Chasin' The Bird: Clifford Jarvis

Recognizing an important player who connected disparate scenes.

Two pianists, two worldviews, one drummer:

One pianist is wearing colorful, flowing robes, surrounded by a big band. Lights are flashing, dancers are on stage, the huge auditorium is sold out. A swinging, almost-conventional jazz melody spirals off into a pan-African vamp, which in turn becomes a vocal chant, then a percussion solo, and finally a totally improvised piano solo: vaudeville, storefront church services, Duke Ellington, and bebop are coexisting on stage.

The pianist behind all this sits taciturnly, unquestionably the leader but unconcerned with micromanaging the night. The trappings of showbiz the pianist uses— the costumes, dancers, lights, and routines— are grafted on a bed of deep musicianship and a world-shattering belief in himself, his mission, and his people. The music is, ultimately, authentic, correct, and true; its audacity shows us the limits of our imagination. It is what real freedom might sound like.

This is a partial view of Sun Ra. He can only be rendered in part, never in total.

Across town, another pianist is teaching a class. Anyone can attend— all a student needs is $10 and an open schedule. Seated at the piano, he’s surrounded not by a big band, but by a motley group of acolytes, hanging on every word he utters. He’s holding court; there’s not much dialogue between teacher and students. His references are obscure— ancient pop songs, composers, beboppers, and vocalists— and it’s not obvious where the class is headed, what final point or proof he’s driving at. The pianist/teacher’s speech and questions seem to have a momentum of their own.

But listen to his music: the scale fragments become bits of melody, bits of melody become songs, and finally, when the songs open up their mysteries, you are in the presence of uncompromising beauty and pure human aspiration. It all comes from the pianist’s generosity, his impulse to share knowledge, disseminate wisdom, to help as he can. He wants you to hear the truth.

We know who this is. It could only be Barry Harris.

Sun Ra and Barry Harris might represent divergent ways of doing jazz— one outward toward society, reaching everyone, one inward towards purer music, discovering the soul of harmony, rhythm, melody. But the music of Sun Ra and Barry Harris is more akin than I realized, for they share a drummer: Clifford Jarvis.

When Clifford Jarvis’s name is mentioned, it’s often in connection to Tony Williams1, a musician so important that calling him one of the most influential jazz drummers of all time barely scratches the surface.

But it’s a mistake to hear Jarvis as I did— as a precursor to or influence on Williams. Clifford Jarvis is a great and important musician, regardless of his connection to Williams, or Alan Dawson, with whom both Jarvis and Williams studied, and the Boston jazz scene.

One of the most accomplished players of his era, the mature Clifford Jarvis had a top-of-the-beat time feel and had a singular talent for creating polyrhythms with the different parts of the drumset. He was a brash, brilliant master who seemed to say “precedent be damned, I’m playing a bass drum/snare drum 3:2 polyrhythm right now!” even when playing with Barry Harris. His sound was high-pitched, and his touch was precise, which meant that each time he played one of his polyrhythmic ideas, it amounted to a mini drum solo.

This made the early, mature Jarvis a harbinger of Sixties drumming: the sound of civil rights marches and protests, of freedom: active, strong, virtuosic, exciting. By the late Sixties, when Jarvis was mostly heard with Sun Ra, he would play the entire history of jazz drumming in one concert, everything from marches and Dixieland to cacophonous ‘multi-directional’ improvisations.

However, his genius is clearly heard between August 1962 and January 1963, when he recorded with both Barry Harris and Sun Ra. To be the perfect drummer for both pianists requires a unique mind and a rare openness. Only a master jazz musician could unite such differing experiences, find the truth beneath the surface details.

I’ve yet to find one interview with him, or even an interview where he’s discussed in detail. Yet all of the Sixties jazz ideas crossed Clifford Jarvis’s desk: we can’t have a complete discussion about that time without including his contribution.

Clifford Jarvis was born August 26, 1941 and grew up in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, immersed in jazz2. He made his recording debut with Chet Baker3 in 1959, at age 17. By age 18, he had recorded with Randy Weston, Yusef Lateef, and played on Freddie Hubbard’s first Blue Note leader date, Open Sesame (Blue Note, 1960).

Teenage Jarvis sounds good on Open Sesame, focussed on swinging and driving the band. He’s not yet a wise player; his literal phrasing occasionally runs afoul of bassist Sam Jones and McCoy Tyner on piano, both of whom know a thing or two about creating a wide, buoyant feel. No matter; Jarvis was on the scene, improving every minute.

Barry Harris left his native Detroit in 1959 to join Cannonball Adderley’s quintet in NYC. He made an immediate impact, and by 1960 was recording for Orrin Keepnews at Riverside.

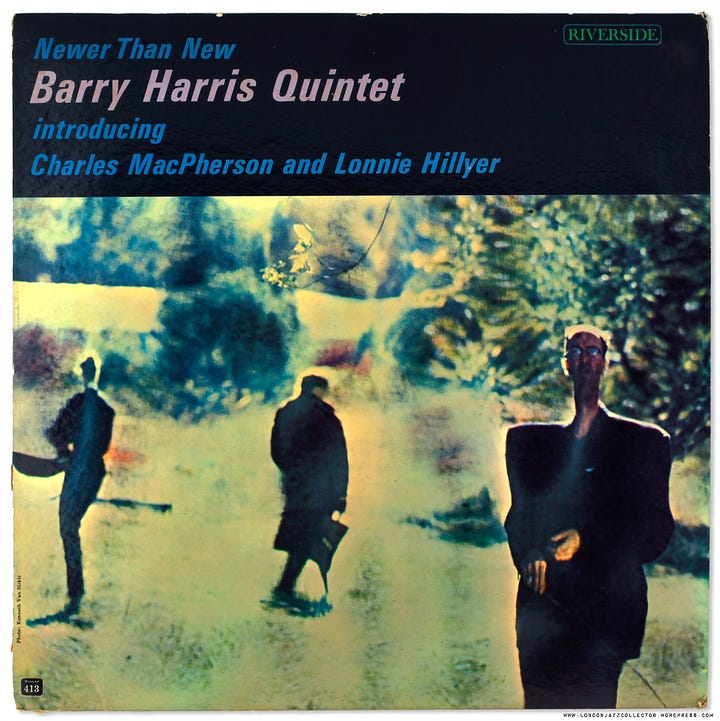

Harris enlisted Jarvis to join him, alto saxophonist Charles McPherson, trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer, and bassist Ernie Farrow to record Newer Than New (Riverside, 1961) On “Easy To Love”, Jarvis is right at home with the medium-up tempo, and has taken a giant step forward since Open Sesame. He deploys some Max Roach or Roy Haynes bombs at the cadences, but there’s something almost transgressive about the way he breaks up the cymbal rhythm. Are drummers allowed to play like that in a bebop quintet?

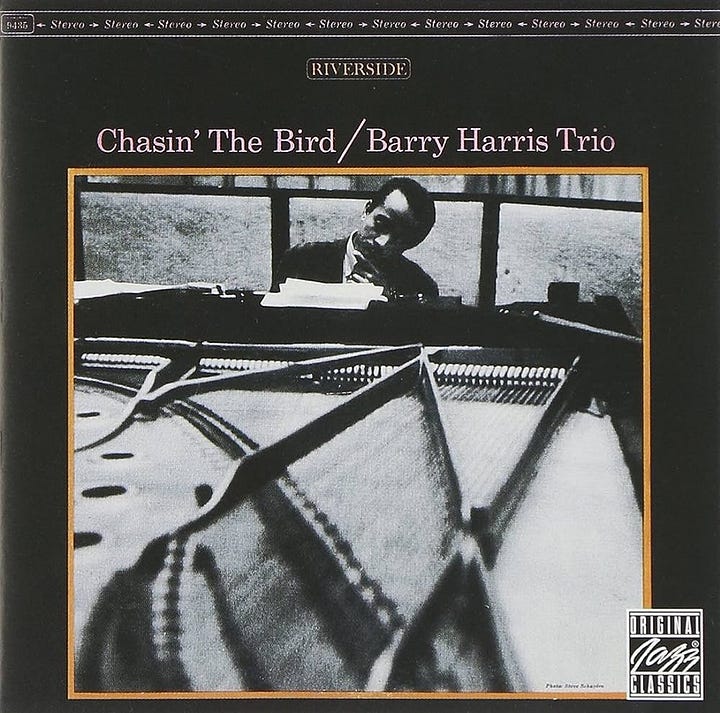

A year later, Barry Harris recorded the trio date Chasin’ The Bird (Riverside, 1962) with Jarvis and bassist Bob Cranshaw. Jarvis’s conception has crystallized, matured and deepened. Jarvis now has his own version of the bebop language of Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, Shelly Manne, and so on. Basically, he follows the rules— cadential points of the song for the most activity, clave fragments during the solos, outlining the form of the song— but thrillingly steps outside the bounds once in a while.

His elegant, nimble cymbal beat supports Harris’s first chorus of “Chasin’ The Bird”, but by the second bridge, dense snarls of bass drum and snare drum have put us on notice. There are now hints of avant-garde energy around the edges of his virtuosity, as well as a much deeper understanding of swing and groove.

On “The Breeze and I”, Jarvis turns a nice Afro-Cuban vamp into an unsettled, active space, subtly altering his patterns and refusing to let things become too secure. Jarvis’s virtuosity is on display on “Around The Corner”, aggressively accenting on the bass drum in a hip, contemporary way. When I listen to this, I think “I should do that on the next gig I play.”

“Indiana” is the way-up burner, and Jarvis is fully in command, playing softly, with the correct Max Roach accents. But “Bish Bash Bosh” is, for me, the Jarvis masterpiece of the album, simply for the way he plays the head. Here, Jarvis plays the hiccuping melody on the drums, and masterfully catches every nuance of the head. Perfect!

Chasin’ The Bird is one of the great piano trio albums, and Jarvis’s playing on this album should have put him in the jazz drum history books. He was just 20 years old, had never set foot in a conservatory, and if he played like this tonight at Mezzrow, he’d be the hippest drummer in NYC. All respect4.

Sun Ra and the Arkestra arrived in NYC that spring, and Ra immediately made things happen. First he arranged for rehearsal space at a dance studio, continuing his lifelong habit of lengthy daily full-band rehearsals5.

Jarvis was playing with Sun Ra and a small group of Arkestra members in late 1962 or early ‘63 when four of Ra’s arrangements of standards were taped at the “Choreographer’s Workshop”:

“Time After Time”

“Easy To Love”

“Sunny Side Up”

“But Not For Me”

To hear just how far ahead Clifford Jarvis was, listen no further6.

All four tracks are at almost the same tempo, a medium-up I associate with Tony Williams and Ron Carter with Miles Davis; the vibe between John Gilmore and Clifford Jarvis feels just like Williams with Wayne Shorter and Sam Rivers.

Of course, I’m hearing this backwards— in 1962, Tony with Wayne or Sam Rivers was in the future in 1962! Either Tony got it from Jarvis, or both Williams and Jarvis were playing ‘Roxbury drums’, the hometown style. The point is clear, however: we are hearing drum folklore, the sound of a community, from both Williams and Jarvis.

On “Time After Time”, Jarvis, like Roy Haynes, is playing a ‘rolling eighth-note’, using an almost-straight 8th note as the basis for polyrhythmic exploration. Jarvis on the last A of the trumpet solo is WHAT!

Ra’s arrangement of Cole Porter’s “Easy To Love” is, like “Time After Time” enough to convince any Ra holdouts. Tenor saxophonist John Gilmore and Jarvis are dialoging; the six-note snare/hi-hat combo from 1:17 to 1:21 is brilliant, Jarvis’s lick on the snare from 2:14 to 2:18 is outrageous, and there’s a miraculous jazz unison between Gilmore and Jarvis at 2:30.

“Sunny Side Up”, by DeSylva-Brown-Henderson, who also brought us “Bye Bye Blackbird”, is the most obscure tune on the session, and dates from 1929. Another magic arrangement, played by Gilmore and uncredited alto, Marshall Allen I assume. The tempo picks up slightly, and as Jarvis exchanges fusillades with Gilmore, we hear a sound that would soon become widespread.

George Gershwin’s “But Not For Me” starts with an 8 bar Sun Ra intro, where laconic swing-to-bop spirals into mystery and magic. Jarvis gives Ra plenty of space, letting him make his statement, and Ra in turn seems to have fully liberated Jarvis. His use of hi-hat/snare drum/bass drum combinations to propel the music and spur the soloists is unique, nowhere more than on this track.

Now the main Arkestra drummer, Jarvis appeared on most of Sun Ra’s recordings for the next 15 years. Sun Ra: The Complete Nothing Is (ESP), a live album recorded in May 1966, is worth its own essay, so far-reaching is Ra’s vision, and such a part of the tapestry of the Arkestra is Jarvis. He remained in Ra’s orbit, on and off, until at least 19837.

Upon leaving Ra’s universe for good, Jarvis traveled to England, where he taught and played, forming a connection with Chris McGregor and the Louis Moholo-Brotherhood of Breath scene. He apparently stopped performing in the Nineties due to illness8, and died in England in 1999, far under the radar of the US jazz press, and, probably, all but a few musicians.

There is still so much to learn and understand about his life and music. This brief essay is just a beginning. Please leave any info you have in the comments.

As always, all thanks and all respect to Clifford Jarvis.

Quick notes on other important Jarvis records:

Jackie McLean: Right Now! (Blue Note, 1965). Classic date, incredible Jarvis. On “Christels Time”, pianist Larry Willis and Jarvis follow the contour of McLean’s solo perfectly while outlining a challenging modal form.

Big John Patton: That Certain Feeling (Blue Note, 1968). Great organ session with Booker Ervin; Jarvis could be a stone-cold boogaloo drummer too. On “Daddy James”, only the hi-hat ideas give him away. Otherwise, he could be Idris Muhammad or Ben Dixon.

Bukky Leo Quartet: Evolution (Bandcamp, recorded 1987) Bukky Leo played saxophone in Nigerian drummer Tony Allan’s band. This recent release has some excellent later Jarvis. Try “Dubai” to hear how African influences were playing out for Jarvis in the Eighties.

Jarvis and Williams knew each other as youths (Williams was four years younger) in Boston, where both studied with Alan Dawson. They both made their debut on record at age 17, and both were charismatic virtuosos, ready to light the music on fire.

John Fordham’s informative and helpful obituary from The Guardian mentions that Jarvis’s father and grandfather are trumpet players. According to both Horacee Arnold and Billy Hart, Jarvis’s father was Malcolm “Shorty” Jarvis, an associate of Malcolm Little in, evidently, Harlem and Boston, before Malcolm Little became Malcolm X. More on this as the situation develops!

Chet Baker Plays The Best Of Lerner and Loewe (Riverside, 1959).

A widely-heard Jarvis performance is Freddie Hubbard’s Hub Tones (Blue Note, recorded October 1962). It’s a classic album, and I’m enjoying it as I type these words, but to me Jarvis sounds somewhat reined-in overall. Good as it is, it’s not a showcase for Jarvis at his best in 1962-63.

Often Ra would record these rehearsals, documenting everything for future release, stockpiling hours of unreleased music.

Ra fought for every note, every day; NYC was no different. It was years before the Arkestra began its Monday night residency at Slug’s in the East Village, and eventually the band moved to Philadelphia, where Marshall Allen still resides.

Sun Ra was so ahead of his time— Bandcamp is the best place to get his music, and he seemed to be recording with something like Bandcamp in mind in the Sixties.

All four tunes were released on a Nineties Sun Ra release called, simply, Standards (1201 Music). It’s a great album, includes a duo of Sun Ra and Wilbur Ware on the Tommy Dorsey ballad “Can This Be Love” from when Ra was known as Sonny Blount, and is streaming on all the major services. Sun Ra was the low-budget, high-innovation alternative to all the great jazz being released on Impulse, Atlantic, and Columbia at the time.

The only video I’ve found of Jarvis is a few frames in a Ra video from that year. But thanks to reader Tom Gsteiger, I’ve been alerted to two full-length Archie Shepp concerts from the late Seventies, featuring Jarvis: here’s 1978, and here’s 1977. (More on these later.)

The Lord Discography lists nothing of Jarvis after 1991, save a keyboard credit in 1995.

Great informative article again. Thanks. Re. Malcolm ‘Shorty’ Jarvis: he certainly was Clifford’s father and the associate of MalcolmX played in Spike Lee’s movie, ‘Malcolm X’, by Lee himself. Points of interest: 1. Malcolm ‘Shorty’ Jarvis, was not short and his nickname had nothing to do with his stature, ironically or otherwise. I’m sure Horacee Arnold and Billy Hart, who informed you of the connection to Clifford will know the origin of his nickname. 2. Tony Williams has referred to playing with Malcolm ‘Shorty’ Jarvis and to him being his father’s (Tillman) best friend.

This is awesome. I've loved Ra for years, but know little about his excellent band, besides Marshall Allen.