For Al Foster:

Hank Shteamer’s beautiful and informative NY Times obituary;

Ethan Iverson considers and celebrates Foster with Joe Henderson; with Tommy Flanagan and Steve Kuhn; with the Milestone Jazzstars;

Bassist Doug Weiss’s heartfelt, poetic essay captures Foster’s indomitable spirit.

I’ve been working on an overview of Al Foster’s extensive discography— so much great music, so many human stories. This first part covers his recordings with Blue Mitchell, dates with Monty Alexander, Illinois Jacquet, and Larry Willis, and then three selections that summarize Foster’s work with Miles Davis, music that avoids a critical consensus over a half-century later.

The story of music is the story of human connections, of ideas that bind us. This is a tiny slice of that story.

YouTube playlist is here, or you can click on individual selections.

Aloysius Foster, born January 18, 1943, was living with his family in Harlem when, at age 13, he became taken with the drums:

“The very first thing that really made me want to play drums was Max Roach and Clifford Brown's "Cherokee." That was when I got serious…After I heard Max, I really started checking modern jazz, bebop, and hard bop.” 1

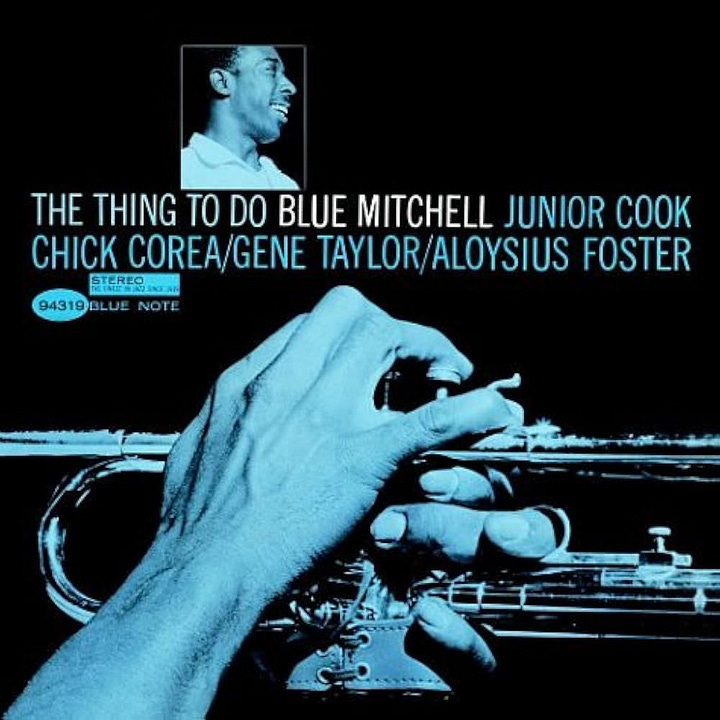

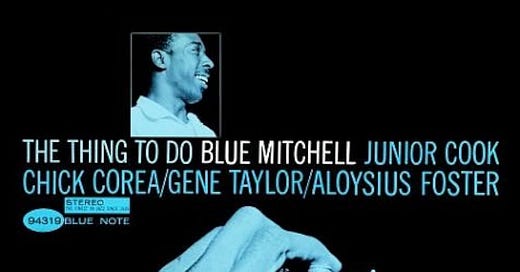

Ira Gitler mentions Foster playing with trumpeter Ted Curson2 prior to subbing for Roy Brooks with Horace Silver at Birdland in 1963. When trumpeter Blue Mitchell, who with tenor saxophonist Junior Cook and bassist Gene Taylor had been with Horace Silver since 1959, organized his own group, he asked Foster and a then-unknown Chick Corea to join. Two Blue Note releases under Blue Mitchell’s name— The Thing To Do (1964) and Down With It (1965)— are classic records with standout Foster performances.

Blue Mitchell: “Fungii Mama” (Mitchell), from The Thing To Do! (Blue Note, 1964). Blue’s calypso was the hit from Foster’s first record date and the most well-known tune from Al’s tenure with Mitchell. It’s telling that at the outset, Foster is playing a dance rhythm—almost a backbeat— for his life at the drums was spent, in part, connecting all the dance rhythms to the 4/4 swing he loved and mastered.

Blue Mitchell: “Chick’s Tune” (Corea), from The Thing To Do! Here’s s the young virtuoso doing what he was born to do— Foster’s swinging ride cymbal (with strong hi-hat handclap), plus improvisation on the snare and bass in tandem with the soloist, is a conceptual and technical feat. “Chick’s Tune” shows that in 1964, Al Foster was a young hard-bop master in a class of his own. Though they knew the language, none of Foster’s peers, including Al’s favorites Tony Williams (born 1945) and Joe Chambers (born 1942) were playing it with such discipline and vitality at the time.

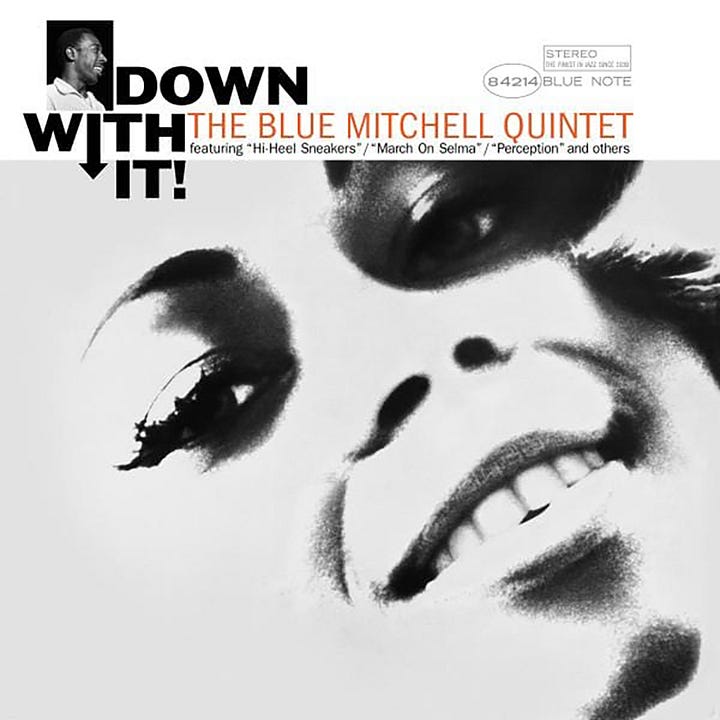

Blue Mitchell: “Hi-Heel Sneakers” (Robert Higginbotham), from Down With It (Blue Note, 1965). Mitchell’s quintet embraces and celebrates the ubiquitous Blue Note boogaloo, which Foster plays unaffected, occasionally hitting hard and playin loud. Al later deployed a version of this beat for hours of Miles Davis’s most controversial music.

Blue Mitchell: “One Shirt” (William Boone3), from Down With It. Here, the Al Foster we know and love is present, hard bop mastery that’s a little more opened up than on “Chick’s Tune”. His singable tom-tom melodies— Max Roach distilled to a melodic essence— are played with the detail and nuance of a classical percussionist; the clarity, originality, and correctness of both Foster’s ideas and execution set him apart early on.

The Blue Mitchell gig put Al Foster on the map. But as a single father in NYC (“At the time I started raising them, my oldest girl was seven, and my youngest was 14 months old. So I couldn't work with anybody, as far as going on the road.”4), Al declined offers to join Horace Silver, Cannonball Adderley, and Wes Montgomery. Instead, he remained at home, playing local gigs and making the occasional record date, devoted to raising his four daughters.

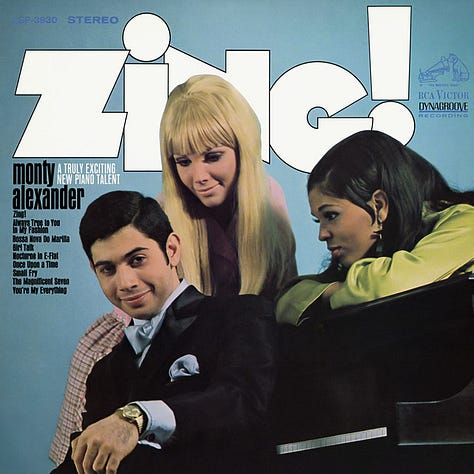

Monty Alexander: “Small Fry” (Hoagy Carmichael-Frank Loesser) from Zing! (RCA Victor, 1967). Though Foster’s not yet using his signature vocabulary, the clarity of the cymbal beat and nuanced tones on the snare and bass announce the presence of a master. Foster’s the perfect choice for this session, thriving, at ease, and happy to be swinging with Bob Cranshaw and Monty Alexander in a way that his peers (Tony, Joe Chambers, Jack DeJohnette) probably would not.

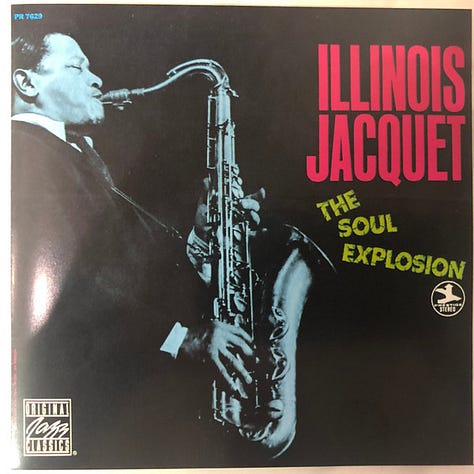

Illinois Jacquet: “The Eighteenth Hole” (Gladys Bruce, arranged by Jimmy Mundy) from The Soul Explosion (Prestige, 1969). Al Foster with an 11-piece band, setting up the brass, playing the arrangement! Incredible. This is Foster in 1969, bringing musicianship and a fresh, youthful creativity to a record date of Swing Era masters. If I heard “The Eighteenth Hole” in a blindfold test, I would never guess it was Al Foster, but when I was told it was him, it would seem obvious.

Larry Willis: “The Funky Judge” (A. Williams-L. Hutton) from A New Kind Of Soul (LLP Records, 1970). Pianist Larry Willis was a native New Yorker, born just a few weeks before Foster, who had a unique affinity to Al. Foster’s really opening up on Willis’s great version of Bull and The Matador’s Top 40 hit, hitting a little harder, inching close to a sound that the world would soon know, courtesy Miles Davis5.

Though he wasn’t touring, Foster was staying busy with steady gigs, first playing nightly at the Playboy Club in midtown Manhattan from roughly 1965 to 1970, and then at a restaurant called the Cellar. It was at the Cellar that Foster and Miles first connected:

Miles started coming in there [The Cellar] twice a week. Miles dug my cymbal beat. That's what he told me. He thought it had a real hip jazz feel.

My ride cymbal playing reminds me of Arthur Taylor. That's what I hear. At that time, Miles said he heard some Art Blakey and Philly. But when I was coming up I was really influenced by Arthur Taylor's swing. Not his solos so much, but his right hand—the feel of it. At one time during the '50s and early '60s, Arthur Taylor recorded more than anybody. He's on most of the Prestige records, with everybody. He did stuff with Miles, and quite a bit of stuff with Coltrane. He's on Giant Steps. Check that record out; check out the cymbal beats he was playing. I'm really influenced by him a lot. I mean, this guy swung.6

Though it was Al’s cymbal beat and bebop knowledge that enchanted Miles, it was Foster’s backbeat and openness that Davis used extensively. For three years, Al Foster was the drummer most often heard with Miles Davis, from the release of On The Corner in 1972 until Miles’s hiatus in 1975. This is Davis’s most controversial era, music that refuses reductive understanding.

Miles Davis: “Rated X” from Get Up With It (Columbia, recorded 1972). Foster’s beat, a two-bar pattern on hi-hat, bass, and snare strongly connected to James Brown (especially “Cold Sweat”, with Clyde Stubblefield on drums), is the glue holding together this famously extreme Davis track. The frenetic energy of Foster’s beat, which Foster hardly varies, is the emotional underpinning for Davis’s haunted, maddening organ solo. Aggressive and despairing, “Rated X” continues to affront7. Al sounds great.

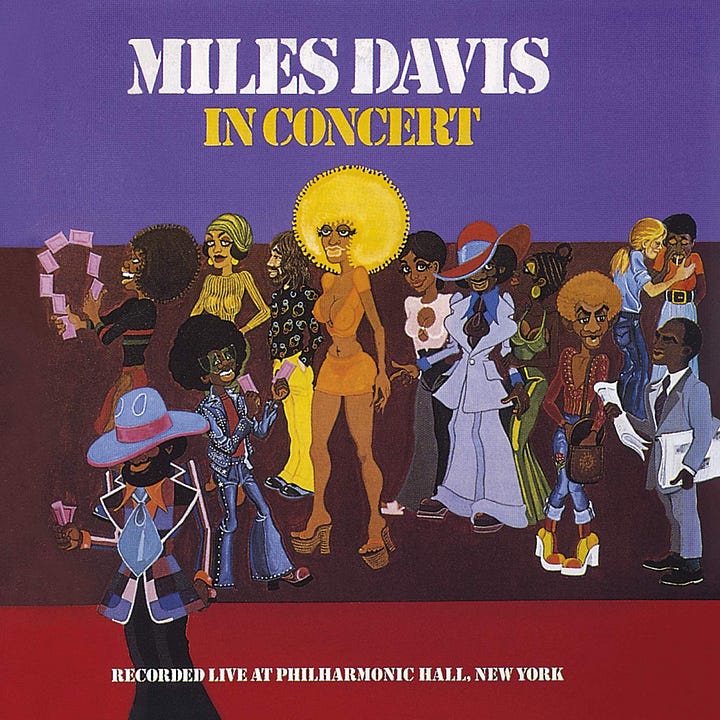

Miles Davis: “Right Off” from Miles Davis In Concert (Columbia, recorded 1972). A powerful example of Foster’s musicianship and technical accomplishment— it’s really hard to play a deeply swinging, dynamically varied, medium-up, two-handed shuffle with the strength and clarity needed to cut through two percussionists, electric guitar and sitar, electric bass, keyboard, wah-wah trumpet, and soprano sax. This isn’t the most coherent Davis track, but Foster keeps it admirably grounded with his marvelous shuffle.

Miles Davis: “Maiysha” from Get Up With It (Columbia, recorded 1974). 37 seconds into “Maiysha”, Foster plays his signature Davis-era beat: 16th notes on an open hi-hat, backbeat on the snare, syncopated bass drum (both subtly varied), at about 60 beats per minute. A hypnotic beat, with droning overtones from the open hi-hat, it’s the base upon which Miles built his minimal, process-oriented pieces of the era. At 15 minutes, “Maiysha” is succinct by Davis’s standards of the time, and summarizes Foster’s contribution to Miles’s music— as Davis directs the ensemble from the organ, or with his trumpet (sometimes cycling through an 8-bar form, sometimes discarding the form and dwelling on a chord; cueing melodies, solos, and a final two-chord vamp), it’s Foster’s musicianship, taste, and bebop-honed sensitivity that keep it all together. Al Foster is playing his heart out, and Al and Miles shared a deep understanding, easy to hear on “Maiysha”. In a sense, it’s Al’s humanity and musicianship keeps Davis’s 1972-75 music from veering into chaos. He’s the last man standing.

When Miles Davis, beset by physical illness and spiritual malaise, went on hiatus in late 1975, Al Foster was at liberty, a premier NYC jazz freelancer. The next piece will track his work with both Davis’s bebop-era peers and the thought leaders of Foster’s own generation, culminating in Al’s long collaboration with Joe Henderson, one of the great partnerships in the music.

Respect and gratitude— for your time, and for Al Foster.

“Al Foster” by Robin Tolleson, Modern Drummer, January 1989.

And a vibraphonist named Vera Auer, of whom I’ve never heard.

According to the liner notes to Down With It, Boone was a pianist friend of Mitchell’s in Miami, FL.

“Al Foster” by Robin Tolleson, Modern Drummer, January 1989.

In Miles: The Autobiography, Davis recalls Larry Willis playing piano with Al Foster at the Cellar in 1972, and says that, on his recommendation, Columbia Records taped the group in performance at the Cellar. No album was ever released. I assume that Zev Feldman and company are on the case.

“Al Foster” by Robin Tolleson, Modern Drummer, January 1989.

I listened to a lot of Davis’s 1972-75 era music preparing this post. Some of the records I checked in on— On The Corner, Get Up With It, and Agharta especially— are widely praised now. I collected and listened to them all in my teens and twenties. I thought they were great, if a little baffling. But I’m starting to wonder if Stanley Crouch, who famously attacked this music, understands it far better than I and the many critics who celebrate it.

Re: footnote 7, no, Stanley Crouch does not understand that music.

Very interesting piece again. Thanks. (Was just about to mention that footnote 7 will not pass unnoticed!)