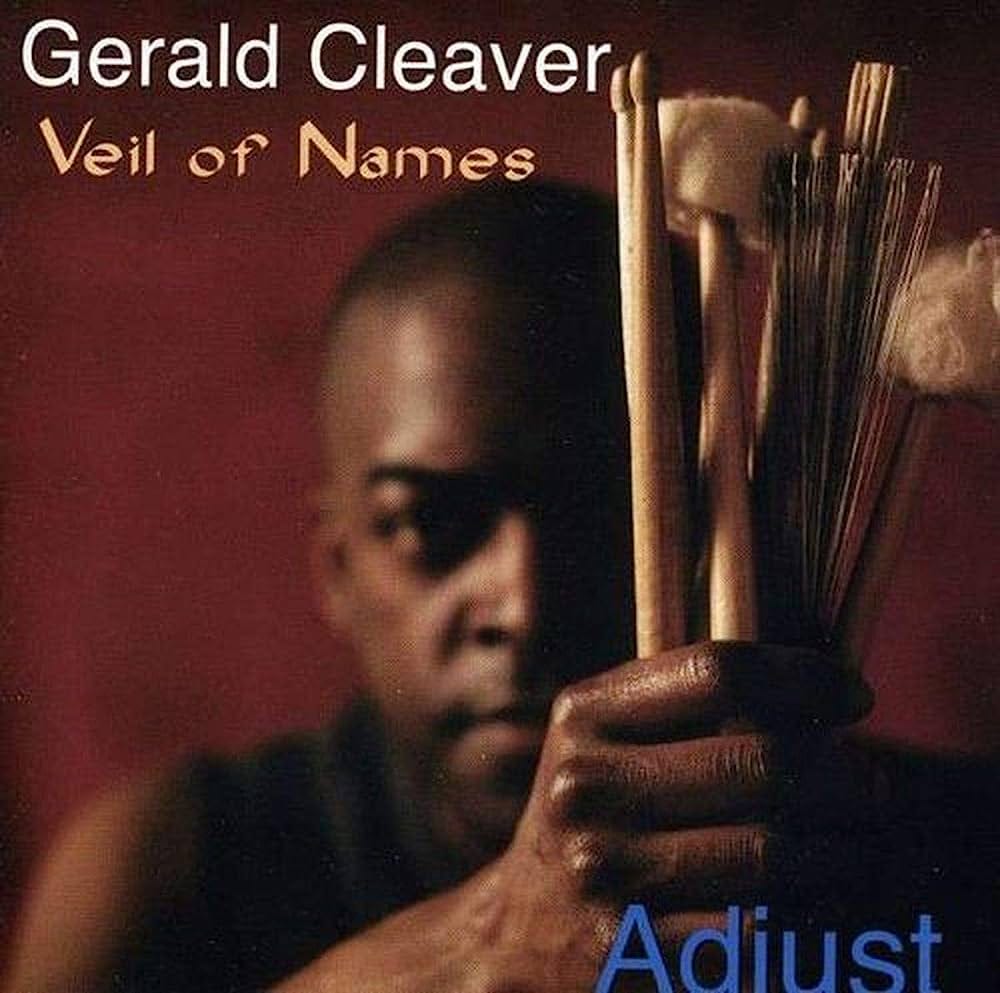

Adjust (credited to Gerald Cleaver Veil Of Names, a gorgeous band moniker), is Cleaver’s first leader date, rich with implications. Recorded in October 2000, and featuring a sextet of Cleaver, violist Mat Maneri, Andrew Bishop on woodwinds, guitarist Ben Monder, Craig Taborn on organ, Reid Anderson on electric bass13, Adjust pairs nicely with Jim Black’s first AlasNoAxis album: both are ‘electric’ albums with rock-like textures, both are drummer-led and drummer-composed, both recorded in 2000.

In New York, AlasNoAxis played at Tonic, and I bet Veil of Names did too. This was a scene, which helps explain why Adjust is so much fun to hear.

“Hover” is in rubato time, I suppose, but Cleaver generates such momentum and direction that ‘rubato’ doesn’t really cover it— just hear his multi-directional heat under Monder and Maneri’s co-solo. Cleaver and the band channel some CTI vibes on “Force Of Habit”, with Gerald’s huge slo-jam backbeat and Cobham-esque flourishes underpinning a great Taborn organ solo.

Of the longer suite-like pieces, “Way Truth Life” is the most wide-ranging. A gorgeous Monder intro gives way to a gently swinging melody and Reid Anderson solo, before morphing into a bass line that sounds like Light Made Lighter for a great Andrew Bishop clarinet solo.

Playing complex arrangements with a band of hot soloists, Gerald makes the transitions and contrasts feel natural and inevitable. He’s at home on some big drums with an electric sextet as he is with a kaliedoscopic piano trio. Adjust is a special record— it should be more widely heard.

Finally, in November 2000, bassist/composer Mark Helias’s Open Loose, a trio of himself, Gerald, and saxophonist Tony Malaby, traveled to Australia for the Wangaratta Jazz Festival. Helias arranged his music for sextet, augmenting the trio with trumpeter Scott Tinkler, David Ades on alto sax, and trombonist James Greening, three important Australian musicians. Recorded and released as Roof Rights, it’s a beautiful album of Helias’s expansive, genre-fluid compositions, and a fitting coda to our look at Gerald in 2000.

On Roof Rights, every facet of Gerald we’ve explored seems to come together— straight-ahead mastery (“Gentle Ben” is a slow, swinging 3/4, a personal favorite), avant-garde accelerant (“Pick and Roll”), selfless groover (“Handycam”), rock-jazz positivist (“Rocky Road”) and master ensemble player (“End Of Middle/Bing Bang”). Gerald lights up Helias’s brilliant music as naturally as his own.

Five records, each unlike the others, recorded over eleven months, nearly twenty-five years ago. Each sounds fresh and contemporary today; Gerald was making Future Music.

He’s doing it now too. Just check out his recent electronic albums Signs and Griots, both important, challenging, and a lot of fun, a new territory in his music14.

Music stitches people together in a profound way; Gerald Cleaver lives the experience of all music as one. But then, drummers have always disregarded boundaries between genres. Its drummers, I think, who most clearly show the human connections which undergird all the music we care about.

Happily, Gerald is alive and well. I can’t wait to hear what he’s up to next. I know I’ll hear his family, sense his mentors, and be a part of his community. Whatever he does is what we’ll all be doing, eventually.

Special thanks to Andrew Bishop, Tim Flood, and Jacob Sacks for their help with this essay.

Probably all jazz musicians, all artists, and really, all people make decisions based on family, mentors, and community, similar to Gerald. This must be one of the reasons his music speaks to so many.

Gerald once told me that when he (Gerald) played with Tommy Flanagan, they only way he could do it was by “looking like my father”. Not ‘playing’ like— looking like. That’s four years of jazz education in one sentence.

Brooks might be best known as a member of Horace Silver’s quintet in the Sixties. He was also a founding member of M’Boom, composer, bandleader, and force in Detroit.

Composer and drummer, an influence on Jeff Tain Watts, whose tunes were played by Kenny Garrett and Geri Allen.

Detroit drummer who can be heard on Horace Tapscott’s Lighthouse ‘79.

Best known for playing on major Motown hits (Martha and the Vandellas, “Heat Wave”, Junior Walker “What Does It Take?”, many many more), he can be heard on James Carter’s Live At Baker’s Keyboard Lounge (Atlantic, 2001) playing a beautiful shuffle on “Foot Pattin”.

There are at least four Roscoe Mitchell releases featuring Gerald:

The Day And The Night (Dizim, recorded 1996)

Nine To Get Ready (ECM, recorded 1997)

The Bad Guys (Il Manifesto, recorded 2000)

Song For My Sister (Pi Recordings, 2002)

In addition to Precious Soul, Gerald is also on Charles Gayle Shout! (Clean Feed, 2003).

Gerald Cleaver participated in at least 11 recording sessions in 2000; other important releases from that year include Mat Maneri Blue Decco, Roscoe Mitchell The Bad Guys, and Matthew Shipp New Orbit.

No recording date is given in the liner notes to Light Made Lighter; the Lord Discography lists “ca. Jan 2000”. Anyone with other info, please inform me!

Craig Taborn Chants (ECM, 2013) with bassist Thomas Morgan, is very much a development and deepening of the sound and concept of Light Made Lighter.

MaxJazz released great records by Bruce Barth, Mulgrew Miller, Jeremy Pelt, and Frank LoCrasto, and many more. According to Wikipedia, they were bought by Mack Avenue in 2016; as far as I know, their whole catalogue is streaming.

Reid Anderson plays acoustic on “Hover” and “Way Truth Life”, only two tunes out of seven.

Four Gerald Cleaver-led records I listened to for this article, all are great, all should be heard:

Detroit (Fresh Sound, 2007)

Be It As I See It (Fresh Sound, 2010)

Life In The Sugar Candle Mines (Northern Spy, 2013)

Live At Firehouse 12 (Sunnyside, released 2021)

I'm so glad to see you paying tribute to one of the greatest musicians of my lifetime.

I've heard almost every recording you talked about, and it is amazing how different all of them are, yet Gerald sounds like himself on every one.

The recordings he did with Chris Lightcap's groups Bigmouth and SuperBigmouth stand out to me as some of the best representations of the cutting edge of composition and improvisation in the first 2 decades of the 21st century, and I couldn't imagine them be as amazing as they are without Gerald Cleaver's musicianship and framing at the drums.

Thank you Vinnie!

Invaluable. Thank you for doing this. Conveniently, I am chasing Gerald for a conversation about his newer "techno" work