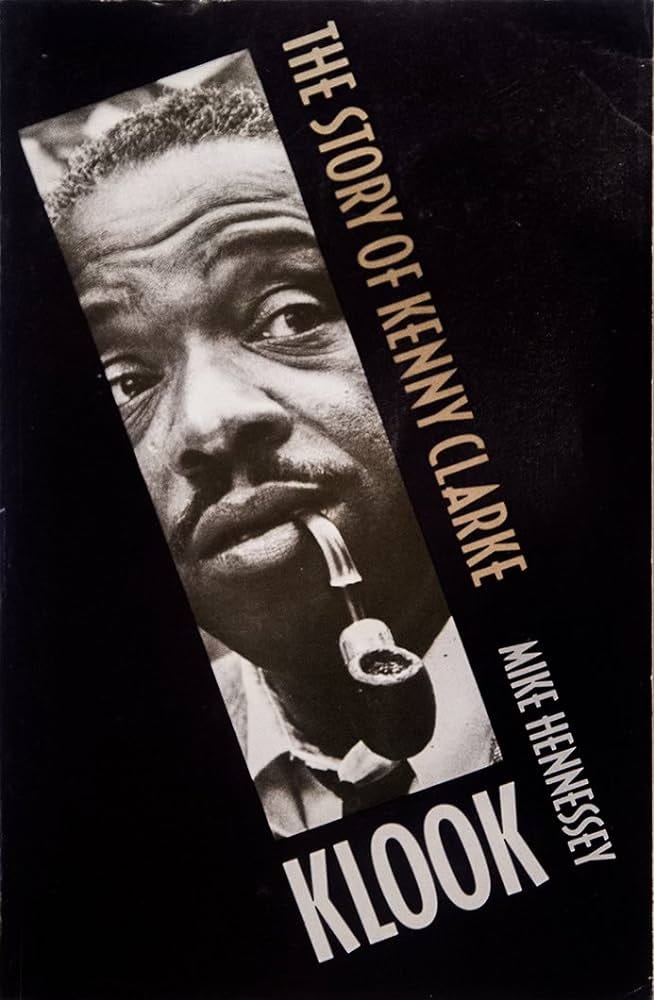

Klook: The Story Of Kenny Clarke

A look at Mike Hennessy's great biography of the legendary drummer.

It dawned on me that drummer Kenny Clarke is a co-author of three essential songs in the jazz repertoire. Like so much about Clarke, this simple fact feels hidden in plain sight:

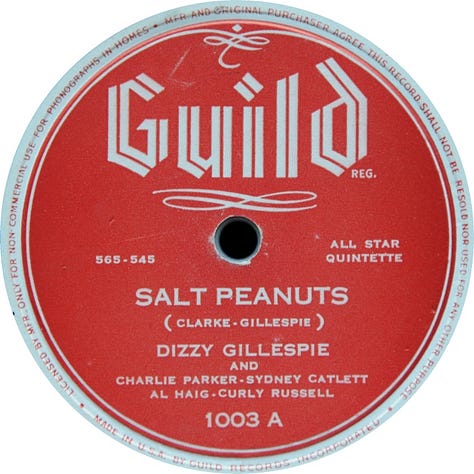

“Salt Peanuts”, by Dizzy Gillespie and Kenny Clarke, copyright 1941;

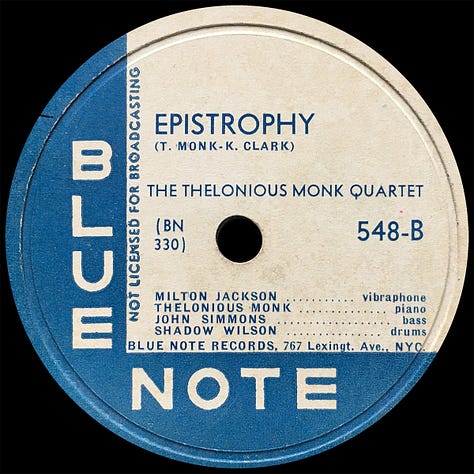

“Epistrophy” a.k.a. “Fly Right”, by Thelonious Monk and Kenny Clarke, copyright 1941;

“Rue Chaptal” a.k.a. “Royal Roost”, a.k.a. “Sportin’ Life”, a.k.a. “Tenor Madness”, by Fats Navarro and Kenny Clarke, first recording 1946.

This sort of summarizes Kenny Clarke’s importance. No other drummer has their hand in the repertoire to this extent.

Mike Hennessy was a British pianist and journalist who wrote for Billboard. He and Kenny Clarke became friends in the early Sixties, and when Clarke died, Hennessy was already at work on what would become Klook: The Story of Kenny Clarke. Published in 1990, Klook is a full-length Kenny Clarke biography, well-researched, sensitive, and honest1. Hennessy’s affection and admiration for his subject informs every sentence, yet he’s forthright and direct about Clarke, chronicling both his huge musical contribution and professional successes, as well as Clarke’s drug addiction and struggles with his oldest son, Toby.

Kenneth Clarke Spearman— Hennessy is very specific about this, taking pains to show that this is Clarke’s birth name— was, according to the documents, born on January 9th, 19142, in Pittsburgh, PA, the youngest of two boys to father Charles Spearman and mother Martha Grace Scott. It was Clarke’s mother who introduced him to music, showing him hymns and spirituals at the piano.

Clarke’s father left early on, moving to Yakima, WA and starting another family. Soon after, Clarke’s mother took up with— and possibly married— a man Kenny described as a “Baptist preacher”. When Kenny’s mother died (before Kenny’s 7th birthday), he and his brother were placed in the Coleman Industrial Home, which was essentially an orphanage for Black children in Pittsburgh. It’s here, under the guidance of a man Kenny remembered as “Mr. Moore”, that Clarke begins playing drums.

After leaving the orphanage at age 11, Hennessy tracks Clarke to five different home addresses over four years. Finally, at age 15 (in 1930), Kenny, then living with the Baptist preacher, was thrown out, allegedly for rooting through the preacher’s desk in search of a photo of his mother. Clarke, living briefly with foster parents and working odd jobs to support himself, was drawn to show business.

Clarke was a fully-employed professional drummer by 1931, based in Pittsburgh and working around the Midwest. He heard the top bands of the era— Luncford, Henderson, and especially Ellington— up-close and repeatedly, which must have given some ideas about how the drums should be played. With the support of Mary Lou Williams and road experience with Roy Eldridge, Clarke’s reputation was steadily rising.

Kenny was 21 in 1935, the year he moved to NYC with pianist Call Cobbs3. A year later, at a club in Greenwich Village, Klook, bassist Frank Clarke (Kenny’s half-brother), pianist Fats Atkins, and guitarist Freddie Green (later of Count Basie, whom he joined in 1937) were the rhythm section for tenor saxophonist Lonnie Simmons’s band.

Clarke on the Lonnie Simmons band:

“What a band that was…..the word got around and we used to have a lot top musicians come in to hear us— Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa, Teddy Wilson… Freddie Green and I got something going with Lonnie’s band, long before the new rhythmic approach to playing drums was noticed….Basie was knocked out at the way the rhythm section was jumping and I’m convinced he changed his piano style after hearing Fats Atkins.

-Kenny Clarke in Klook: The Story of Kenny Clarke

Stunning to realize that Basie’s ideas about the rhythm section were informed by Kenny Clarke!

Klook goes from Lonnie Simmons’s group to Edgar Hayes’s (where, as I’ve mentioned earlier, he played on the original “In The Mood”), to Teddy Hill’s orchestra. It was Teddy Hill who asked Kenny to be the leader of the house band at Minton’s Playhouse, in early 1941. It’s at Minton’s, with Thelonious Monk and a host of guests, that Clarke makes his statement. I’ve told a little of that story here.

By now, Kenny was in a relationship with a young Carmen McRae, who wasn’t yet working as a singer. In the spring of 1943, he was drafted for the war effort. Clarke and McRae were married in the summer of ‘44, and that fall, Clarke, age 30, was sent overseas with the US Army. While stationed in France, Klook stopped playing drums, instead opting for trombone and singing in a men’s choir alongside his new army buddy, pianist John Lewis.

Clarke was discharged in early 1946, and encouraged by Dizzy Gillespie, began playing drums again. While living in Brooklyn with McRae and her parents that spring, Clarke joined the brand-new Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra, with arrangements by Walter “Gil” Fuller, and, on Kenny’s recommendation, John Lewis. Kenny recorded and toured with Gillespie on and off until 1948, by which time he’d converted to Islam, taking the name Liaquat Ali Salaam.

There’s a record of Clarke playing with the Miles Davis-Tadd Dameron Quintet at the Salle Playel as part of the Paris Jazz Festival; it’s startling to hear a crowd of 3,000 screaming in ecstasy for Miles, Tadd, James Moody, and Kenny Clarke. It was after this festival that Clarke decided not to go back to NYC, opting instead to stay in Paris, where he gave workshops and played gigs. His marriage to McRae had dissolved, and Klook was now in a relationship with vocalist Annie Ross (of “Twisted” and Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross).

In December 1950, Ross gave birth to their son, Kenny Clarke Jr., called Toby, who was raised not by Kenny and Annie Ross, but by Kenny’s brother’s family in Pittsburgh. Hennessy is unflinching as he describes Toby’s troubled early life and teen years, for which Klook was quite absent.

In 1951, Clarke returned to NYC, and within weeks, was busy in the clubs and recording studios; Clarke even had a salaried A&R position at Savoy Records. It is from this time and place— NYC, August 1951 until late 1956— that many of Clarke’s well-known recordings originate: Walkin’ and Bags’ Groove with Miles Davis; Django by the Modern Jazz Quartet, of which Klook was a founding member, and classic sessions led by Milt Jackson, Hank Jones, Hank Mobley, J. J. Johnson, and others.

Though he was a success in New York, Clarke was, evidently, unsatisfied. Accepting an offer for a full-time gig in Europe with French bandleader Jacques Helian in late 1956, Kenny Clarke left the United States for Paris, never to live in his birth country again.

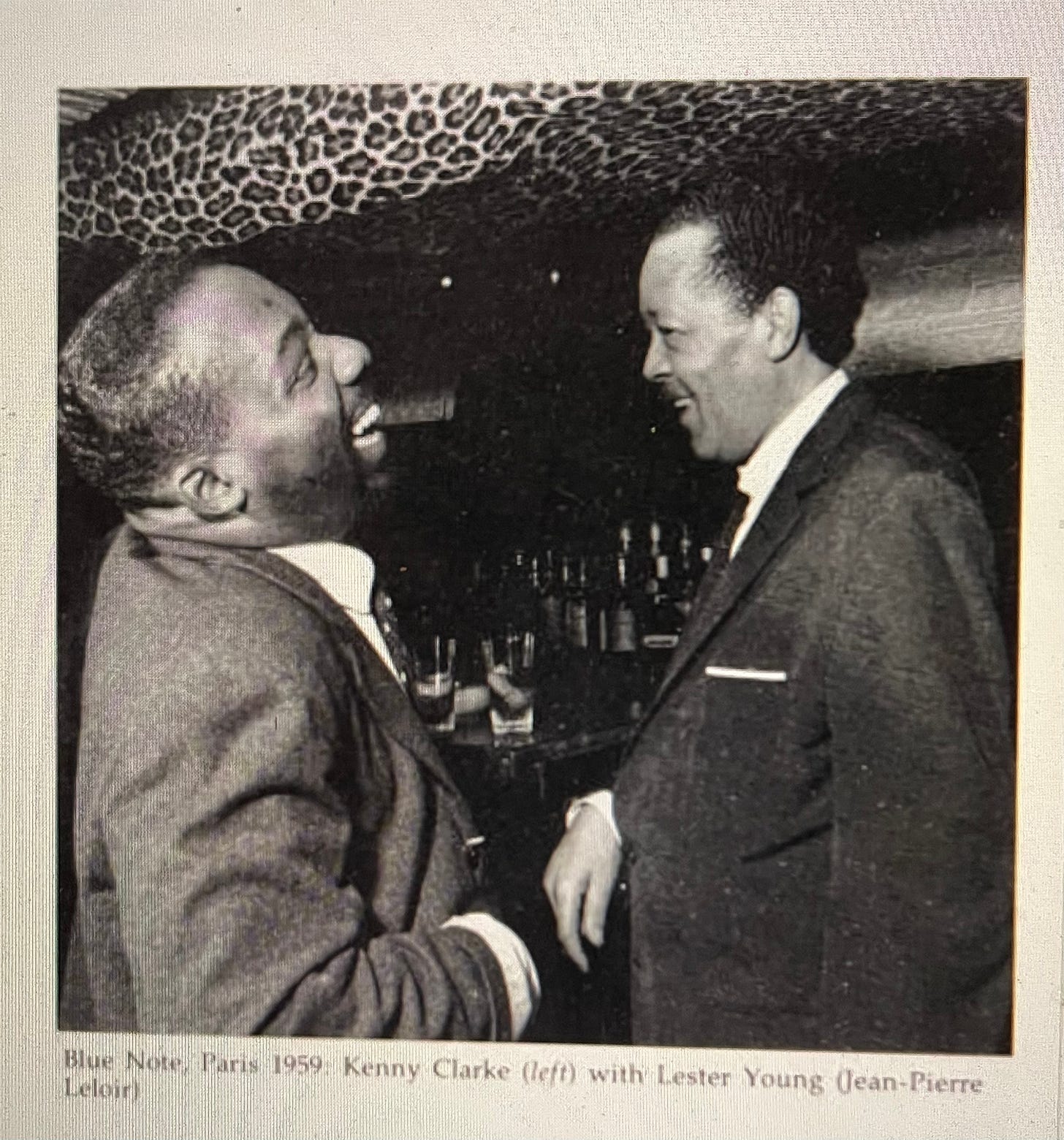

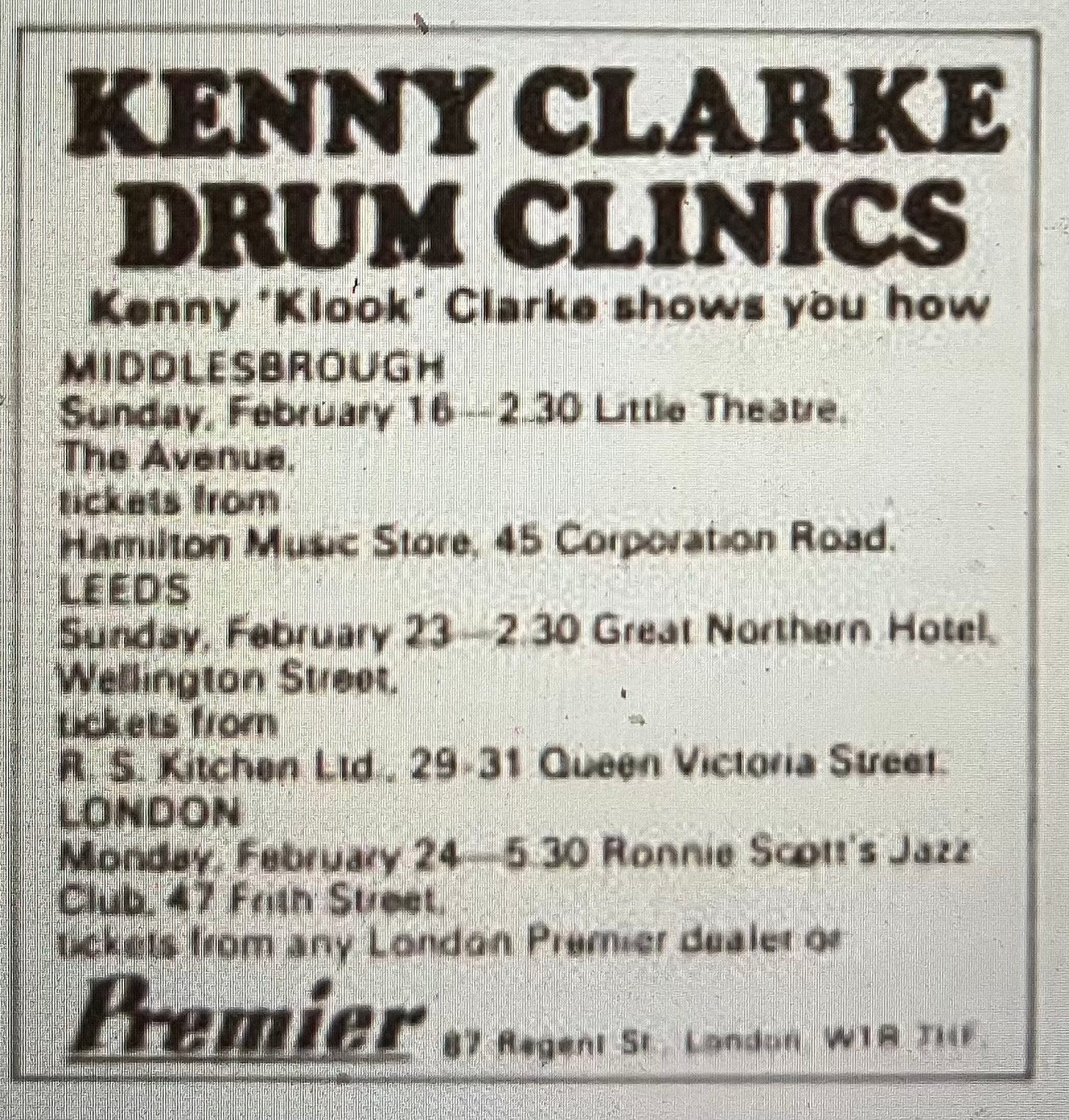

In France, Clarke thrived. Seemingly overnight, he became a respected and feted fixture of the Paris jazz scene. First at the Club de St. Germain, in a trio with Martial Solal, then at the Blue Note with Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke was a star attraction in the City of Lights. Klook worked constantly— tours, record dates, and workshops at colleges, culminating in the formation of the Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band.

Backed by restauranteur, promoter, and avid jazz fan Gigi Campi, the Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland band became the premier European jazz group of the Sixties, sort of the Continental answer to the Thad Jones and Mel Lewis. The Clarke-Boland group started as an octet (“The Golden Eight”) and released their first album on Blue Note (not currently streaming on Apple Music) in 1961. By the mid-Sixties, it had swelled to a big band, often featuring Johnny Griffin and trumpeter Benny Bailey. The band was a sensation. Even the quick audition I gave to Volcano (Polydor), recorded live at Ronnie Scott’s in 1969, was enough to convince me how exciting and fun the band was.

In the Seventies, Clarke went at a slower pace. He was now in his mid-fifties, drug-free for the first time in over a decade, (Hennessy reports that Klook had been a heroin addict since the late Forties), living in a Parisian suburb, married to Daisy, and a father to Laurent (born August 4, 1964). He made some appearances at European jazz festivals, booked the occasional record date, received lots of honorary awards, and even made a few quick trips back to the States, but that was about it. Overall, Hennessy reports that Clarke was content at this point to teach at the Kenny Clarke Drum School (housed at the Selmer factory in Paris), raise his son, and tend his garden.

In January 1985, as Clarke and Hennessy were making plans to put together a Paris Jazz All-Stars group featuring Clarke, Johnny Griffin, Woody Shaw and others for a summer tour and recording, Kenny Clarke suffered a heart attack and died at his home. He was given a send-off fitting a Continental eminence in his adopted France, but Hennessy is unsurprised to report that the New York Times thought his death merited no more than three paragraphs.

Fun photos from Klook:

Klook is just so great, so helpful. Hennessy’s biography goes the distance to establish Clarke’s primacy, gives context for Klook’s musical achievement, and lets us glimpse the human being who made such daring choices. The overall impression is clear: modern jazz was made in Clarke’s image.

More to come from Chronicles as I learn more about Clarke’s contribution. Now that I have his life (sort of) in front of me thanks to Hennessy’s book, I can see all the periods I want to focus on:

Klook’s work with John Lewis;

In NYC with Kenny Clarke, 1951-1956, with a special emphasis on Miles Davis’s seminal 1954 sessions, for which Clarke is essential;

In Europe with Kenny Clarke, with a special look at the Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland big band.

This is a long-term project; I’ll be going carefully. In a few minutes, I’m going to join Ethan Iverson and the Mark Morris Music Ensemble for a performance of The Look of Love here in Philadelphia. I’ll be thinking about Kenny Clarke.

It’s unfortunately out of print, and even a used copy runs between $75-$100 dollars on all the usual sites. Thankfully, the Internet Archive digitized the book in 2022, where it can be read for free with a signup.

Hennessy reports that another source, author Ursula Broschke Davis who interviewed Clarke, claims that he was born on January 2nd, 1914.

Is this the Call Cobbs from Albert Ayler’s Love Cry and New Grass? If Wiki is to be believed, it is, as Cobbs was born in 1911, making him three years older than Clarke.

It's the same Call Cobbs. The club where Basie heard Kenny Clarke was the Black Cat, a former speakeasy-restaurant on the east side of what is now LaGuardia Place (then West Broadway) just south of Third Street, where the elevated train turned south. John Hammond lived on McDougal Street, and he frequented the place, which was Mafia. Hammond brought all the people you mention, including Basie, who he thought should hear Freddie Greene...we know the rest of that story.

Very glad you mention “Epistrophy” as a Clarke co-composition! I’ve always thought that that song, in particular, shows how Klook’s off-kilter “cutting the time up” contoured the whole bebop movement. It’s right theee in the melodic accents.

Also, the story in Hennessy’s book of Klook smoking pot with Louis Armstrong is one of my favorites.