Joseph Rudolph “Philly Joe” Jones was born July 15, 1923, 100 years ago last Saturday. Since his death in 1985, musicians and listeners have kept his name alive, his music in our ears. His brilliant playing on the recordings that define jazz ensures that his name will be known long past the foreseeable future.

Jones’ vocabulary was completely his own— what he borrowed from Sid Catlett, Buddy Rich, and players unknown to me was always recast in Jones’ idiom. For drummers, learning a Philly Joe Jones solo is a rite of passage, a gateway to a bigger world.

One of the most trained, hugely accomplished musicians of his era, Jones was fluent on piano, bass, saxophone, and voice. He was an arranger, occasional composer, as well as a tap dancer, comedian, and natural actor1.

Jones was a singular force in the music. Grappling with Philly Joe is a must for for all musicians and listeners, essential if one wants to learn. He is foundational.

One strand of Jones’s excellence was his way with the rudiments. When Jones was a teenager, studying drums meant reading music and playing dozens of rudimental solos. Among drummers, it’s common knowledge that Philly Joe’s solo vocabulary was heavily influenced by Charles Wilcoxon, a Cleveland-based drummer and educator2.

As I think about it, however, this fact becomes strange. It shines a light on Jones’ specialness and the breadth of his intelligence. Hundreds of drummers in the Forties and Fifties must have played Wilcoxon’s snare drum pieces, collected in books like Modern Rudimental Swing Solos For The Advanced Drummer and others. But only one person took Wilcoxon’s ideas and translated them into an emerging modern jazz idiom.

To take a book of rudimental snare drum etudes, one which makes no reference to Duke Ellington or Count Basie, much less Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk, and find within it a key to advancing jazz is supreme genius, like a poet finding new textual possibilities in a book on penmanship. But then, repurposing the flotsam of American culture has always been the purview of the jazz musician. This curiosity— Jones’s transmogrifying Wilcoxon— when considered, underlines Philly Joe Jones accomplishment, creativity, and contribution. Only Philly Joe could do what he did with Wilcoxon.

Like most of us, I can’t get enough of Philly Joe Jones. The humor, the wit, the flash, the excellence, the excitement, the drama….Philly Joe Jones is so great as to be almost a jazz sub-genre. A big thank you to all my teachers and peers for showing me how much music Jones made while accompanying the giants: Clifford Brown, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Red Garland, Sonny Clark, Dexter Gordon, Elmo Hope, Hank Mobley, Freddie Hubbard….

On Saturday, I turned on the 24-hour Philly Joe birthday broadcast on WKCR, and heard some cuts from dates he led for Riverside— Blues For Dracula3, Drums Around The World, Showcase. Great stuff of course, with lots of incredible drum solos. But in addition to being a virtuoso soloist, Philly Joe Jones was a master interpreter and selfless collaborator. I sometimes lose sight of this, so enchanting and jaw-dropping is he when he solos.

There’s a lot wrong in the world, but it’s summertime and life is beautiful. So I’m going to put on one of my favorite Philly Joe albums, enjoy some coffee, and celebrate Jones’s 100th birthday anniversary.

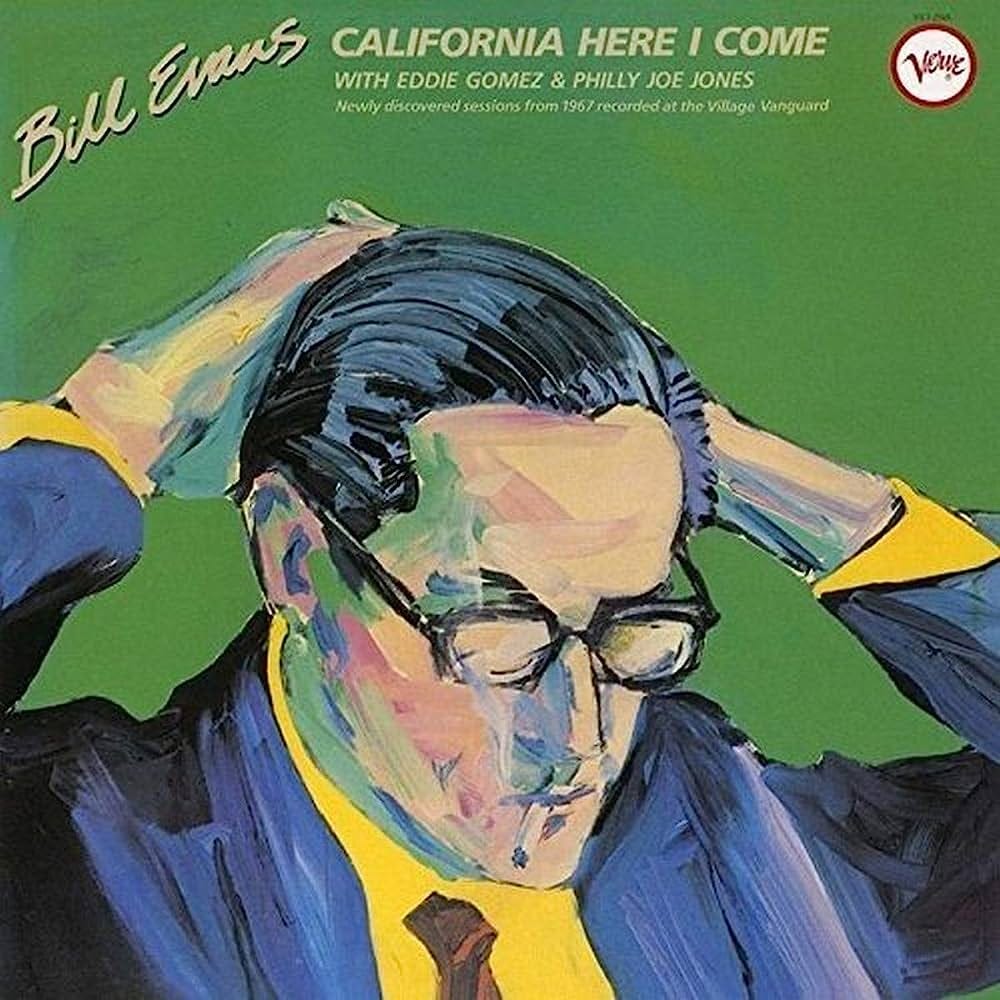

I’ll honor Philly Joe Jones’ birthday by listening to a posthumously released, gorgeously recorded Bill Evans set on Verve called California Here I Come. Taped in August 1967 at the Village Vanguard, the trio is Bill Evans, Eddie Gomez on bass, and Philly Joe Jones.

In 1967, Jones was only recently back in NYC, after living on the West Coast since 1964. Soon, he would make his way to Europe, where he would be based until the mid-Seventies. This album is a sort of parting gift from Jones, on his way to new horizons.

Down the stairs of the Vanguard I go, take my seat near the drums, and settle in…..

“California Here I Come”. Only Bill Evans could make this tune wistful, aspirational, dream-like. I bet Jones is feeling it too, coming in double time on a closed hi-hat, then on the snare. Is Philly Joe imitating the train taking us to California? Sticks on the second chorus, the music opens up, his cymbal playing is saying to Bill: “Go ahead Bill, I got you.”

“Polka Dots And Moonbeams”. Jones’s entrance on the melody with Evans is a giveaway: Evans had a book as complete and detailed as a big band, and Philly Joe knows every note. Jones keeps the energy up, and is projecting his own feelings without ever pulling focus from Evans, the trio, or the composition.

For Evans, Gomez, and Jones, these arrangements and repertoire speak loudly: this is no jam session, this is a presentation, and we are a trio.

“Turn Out The Stars”. No time to get maudlin, Philly Joe grabs the sticks and starts kicking butt in the 2nd chorus, varying his ride cymbal rhythm and marking the bridge with triplets in groups of four on the rim and cymbal.

“Stella By Starlight”. A bright tempo, and Jones plays a truly strange polyrhythm at the end of Gomez’s first B section. I’m savoring the details: the sustain of the open hi hats, the gentle bass drum hooking up with Bill’s left hand, Jones’s subtle texture and density changes, his high intensity at a very low volume….

“You’re Gonna Hear From Me.” Written by Andre Previn, this tune was a recent hit for Andy Williams. We get one of those mysterious jazz unisons at 2:37, when Jones plays a fragment of Evans’ line with him on the bell of his ride cymbal. These brief confluences or unisons simply show how together Evans and Jones are; I’m sure there are a dozen or more all over this album, if not on this very tune.

“In A Sentimental Mood”. Almost the same tempo, but a different feel, and really, what’s wrong with the same tempo? The Bill Evans Big Band opens up on the 2nd chorus, and Philly Joe gets a great lick in at 1:09, almost the same rhythm as the miracle on “You’re Gonna Hear From Me”. Evans’ presentation of the melody is very arranged; notice how detailed Jones is on the bridge, catching every nuance Bill suggests.

“G Waltz”. The first brushes-only tune on the album, and I am almost lost in Jones’s unfussy beauty with them. This might be a rare example of Philly Joe playing something besides 4/4. He’s at ease, occasionally phrasing in 6/4 (playing the hi hat on 2, 4, 6). Amazing how natural a fit Jones is with Eddie Gomez.

“On Green Dolphin Street”. The first melody is the most open, Standards Trio-like texture yet, but when the solos start, Jones is authoritative, driving straight ahead. Strong, yet buoyant and nimble, Philly Joe is a perfect collaborator. Once again, on the out head he nails a very detailed Evans arrangement.

“Gone With The Wind.” Maybe the Philly Joe highlight of the album. His two feel on the first piano chorus is ideal, and over the next two choruses, he’s an ultra-modernist, even using his left foot as a comping voice (2:04). Great trades between Jones and Evans, then an absolutely classic Jones solo chorus:

He starts his solo with the melody of the tune, before working his signature phrases in and building through the chorus. Rudiments, bebop architecture, showbiz slickness, humor, and a reaching out, connecting with the listener. The feeling is so relaxed and casual as to belie his technical and conceptual achievement. “Oh this little thing? I’ll play that, sure, let me just turn it around, like a leaf that has blown away…” Jazz is filled with moments like this, tossed off bits of brilliance, easy to ignore, gone with the wind if you miss it.

“If You Could See Me Now.” Tadd Dameron is Philly Joe’s wheelhouse, and Evans supplies a great setting. Notice the melody paraphrase on the offbeats in the last A! Philly makes the ballads exciting, the burners controlled and focussed, and Bill is always the main event. Evans is on fire here, some of those double time runs in the second A of his solo are blinding.

“Alfie”. Like “You’re Gonna Hear From Me”, “Alfie” was current pop music in 1967. You hear a song on the radio, the melody sticks with you, then you see a singer do it on TV, and later that week, you hear it at a jazz club. No big deal. Philly lays out until a beautiful, dramatic cymbal roll in the middle of the bridge. Magic.

“Very Early”. Great example of broken-time from Philly Joe and Gomez. Jones’s ride cymbal playing is a complete piece of music.

“Round Midnight”. Evans includes the Gil Evans/Miles transition from the melody to the solos. Jones’s press roll is sublime, and I am reminded that Jones originated the drum part for this arrangement.

“Emily”. Philly is keeping the energy up. Evans could be languid, but Jones will not let him slide into sentimentality.

“Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams”. Here it is. Eight perfect bars of pure Philly Joe bebop with brushes. Evans is evidently delighted. They really open up and swing in the 2nd chorus, Philly Joe just keeps holding it down. Some great trading with Jones adding to and subtracting from his signature phrases — eights, fours, twos, ones! What a beautiful drum sound.

The night’s wrapping up, I pay for my drink and say hello to all the drummers sitting near me, hanging out and getting our drum lesson.

All respect and gratitude to Philly Joe Jones.

That’s how Art Blakey described him to Art Taylor in Notes And Tones— a natural actor.

Jones was always very clear that his teacher was Cozy Cole; his contact with Wilcoxon was limited to a few lessons.

Comedian Lenny Bruce, one of the main change agents of pop culture in the Fifties and Sixties, was a friend of Jones; Jones’s ‘Bebop Vampire’ was common property between Jones and Bruce.

thanks vinnie.. for anyone who wants to take a deeper dive into philly joes drumming, joerg eckel published a transcribed book of his work - the philly joe jones solo book..

https://www.practicingdrummer.com/philly-joe-jones-solo-book/

Thanks for homing in on Evans’ California Here I Come album. Great PJJ and not referred to too often. I had the wonderful if somewhat bizarre experience of witnessing him with Bill Evans at Newport Jazz Festival at Ayresome Park (football stadium) Middlesbrough U.K. in July, 1978. The audience was separated from the performers by the width of the pitch, so the exact opposite to your imagined Village Vanguard experience but totally unforgettable.