By 1964, ideas in jazz once considered fringe or avant-garde were entering the mainstream. One group of musicians seemed intent on blending straight-ahead and avant-garde conceptions; among them, Richard Davis, Eric Dolphy, Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, Andrew Hill, Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Hutcherson, Jackie McLean, Grachan Moncur, Sam Rivers, Woody Shaw, Tony Williams, Larry Young, and drummer/composer Joe Chambers.

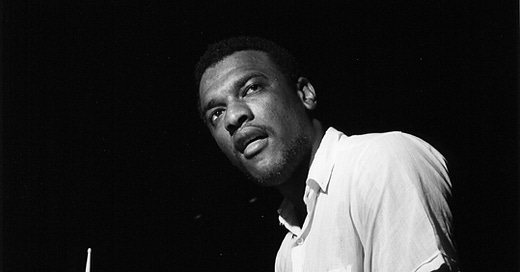

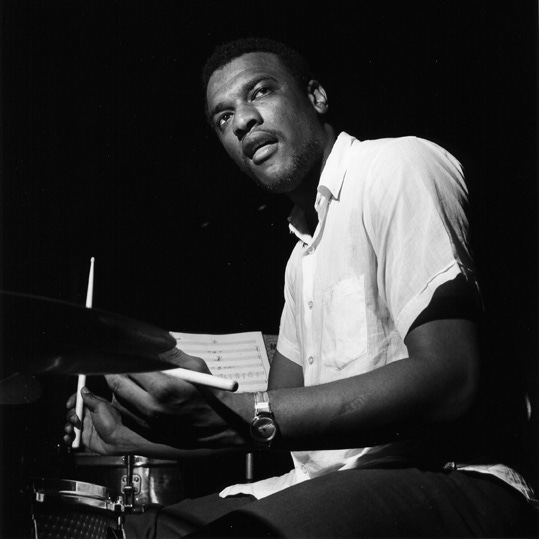

Joe Chambers is of course one of our greatest living masters, an active, vital musician today and a direct link to the 60’s. A master drummer and important composer, Chambers’ compositional sensibility seems to inform every musical choice he makes.

The classic 60’s Blue Note records featuring Chambers and Co. all suggest a liminal or blended space, where the bebop tradition, free improvisation, contemporary classical music, and current popular sounds all twist around each other and float through the room. This is now part of jazz’s mainstream, and Joe Chambers is one of the authors of this aesthetic.

Simply put, as a jazz drummer with the mind of a composer, Joe Chambers was ahead of his time.

Chambers was born in 1942, outside Philadelphia. Music seems to have entered his life through school and church, and by high school he was playing drums and studying composition. In the early 60’s he toured with Lou Donaldson, and makes an auspicious recording debut on Freddie Hubbard’s Breaking Point (Blue Note, 1964).

On Breaking Point, Chambers conducts Hubbard’s quintet through one of the most varied and balanced programs on a jazz record from any era, covering everything from open time to a gospel waltz, straight-ahead 4/4, calypso, and a Coltrane-esque modal churn. It's astonishing how confident Chambers is with this variety, how much command of the language he has, how developed his voice and sensibility is.

Tellingly, Breaking Point concludes with a Joe Chambers original, “Mirrors”, an asymmetrical A-B-A fantasy, with a melody somewhere between a jazz ballad and contemporary classical music. "Mirrors" in specific and Breaking Point in general effectively announce the Chambers Paradigm1.

What followed was 5 years of intense recording activity for Chambers and Co.; these records document a scene, showcase Chambers’ conception of the jazz drummer as composer and collaborator, and demonstrate Chambers’ unsurpassed musicianship.

Consider….every record featured new music, new ideas, new possibilities, sometimes new, unheard players or unusual combinations of players; each date required incredible amounts of time to put together— composing, practicing, rehearsing, recording; this was a sound these musicians were creating without an obvious precedent; this was an evolving sensibility— the music changes as time goes on; finally, no current jazz is unaware of this sound…..

This is just the highlight reel, all Blue Note albums unless otherwise noted:

Andrew Hill: Andrew!

Andrew Hill: Pax

Bobby Hutcherson: Dialogue

Sam Rivers: Contours

Bobby Hutcherson: Components

Wayne Shorter: Et Cetera

Andrew Hill: Compulsion

Wayne Shorter: The All Seeing Eye

Joe Henderson: Mode For Joe

Bobby Hutcherson: Happenings

Wayne Shorter: Adam’s Apple

Chick Corea: Tones For Joan’s Bones (Atlantic)

Wayne Shorter: Schizophrenia

Bobby Hutcherson: Oblique

McCoy Tyner: Tender Moments

Tyrone Washington: Natural Essence

Bobby Hutcherson: Patterns

Charles Tolliver: Paper Man (Strata-East, Arista, Black Lion)

Bobby Hutcherson: Total Eclipse

Bobby Hutcherson: Spiral

Bobby Hutcherson: Medina

Stanley Cowell: Brilliant Circles (Polydor)

Bobby Hutcherson: Now!

Staring at this list2, with the sound of these records rattling around in my head, Chambers’ contribution and excellence seems almost to have physical weight. As a member of a cohort, Joe Chambers, in the midst of a tumultuous decade, carved out a blended space where modern composition sits at ease within jazz and improvisation, and vice versa3. And, he did it with style, as a complete individual.

His individuality starts on the drums.

A big dry ride cymbal sits at the center of Chambers’ music; a clear sound, played precisely, perfect for the rarefied soundscape he occupies. Chambers uses some polyrhythmic ideas associated with Elvin Jones and Tony Williams (implied metric modulations, triplet subdivisions, etc), and occasionally plays some fancy hi-hat/snare/bass combinations, which give the music just a touch of slickness.

Much of the time, though, Chambers is dry, cool, and focussed, which gives incredible weight and meaning to the moments when he opens up, gets louder and more active. In this balance, I detect a composerly instinct.

This is attached to Chambers’ commitment to the composition. For example, when he’s with Freddie Hubbard, playing “D Minor Mint”, a swinging 32-bar tune in 4/4, he plays with as much attention to detail as his own abstract composition “Dialogue” with Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, Richard Davis, et al4. For all of his intensity and fire, Joe Chambers epitomizes sensitivity, to the composition, the band, the intent of the piece, etc.

Mr. Chambers is, happily, still with us, touring some and releasing fine new albums on Blue Note (Samba de Maracatu, 2021, and Dance Kobina, 2023). For now, I’ll focus on an important record from the 60’s, and a solo album from 1978. Finally, I’ll offer a few personal favorites, with links and comments.

Vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson’s Dialogue is a collective experience; the compositions by are by Andrew Hill and Chambers, and soloists Freddie Hubbard, Sam Rivers, Hill, and Richard Davis are all featured. Hutcherson and Chambers collaborated throughout the 60s; Dialogue is a perfect snapshot of Chambers’ mastery of the blended space.

“Catta” is a minor-key Latin vamp and melody by Hill; simple on the surface, totally mysterious in execution. Joe plays it cool and lets the vamp swirl, grow, and change underneath sublime solos and Davis’ apposite grooving. Chambers’ own “Idle While”, a 44-bar, through-composed waltz, is lyrical and unpredictable; Hill lays out while Joe and Richard play the form. Hill’s “Les Noirs Marchant” (“The Marching Blacks”) is political and almost programmatic. Chambers, like a great conductor, keeps the group improv moving and connected to the initial theme; he makes the piece a composition.

“Dialogue” is the most abstract piece on the album, but isn’t really a free improvisation; rather, the group collectively elaborates on Chambers’ composition— shades of AACM and parallel avant-garde movements. Finally, Hill’s “Ghetto Lights” is slightly more conventional fare, and Joe’s light backbeat feels fresh and vital. A Blue Note blues-like tune is momentarily strange, and we can hear it connect to the abstraction of the previous tracks.

Dialogue is incredible; everyone on this date is exemplary, with a true group sensibility taking priority over individual solos (which are of course great). This record is all but inconceivable without Joe Chambers.

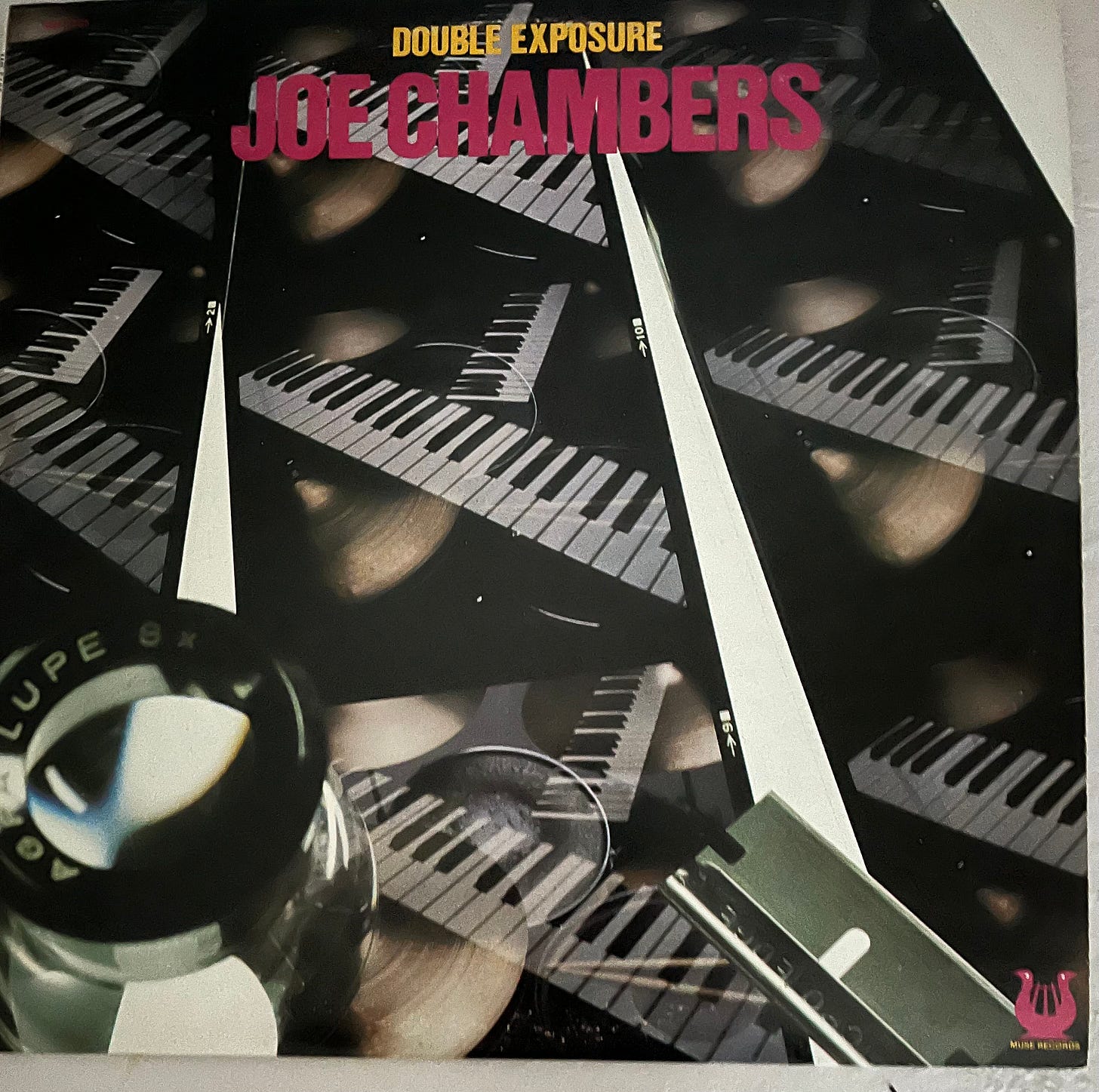

Fast forward to 1978: Muse Records releases a quietly audacious project— a duo recording of Joe Chambers and organist Larry Young. Double Exposure, Chambers’ third leader date, must be one of the great jazz albums of the Seventies. Here’s a link to a vinyl rip, the only place to hear it online.

Beyond being a joy to listen to, it’s an illustration of how accomplished Chambers is— he can inhabit the blended space as a pianist, composer, drummer, arguably even as a record producer. This music sounds and feels so contemporary, almost like a personal project for a Bandcamp-only release.

Throughout, Chambers is telling us: this is composition, free improvisation, and contemporary popular music; these sounds can, should, and do co-exist.

Side One is a ruminative suite featuring Chambers on piano, with Young mostly creating soundscapes and playing texturally. On Side Two, Chambers is on drumset, rocking out with Young.

“Hello To The Wind” is a Chambers’ masterpiece, the meeting place of jazz, pop music, and modern composition. Originally heard with the voice and lyrics of Gene McDaniels on Bobby Hutcherson’s Now!, Chambers opens up the spaces between the sections for rubato, vamping, and dialogue with Young, who is playing magically throughout the session. This track is rhapsodic and confident; just the best.

Young’s “The Orge” is a simple melody built on alternating arpeggiated C major and C minor triads. Chambers and Young never truly leave the melody while Chambers adds some unobtrusive tabla overdubs. “The Orge” fades out on the melody….

.…and then the next track fades in with a reprisal of the melody, before a chord from Chambers sets up “Mind Rain”. Young and Chambers play the melody— sort of AABAC— in loose unison; it's amazing how much groove they generate without bass or drums.5 They find an ending, and Side One is concluded.

Side Two starts with “After The Rain”, not the Coltrane tune, but a semi-improvised Joe Chambers solo piano piece. “Message From Mars”, however, is a Larry Young tune, somewhere between Woody Shaw, the Ventures, and Mahavishnu. Chambers is a great backbeat player— I didn’t find another example of Chambers playing like this— and he sounds like he’s enjoying bashing and rocking, while Young just sticks to script, dishing out the melody and letting the energy build.

The final track is “Rock Pile”, which is “Mind Rain”, but now a rocked-out drums and organ duo. The blended space persists even here— instead of a vicious chops display from Chambers or Young, we just get melody, repeated forever, with some impressive but ultimately composerly licks from Chambers.

Chambers will seemingly never play something that is disconnected from the song, the players, and the moment. Everything he plays matters, has direction and intention. Simply stunning.

Chambers has done so much. As a bonus, here are five tracks that are personal favorites; maybe there’s something here you haven’t heard in a while:

Wayne Shorter: Mephistopheles from The All-Seeing Eye. Chambers alternates between abstraction and groove; he is in the music, essential to the feeling of the piece.

Bobby Hutcherson: Blow Up from Oblique. Bobby, Herbie, Chambers, and bassist Albert Stinson throw down on an echt 60’s track. Chambers lets the tension and groove build, build, and then opens up for maximum effect.

Charles Mingus: E.S.P. from Charles Mingus and Friends In Concert. Chambers swinging a big band, fronted by the original master of the blended space; great to hear Chambers expertly accompany Lee Konitz, Gene Ammons, and others.

Joe Chambers: The Almoravid from The Almoravid. M’Boom adjacent, with Omar Clay and David Friedman; M’Boom later recorded this piece. Chambers takes the blended space into the 70’s on his first leader date.

Stanley Cowell: It Don’t Mean A Thing from Back To The Beautiful. Ellington, Ahmad Jamal, and something from R&B; Chambers is the man for this project.

I’m keeping my eyes out for a Joe Chambers show here in NYC. He and his cohort were far ahead of their time; we’re still digesting his message. He mirrored the musical and social concerns of 2023 in the 60’s— I’m certain he has something to say to us now.

Please leave comments, I want to hear from you— stories about Joe, info I missed, gigs you saw, favorite Joe tracks, etc.

All respect for, and sincere gratitude to, Joe Chambers.

A primal influence on Joe Chambers is his brother Talib Rasul Hakim (born Stephen Chambers), a noted classical composer, best known for his piano piece Sound-Gone and Placements, for percussion and piano. These are incredible pieces and should be heard, both for their own sake, and to broaden our understanding of Chambers and Co.’s milieu.

This list leaves out Chambers’ work with Archie Shepp and with Don Friedman/Jimmy Giuffre, both important associates with whom he was working regularly for periods. Just trying to keep this post to manageable lengths— Archie Shepp cannot be glanced at!

Illustrating Chambers as a member of a group, consider how he and Tony Williams run almost parallel to each other. Surface details like shared deep connections to Max Roach, Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, Richard Davis, Eric Dolphy, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, and Larry Young are suggestive; more intriguing is the fact that Chambers was at one point rehearsing with Lifetime as a percussionist. Williams’ final leader project was 1996’s Wilderness, dedicated to Dr. Olly Wilson, grand master of African American classical music. This is the same Olly Wilson who programmed and recorded Chambers’ brother Talib Rasul Hakim’s music for a 70’s Columbia release dedicated to Black composers. Recently, Chambers’ 2023 Blue Note release, Dance Kobina, features Ira Coleman, Williams’ longtime bassist. And so on.

Max Roach must have sensed this in Chambers when he recruited him for M’Boom. Of course, Chambers, and Tony Williams, and Bobby Hutcherson, were experimenting with percussion duos and trios on Blue Note records; the improvised percussion trio of Herbie Hancock, Bobby Hutcherson, and Tony Williams on “Memory” from Williams’ Life Time; the Hutcherson/Chambers percussion duo on “Bi-Sectional” from Bobby Hutcherson’s Oblique. These two random examples shows how the idea of M’Boom was in the air in 1970; they show how rooted and connected M’Boom was from its moment of inception.

A fragment of “Mind Rain” from Double Exposure was sampled by DJ Premier to create the basic track for Nas’ iconic 1994 single “N.Y. State of Mind”.

I had Chambers on my podcast in 2021; some of what he had to say about free jazz drummers in particular is fascinating: http://www.osirispod.com/episode/burning-ambulance-joe-chambers/

Glad to see I'm not the only one obsessed with that list of recordings from the mid to late 60s (your highlight reel.) It's a mind-blowing body of work. That Hill/Hutcherson/Chambers axis is incredible.