For Horacee Arnold

Listening to the great jazz drummer with Alvin Ailey, Chick Corea, Billy Harper, and others.

At William Paterson University, where I studied in the late Nineties and early 2000s, I was learning the most from my fellow students, great players like Freddie Hendrix, Jared Gold, Sam Barsh, Ryan Blotnick, Sam Sadigursky, and especially drummers Jamieo Brown, Johnathan Blake, Josh Dion, Mark Guiliana, Jim Oblon, and Tyshawn Sorey. Surrounded by these and other huge talents, I was never at a loss for something to practice.

As an incoming freshman, I wanted to study with the great drummer John Riley. But I went where I was told, and for my first year, I was placed not with Mr. Riley but with the other drum teacher in the jazz program, a gentleman named Horacee Arnold.

Horace Emanuel Arnold was born in Wayland, Kentucky in 1937. After a stint with the Coast Guard and time in Detroit, Arnold was in Louisville, KY by 1959, playing with composer/cellist/educator David Baker and in a trio with pianist Kirk Lightsey and bassist Cecil McBee1.

Max Roach, the guiding light of 20th century drumming, was responsible for introducing Arnold to the wider music world. When Max heard Horacee2 in Indianapolis, in 1960, Roach invited Arnold to spend the next summer with him in NYC.

By 1964, Horacee was a working drummer in New York, playing with Bud Powell for a week at Birdland, and gigging with Charles Mingus and Hassan Ibn Ali, among others. Billy Hart remembers Al Foster taking him to Birdland to hear Horacee in this period; according to Billy, at the time Horacee sounded exactly like Roach.

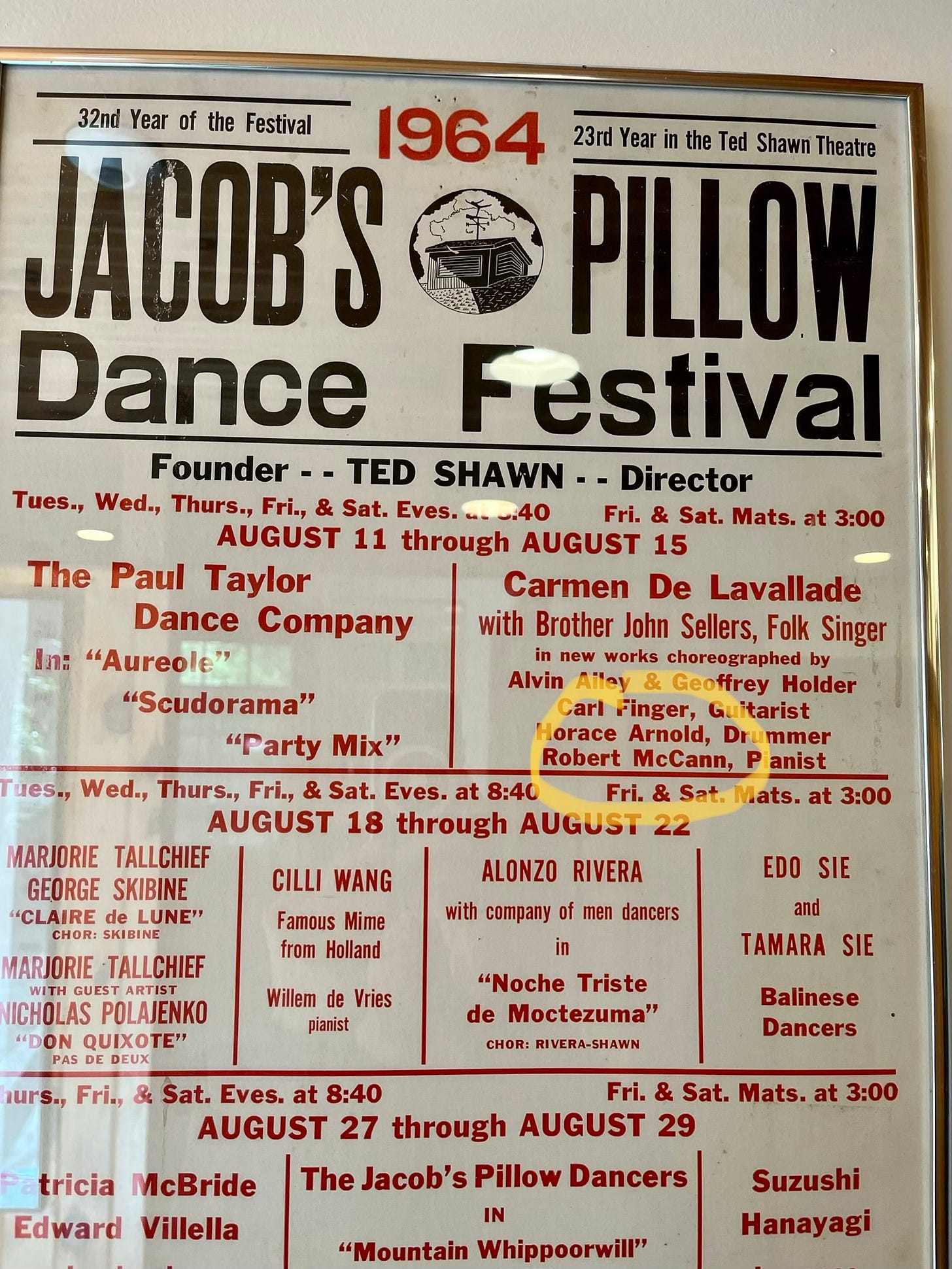

Arnold continued, touring with Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masakela3 , and through Max Roach, he began a long association with choreographer Alvin Ailey. His time with Ailey shaped Arnold’s sense of what was possible in music. As he told journalist Lee Jeske in 1984:

“Alvin was the one person who taught me about presentation, staging, and just general impact. That was the most important musical experience, as well as theatrical experience, I’ve ever had…..After having worked with Alvin, I felt that there was no musical experience that I couldn’t get something from and apply in an artistic way.”4

I think this is a key to understanding Arnold’s individuality. In addition to mentoring with jazz masters, Horacee was collaborating and touring with one of the world’s greatest choreographers, incorporating aspects of Alvin Ailey’s vision into his own. I keep this in mind as I listen to Arnold: there are dancers behind him.

In 1967, Horacee appears on saxophonist Robin Kenyatta’s debut leader date, Until (Vortex5) The track “This Year” is on YouTube as a vinyl rip, and allows us a glimpse of Arnold as he’s coming into his own. Kenyatta deserves much attention— he’s a dynamic player with his own take on common practice jazz of 1967, but for now we’ll focus on Horacee.

On this track— the earliest Horacee Arnold recording I could find— Arnold’s following the music wherever it leads, drifting in and out of meter, with a complete command of the Elvin Jones-Tony Williams vocabulary. Horacee is involved, making choices, catching the transitions, and bashing.6 This is a new drummer on the scene.

Now 30 years old, Arnold was also ambitious. Around this time, he formed the Here And Now Ensemble, with Kenyatta, Sam Rivers, Karl Berger, Reggie Workman, and others. This was a grant-funded (Young Audiences) band— shades of 2023— and their mission was to bring the new music to the community by playing in schools and community centers instead of nightclubs and jazz festivals.

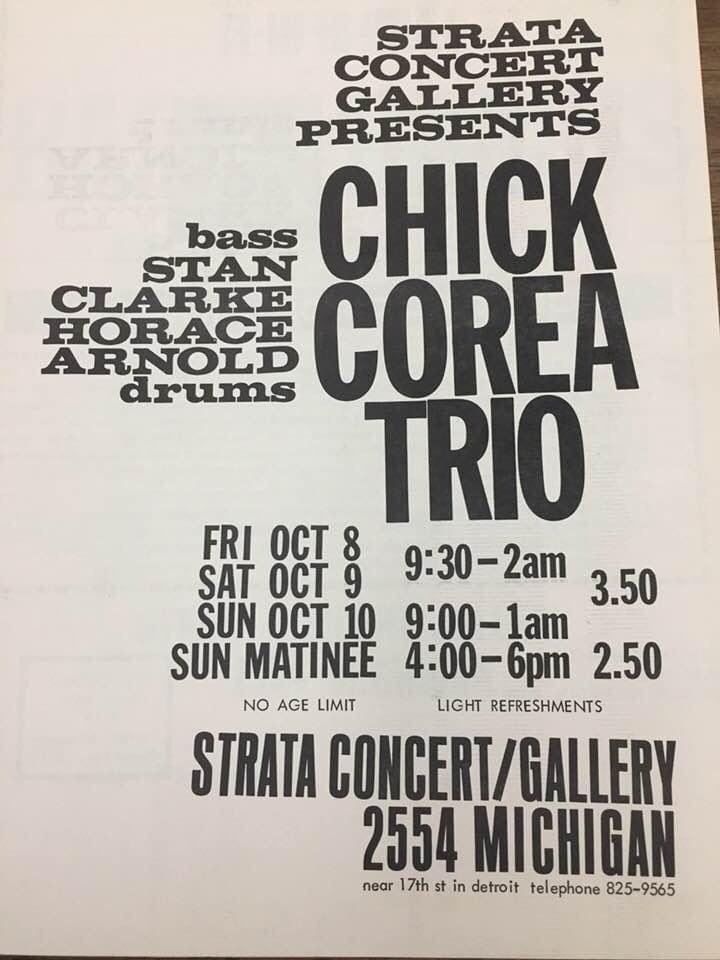

Whatever Horace was involved in, it was leading him to some special places, because his next major outing was with Chick Corea.

Recorded in May 1969, Chick Corea’s Is (Solid State, 1969) and Sundance (Groove Merchant, 1972)7 sound fresh and exciting 54 years later. Here, Horacee is paired with Jack DeJohnette8; together, DeJohnette and Arnold create a dense forest floor of rhythm and energy on the following tracks, all composed by Corea:

“Jamala” (composed by Dave Holland, both takes)

“Converge” (both takes)

Is and Sundance are exciting, fun, wild albums. It’s startling to hear the young visionaries— Woody Shaw, Hubert Laws, Bennie Maupin, Chick Corea, and Dave Holland, in addition to Arnold and DeJohnette— create the music of the future. This isn’t fusion per se, but Age of Aquarius rock and R&B are present, the sound of the era.

In 1969, DeJohnette and Horacee sound very similar; I’m only occasionally totally certain who’s playing what. The best clue is that DeJohnette is completely unmistakable: if Jack is playing, you don’t wonder who it is.

Though their vocabulary and approach were similar, Arnold favored a more ‘classic’ drum sound than Jack. Horacee’s perfectly-tuned Gretsch drums, played with a nuanced but slightly heavier touch, gave him a thick, deep sound on the snare and toms. So, with those observations, I’ve found some standout moments for Horacee Arnold on these records:

The charismatic Tony Williams-on-“Nefertiti”-style fills from 3:29 to 3:55 on the swinging, earwormish “Sundance”— that’s Horacee; on “Song Of The Wind”, I hear DeJohnette on brushes while Horacee is on sticks, swinging in perfect simpatico with the band. Finally, the sprawling 30-minute track “Is” features a percussion ensemble at the top and Horacee dialoguing with Woody Shaw from about 3:55 to about 9:16.

This section of “Is” is a highlight— Arnold and Woody Shaw find a coherent middle ground, where aspects of the bebop ideal merge fully with the possibilities of 1969.

Arnold’s voice and concept were a perfect complement to Corea. Finding a way to fuse the ‘new thing’ of Sunny Murray, Milford Graves, and Rashied Ali with the hip, ultra-modern Tony Williams and Elvin Jones world, wrapped up in his expansive, theatrical sensibility, Horacee arrived at sound that was related to Jack DeJohnette, Joe Chambers, and others, but was all his own.

After Corea’s Is and Sundance, Arnold disappears, at least from the Lord Discography. As Horacee generously shared with me years ago, he had many comings and goings in jazz— periods when he would not play, or at least not take gigs, times when he would set aside the drums for composition or classical guitar.

However, I remind myself: the story of jazz is not the history of jazz on record. Even if Arnold wasn’t gigging, touring, or recording, he was evidently working, for in the early Seventies, he struck up a friendship with none other than John Hammond, the grand old man of the 20th century record industry. When Hammond inquired about Horacee’s music, Arnold had tapes of a gig in Montreal for Hammond to hear. Hammond was evidently impressed— it was Hammond who arranged a Columbia Records contract for Arnold, and it’s Hammond who produces Horacee’s debut leader date.

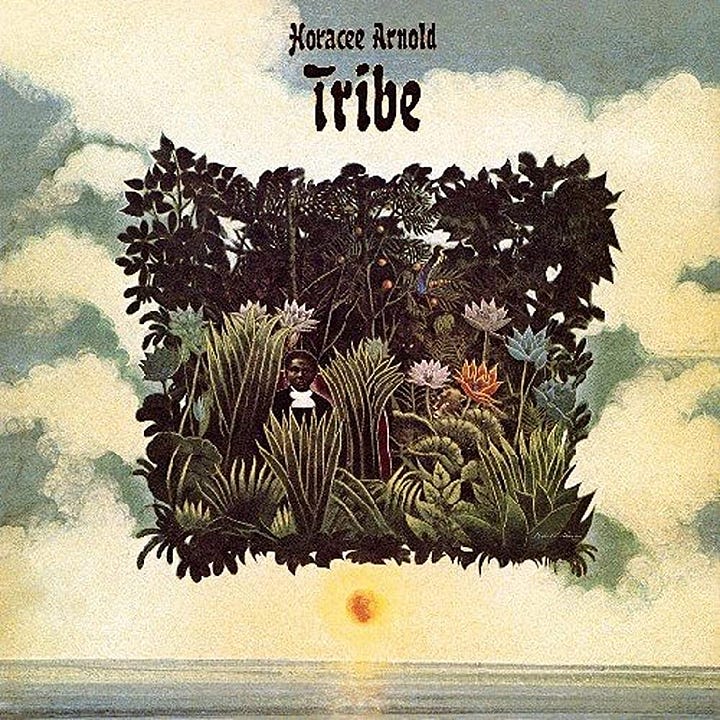

Tribe (Columbia, 1973), Horacee Arnold’s debut as bandleader and composer, suggests the excitement and scope of fusion, but with an acoustic foundation. Built around woodwinds, mallet percussion, acoustic guitar and bass, and percussion, Arnold’s take on the music in 1973 opened up some vistas in my mind; Tribe gets into you at unexpected moments: there is something deeply theatrical about this music. The closest analogue I can think of is Bennie Maupin’s The Jewel In The Lotus (ECM, 1974), a similarly beguiling, hard-to-classify mid-Seventies jazz masterpiece.

All but two of the tracks are by Arnold, and show a promising, developing compositional voice; the overall sound of Tribe, with the marimba and the flute, is unique, engaging and listenable; and of course, everyone sounds great. As the record plays, I have to remind myself, “This is Horacee’s first album as a leader!”

The album opener, “Tribe”, after some guitar and drum flourishes that catch my ear every time, becomes an attractive straight-eighth 6/4 vamp; the band and dancers enter, Joe Farrell solos, and they dance around the groove. Arnold hangs back, blends in, creating interest with tiny variations and changing details. “Banyan Dance” is a strong, memorable melody which gives way to a light-textured modal burner, with solos by saxophonist Joe Farrell, vibraphonist Dave Friedman, and a great drum solo. Much of the album could be set to dance or theater; there’s something deeply expansive about Arnold’s conception.

Arnold had his own take on post-Coltrane, fusion-adjacent jazz, gently nudging it towards a wider world of modern dance and theater. The references are familiar, but Horacee does his own thing with them. Tribe shows that Arnold was a leading light in 1973; it’s a special record, an impressive debut as a leader.

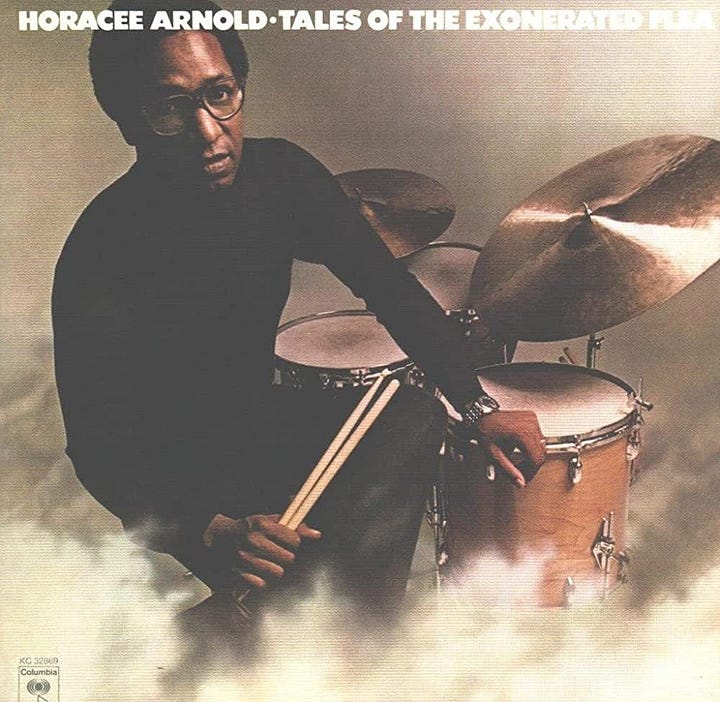

Tales Of The Exonerated Flea (Columbia, 1974), Arnold’s second (and so far, final) leader date, seems to have a wider reputation than Tribe. Certainly, the outlandish title is unforgettable. Overall, the music has more brawn and heft, more akin to Mahavishnu Orchestra and Return To Forever, than Tribe. This is due to in part to Arnold’s writing— the first three tracks are essentially a sequence of interlocking or interconnecting vamps, with solos— and to the presence of electric bassist Rick Laird and keyboardist Jan Hammer, both members of the original Mahavishnu Orchestra9.

On the opener “Puppett Of The Seasons” , a relentless 10/8 groove is the basis for some hot dialogue between guitarist John Abercrombie and Sonny Fortune on soprano sax, suggesting a middle path between Lee Morgan and Billy Harper and Mahavishnu. “Delicate Evasions”, in a trance-like 6/4 with Arnold on percussion instead of drumset, meanders charismatically, a nearly platonic percussion-centric jam. “Euroaquilo Silence” is an open-tempo dialogue between Hammer and Arnold; Arnold’s beautiful sound and command of the language is front and center. Available on all streaming sites as a bonus track, “Timios” continues in the vein of Tribe, featuring some delightful 4/4 swing with solos from Fortune on alto flute and Hammer on piano; the music opens up and breathes, and Arnold’s mastery is on full display.

After Flea, Horacee kept busy, touring with Archie Shepp, Kenny Burrell, and Billy Harper. With Harper, Arnold made three great albums in the late Seventies, all currently streaming on Apple Music:

Soran Bushi, B.H. (Denon, 1978)

Billy Harper In Europe (Soul Note, 1979)

The Awakening (Marge, 1979)

Soran Bushi, B.H. pairs Horacee with the incomparable drummer Mr. Billy Hart10. That’s Arnold on the left channel, and Billy on the right. On the up-tempo “Trying To Get Ready”, Horacee and Billy manage to be busy, dense, transparent, and tasteful all at once. When Harper solos accompanied only by the drummers, I’m floored by how simpatico Hart and Arnold are— loose and tight, united and divergent. I can’t imagine playing 10 minutes of this tempo with another drummer, and having it be so seamless. Based on this track, Arnold and Hart shared an intense bond11.

Recorded while the group was on tour in January 1979, Billy Harper in Europe is good, and includes a great rendition of Harper’s classic tune “Priestess”, often heard these days at gigs by The Cookers, but I gravitate more towards The Awakening, recorded just a few days later. Both albums should be heard: they provide a glimpse of a red-hot Harper Quintet, and feature great Horacee Arnold performances.

In the years since Tribe and Flea, Arnold’s sound seems to have gotten deeper and bigger. He’s now using heavy cymbals and larger drums, but he’s noticeably more focussed on swinging, less on filling, rolling, bashing. He leaves lots of space for the virtuoso soloists (Harper, trumpeter Everett Hollins, and pianist Fred Hersch— yes, the Fred Hersch), and is both firing up the band and holding it down at the same time. This is masterful jazz drumming.

Check out the Arnold/Harper duet after Fred Hersch’s solo on “Soran Bushi, B.H.” on The Awakening for a summary of everything special about Arnold: he keeps the temperature and energy level sky-high, yet is playing simply, transparently, openly, creating contrast to Harper’s boiling-over intensity.

Tales Of The Exonerated Flea was widely praised in 1974, earning a five-star review in DownBeat, and still has a reputation. Yet the follow-up to Flea hasn’t appeared12. Clearly, Arnold has more to offer; for now, his music should be heard.

Horacee Arnold is with us today; I hope he’s playing somewhere right now. (Around NYC, Arnold is, at best, infrequently heard.) Thankfully, he remains an effective educator at William Paterson University and at the New School.

This is a profoundly gifted musician, certainly one of the leading players of the Sixties and Seventies. Horacee’s expansive mind connected cutting-edge 60’s jazz to parallel developments in theater and dance; this is still fertile ground for development, and is much on my mind as I continue working with the Mark Morris Dance Group.

Much of Arnold’s contribution, the basis for the high esteem in which he’s held— Freddie Waits describes hearing him everywhere13, and loving his playing for years; Billy Hart cheered when I mentioned his name in a phone call; Will Calhoun thanks him in the liner notes to the first Living Colour album— is invisible, or really, inaudible. Basically, Horacee is an important player on a scene that has largely vanished; that’s a hard truth for me to accept14.

As I listen to Horacee, read the interviews, and think of the conversations, a clear picture almost emerges; a great, multi-faceted player, who came up through the ranks of the masters, unafraid to buck all convention and make his own music; a community-minded player who performed in schools and became a dedicated teacher; an ambitious musician, writing and forming bands, making records as and when he could. A living master, one who might have a moment of recognition yet.

Click the links, hear some sounds; share your experiences with Horacee in the comments…thank you all!

All gratitude and profound respect for Horacee Arnold.

Both Lightsey and McBee were serving in the military, stationed at nearby Fort Knox, KY.

The extra ‘e’ on Horacee’s first name is a stage name, apparently adopted to fill a requirement for a stage name for the musician’s union in Louisville. The letter ‘e’ was chosen from Arnold’s middle name, Emmanuel. He seems to have first used it in his recording career on Tribe (1973). However, for the sake of consistency, I’ll refer to him as ‘Horacee’ throughout the piece. I’ve also heard people that know him refer to him as both ‘Horace’ and ‘Horace-EE’, which of course, is his name: Horace E. Arnold.

According to Arnold, that’s him on Masakela’s Grrr (Mercury, 1966).

Lee Jeske, “Horacee Arnold: Examining The Values”, Modern Drummer, November, 1984.

This is the same Vortex, an Atlantic Records subsidiary, that issued the first two Keith Jarrett albums.

Arnold certainly suggests Tony Williams in his playing with Robin Kenyatta. However, in the Colloquium III MD (February/March 1980) interview, the drummers mentioned as influences by Freddie Waits, Horacee, and Billy Hart are: Edgar Bateman, Donald Bailey, Wilbur Campbell, Joe Charles (I don’t know this name), Curtis Prince (nor this one), a drummer named Mousey (apparently a Baltimore drummer; again, no idea who this is), James Black, Smokey Johnson, Burt Myrick (not known to me), and Jimmy Lovelace. That list of names shows just how expansive and broad-minded Arnold, Hart, and Waits were. I have a lot of listening to do. For all I know, Arnold and Tony Williams are both imitating Burt Myrick, Mousey, or Curtis Prince. However, Williams’ effect on the scene was galvanic: even Herbie Hancock played Tony Williams licks. So, while we can assume some general influence, I don’t think we can go beyond that.

All tracks from both releases are available via streaming as Chick Corea: The Complete “Is” Sessions (Blue Note, 2002). Produced by Michael Cuscuna, this is all the material released on Is and Sundance, with alternate takes and excellent sound.

The pairing of DeJohnette and Arnold recalls the pairing of DeJohnette and Lenny White a few weeks later on Bitches Brew, and in general is part of the expanding percussion section of late Sixties/early Seventies jazz and pop music. This impulse was given its fullest expression when Max Roach formed M’Boom. More on this as the situation develops.

In the liner notes to Exonerated Flea is the statement “Drums provided by: Gretsch Drum Co. and Billy Cobham”; I guess Cobham lent Arnold a kit for the sessions? Definitely, the resonant, classic jazz sound we’ve heard from Arnold is mostly absent here. This note also means that three of the five members of the original Mahavishnu Orchestra are mentioned in the credits to Exonerated Flea.

Hart would soon join Arnold and Mr. Freddie Waits in Colloquium III, an un-recorded jazz percussion ensemble, intended as a parallel to M’Boom. (See footnotes 5 and 12.) This album is, so far, as close as I can find to a glimpse at what Colloquium III might have sounded like.

The drum duet with saxophone solo is also on the title cut; that is “Soran-Bushi, B.H.” on the album Soran-Bushi, B.H. This is an even more freewheeling performance from Horacee and Billy than the duet on “Trying To Get Ready”.

In 2014, Arnold was releasing YouTube videos, building up anticipation for the release of a new album, titled All Times Are In It. As far as I can tell, only one track has been released. Horacee’s website lists 12 tracks, and allows us to hear clips. (His website also features some nice pics of Colloquium III.)

“Colloquium III” by Cheech Iero, Modern Drummer, February/March 1980.

All respect for trumpeter David Weiss and The Cookers (Billy Hart, George Cables, Cecil McBee, Billy Harper, Eddie Henderson, and others) for keeping this sound alive today.

Many thanks for an excellent piece on one of the lesser-known greats. I had the pleasure of working with Horacee on Billy Harper's 1993 recording "Somalia." During the planning stages I had suggested to Billy that we augment his quintet with a second bassist (inspired by Lee Morgan's final studio session), but Billy decided to add a second drummer instead. The combination of then-regular drummer Newman Taylor Baker and Horacee produced fireworks, particularly during the freer passages of the epic 'Thy Will Be Done.' I remember how Billy had the drummers tune their kick drums to sound alike so they would sound like one monster drummer.

one more comment... apparently bill stewart studied with horacee as well...