John Coltrane’s birthday was this past Saturday, September 23rd. There’s no end to John Coltrane’s music, no limit to its importance, or to our still-growing understanding of his music. What a message, what an achievement— John Coltrane’s music only makes things better!

When I think about Coltrane and his continuing centrality to jazz, my thoughts go to his community. As Coltrane always stated, he owed much to his mentors— first Dizzy Gillespie, then Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, and probably a dozen or more other names, folks known only to those truly in the circle.

Like Thelonious Monk, Coltrane was a family man, and his music was deeply connected to family life. The song titles alone tell the story: “Cousin Mary”, “Syeeda’s Song Flute”, “Naima”, “Wise One”, and others.

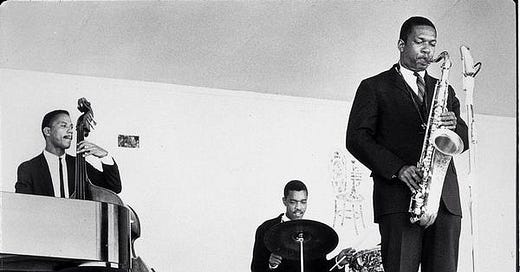

A man of uncompromising integrity, with the support of his family and community, Coltrane was able to assemble a large group of collaborators— pianists Steve Kuhn and McCoy Tyner, saxophonist Eric Dolphy, bassists Steve Davis, Art Davis, Reggie Workman, and Jimmy Garrison. The drummers who worked with Coltrane on his own music form a pantheon: Philly Joe Jones, Art Taylor, Jimmy Cobb, Pete LaRoca, culminating in Elvin Jones, and taken further still by Rashied Ali.

These are just some of the folks that helped John Coltrane get his message to us. Bravo, amen, and thank you John Coltrane!

For more and deeper thoughts on John Coltrane and his music, I recommend Substacks by Lewis Porter, Harmony Holiday, and Ethan Iverson.

This past Saturday, listening to Coltrane on his birthday, it dawned on me that at the beginning of his career as a bandleader, Coltrane recorded with two drummers who were closely tied to Ornette Coleman.

I had never thought about it, but in 1960, John Coltrane recorded with both Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins, the two players who forever defined the role of the drummer in Ornette’s music. Coltrane was well-known as an early and vociferous supporter of Coleman’s, so it stands to reason, but I was still struck by the observation: Coltrane didn’t just support Coleman’s music, he started playing with Coleman’s musicians right away.

Coltrane’s 1960 studio encounters with Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins weren’t widely heard then, and don’t seem well known now. Curious, as this is great Coltrane music with two of the most advanced drummers of the era, indeed, two of the greatest drummers of all time. It’s informative to hear Blackwell and Higgins with John Coltrane, and, more importantly, the music is a lot of fun.

The Blackwell-and-Higgins Coltrane albums also put Elvin Jones’ contribution in a new relief. Want to hear how truly revolutionary Elvin was? Notice how different Coltrane’s music sounds before Elvin Jones joined the band.

When Roy Haynes played with Coltrane in 1963, the character of the Coltrane Quartet was well established. When Blackwell and Higgins recorded with Coltrane, Elvin hadn’t yet made his mark with Coltrane— “Coltrane with Elvin” was still in the future.

Coltrane’s studio meeting with Ed Blackwell is available on all the streaming platforms as The Avant Garde, an Atlantic release for which both trumpeter Don Cherry and John Coltrane are credited as leaders.

The Avant Garde was recorded in two sessions, and Coltrane, Cherry, and Blackwell appear on all tracks. The first session featured Charlie Haden on bass, from which came “Cherryco” and “The Blessing”. On the three remaining tracks— “Focus On Sanity”, “The Invisible”, and “Bemsha Swing”— the bassist is Percy Heath, then of the Modern Jazz Quartet.

This is the first NYC recording session of Ed Blackwell, about whom I plan to write a great deal, as well as the earliest recording of Blackwell with Cherry and Haden, lifelong musical partners. There’s much to say about Blackwell’s drumming and music, but for now, we’ll just focus on “Cherryco”.

John Coltrane and Don Cherry, “Cherryco” (Don Cherry); John Coltrane, tenor; Don Cherry, trumpet, Charlie Haden, bass; Ed Blackwell, drums. Recorded June 28, 1960, NYC.

Blackwell uses his knowledge of street beats and Max Roach to create something startling and subtle on this track, especially behind Coltrane.

After the head, Cherry solos first, and Blackwell punctuates and comments with complete ideas, very much in the bebop tradition. When Coltrane steps out, Blackwell neither gets louder or softer, he just keeps the music at the same intensity.

Indeed, Blackwell’s insistence on one dynamic level, and his clear articulation of 4/4, rather than becoming monotonous, keeps the music moving forward, and provides a consistent backdrop for the solos. He seems to be saying, “this music is disciplined and intuitive”.

Moments into Coltrane’s solo, Blackwell turns off his snares, grabs a timpani mallet with his left hand, and comments melodically, using the whole kit to create a new color palette for Coltrane. Whereas Elvin Jones’ left hand and right foot sputtered, sighed, and roared in tandem with the emotional arc of the music, Ed remains independent, and creates little solo-ettes, detailed and engaging footnotes to Coltrane’s speech.

The stick/mallet combo is telling— Vernel Fournier used the same combination for “Poinciana”. . On this track, and on the album overall, Blackwell connects bebop wisdom to New Orleans parade beats, in an Ornette-derived open form. This became Blackwell’s thesis in general, and with Don Cherry and John Coltrane, it’s stated in something like a pure form.

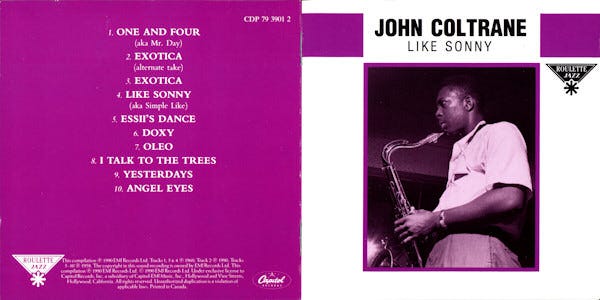

Coltrane hired Billy Higgins for a series of gigs in California in September 1960. One week into their two-week engagement at the Zebra Lounge, in Los Angeles, Coltrane took the group into the studio to record three titles for Roulette Records1: “One and Four” (eventually known as “Mr. Day”, from Coltrane Plays The Blues), “Exotica”, and “Like Sonny”.

As of today, only “One and Four” is streaming on YouTube and Apple Music. I’ll provide a description of the other titles2.

John Coltrane, “One and Four (a.k.a. Mr. Day)” (John Coltrane); John Coltrane, tenor sax; McCoy Tyner, piano; Steve Davis, bass; Billy Higgins, drums. Recorded Sept 8, 1960, Los Angeles, CA for Roulette Records.

Every drummer plays ding ding-a-ding on the ride cymbal, but no two drummers do it the same way. That simple pattern is our obsession, our preoccupation, our fingerprint. What we play on a ride cymbal behind a soloist is the essence of our musical identity. Our cymbal beat is our tell.

No one plays the cymbal beat like Billy Higgins. Higgins’ cymbal beat, so wide and inclusive, so open, suggests tap dancers, Brazil and Cuba, guitars, maracas, social dancing, and much more. It’s imbued with folk wisdom, defies accurate notation, requires masterful technique, and takes years to develop. Billy Higgins playing a cymbal is high modern art.

On “Mr. Day”, Higgins is meticulous and precise. He’s playing soft to medium-loud, and almost never takes his right hand off the ride cymbal. It’s wonderful to hear Higgins’ cymbal with John Coltrane and McCoy Tyner; here are three iconic, genre-defining musicians, blending their sounds. We’re so lucky to have this music!

On his solo, Coltrane is extroverted, loquacious, searching, fearless, and charismatic in the extreme. By comparison, Higgins is reserved, but he’s not playing defense, he’s not staying safe. Instead, he’s carving out his territory and sticking to his principles, and it works wonderfully.

Higgins, Tyner, and Davis set the groove and are quietly relentless for seven minutes. McCoy Tyner and Higgins especially are in strong agreement. Not a note of Tyner’s left hand conflicts or crosses Higgins’ comping; it all just sits together.

On “Mr. Day”, Higgins puts the Coltrane Quartet— or at least Coltrane and McCoy— into the same groove that jazz fans know from Billy’s many groups with pianist Cedar Walton. Coltrane is nearly all things to all people; listening to this, it’s easy to imagine Coltrane sitting in with Walton, Higgins, and bassist David Williams for the ultimate late set at the Vanguard.

The rest of the session, which doesn’t seem to be available on any of the streaming platforms, includes two takes of “Exotica”, a 64-bar AABA pedal-point/thirds-relationship Coltrane tune, where Tyner comps various clave fragments, Higgins plays in two while implying 4/4, while Davis pedals and plays clear.

Finally, they record “Like Sonny”, and dispense with the Latin feel after the first solo chorus. The quartet swings out, Coltrane takes off, Tyner and Davis settle in, and the trademark Billy Higgins groove is resplendent.

According to the Lord Discography, the three tracks were first released on a Roulette album called The Best of Birdland Vol. 1. Huh? Readers, and Lewis Porter, please explain!

I have a 1990 CD called Like Sonny, produced by Michael Cuscuna, which has the whole session with Higgins, plus a session that Coltrane did with tubist Ray Draper.

Excellent post, as always. I had no idea about the Roulette sessions with Higgins! There’s a RSD EP release from 2016 with four tracks available on Discogs I’ll have to grab. Higgins sounds always sounds so good--not being a drummer, it took me a while to appreciate him on the more straight ahead Blue Note titles.

thanks for pointing out the coltrane cd - for sonny... there is a youtube link for anyone who'd like to listen to it - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxpcNz1g81w

i especially liked the last 5 tracks with ray draper on tuba soloing.. one rarely hears that sort of thing today.... - the sound quality is pretty poor for listening to the drums, but track 2 you can hear how higgins approaches coltranes sound and writing from a different angle then elvin jones...