For Donald Bailey

Part one of two, with testimonials, bio, and a look at Jimmy Smith's early career with Bailey.

In my teens, I loved organist Jimmy Smith, especially his early Blue Note albums with drummer Donald Bailey. At college in 2001, Bill Goodwin solemnly told me that Donald Bailey could create a four-voice polyrhythmic drumset fugue, comparable only to Elvin Jones. Sitting at the bar at Zebulon one night in 2004, Kenny Wollesen told me that Donald’s creativity and wisdom went far beyond the drums.

Ethan Iverson wrote a beautiful tribute to Bailey in 2013, which you can read right here. The first drummer Joey Baron talked to me about was Donald Bailey, Billy Hart told a bunch of us that Steve Gadd in the Seventies reminded him of Donald Bailey in the Sixties, cymbal-maker and drummer Jesse Simpson was a student of Donald’s, and both Bill Stewart and Larry Grenadier sang Donald’s praises in the kitchen at the Vanguard a few weeks ago.

Today, Donald Bailey’s sub-rosa influence is everywhere. Seventy years ago, Donald Bailey was playing expert bebop drums, swinging and creative, with Jimmy Smith. A close listen to Donald Bailey around this time indeed reveals him dabbling in the contrapuntal, polyrhythmic style that Elvin Jones and Tony Williams became known for in the 1960s, just as I’d been told.

Bailey was among the first to play like this, helping to create the rhythmic world we live in today. True, all jazz musicians had an understanding of the basic polyrhythmic rub right at the beginning— drummers Baby Dodds, Zutty Singleton, Paul Barbarin were hearing the music in “2” and in “3” from the beginning, for that’s how American music is made.

Louis Armstrong’s 10 bars of “3” against “2 “in “Hotter Than That” from 1927 notwithstanding, polyrhythms were, at first, more felt than stated, a shared understanding, a secret handshake. By the mid-1950s, they were bubbling up from the underworld to the surface.

Bailey wasn’t alone. Elvin Jones, on his earliest recordings with Miles Davis (Blue Moods, July 1955) and J. J. Johnson (J is For Jazz, July 1956), is just inches away from his mature, six-and-four conception we know and love, while it’s said that another Philadelphia drummer, Edgar Bateman, was making similar moves to Bailey and Jones. Surely there were others— the complete story has yet to be told.

Of course, this stuff didn’t come from nowhere. Art Blakey had been playing triplets and what he called “6/8 in 4/4” since the 1940s, while Shadow Wilson’s chugging, lopsided beat, taking in both “2” and “3”, had been generating incredible heat since he joined Count Basie in 19441. For that matter, Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Max Roach, and all the grand masters of bebop would head underground and play some dark triplets and mystical polyrhythms once in a while.

However, what Donald Bailey, Elvin Jones, and others were exploring was something authentically different, built from the old but genuinely new.

Listening to Bailey for this essay, the phrase “it’s all real” came to haunt me. There’s depth and truth in Donald Bailey, complex layers of meaning that will keep us listening, probably forever. As Larry Grenadier2 said, for Donald, every gig, every recording session, every playing situation was a chance to start from scratch, to create, to experiment, to be involved in the music. His bold four-limb independence and mysterious polyrhythms came from his experiences alone.

We’re hearing Donald Bailey’s very life: his thoughts, experiences, dreams, and hopes. This must be what the cats were trying to tell us when they talked about Donald, about the power and truth of an individual conception; the way a single life can contain a universe.

Donald Bailey was born in March 26, 19333, in Philadelphia, PA, two years and one day after Paul Motian’s birth in the same city, the same year as Rashied Ali, Denis Charles, and Ben Riley.

A Donald Bailey bio hosted at drummerworld.com, while mostly silent on Bailey’s influences and teachers, does mention one name: the Philadelphia pianist William Langford, knowns to us Hassan Ibn Ali— the legendary Hassan. This is telling and helpful. The recently released Hassan solo performances have a spirit similar to Bailey’s: experimental, brave, and profoundly individualistic; music that plays by its own rules; true ancient-to-modern Philly jazz.

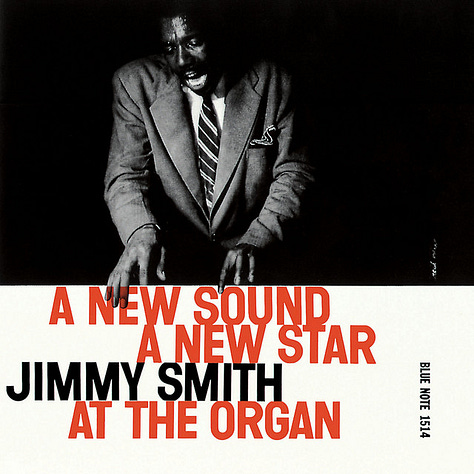

Bailey joined Jimmy Smith, a fellow Philadelphian, around (by his estimation) 1953. Donald’s first entry in the Lord Discography is Jimmy Smith’s second date as a leader, A New Sound, A New Star (Blue Note), a 12” LP recorded in March ‘56 at Rudy Van Gelder’s home studio in Hackensack.

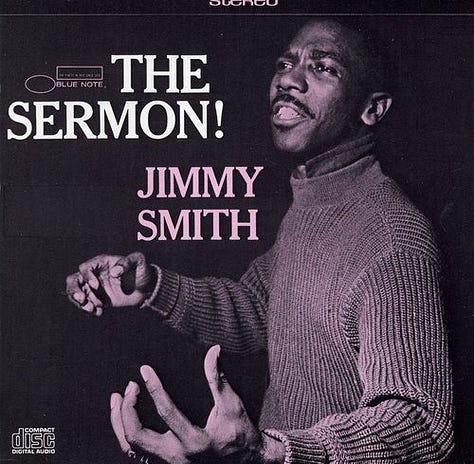

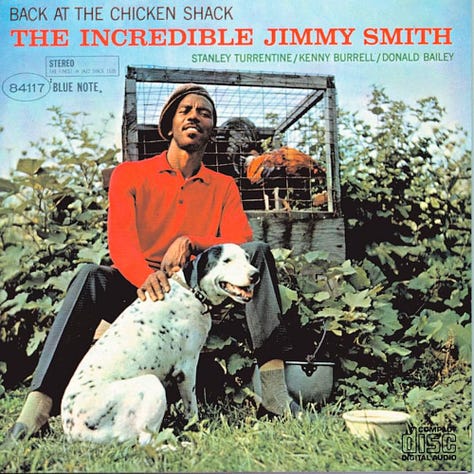

From age 23 in 1956 to age 30 in 1963, Bailey is documented exclusively with Jimmy Smith4 on Blue Note. Beginning with The Sermon5, continuing through classic LPs Crazy! Baby, Home Cookin’, Midnight Special, Back At The Chicken Shack, Rockin’ The Boat, and Prayer Meetin’, Smith found a direction while Bailey developed an approach and vocabulary that had a vast influence, especially on groove-oriented funk/soul/R&B and adjacent sounds, right up to the present day.6

In 1964, Bailey left Jimmy Smith and moved to the West Coast. It’s in this era, 1964 to 1975, that Bailey records some of his best-loved work7 including the legendary quartet of records he made with pianist Hampton Hawes for Contemporary— Here and Now (1965); The Seance (1966); I’m All Smiles, (1966); and High In The Sky (1970).

Around 1975, Donald Bailey moved to Japan, playing in and around Tokyo and recording dozens of albums, most of which are unknown in the States. Bailey’s first date as a leader is from this time and place (So In Love, 1979) and features him not on drums but on chromatic harmonica.

He returned to the States full-time around 1981, living in the Bay Area and freelancing. Donald recorded and toured with Carmen McRae, Jimmy Rowles, and became an important mentor to a younger generation of Bay Area musicians, including Larry Grenadier and Kenny Wollesen. A dedicated teacher, he’s remembered fondly as a dignified presence at the annual Stanford Jazz Workshop.

His second and final date as a leader, Blueprints of Jazz8, was recorded in 2006 and released by the Talking House label. Active and engaged right until the very end, Donald Bailey died in October 2013 at the age of 80.

The history of jazz is not the history of jazz on record. Donald Bailey is much more than the recordings he left behind, yet we gain nothing by ignoring them. To inch closer to feeling Donald Bailey’s contribution, to sense his depth, I have to think about Jimmy Smith, for Bailey recorded more with Smith than with anyone else.

Click this link to see a photo of Smith and Bailey at a Pittsburgh club in the Fifties. Physically on top of each other, they seem to occupy two different worlds, Smith engaging and outgoing, Bailey present but responding to his own reality. As Richard Davis said, a dump can be a paradise: what seems common and everyday can be magical.

Jimmy Smith’s “Back At The Chicken Shack” stands out. Along with “The Sermon”, it’s probably the Jimmy Smith track, an elemental blues over Bailey’s trance-inducing groove. Donald’s odd, fetching, unforgettable, and deeply swinging “Chicken Shack” beat, repeated without variation for 8 minutes, foreshadows so much. The line from Jimmy Smith and Donald Bailey’s “Chicken Shack” to Al Jackson and Booker T. Jones’s work at Stax Records on dozens of soul and funk hits— the bedrock backbeat vocabulary— is easy to hear.

Interestingly, “Back At The Chicken Shack” is a pretty far cry from Jimmy Smith’s early records. A good parallel might be the way James Brown’s “Cold Sweat” was only distantly related to his early hits with the Famous Flames. Like Brown and “Cold Sweat”, “Chicken Shack” is both Smith’s summary and a highly specific brand new thing.

It must have felt like a long journey. In 1956, Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff of Blue Note Records presented their brand-new signee Jimmy Smith as a modern jazz virtuoso to beat all comers, sort of the Blue Note version of Oscar Peterson. Monk was the “genius of modern music”, Bud Powell was “amazing”, but Smith was “The Champ”, (the title of his first hit record), a suit-wearing, sweat-drenched, expert operator of a brand new technological marvel, the Hammond organ. It was hoped Smith’s virtuosity and audience-enchanting charisma might, like Oscar Peterson, reach beyond hardcore jazz fans.

So Smith and Alfred Lion got to work. They started with burners (“The Way You Look Tonight”, “Sweet Georgia Brown”), Errol Garner-like bounces (“You Get ‘Cha”, “The High and The Mighty”), plenty of ballads (“Deep Purple”, “Moonlight In Vermont”), and some blues (“The Champ”, “Bubbis”). But what we think of today as Smith’s calling card— the long beguiling blues with shades of gospel and soul— was not part of the original package. Initially, there were no trance-inducing shuffles: no sermons, no home cookin’, no midnight specials taking you back to the chicken shack.

It seems obvious now for Smith to reach into the blues tradition and iconography, but it couldn’t have seemed so at the time. Oscar Peterson was on Norman Granz’s Verve label, presenting ‘mainstream’ jazz as sophisticated sounds for grown-ups— perfect for Peterson. But Smith was on Blue Note, the home of the new, which is what Smith aspired to be.

Here’s Smith’s story— he called it “his classic”— of the night that his idols gave him their blessing:

“They [Sonny Rollins, Hank Mobley, Art Blakey, Max Roach, and Thelonious Monk] thought I was overdubbing on the record [“The Champ”, from March 1956] because I was playing so fast, so they came to see for themselves.

Well, after a while they all started coming up to play. All those horns and Art asking to take Donald Bailey’s place. The house was burning. Then Monk walks up to the bandstand, gets behind me and starts playing with me on the organ.

Man, that was the most exciting thing that ever happened to me besides being born9.”

Smith’s ambition was to be successful and to be one of the cats. He had been accepted, so now it was time to get over. How to do it? Horace Silver and Art Blakey gave us “The Preacher”, so Smith gave us “The Sermon”. Two years later, we’re “Back At The Chicken Shack”, a canny and classy distillation of modern jazz (viz. Bailey’s beat) into something for a wide audience.

This story is best told in sound:

“J.O.S.”, from The Sermon, recorded August 25, 1957. Here, a year into Smith’s long career, his tone has evolved from the piercing chirp of A New Sound, A New Star and the live dates in Wilmington, DE and Harlem into the mellow, round, vocal-like whistle we all know. “J.O.S.” is the sort of thing Smith was up to early on: minor key, up-tempo, with long, exciting solos from George Coleman (on alto!), fellow Philadelphian Lee Morgan, guitarist Kenny Burrell, and Smith. It’s classic Blue Note modern jazz.

But dig Donald Bailey. On “J.O.S.”, Bailey keeps Smith, who’s loosey-goosey and always on the brink of pulling ahead, roughly aligned. He does so not by insisting on the tempo with a clean, loud cymbal beat, but with a clattering dialogue between his bass and snare— Bailey’s bass drum is just about barking at Smith. This isn’t the smooth flow of Kenny Clarke and Billy Higgins, where an embroidered tapestry of eighth notes emerges from a glittering ride cymbal. Rather, it’s oblique, almost contrary to the solos. That stuff Bailey’s playing is really hard to do— you can maybe play it in a practice room, but to get it flowing in the moment with a band is really something. Donald Bailey was a virtuoso.

And he gives the track layers of feeling and meaning— while Smith is working up a sweat for the crowd, Donald Bailey is exploring his bass and snare, fully engaged and supportive, but on his own path. With Smith, Bailey keeps me listening, because nothing is what I think it is.

“When Johnny Comes Marching Home” from Crazy! Baby, recorded January 4, 1960. Swinging out on a well-loved folk tune with strong Civil Rights-era implications is a step from “The Champ” towards Smith’s embrace of the new/old popular/jazz hybrid on “Back At The Chicken Shack”. There’s an emotional gulf between Smith and Bailey. Contrast creates interest; Smith and Bailey are contrasting but complementary feelings. With his almost-straight eighth ride cymbal and ever-changing combinations of rim, snare, and tom, Donald keeps the energy up, remaining cooly down-to-earth while Smith tries for further.

“Back At The Chicken Shack”, recorded April 25, 1960. This is something else, different from anything Smith had done. The ancient blues now had a new ultra-sharp suit of clothes, dressed to kill and ready to conquer the world. Smith, Bailey, Kenny Burrell, and tenor saxophonist Stanley Turrentine gave us something special.

We’ve heard Bailey’s four-limb independence, hints of polyrhythms; we get how he understands, supports, and relates to Jimmy Smith. Now he uses all that to craft and play an unforgettable beat: a shuffle with the hi-hat on the “ands” and, in place of a backbeat, the left hand on “2 and 3”, which Ethan Iverson hears as “yeah (snare) uh-huh (tomtom)!”

Donald has distilled his drum life of independence and polyrhythms into a sophisticated pop music hook, an integral part of the tune, singing his one-bar song, with no variations or fills, for a trance-inducing 8 minutes, then deploys his understanding of Jimmy Smith to vibe out and play it. Today, this would be created electronically. But Bailey just did it, and he did it for us. How lucky we are. All gratitude and respect.

“When I Get Too Old To Dream” from Back At The Chicken Shack, recorded April 25, 1960. On “Chicken Shack”, Bailey played the same thing in every bar, and on the very next tune, he plays something different in every bar. Great as Smith and Turrentine sound, Bailey is the star here. His loping, chugging cymbal beat, with a strong underlying triplet pulse, is the framework: the cymbal beat says “three”, but Bailey’s snare arrives at “four”, (sixteenth notes with Stanley). For Turrentine’s final chorus, Donald plays quarter notes on the hi-hat! Here it is— polyrhythms (triplets and sixteenths, three and four), coordination (sixteenths on the snare, quarters on the hi-hat), and something mysterious and honest tying it together. Donald Bailey on this track is a dream hiding in the everyday.

“When My Dreamboat Comes Home”, from Rockin’ The Boat, February 7 1963. An oldie in 1963, going back to Bing Crosby in the Thirties, my dreamboat on this track is, once again, Bailey’s hi-hat. Donald’s elaborate variations on a boogaloo, with shades of New Orleans parade beats, is built around his chattering left foot, but spread across his whole four-piece drumset. Here, Bailey really anticipates the percolating sixteenth notes of the Bay Area drummers— Greg Errico, David Garibaldi, Mike Clarke, Gaylord Birch, others. As Billy Hart said, Steve Gadd in the Seventies reminded him of Donald Bailey in the Sixties.

“Prayer Meetin” from Prayer Meetin, February 8, 1963. With the hi hat on the “ands”, just like “Chicken Shack”, here’s Bailey’s unadorned backbeat on the snare. Donald is playing exactly the way a great studio drummer might play on a Seventies pop record, a memorable and creative beat played with total conviction and no variation. Even the loud snare drum points to the future. But everyone’s playing like this— Kenny Burrell, Stanley Turrentine, and Jimmy Smith could have played hip bebop, but that’s not the idea. Burrell plays his one-bar riff over the three chords, while Smith and Turrentine’s solos are a mix of blues and bebop. This is pure jazz with a pop music sensibility and I just love it.

By 1963, I bet Donald Bailey was feeling the need to spread his wings and prove himself in some other contexts. He left Jimmy Smith, who replaced him with Billy Hart, and was on the West Coast by 1964. For the next decade or so, Bailey was a fixture of the L.A. scene, and left behind some memorable records.

For Part 2, I’ll examine that era of Donald’s music with a special focus on his work with pianist Hampton Hawes.

Until then, I’ll be thinking about Jimmy Smith and Donald Bailey, a sound we’ve known for decades, but with a story and layers of emotion that I’d never contemplated.

Special thank you to Larry Grenadier for our conversation about Donald Bailey.

Both Art Blakey and Shadow Wilson were, of course, essential drummers to Thelonious Monk. Monk’s contribution is simply so large that it’s hard to perceive.

Grenadier played extensively with Bailey as a teenager in the Bay Area.

Bailey’s AllMusic bio by Scott Yanow gives his birthday as March 26 1934, but in a 2011 video interview Bailey gave to NYC organist Jon Hammond, he says he was born in 1933. I’m going with Bailey.

Bailey’s first recording session outside the Smith orbit is George Braith’s Two Souls In One (Blue Note, September 1963), which might coincide with Bailey leaving Smith.

Bailey is not on the legendary title track— that’s Art Blakey. Bailey is on “J.O.S.” (James Oscar Smith, Smith’s full name), originally issued on The Sermon, and a standout in its own right.

Certainly, there are few NEA Jazz Masters whose work has been thought about less than Jimmy Smith. Indeed, as excellent as some of Smith’s work without Bailey is (a live date in Europe with Billy Hart from 1966, the collaborations with Wes Montgomery and Grady Tate, Root Down with Paul Humphrey from 1972, and parts of Damn!, with Art Taylor, from 1994), some creative juice is missing from Smith’s later music. Bailey certainly brought something special to Jimmy Smith. Absent Bailey, Smith rarely transcends, giving rise to the use of words like “predictable” and “uninspired” to talk about his music. In this way, Bailey’s contribution is highlighted— listen to how magical Jimmy Smith could be with Donald, and note how seldom he was without him.

Save, of course, the Trane bootleg from 1963 in Montreal, which you can hear right here. Thank you Ethan Iverson!

The album’s proper title is Blueprints of Jazz Vol. 3. Not sure why it’s called “Vol. 3”.

Quoted by Dan Oulette, from an interview with Smith in 1994. From Oulette’s book The Landfill Chronicles (Cymbal Press, 2024), found on wbgo.org

Kenny Burrell toured Japan in 1976 with an excellent pickup band comprised of Tsuyoshi Yamamoto on piano, Isao Suzuki on contrabass, and Donald Bailey, who was a resident of Japan at the time. I saw them in Hiroshima with a girl I liked. Kenny had just released "Sky Street," and the quartet opened the show with the album's centerpiece, a Jerome Richardson composition titled '3000 Miles From Home." Bailey played this lovely, loping backbeat tune with bells attached to his sticks, and his performance was riveting. The girl quietly took my hand before the end of the song. That was 49 years ago, but I remember it like yesterday.

I very much appreciate “a dream hiding in the everyday.” And so much else about this thoughtful appraisal. You may be aware, but another young musician who benefited directly from Bailey’s time in the Bay Area was Vijay Iyer.