At one time, if you heard drums on a record, it was a human being playing them. Two new books show the depth of the lives behind some beloved music.

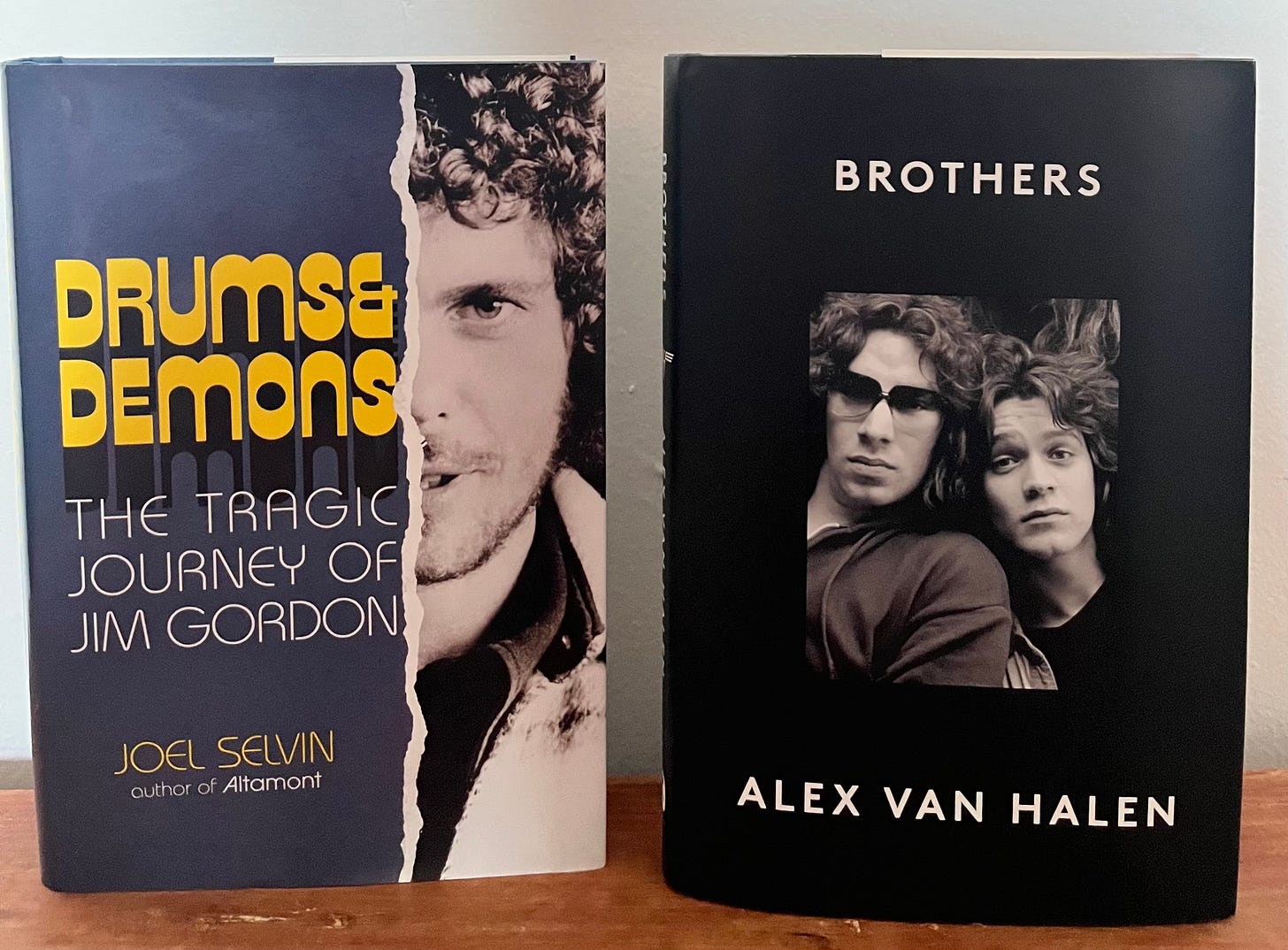

Joel Selvin, from Berkley, CA, has been writing about music since the late Sixties, most notably for the San Francisco Chronicle. His latest is Drums and Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon (Diversion Books, 2024), a thorough and respectful birth-to-death chronicle of the West Coast studio and rock drummer. The demons of the title refer, of course, to Gordon’s paranoid schizophrenia, which eventually compelled him to commit matricide in 1983.

As mental health discourse evolves, the need to know Jim Gordon’s story takes on urgency. I’m glad Selvin wrote this book.

James Beck Gordon was born in 1945 and grew up in Los Angeles. Spotted as a prodigious talent in his early teens, he hit the road with the Everly Brothers in 1963. By 1965, Gordon was an apprentice studio drummer, playing alongside Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer on Phil Spector and Beach Boys sessions, appearing on hits by Lee Hazelwood, Bobby Darin, Lou Rawls, and others. That’s Jim on guitarist Mason Williams’s proto-New Age instrumental hit “Classical Gas”, released in 1968. Glen Campbell’s immortal “Wichita Lineman” from 1969 goes up a notch when Gordon switches from brushes to sticks during the instrumental fadeout.

Selvin notes that in 1969, as “Wichita Lineman” was climbing the charts, guitar-based rock music (the Who, Zeppelin, Cream, Grateful Dead, etc) was most popular as a concert attraction, less so on records and radio. This is a subtle and helpful point. It’s why the easiest way to get a sense of that era scene are concert movies— D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop (shot in 1967, released 1968) and Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock (shot in 1969, released 1970). You had to see these bands.

The bug bit studio veteran Jim Gordon, who left the LA studio scene to go to England with Delaney and Bonnie in late ’69. Eric Clapton joined them overseas, cutting Delaney and Bonnie On Tour With Eric Clapton at the end of the year. Now based in London, Gordon embarked on a few years of dizzying activity with the British rock aristocracy as the Delaney and Bonnie rhythm section— Clapton, Gordon, bassist Carl Radle, and pianist Bobby Whitlock— became Derek and the Dominos. In addition to their sole studio release, Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs (Atco, 1970), the Dominos played on big portions of George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass and on all of Clapton’s first, pre-Layla solo album (the one with “After Midnight” and “Let It Rain”). Tying it all together, Radle and Gordon also toured with Joe Cocker. That’s Jim Gordon and Jim Keltner on Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen, one of the defining moments of the era, if little remembered today.

Sadly, as Gordon was reaching a pinnacle of his career, the first real cracks in his psyche were surfacing. Bandmates noticed some erratic behavior from Jim, even occasionally talking to himself, but Selvin recounts a violent encounter between Gordon and his girlfriend, singer Rita Coolidge, that is both shocking and portends darkly. It’s Coolidge who is at least the co-composer of the instrumental coda to Eric Clapton’s “Layla”, if not the sole composer, despite Gordon’s songwriting credit.

When his English adventures wound down in 1971, Jim Gordon returned to LA and resumed his studio career, punctuated by occasional tours. There are plenty of highlights: The Incredible Bongo Band’s “Apache”, a foundational hip-hop sample, Frank Zappa’s Grand/Petit Wazoo tour; Steely Dan’s Pretzel Logic (the one with “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number”) and “Rainbow Connection”, composed by Paul Williams and Kenneth Ascher, from The Muppet Movie soundtrack.

The unfussy details Gordon brings to “Rainbow Connection”, a universally-beloved piece of music, sum up his musicianship. Without pulling focus from the vocal, staying within the emotion of the song, Gordon’s energetic and tasteful tomtom fills, rim clicks (which he varies throughout), and propulsive time feel elevate the song. He’s playing his heart out. Without such a great performance from Jim, would we love this song the way we do?

“Rainbow Connection”, from 1979, seems to be a last hurrah for Gordon. Soon, Jim was working only sporadically, now too unreliable for high-profile studio sessions. Selvin tracks both Gordon’s growing isolation from friends and family in this period, and Jim’s serious efforts to silence the voices in his head, including rehab, prescription drugs, and psychotherapy.

Drums and Demons is most effecting when chronicling the final act of Gordon’s life, a tragic and horrifying tale which no explanation or context can soften. In 1983, no longer touring or recording, though playing locally in LA, Gordon’s paranoid delusions drove him to murder his mother. After the crime, he immediately turned himself over to the police, was tried, found to be schizophrenic, and spent the rest of his life incarcerated. He never played music again, and died in prison in January 2023.

Jim Gordon’s version of Black American folkloric drumming undergirds a big chunk of music from the Sixties and Seventies, and despite the destruction he wrought, his very beat feels life-affirming and positive. Selvin hears this painful contradiction, and writes with a deep respect and sympathy for his subject; his biography, plus NYC drummer Adam Minkoff’s jimgordondiscography.blogspot.com, an incredible resource, go a long way to helping us both appreciate Gordon’s contribution and, as Questlove says, “bring Gordon’s darkness into the light”.

Drums and Demons comes with the blessing of Gordon’s sole offspring, daughter Amy Gordon, and producer/composer Mike Post, who’d known Jim since childhood. The only way to conclude such a mournful story is with a quote that Selvin provides from Amy:

“I wish to remember him as the father who loved me and fought as hard as he could so that I might feel this above all the rest.”

To which we might add: we remember the selfless and gifted musician, who fought as hard as he could to share the best parts of himself with the world, that we might hear this above the tragedy, the brilliance of Jim Gordon. Amen and godspeed.

I first heard Jim Gordon on “Layla”, same as everybody. It was a staple of 96.9 WOUR, “the rock of Central New York”. WOUR’s other tag line was “classic rock AND quality new rock”. With such a moniker, every time there was a new Van Halen album, you knew they would spin it.

I dug Alex Van Halen’s sound and feel, but I didn’t take Van Halen seriously, had no awareness of their status in the culture, didn’t know they defined an era as fully as Madonna, Prince, and Michael Jackson. But for some reason when Geoff Kraly suggested I read Alex Van Halen’s book, I took it as an assignment.

Rock memoirs are often myth making and score-settling, but Alex Van Halen’s Brothers (Harper, 2024) is neither. Composed solely by Alex, without a ghost writer or co-author with assistance by famed New Yorker staff writer Ariel Levy, Brothers is a beautifully-written memoir and elegiac tribute to Alex’s brother, guitarist Edward Van Halen, who died in 2020. We’re very lucky to have this book.

Everything in music becomes more interesting when you get a little closer. I learned a lot from Brothers:

I’d known that Ed (as Alex calls him) and Alex were born in Holland and that their father, Jan Van Halen, was an accomplished musician, but I didn’t know their mother, Eugenia (called Ottie), was Indonesian, or that Indonesia had been a Dutch colony! The dark legacies of racism and colonialism are still being played out. I am learning, I am learning.

When the Van Halens moved from Europe to the US— from Holland to California— Alex and Eddie were 8 and 6 years old, spoke no English, and lived with their parents in a single room in a house shared with three other families while mom and dad searched for work. The success of Van Halen was the fulfillment of the American Dream, what their parents hoped for when they uprooted their lives and came to the new world.

Alex Van Halen epitomized the stadium rock drummer— setting his gong on fire, multiple bass drums, et cetera. His photos in Modern Drummer were unforgettable. So I was surprised to learn that once his family had some stability, the wild rocker spent much of his youth seriously pursuing piano, violin, and saxophone.

When rock arrived in 1964 with the Beatles and the Dave Clark Five, it wasn’t the drums that enchanted Alex: he bought a guitar, while Ed paid for a drumset with a paper route. That’s right— originally, Alex was the guitarist, Eddie was the drummer.

(The Dave Clark Five connection is interesting. The characteristic Van Halen rhythm is a flattened out, big-hair version of the boogie-woogie, eight pumping eighth notes to a bar. “Jump”, “Panama”, “You Really Got Me”— it’s Black music all the way down. Listen to Dave Clark Five’s “Glad All Over”, and it’s easy to hear the seeds of the Van Halen boogie in Dave Clark’s march.)

Because Brothers is focussed on his life with Ed, Alex doesn’t share much drum lore, but what he offers is telling. Like all drummers who came of age in the Sixties, the first thing Alex learned was big band swing, which he played on dance gigs with his dad.

Here’s Alex on the drummer in his father’s band:

“A guy named Max— typical drummer, always a glint in his eye, everything done a little tongue in cheek…he taught me this thing called pannenkoeken, which is just Dutch for pancakes: a double-stroke roll…I was so taken by his vibe. We stayed in touch until his death three years ago.”

Typical drummer! You can finish Brothers in two or three long subway rides, so naturally do the sentences flow. Bravo, Alex Van Halen and Ariel Levy.

Unsurprisingly, it’s Ginger Baker, Keith Moon, and John Bonham who Van Halen patterns himself after, with a big shoutout to Hal Blaine. As a double bass drum devotee, he makes special room for Louis Bellson, Ed Shaughnessy, and Billy Cobham.

But famous drummers and British bands are secondary to Alex’s brother and father. That’s where the juice is. Though alcohol was a problem for father and sons, Jan Van Halen was profoundly supportive and available to his kids, such that Alex, with the benefit of hindsight, sees his band as a tribute to his pops, an application of everything Jan had taught Alex and Ed about the power of music.

Brothers showed me that Van Halen’s music is the expression of a bond between two brothers and their father. Music was the family business. It would be disrespectful to the band and their fans for me to say I completely get Van Halen, but I’m in awe of their achievement— they sound like absolutely no one else, now or then. Respect and gratitude.

The profound love and trust Alex and Ed shared enabled them to be fully themselves. That’s why their band was so different. This is their contribution, this is what we’re hearing, and this is what Brothers is all about.

Thanks to these wonderful books, I’m newly aware of the complexity and humanity in some songs I first heard during the Reagan Administration. In 2025, I will continue to take all music and all musicians seriously. Music is humans at our best. Where would we be without it?

Happy New Year everyone! I’m so honored to be writing for you.

Great stuff. My favorite Jim Gordon session is probably Richard “Groove” Holmes’s SIX MILLION DOLLAR MAN. Gordon + Chuck Rainey + arrangements by Oliver Nelson, what a record.

i read the rita coolidge book, so i knew of the story as she told it in her autobiography... thanks for the notes vinnie! happy new year 2025 - i hope it is a healthy and happy one for you!