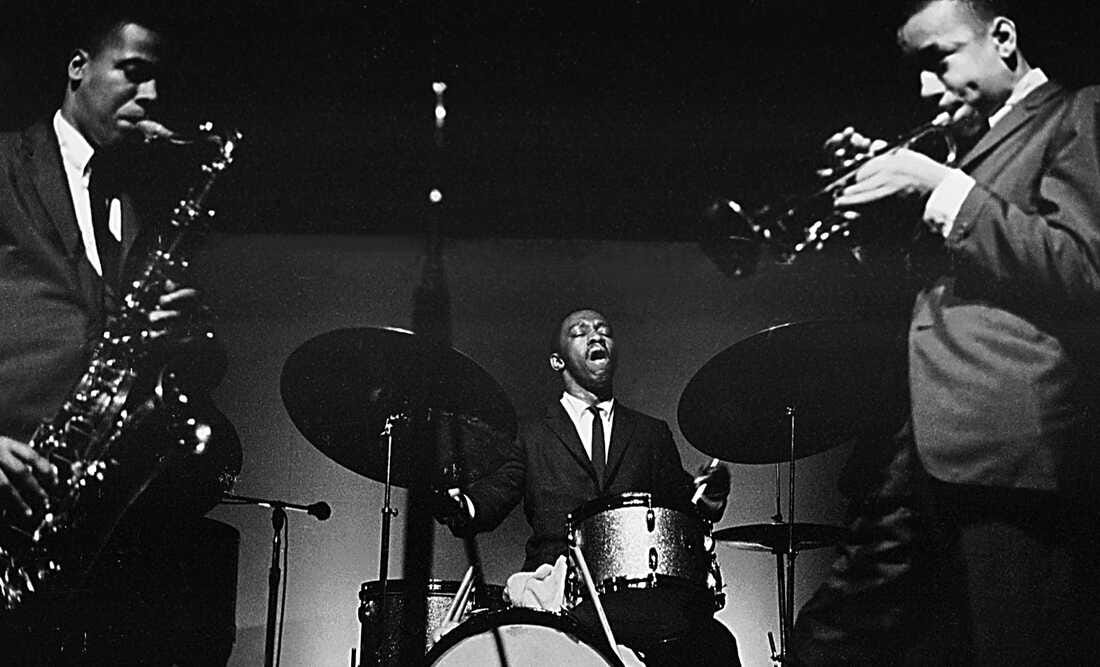

For Art Blakey and Wayne Shorter

Exploring the roots of Blakey's sound and his long kinship with Mr. Shorter

Wayne Shorter’s passing has brought an era to a close. Like you, I marked his absence by revisiting my favorite Wayne records, skipping around at first, and then settling into the albums Shorter made with Art Blakey.

It had been too long since I’d listened carefully to this music, and I was deeply moved by the classic Shorter/Blakey collaborations— there is so much beauty, humor, and humanity in this music. Mr. Shorter is as present and authoritative with Blakey in 1960 as he was with his own quartet throughout the 2000’s and 2010’s.

Throughout these records, Shorter’s genius amplifies Blakey’s uniqueness; Blakey’s many strengths, instincts, and tendencies spur Shorter to great heights. Shorter brought out the best in Blakey, and Art Blakey was as affected by Wayne Shorter as Miles Davis was, as Herbie Hancock was, as we all were.

Picking one example from many, Shorter’s “The Chess Players”, from The Big Beat, features Blakey’s idiom-defining, charismatic shuffle reframed and re-contextualized by Wayne’s music of the future, his perspicacious playing and composing. In fact, Blakey valued Wayne so much that he told Freddie Hubbard that Shorter was the star of the Jazz Messengers1. “The Chess Players” is in the vicinity of “Moanin”, but its very title is indicative of new possibilities, of a newly progressive era in the Jazz Messengers.

Art Blakey’s name has been synonymous with the hard-swinging, blues-oriented brand of modern jazz usually called ‘hard bop’ since 1959, when he recorded the aforementioned Bobby Timmons tune “Moanin” with trumpeter Lee Morgan, tenor saxophonist Benny Golson, pianist Bobby Timmons, and bassist Jymie Merritt. The impact of “Moanin” was huge— a hit record which opened doors for the band, took them around the world, and summed up their sound.

Great as “Moanin” is, it can fool listeners into thinking it’s the whole story of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers; that everything Blakey did with his band was an afterthought to “Moanin”, and that Blakey’s drumming can be summed up on that tune— a shuffle with a backbeat and a startling press roll.

No major figure in jazz can be summed up with one recording, no matter how great, and Art Blakey is a major figure. A closer listening— to Art’s playing, and the musicians he chose for the Messengers— reveals facets of Blakey’s music that hover just below the surface.

Blakey’s fully-developed voice was the result of many years of study and experience across many genres. His growth from a hard-charging big band drummer into the creative, fiery hard bop bandleader and mentor took place, in public, from roughly December 1944 (when, with Billy Eckstine, Blakey made his first recordings) to November 1959, when Wayne Shorter joined the Jazz Messengers. Every element of Blakey’s sound, style, and conception was added gradually, almost methodically, over a span of 15 years of professional music-making, years when Blakey played blues, recorded with R&B singers, studied African percussion choirs, and apprenticed with the heart core of modern jazz: Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker.

Blakey was always old school AND new school. In the 1940’s and 50’s, when he was playing with Monk, Bird, and Miles Davis, Blakey was combining the sensibility and vocabulary of pre-bebop drummers like Chick Webb, Sid Catlett, and Jo Jones with his own idiosyncratic approach; he did the same with Wayne Shorter, Woody Shaw, Wynton, and Terence Blanchard. Art Blakey was always playing something that was uniquely his own —a classic Blakey lick— and explicitly referencing pre-bebop drummers.

Blakey was always a deeply experimental player. Both as a drummer, and a bandleader, Blakey always went boldly where no one had gone before. With Thelonious Monk in 1947, he was exploring polyrhythms, four-way independence, turning the beat around, and dialoging with the band. As Billy Higgins said, “Art was Magellan.”— he went all the way around the world. With Blakey at the helm, The Jazz Messengers were all about blending and genre experiments, taking things from blues singers, R&B groups, and Latin music, and putting them in a bebop band. To go back to “Moanin”, it can be lost on modern listeners how out there it must have been at the time— there was essentially no precedent for placing a shuffle with a heavy backbeat at the center of a new modern jazz composition2 with long, virtuosic solos. “Moanin”, from this view, is avant-garde.

Seen in this light, Blakey and Wayne Shorter make perfect sense together. Like Blakey, Shorter was deeply aware of music outside jazz, and freely borrowed elements from across jazz— Shorter sounded a lot like Warne Marsh at the beginning of his career, composed “Lester Left Town” as a deeply reverent gesture to Lester Young, and showed a strong affinity for Brazilian music.

Blakey and Shorter were, in a sense, deeply akin, with perfectly compatible musical goals. Shorter and Blakey connected eras, reached audiences, and stayed true to their idiosyncratic selves, like all the great masters.

Respect and gratitude.

“Discipline means to relax….that’s what Chick Webb taught me. That’s the only teacher I ever had who taught me anything— him and Sid Catlett. When you listen to Chick on the last chorus of ‘Liza’, he’s beating the shit out of them drums; and I still use that lick to this day!

-Art Blakey, Modern Drummer, Sept. 1984

From the old school, no drummer was more important to Art Blakey than Chick Webb.

Webb’s career took off when he and his band began an extended engagement at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom in 1931, one of the first events to set the stage for Benny Goodman’s success; Webb, his drumming, and the dancers at the Savoy Ballroom were the seeds from which the entire Swing Era grew. In 1935, Webb began featuring Ella Fitzgerald, then a teenager, as the group’s singer; they had a hit record with “A-Tisket, A-Tasket” in 1938, still a part of pop culture today.

The B-side of “A-Tisket A-Tasket” was George Gershwin’s “Liza”, arranged by Benny Carter as a feature for Webb. Even a cursory listen to “Liza” shows how much Blakey internalized Webb’s sound, flash, and drive. I can even tell myself that this is a young Blakey playing, and my ears accept it, up to a point.

The first 8 bars of Webb’s solo, just snare drum and bass drum, are proto-Blakey, and I believe the accented triplets at 2:34-2:35 is the lick that Blakey used “to this day”. Webb still thrills, 85 years later.

Chick Webb certainly deserves his own essay!

Helpful as that knowledge is, it’s a long way from Chick Webb and “Liza” to Art Blakey and Wayne Shorter. Let’s go back to the beginning:

Art Blakey was born October 11, 1919; he was 40 years old in November 1959 when Wayne Shorter joined the band, and had been a professional jazz drummer and bandleader for over 20 years. Within those 20-plus years, Blakey had witnessed the music grow and change, from the era of territory bands and Black big bands to the rise of bebop, R&B, and the rapid expansion and fragmentation of jazz in the late 50’s.

At the beginning of his career, Art Blakey— five years younger than Kenny Clarke, five years older than Max Roach— struggled to fit into the ultra-modern, extra-hip Billy Eckstine Orchestra, which he joined in late 1944, drafted by Dizzy Gillespie to take over the drum chair from Shadow Wilson. This was the band that introduced Art Blakey to a wide audience, and Eckstine was as responsible as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie for bringing bebop to the masses in the 1940s. Blakey’s earliest small-group appearances on record, with Dexter Gordon, Fats Navarro , and Miles Davis are are all offshoots of the Eckstine band3.

With Eckstine and Company, Blakey played proud, sophisticated, grown-up Black music, launching his career and reaching a large audience. Just a few years later, in 1947, on his earliest recordings with Thelonious Monk, Blakey was an experimental master, advancing humanity’s capability with the High Priest, seeding whole universes of jazz.

In the Wayne Shorter era of the Jazz Messengers, Art Blakey found a way to do both things— reach a mass audience and advance humanity’s capability— consistently, which had probably been his goal, conscious or not, for decades.

Blakey’s music before the Jazz Messengers should be better known; it’s startling to hear his sound come together, element by element. Here are five great pre-Messengers Blakey tracks. I had so much fun selecting these tracks— this music is so great.

On Billy Eckstine’s The Jitney Man (1946), we hear bebop embedded in a big band; Eckstine’s “awreet” scatting, the Gene Ammons tenor solos, the Gillespie-ish trumpet solo from Kenny Dorham— all of this signified ‘bebop’ to their contemporary audience. Blakey’s drive and intensity are already unmistakeable, and his solo breaks are giveaways. Absent are the strong hi-hat, press rolls, and other Blakey signatures.

All of Thelonious Monk’s 1947 Blue Note music is, of course, essential, the cornerstone around which our moment is built, but “Well You Needn’t” in particular contains so many details, opens up so many doors. Here is Art Blakey the avant-garde experimentalist4.

Some details: At the third bar of Monk’s second A, Art turns the cymbal beat around, and begins phrasing in 3/4, up until the bridge; at the top of Monk’s second chorus, the 3/4 ideas continue. The Monk/Blakey unison at 1:44 is joyous magic; there’s a brief, ultra-hip triplet subdivision on bass drum at 1:57 coming out of the bridge.

Again, the ‘Blakey trademarks’ are not yet fully present, for the simple fact that they were added to his repertoire at a later date, to enhance music he hadn’t yet made. Respect to bassist Gene Ramey for his great playing and sympathetic openness to Monk and Blakey.

Lucky Millinder was a bandleader, not a performing musician. He was hugely popular in the late 40s and early 50s, and “Moanin The Blues” (RCA, 1949) with Art Blakey’s drumming way in the back of the mix, is a stand-in for many of his hits. I’ve included this just to show how well-traveled in American folkways Blakey was when he started shuffling and adding back beats to modern jazz.

Written and arranged by trombonist JJ Johnson for a group led by Miles Davis in 1953 featuring Johnson, tenor saxophonist Jimmy Heath, bassist Percy Heath, and pianist Gil Coggins, “Kelo” is a miniature masterpiece. The group is playing Art’s beat, and Art uses every trick he has to create an endless variety of texture and intensity. We’re really starting to hear “Art Blakey” on this track.

We get a pitch-bend on the snare, a press roll and crash behind Miles’ solo, then Afro-Cuban tom toms and tom/rim combinations behind Heath; the Chick Webb fireworks have been reduced to tasty snare drum solo-ettes. The whole thing is effortless, low-flame, high-intensity and maximum musicality. Thank you to Kenny Washington for broadcasting this track’s importance for the last 30 years.

Thelonious Monk’s original recording of “Blue Monk”, on Prestige, recorded on September 22, 1954 with Blakey and Percy Heath, is an improvisational masterpiece and a personal favorite, deeply ensconced in my personal pantheon of classic jazz.

At over 7 minutes, it’s a chance to hear these masters develop their ideas over a longer period of time than was usual in the 1950s. Is this free jazz? Not on the surface; it’s a blues in Bb. However, the trio is so in tune with each other, and so supportive of Monk’s conception, that everyone is playing freely; it is, in a sense, free improvisation.

Technically, from a drum perspective, notice these things:

Blakey is playing very soft, fully blended with an acoustic piano and acoustic bass. Blakey was known as a hard driving and powerful player; here’s a great example of him burning at a low volume, a sound he probably used more often than we might assume.

Blakey’s trademark time feel, and his press roll, are now present and integrated into the music. On “Kelo”, a jazz drumming master class, it’s almost the Blakey we know, but here’s the Blakey we definitely know.

Blakey is playing contrapuntally, conversationally, with fully-developed musical ideas during the piano and bass solos. Notice the hi-hat as an independent voice (!) from 1:29 to about 2:05. Then there’s the polyrhythmic left stick on the hi hat starting at about 2:15. (This is truly surreal drumming.) This is followed by an early version of the “Blakey shuffle” from 2:23.

Blakey uses a huge variety of textures, sounds, and combinations as an accompanist. The bell of the cymbals, the two cymbals in combination, hi-hat closed, hi-hat open, etc etc, all are used, with exquisite taste and musicality.

Blakey’s drum solo likewise uses an extensive palette of sounds and textures. including his patented elbow-bending-the pitch-of-the-snare-with-snares-off lick. It’s a wide palette, just like Jim Black. There’s some disagreement about where his solo ends, which these masters take in stride.

“Blue Monk” is a breathtaking masterpiece. Sit back and enjoy.

These five tracks are just the tip of the iceberg of Blakey’s pre-Messengers music. Taken together, they show a master coming into his own, with key elements being introduced, then foregrounded. I’m working on a more thorough, methodical survey of the Wayne Shorter-era Jazz Messengers, five years from November 1959 to Fall 1964.

While I had no direct contact with him (he died when I was 10), Mulgrew Miller and James Williams agreed on one thing about Mr. Blakey— the man was selflessly, almost impractically, committed to maintaining a jazz band, on the road, in recording studios, at festivals, in clubs, wherever they were wanted, until he breathed his last.

Art Blakey believed in the music, the musicians, the audience; believed that jazz was the highest form of musical expression; that jazz was a perfect manifestation of creativity and spirituality. Jazz and a jazz band must be maintained, therefore, whatever the personal cost, until his dying day.

This is exactly what Art Blakey did. In this respect— committed to new music, young musicians, and personal growth until the very end— he reminds me again of Wayne Shorter.

Thank you and all respect, Mr. Wayne Shorter and Mr. Art Blakey.

Goldsher, p. 24, 2002.

Ray Charles, Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, Cannoball Adderley, and others were certainly in the zone of Moanin, and had been for some time. In fact, many things had sounded almost like “Moanin” for a few years, but nothing precisely like it had been done. Miles Davis’ original “Walkin”, which predates “Moanin” by 5 years, features the graceful, supple, and magical Kenny Clarke/Percy Heath hookup, with nothing like a backbeat in the vicinity.

Somewhere in this period Art Blakey traveled to Africa. I’ve found no more info than that; Blakey only spoke about it in general terms (“I had to play my way over on a boat.” “I didn’t study music, I studied philosophy and religion.” etc.). No one seems to know where exactly he visited, how long he stayed, or what he did, but there’s a big hole in his discography from Feb ’48 to October ’48— this seems a plausible length of time for a trip to and from Africa.

Monk’s “Nice Work If You Can Get It”, from the same session, is the first example I’ve found of the “Art Blakey press roll”.

A really beautiful essay on a master of music!

This: "reach a mass audience and advance humanity’s capability..." Yes!

Beautiful essay, thank you!