Chapter One drops on Monday

I'll be writing furiously til the last minute.

“How the drumset came to be” in bullet-point chronology:

1882: Chicago-area theater and rudimental drummer Arthur Rackett mail-orders a bass drum pedal from “Dale of Brooklyn” (probably instrument maker Benjamin B. Dale1) thereby starting a bass drum pedal trend in Chicago. No photo has yet emerged of Rackett’s pedal.

1896: New Orleans bandleader John Robichaux’s band is photographed. Drummer Dee Dee Chandler casually displays his homemade bass drum pedal, the earliest known hard evidence of such.

1909: Chicago drum store proprietor, timpanist, rudimental, and theater drummer Willam F. Ludwig manufactures a popular and reliable bass drum pedal, the basic design of which is still in use today. His success with the pedal leads to the Ludwig Drum Company, soon selling complete drumsets with bass, snare, cymbals, Chinese-style tom-toms, woodblocks, cowbells, etc.

1925: “Snowshoe”cymbal pedals2 arrive, per Chicago drummer Vic Berton’s patent.

1927: The low-boy and hi-hat are introduced, at the very same time, in the very same catalog, as the “cymballum” and “universal cymballum” respectively, manufactured by Walberg and Auge in Worcester, MA.

There we have it, an accurate, optimized, just-the-facts, short-short-short version of how we developed the drumset, an endeavor of just 45 years.

But wow does it leave me flat. It’s just a complacent, boring list of events and dates, as the camera moves in for a close-ups on photos of well-dressed men holding things as the ricky-ticky music plays.

I stare at this list of dates and sense another, wild story: how in 45 years, guided by no primary author, a new way of playing and thinking about drums, the world’s second-oldest instrument, became a part of our shared heritage.

I want to know why Baby Dodds, for instance, embraced and accelerated the new sounds from Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong, or what Zutty Singleton did that made him Earl Hines’s and Louis Armstrong’s choice for a co-operative band, or what pushed Gene Krupa to study Baby Dodds, or what Krupa saw and heard when he encountered Chick Webb that so fired his imagination, or how and why Chick Webb thought he could be a premier jazz bandleader in Harlem, at a time when that occupation barely existed.

A fool’s errand to try to get to the heart of this, but that’s where I’m at.

Tech people talk ‘empowerment’, ‘enhancing the experience of being human’. It’s PR blather, and we know it. What tech people want is for us to use a thing and then forget how we lived without that thing, thereby enriching them.

Yet no tech company would invent a drumset. Tech-like thinking wouldn’t bring it about either, for it wasn’t invented by tech’s grandfathers— inventors, manufacturers, 20th century titans of industry. The drumset was invented by drummers3, because they needed it, for reasons economic, musical, and spiritual.

Unlike the drumset, digital tech seldom becomes a beloved part of culture, because anxious, data-driven, comparative pursuit of perfect return on investment is soul-destroying.

For instance, I’ve yet to meet a musician or engineer who actually cares about ProTools— in fact the bland, gray t-shirt name “ProTools” tells you how little we care about it. Studer and Ampex tape recorders with a Neve console— now that’s something we get excited about. Between takes, we sit on the couch in the control room and search for images of vintage gear, then we pass the pictures around, everyone agog. In fact, the more expensive the studio I’m in, the more non-digital recording gear it uses.

The drumset is not optimized drumming— as the masters showed us, it’s a brand-new, hot-rod vessel for ancient wisdom. Ancient to modern. That’s why we love it and those who play it. So no optimized list of dates and important figures will do. Talk of jazz drumming and history is no occasion for blandness.

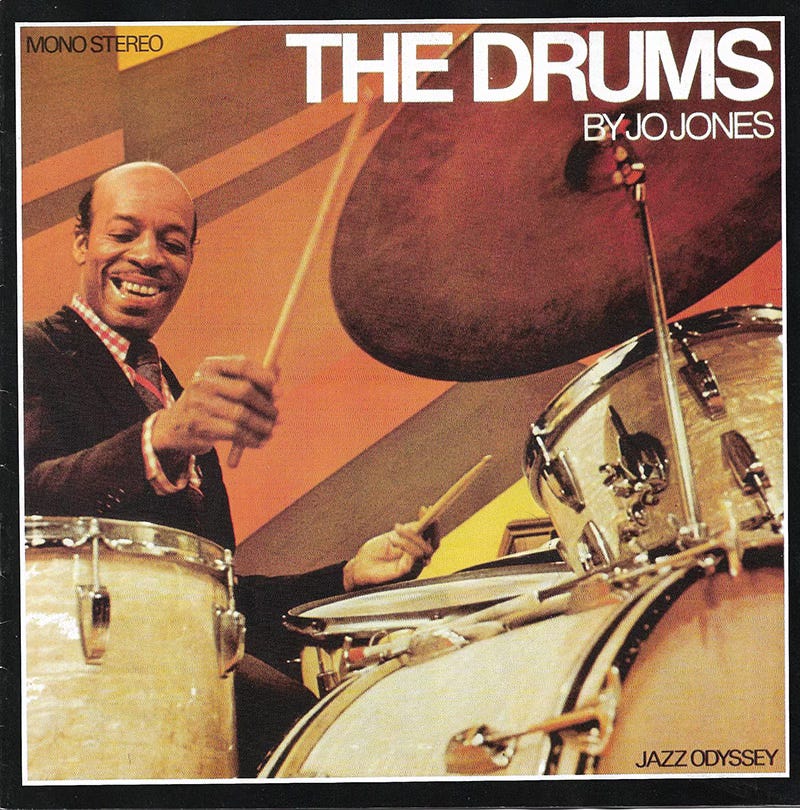

Ding-ding-a-ding on a cymbal, woodblock, or similar had been going for years before Jo Jones swung the hi-hat on “Lady Be Good” with Walter Page, Count Basie, Lester Young, and Carl Smith in 1936.

Jones’s message was less what he did and more how he did it, musically and emotionally. In Jo Jones, a basic and common ragtime-derived pattern became dramatic poetry and personal expression. By 1936, jazz drummers were specializing in a continuo part, and some played it on a hi-hat years before Jo Jones. But only Jo Jones did it that way. He made that thing his, it was beautiful, and we’ve never gotten over it.

That’s the point, that’s the magic, that’s the story I’m trying to tell. Chapter One (mostly pre-history) drops Monday. See you then.

1882, as the brilliant scholar of drumset history Paul Archibald says, “does seem remarkably early” for a mail-order bass drum pedal, though Archibald’s University of Edinburgh colleague Matt Brennan in Kick It (Oxford, 2020) seems to accept Rackett’s testimony, perhaps with a slight reservation.

So called because they’re big and flat and look sort of like a snowshoe.

William F. Ludwig Sr. made his 1909 bass drum pedal in a factory because he couldn’t keep up with demand for his homemade design. He didn’t dream up the pedal, find investors, and then try to put those who didn’t need or want it out of business!

Hi Vinnie, have you read Kick It: A Social History of the Drum Kit, authored by Matt Brennan - it’s great. Some good drummer jokes too, I found it to be really interesting

So looking forward to this! Zutty is my guy. In my dissertation, “The Evolution of the Ride Cymbal Pattern from 1917-1941: An Historical and Critical Analysis” I posit that bandleaders had a direct influence on how drummers orchestrated tunes and how eventually that drove the pattern to take over the music. Excited to read your work! Congrats!