After I grew up and moved to New York City, I abandoned my fandom.

Can you blame me? If you pledge allegiance to Frank Zappa’s Joe’s Garage (1979), it means you like songs about Catholic girls, wet t-shirt contests, and venereal disease, plus anti-music business screeds and eight-minute guitar solos. Had I let on how much I used to love it, I would have been outing myself as a Former Teenage Boy.

On the internet, I’ve seen Joe’s Garage referred to as Zappa’s masterpiece; Rolling Stone even called it his Apocalypse Now in their (sympathetic) review in early 1980. That’s a stretch, but it’s not unreasonable to compare Zappa to Colonel Kurtz. Though he was never a mainstream artist, Zappa, like Kurtz, had a sizable and fanatically devoted following, to whom he was devoted in turn. By maintaining such a fanbase, Zappa was able to release seemingly countless albums— 62 in his lifetime, more than that following his death— and stay on the road, playing major venues pretty much continuously from 1967 to 1988. His rabid fans made the man a fixture of American pop culture.

But in the spring of 1979, Zappa’s career was on the verge of stalling out. His Warner Bros. contract had become tied up in legal wrangling, and his only way forward was extensive touring and self-released albums.

So he set to work. He’d formed a hot new band the previous fall, and had two new songs for a planned single release, hoping to build on the strong sales of Sheik Yerbouti (his first self-release) and prime his audience for another long tour later in the year. Notable new members of Zappa ’79 included vocalist Ike Willis, guitarist Warren Cuccurullo, and legendary drummer Vinnie Colaiuta in his recording debut. (Colaiuta in particular shines on Joe’s Garage; for Vinnie’s playing alone, the album has been a favorite among drummers for decades.)

During what was planned as a two-day, two-song (“Catholic Girls” and “Joe’s Garage”) recording session, one thing led to another, and soon the band was tracking master takes of anything Zappa threw at them: recent compositions, odd-meter vamps, new arrangements of old tunes, improvs, guitar solos.

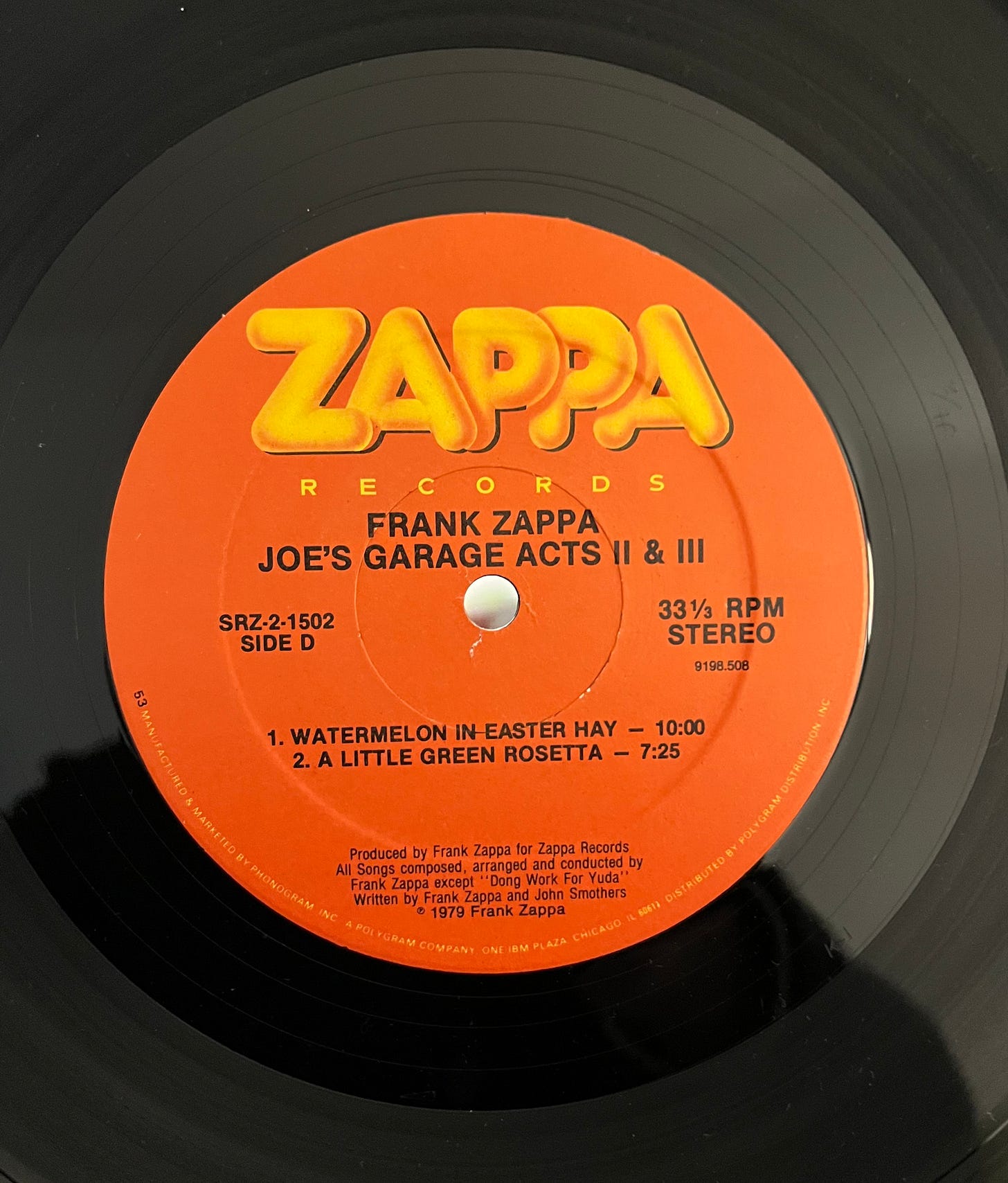

When the sessions ended weeks later, nearly 20 new titles were ready for release, and Zappa came up with the flimsiest of storylines, in three acts, to tie them together. He overdubbed a third-person narrator he called “The Central Scrutinizer”, dusted off some old cover art (images that are beyond the pale in 2024) and voila, Joe’s Garage was unleashed upon the world (Act I was released as a single LP in September ’79, Acts II and III as a double LP in November).

Zappa started featuring the songs in concert immediately, and kept a few in rotation for the rest of his touring career. Though only a modest hit on the pop charts, Joe’s Garage was a huge success in Zappa’s universe, setting the stage for his own third act in the Eighties as part elder statesmen, part media hound, part old crank.

In retrospect, it’s strange that the album connected with listeners so well. The thing only barely hangs together.

It starts strong. “Joe’s Garage”, the title track and the first proper song on the album, is an unabashedly nostalgic and sweet story of kids forming a band, with the subject matter, harmonica intro, and gentle melody making the song Springsteen-adjacent. The next track, “Catholic Girls”, is probably the album’s most notorious— tasteless, crass, and deeply goofy, a Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker spoof in song. It’s rude, to be sure, but it’s not mean-spirited. When my father heard me listening to it, he laughed and said that the jokes were the same ones he’d heard as an Italian-American Catholic teenager in the Sixties.

After those two highlights— as good an encapsulation of Zappa’s social role in pop culture as any— the album takes a strong turn for the worse. “Crew Slut” is downbeat and unfunny, a dreary dirty blues that eventually becomes the aural equivalent of meaningless sex. When we get to “Fembot In A Wet T-Shirt”, with its pitch-perfect smooth jazz and clinical depiction of a night of fake sex, the clouds that first appeared over “Crew Slut” darken.

What’s left of the album is a deluge of hodgepodge. There’s lots of old songs Zappa had laying around (“Lucille Has Messed My Mind Up” is from 1969, “Stick It Out” from 1970, “A Token Of My Extreme”, 1974, “Keep It Greasey”, 1975); a few bona-fide new tunes (“Sy Borg”, “Packard Goose”); and guitar solos excerpted from live recordings (“He Used To Cut The Grass”, the coda of “Keep It Greasey”, et cetera). Finally, on Side 6, we get a long instrumental, “Watermelon In Easter Hay”, and a fun throwaway, “A Little Green Rosetta”, bringing the album to a close.

And that’s pretty much it. Viewed from this angle, Joe’s Garage is juvenile, offensive, emotionally stunted, prurient, dated, preachy, goes on forever, and makes no sense. For a 3-LP, big-idea concept album, it doesn’t really cohere— it’s merely the best music from what must have been a fun month in a recording studio rush-released to boost Zappa’s touring career, his only reliable source of income at the time.

Who would want to listen to this? Why would a person need such a thing? Who besides a teenage boy from an earlier, far less enlightened era, would care about this nonsense?

Me, as it turns out.

I first heard Zappa as a 10 year old, when “Peaches En Regalia” was on a tape my father made for me. I’d never heard anything so cool. It was dizzyingly complex and utterly delightful. The beat was great, the drums were loud, it was a perfect kaleidoscope of sound— everything just kept moving around. I used to lie on the bedroom floor and put the cassette in my tape player and listen to “Peaches En Regalia” over and over and wonder— who is this Frank Zappa character?

In my early teens, I got ahold of some his other records— Apostrophe (1974), We’re Only In It For The Money (1968), Burnt Weeny Sandwich (1970), Sheik Yerbouti (1979), others— and was soon enthralled. Zappa’s music and persona seemed the apex of creativity, individuality, and freedom.

And Zappa really made you want to be a musician. So it made perfect sense when I met some older guys through school band who were into Zappa like I was. On the outskirts of that group was Mike1, an intellectually voracious 17 year-old whose homosexuality was an open secret, a brave move in our small, mostly rural town outside Utica, NY. One day after school Mike stopped me in the hallway and laid the (‘87 Rykodisc) two-CD set of Joe’s Garage in my grubby 14 year-old hands. “This is the one you need to hear”, he said, and strode off smiling, his work here done. I went home and put it on, and as usual with Zappa, I was initially baffled, but laughing and intrigued. Soon, I was onboard, and Joe’s Garage became a favorite.

But time passed, priorities shifted, and I gravitated, happily, towards learning and playing jazz. When I moved to Brooklyn after college, a 22 year-old wannabe jazz musician, it was the end of a long goodbye to Zappa and the close ties of that particular friend group. Adult life and professional accomplishment beckoned, and in this, Zappa, especially the Zappa of Joe’s Garage, had no room.

It was time to be someone else. Time to put away all that stuff, move past those records, and besides, isn’t Zappa truly offensive anyway?

Some have noticed that behind the dirty jokes and music-business rage of Joe’s Garage lies a great deal of sadness. After all, Joe is jailed and released into a world where music is illegal. Since he’s not allowed to play, he lies in bed and dreams music until he eventually gives up entirely and gets a job making baubles in an assembly line.

I’d go further. Joe’s Garage is a hot mess, but hangs together because the songs aren’t just telling a sad story, but because the album is—thematically, lyrically, and emotionally— all about failure.

It’s failure that animates the two great guitar solos at the heart of Joe’s Garage: “Outside Now” and “Watermelon In Easter Hay”. These two sturdy, resilient depictions of isolation, self-pity, and acceptance are the key to hearing what Zappa was trying to do on Joe’s Garage, maybe even with his music as a whole. “Outside Now” and “Watermelon In Easter Hay” are, at their core, the blues.

In “Outside Now”, vocalist Ike Willis as Joe, our musician protagonist, describes surviving life in prison with “imaginary notes” his only solace. “Watermelon In Easter Hay”, an instrumental, is the last music Joe makes— not played, just dreamt— before joining the assembly line.

The two tunes are similarly constructed: an asymmetrical melodic line played in an even, unvaried pulse serves as the spine of both songs. “Outside Now” is maybe G dorian, maybe Bb lydian, in 11/8, while “Easter Hay”, the only guitar solo on the record that Frank performed with the band in real time (all the others were from road tapes, with the studio band overdubbing) is E major in 9/4.

Zappa wasn’t particularly in my head last summer, but I had failure on my mind for sure. I’d just moved out of the apartment I’d shared with my wife, and at age 43, was now on the other side of a union I’d thought and hoped would persist.

It was time to get the last of my stuff out of her place, formerly our place. When I first left in the winter, I held on to a glimmer of hope that this was temporary, and leaving some things was my way, I guess, of expressing that hope. But no, this was it. Get the last stuff out, file the papers. It’s over.

She was great about it, and really, so was I— promptly responding to all texts and emails, helpful and courteous on the day-of. While we weren’t exactly friends, there was no enmity for her from me, and I felt none from her. This was awful for both of us, no need to make it worse by being unpleasant.

So I walked over, 10 blocks in Brooklyn, went in the lobby that had been our lobby, and gathered all my things, a lot more than I realized.

I could feel something like care in how she packed and stacked everything, almost as if she was thinking about what would be easiest for me to carry, or best for me to unpack. Her easy thoughtfulness, coupled with the knowledge that we cannot and would not be together, made my simple task all the more heartbreaking.

Heartbreaking, and arduous: gathering up the boxes, calling the cab, seeing an acquaintance who didn’t know, explaining “yes, we’re getting divorced”, standing there with my detritus. No one wants to do what I was doing.

Through it all, one song was screaming through my head, a steady companion, holding my hand and helping out. It was a song I hadn’t listened to or thought about in years: Frank Zappa’s “Watermelon In Easter Hay” from Joe’s Garage. Out of nowhere, there it was, unbidden and unrequested, broadcast live in sparkling fidelity from my subconscious, getting me through the final moments of a dead marriage.

Four descending and five ascending notes, like an out-breath, and longer in-breath with a yearning, major-key melody hinting at the lydian mode, and then a left-field blues lick that somehow ties the whole melody together. That song was my best friend that day.

A fellow Zappaphile suggested that the metaphor of a watermelon growing in Easter hay— an awkward and fuzzy one, to be sure— is Zappa’s depiction of an artist in society. That works, though the title was, characteristically, a band in-joke about Vinnie Colaiuta: “Soloing with this drummer is like trying to grow a watermelon in Easter hay!”, or something along those lines. But maybe Zappa meant something even more universal— maybe he meant a human being in the world.

That’s what I was that day. Carrying those boxes, sitting in the cab, with “Watermelon In Easter Hay” on repeat in my head, I learned something about Zappa’s music, and about my own life. I was whomped on the forehead with how common my situation was, how absolutely ordinary I really was, had always been. I felt like I had something in common with all of humanity.

At the same moment, I heard, clear as day, the depth of emotion in Zappa’s music. There it was, sitting underneath sex jokes, arrogance, and fantasy, singing out loud and clear: a luminous warm acceptance: the humor, truth, and resilience of the blues. It was Frank’s blues that I connected with. Beneath the surface noise of his music beat a wise and generous heart.

I realized that Zappa had been playing the blues all along; as for myself, I really had the blues now. Actually, I’d always had them, and I understood, viscerally, in that moment, that everyone has the blues: it is the human condition.

No course of therapy or meditation can take the blues away, no amount of money or sexual experience can erase them. You are born to be blue, alone, and you will die, alone, with the blues. But keep those blues, cause you’re gonna need them— it’s the thing that will connect you to anyone and everyone.

That’s what Zappa played, that’s what meant so much to me as a teen, and it was bolstering me up now. It took some grown-ass adult failure for me to realize that I loved Zappa’s music, that it was connected to everything I care about.

As I carried those boxes to the cab, and then to my apartment, it was obvious: that personal transformation I’d dreamed of when I moved to Brooklyn? That dream of becoming someone else? It never happened, and never will happen. I’m still me, Former Teenage Boy.

And, you know, Joe’s Garage might be a mess, but it’s a lot of fun, even a hit— I’m thinking of a few folks I’ve put it on for recently who really dug it. Listen closely and you can hear how hard Zappa worked to make a record you would enjoy.

As offensive as Joe’s Garage surely is— was intended to be— it’s also deeply silly, even downright goofy. How can I work up indignant 2020s Brooklyn anger when Zappa is just being a zany uncensored goofball, when he is simply being himself? And when it’s not the dorkiest high school music ever, Joe’s Garage is imbued with sadness— perhaps of the teenage boy variety, but the sadness of a teenage boy is sadness nonetheless.

For all its faults and excesses, Joe’s Garage realizes its purpose as a pop music artifact— a set of songs that can become a part of your life. If you love it, you can imbue it with personal meaning, and if you so choose, it is yours for the rest of your days, connecting you to the many folks who love it too. Mission accomplished.

I was in Portugal when I heard that Mike, who’d palmed Joe’s Garage off on me when I was 14, had just died, age 46. He’d gone down a hard road since the days of our Zappa-fueled friendship— addiction, financial problems, failed relationships, serious illness. He lost his beloved parents, one after the other, in quick succession in 2018, and now he’d slipped away quietly in our home town.

We’d been distant for decades, but I felt the loss just the same. The last time we’d exchanged messages, in 2019, Mike was still enthralled with Zappa’s music; I’m glad we had something to talk about one last time. Love and respect2.

Not his real name. I changed it to protect the innocent.

Special thanks to Shuja Hader, Jonathan Finlayson, Ethan Iverson, and Mark and Zoe Sperrazza for edits and encouragement.

Great essay Vin. Bravo

Beautiful essay, Vinnie - Thanks!

I have been a huge fan of Zappa, but have also long been frustrated by the dichotomy between outstanding musical creativity on the one hand and the barely-in-High School theatrical aspects… I saw Zappa and the so-called ‘New Mothers’, booked by Bill graham at Winterland in San Francisco, on New Year’s weekend in (I think) 1972-73 (I was 19). The band was Jean-Luc Ponty, Ian and Ruth Underwood, George Duke, Ralph Humphrey, and Tom & Bruce Fowler. There was no singing, and no theatricals - they played two sets, two and one half hours each - all instrumental music of great power. The set list was of the Hot Rats-Grand Wazoo era, with some foreshadowing of songs that didn’t hit the rotation until later, like Inca Roads.

They stretched out, to say the least. Frank conducted the band with hand signals, and the band turned on a dime during complex ensemble passages. The highlight for me was Frank playing mallet duets with Ruth Underwood. To say I was blown away is an understatement, and I looked for (and hoped for) future bands and albums that took this path… There were glimpses in later albums such as Live in New York, but I came to feel it was (for Frank) a road increasingly not traveled. There was a lot of other music in the air, and eventually I found everything I was looking for in jazz and classical musics of that time… But I will always remember that concert, and the overwhelming effect it had on me. Your essay brought back these memories...