Archie Shepp and Philly Joe Jones

Three Archie Shepp albums shed new light on Philly Joe in the Sixties.

Hank Shteamer is one of my favorite writers. He’s passionate, informed, and scrupulously honest. I learned a lot from his great Substack piece about saxophonist Noah Howard’s recordings with drummer Art Taylor, which inspired me to investigate the records Philly Joe Jones made with Archie Shepp.

Thanks to Dan Weiss, I’d known for years that Philly Joe Jones and Art Taylor, both living in Europe during the tumultuous late Sixties and early Seventies, had recorded with some free musicians, but I’d never investigated. Hank’s article pushed me to go a little deeper— thank you Hank, thank you Dan.

In 1958, drummer Philly Joe Jones had reached a peak. Having set a new standard as a member of the Miles Davis Sextet, showing the world the brilliance of Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderly, Red Garland, and Paul Chambers, Jones left Davis’s group to freelance and lead bands in NYC.

He worked steadily and with distinction in New York, but in late 1963, Philly Joe relocated to Los Angeles. Though Jones found work easily enough, the move was, ultimately, short-lived.

In late 1966 and the first half of 1967, Jones appears on several record dates in New York; I wrote about one such date here, a Bill Evans session recorded live at the Village Vanguard in the summer of 1967. Had Philly Joe moved back to town?

If he had, it was temporary. Jones was soon on the move again, arriving in London with the intention of staying. Philly Joe Jones applied for membership in the English musician’s union sometime in 1968, ten years after leaving Miles Davis.

1968 was a year of political violence and widespread social unrest across the USA and Europe. For jazz aficionados, 1968 was, among other things, the time of the ‘ex-pats’, ex-patriate Black masters who had moved from the States to Europe.

A partial list of ex-pats includes Don Byas, Don Cherry, Kenny Clarke, Dexter Gordon, Johnny Griffin, Albert Tootie Heath, Art Taylor, and Mal Waldron. Some, like Byas and Clarke, had long made a home in Europe, while others like Griffin and Philly Joe, were more recent arrivals.

Clearly, the ex-pats were reacting, in part, to the unending ugliness of racism in the USA and the growing impossibility of making a living in the music. Obviously and sadly, these two phenomenon are related.

But, as they soon discovered, with a little luck, in Paris, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and other cities, great Black musicians could create a life geographically and spiritually removed from the harshness and limits of America.

As society was changing, so was the music. In the Sixties, jazz had opened itself up to new ideas from countless sources, from folk traditions across the world to contemporary classical practice, renewing itself as it always has. But despite the music’s undiminished vitality, the Sixties witnessed a steep decline in jazz’s commercial viability.

To a veteran grand master like Jones, born in 1923, the situation might have seemed serious, perhaps even dire. Maybe a splintering society, departing compatriots, and rapidly evolving music scene called for a complete change of scenery.

Musically, Paris was a good place to be in the summer of ‘69.

An influx of young and fearless American jazz musicians, including a cohort of Chicagoans from the AACM, including the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Anthony Braxton, Leroy Jenkins, and many others, were new in town and making waves, as was tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp.

Shepp was coming off a triumphant and deeply influential July performance at the 1969 Pan-African Festival in Algiers, a high point of the Pan-African arts movement, where Archie played a concert with his own group plus an ensemble of African musicians. This must be one of the first times a Black American jazz musician had publicly collaborated with an African ensemble. New ways of living were being imagined daily.

So, that August, on what must have been a creative high, Shepp spent eight days (the 11th to the 18th) in a Paris recording studio, recording three full-length LPs of his own, and playing on records by Grachan Moncur, Dave Burrell, Sunny Murray, and others. On drums for all three Shepp-led albums was Philly Joe Jones.

BYG, a French record company caught up in the spirit of the era, released it all, giving us a glimpse of that fiery, intense, all-or-nothing moment, an inflection point in the music when the spirit of rebellion, protest, and Black power infused every note played.

But before we get into the records, we need to think about Archie Shepp.

Archie Shepp understands theater and music. I’d loved a few Archie records for years, but didn’t really get him until seeing him at the Vision Festival in 2018.

On stage at Roulette, in a hat and suit, before he’d played one note, Shepp was rock-star charismatic. His physical presence was electric— he seemed 10 feet tall, and commanded everyone’s attention with minimal effort. Everything he did was an artistic act: every word out of his mouth was a speech, every move a dance. His stage announcements had a dramatic effect: when he said “William Parker on bass”, I found myself silently pondering the deeper meaning of his words.

When he finally played, after making us wait, letting the anticipation build so as to have maximum impact, it was seismic, the air in Roulette was vibrating, and I almost jumped out of my seat.

I finally got it. Archie Shepp is a giant.

This awareness of drama, of heightened reality, hums through Shepp’s three BYG albums with Philly Joe, who himself was no stranger to the dramatic arts. Let’s hear from Art Blakey:

[Philly Joe Jones] is a great artist, and I admire his talent. Philly is much more than a drummer; he’s a natural actor. It’s such a shame that this country, this society, lets a talent like his go to waste. It just kills me inside. This man has so much more to offer than just playing the drums; he can do anything.

-Art Blakey to Art Taylor in 1971, from Notes And Tones, page 247.

A natural actor?? Clearly, I know nothing about Philly Joe Jones!

But we all know what Blakey means— we can hear it on the records, loud and clear. It’s one thing to play the drums like Philly Joe— it’s quite another to generate that charged, anything-can-happen atmosphere.

This is the highest level of mastery.

All of these elements— Jones’s travels in response to a changing society, jazz’s evolving social meaning, ex-pat Americans putting together a life in Europe, and Pan Africanism— came together for a week in August 1969 in a Paris recording studio.

The three records of Shepp’s featuring Philly Joe are great— strong, uncompromising, challenging, and rewarding. With cameos from Lester Bowie, Malachi Favors, and Roscoe Mitchell, plus memorable turns from Jeanne Lee, Dave Burrell, Grachan Moncur, and Hank Mobley, the Shepp BYG trilogy is a great cross-section of the music in 1969.

They allow us to hear, in the person of Philly Joe Jones, how the new thinking in jazz was assimilated by the older generation.

Here’s a whole side of Philly Joe that I sort of knew existed, but had never checked out. Hearing Jones with Archie rounds out and deepens his stunning achievement. As I listen over and over, I keep thinking “This is the cat from “Billy Boy” with Red Garland”. There’s no “Billy Boy” anywhere in sight, and yet, it’s folded into the sound. Philly Joe Jones is as ready for the future as anyone.

The three albums are:

Yasmina, A Black Woman (BYG, 1969), recorded August 12, 1969.

Poem For Malcolm (BYG, 1969), recorded August 14, 1969.

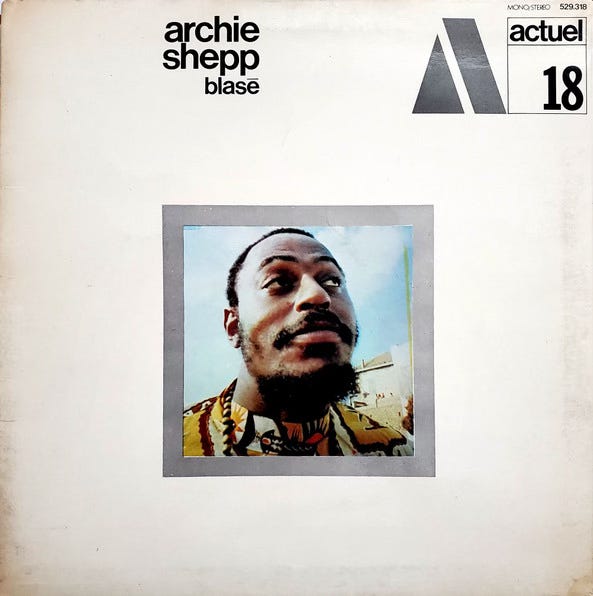

Blasè (BYG, 1969), recorded August 16, 1969.

“Yasmina, A Black Woman”, Shepp’s title track, begins with a great free Philly Joe solo— gestures and energy, plus some flash and wisdom, even the fanned hi-hat. Welcome to the new world.

Eventually, Shepp begins singing and chanting, calling the spirits down, and the band enters, vamping on two chords. Jones leads the percussion section (Sunny Murray on high jangling sounds, and Art Taylor on logs!) through a series of solos and backgrounds featuring Shepp, pianist Dave Burrell, and altoist Arthur Jones, a new name to me, sounding great.

On Side 2, Hank Mobley joins the young firebrands for a blues in F. Shepp plays trombonist Grachan Moncur’s “Sonny’s Back”, and then hands it off to Mobley. The first time I heard this, I didn’t realize that Hank soloed first— I thought it was Shepp in a more straight-ahead mode. I am learning, I am learning.

Mobley solos until about 3:20, and then Jones and Malachi pick up the tempo, which, the more I listen, the more I think has to be on purpose, at least on some level. After all, the unsettled, slightly out-of-focus 4/4 swing works perfectly for Shepp. I can’t imagine a Shepp solo with a nicely swinging Philly Joe a la Kelly At Midnite. That would not work.

This track neatly summarizes how much the music had changed— what might have been an easy walk down the street in 1964 is now a forum for passionate, almost ungovernable feelings.

Fittingly, we wrap up with a straight, almost conciliatory (but poorly recorded) reading of “Body and Soul” with Shepp and the rhythm section.

Yasmina, A Black Woman is almost like a set at a jazz festival— a new piece for large ensemble, a blues with a special guest, and a ballad to say goodnight. Poem For Malcolm, recorded two days later, is more experimental, deeply connected to theatrical presentation and drama— heightened reality, high stakes, total commitment. Incredible.

On Shepp’s “Mama Rose”, two drum sets played by Claude Delcloo and, according to Discogs, Micheline Pelzer, create a noisy, dizzying swirl that offsets Shepp and pianist Burton Greene effectively, while unfortunately burying Philly Joe’s tympani bombs.

“Mama Rose” eventually becomes “Poem For Malcolm”, beautifully and intensely recited by Shepp. Whatever flaws in execution, we can’t doubt the sincerity and seriousness of Shepp and his cohort.

A long, unaccompanied Shepp solo opens “Rainforest”, where he returns to a few motifs without much fuss. With his voice in our ears from “Poem For Malcolm”, we can hear that Shepp’s speaking voice and tenor sound are one and the same. Eventually, the atmosphere heats up; Philly Joe enters, exits, gingerly and then forcefully re-enters, playing loud, proud, and virtuosic, foreshadowing the sparks he and Shepp will generate on Blasè.

At the last minute of the track, Shepp plays, of all things, Sonny Rollins’ “Oleo”, with Mobley and Moncur joining in and Jones taking the bridge. Jazz is full of mysteries. What does “Oleo” mean, played by these musicians in this context?

Frankly, I’m sort of shocked that this was recorded: it feels like an event, a once-in-a-lifetime gathering. We are so lucky to hear to the explosive, barely-contained energy of these musicians, at this time.

Blasè is the most balanced of the trilogy, and stands out for the presence of Jeanne Lee, a thespian and musician on a par with Shepp and Abbey Lincoln who steals the show. The album presents a dizzying array of styles— a one-chord blues, something from theater, spirituals, Ellington’s world, and improvisation.

On Shepp’s “My Angel”, two harmonicas suggest a street corner, and our hero Archie Shepp comes on stage, dusty from the road. Jeanne Lee is unfazed by some intonation questions, and simply tells her story. Eventually a sort of fast quasi-backbeat develops, with Philly Joe on brushes and Dave Burrell admirably committing to his simple part.

Only Jeanne Lee could handle Shepp’s “Blasè”, bringing Archie’s provocative text perfectly to life. Joe is totally in the piece, tinkling glasses and knocking on doors and in counterpoint.

The traditional hymn “There Is A Balm In Gilead” is simply and beautifully arranged; Lee’s brief, unaccompanied solo is a high point in all three albums. If “Blasè” was a Saturday night lover’s spat, then this is Sunday morning.

Burrell’s intro to “Sophisticated Lady” brings Cecil Taylor to mind, but he magically and seamlessly transitions to Jeanne Lee and the song. Minus the intro, the focus is strictly on inhabiting the tune, and the moment of Shepp soloing with rhythm section is a cool drink of water after the heat and intensity of Yasmina and Poem For Malcolm.

That heat returns on “Touareg”, recorded by a trio of Shepp, Philly Joe, and Favors. This is the one I’ve been waiting for, this is the track Dan Weiss showed me years ago that alerted me to the Philly Joe/Archie Shepp connection.

The title refers to the Turaeg people of Northern Africa, a group of whom played with Shepp at the Pan-African Festival. With this title, Shepp is explicitly connecting the group’s sound to evolving ideas of Black identity and possibility in 1969, ideas he was embodying and embracing.

At the outset, Joe displays his version of the Sunny Murray/Rashied Ali multi-directional concept, knitting a thick tapestry of sound and color which allows the soloist to play fast, slow, or anything in between. Philly embraces this sound so whole-heartedly that I start to wonder if he and his crew had been occasionally playing like this for years, maybe only in private.

Happily, there’s a dash of razzle-dazzle and pizzaz to Jones’s free playing; he simply cannot help but entertain and wow us while forging his new path. Even when he’s opening up with Archie Shepp, Jones, who always named Buddy Rich as an influence, sounds like a man in the spotlight. “Touareg” is a lot of fun.

Favors jumps in, a little under-recorded, but filling out the space nicely; later in the piece we can hear him better. The energy is relentless, and Joe sounds right at home. Eventually, the whirlwind gives way, and Shepp, Favors, and Philly Joe find an ending, bringing the BYG trilogy over the finish line.

I’ll be listening to these records a lot more, I’ve just scratched the surface of what they contain.

The wave of changes come, the tide of understanding and acceptance goes in and out. One thing is for sure: Philly Joe Jones always knew what to do.

POSTSCRIPT: There is an LP entitled Archie Shepp and Philly Joe Jones on a label called America from 1969. It is not streaming anywhere, but I ordered it on Discogs.com this morning. I’ll be making my report as soon as I can.

Thanks again to Dan Weiss and Hank Shteamer….

In the very late 70's (early 80's?), there was a club on one of those streets between Washington Sq. and Broadway that only lasted a short while. Rumor had it that it was owned by Bill Cosby but Philly Joe was running it. A friend and I were passing by during daytime hours, noticed it was open and went in for a drink. Joe was socializing with a small group around a table and warmly welcomed us into the bar as we were the only other customers. As we were sipping, one of the guests with Joe got up and walked to the stage. It was Art Taylor who went on to give us all a brush solo at the kit! I'll never forget that surprise treat but have never been able to remember what this short-lived club was called. I always meant to email Phil Shaap, sure that he would have the answer, but alas! Does anyone know the name of that joint or did I invent it in a dream?

Thanks for the tip on this one https://youtu.be/FtIRMOYb6bU?si=5emRKnfQnc-29TpB just listened for the first time. A demonstration of one the trends from this period where the bass and drums weren’t necessarily going to focus on hooking up on the quarter note. Even when the music is in time, there’s a sense of simultaneous tempos, rather than hooking up on one tempo. Creates an interesting texture.