Listening to Forces of Nature

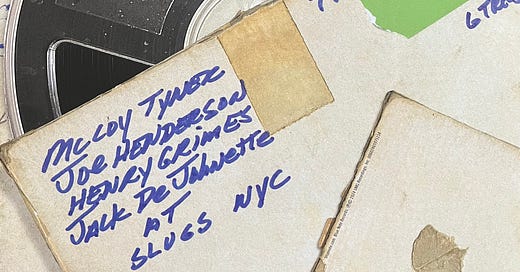

McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, Henry Grimes, and Jack DeJohnette in 1966

I’ve been excited about Forces of Nature, the Blue Note release of a gig by McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, Henry Grimes, and Jack DeJohnette, at Slugs Saloon in 1966, since September. My copy arrived early last week, a day after its official release.

I listened throughout the Thanksgiving weekend, and just loved it, got really into it— it’s intense, fresh, inventive, and constantly surprising me; every few minutes I’d hear something and think “I’ve never heard [Tyner, Joe, Jack, or Henry Grimes] play that before!” It’s something to be truly thankful for. Hold the LP package in your hands, and Forces of Nature feels like a celebration of, and tribute to, McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, Henry Grimes, and Jack DeJohnette.

We’re so lucky to have this music.

Forces of Nature puts Slugs’ front and center, giving us a chance to appreciate the strength of the jazz community in the Sixties, when the music suffered a drastic commercial downturn. Those hands we hear clapping are the people who supported McCoy Tyner and Joe Henderson before they were jazz superstars, folks who did their part to keep the music going. Respect.

The album came about when Orville O’Brien, a recording engineer affiliated with Town Sound Studios, a Black-owned recording studio in Englewood, NJ, lugged his reel-to-reel tape recorder to Slugs’ and recorded a McCoy Tyner/Joe Henderson gig. He gave a copy to Jack DeJohnette, who kept it in his archives for years, and now it’s ours to hear. For more on this, I recommend read Nate Chinen’s great Substack post; there’s also this quick, enjoyable conversation between Don Was and Jack DeJohnette for more background.

For some reception history, I revisited Ethan Iverson’s “McCoy Tyner’s Revolution” from December 11th, 2018— Tyner’s 80th birthday. In his great piece, Ethan explores many aspects of McCoy’s music and influence, showing just how radical Tyner’s conception was, how it immediately changed the overall sound of jazz. Iverson then includes jpegs of Tyner’s Downbeat reviews from the Sixties, most of which are good. But not one critic seems aware of Tyner’s import. To them, he’s a good piano player.

As far as Iverson could tell, The Real McCoy— the studio document most similar to Forces of Nature— was not reviewed by Downbeat. When, in 1968, Downbeat reviewed Tyner’s Tender Moments, the follow-up to The Real McCoy, it was paired with Herbie’s Speak Like A Child. I was startled by the reviewer’s lack of sympathy for Hancock and McCoy: Speak Like A Child got two stars, and Tender Moments got three.

If the overall impression of these reviews are any indication— and I’m pretty sure they are— then we can say that in the late Sixties, McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, et al, were playing to a small group of hardcore supporters, a few fans, and vast continents of indifference.

In 1966, Tyner wasn’t yet a full-time, year-round bandleader. Drummer Alphonse Mouzon, profiled by the late, great Dan Morgenstern in the March 15, 1973 edition of Downbeat (the interview seems to have been conducted in 1972), hints that only recently was McCoy able to work year-round.

Morgenstern’s article on the drummer includes a few nice details about McCoy— Mouzon explains that Tyner was currently without a manager, booking all his gigs himself; describes Tyner’s gift for getting great sounds from the worst pianos; and suggests the centrality of McCoy’s religious practice to Tyner’s strength and dignity. Mouzon then contrasts McCoy with his previous gig as the first drummer in Weather Report, who were more successful, higher-profile, and critically acclaimed than McCoy:

“[With McCoy] We just play, there’s no great preparation to get ready, no tension. The music is so intense; like in Africa. It’s really going back to the roots, which I needed, because playing with Weather Report was sort of draining…

With McCoy the music— it’s so-called jazz, but I consider it Black cultural music— gave me the opportunity to get into a lot more rhythms, a lot of 6/4, 6/8, which I wasn’t doing with Weather Report, which was kind of Europeanish, rockish, Miles-ish kind of thing...

[Weather Report] is a good group, but it’s hard when you have three leaders telling you what to play, [whereas McCoy’s group] is very close— no ego…with McCoy I can see the light, it’s so spiritual…”

-Alphonse Mouzon

Christian McBride’s heartfelt remembrance of McCoy shows how the jazz community of Philadelphia (McCoy and McBride’s hometown) had long understood Tyner. Early on, the older musicians pressed upon Christian that Tyner was much more than “Coltrane’s pianist”; McBride and his cohort have always seen McCoy as an innovator and composer with a language of his own, a complete identity which includes, but is separate from, his years with John Coltrane.

McBride learns about McCoy Tyner as a complete universe, Iverson shows how little the jazz press understood McCoy, Alphonse Mouzon describes a resolute musician with a mission beyond recognition and praise, and Forces of Nature, the only document we have of McCoy as a leader between Plays Duke Ellington from 1964 and The Real McCoy in April 1967, speaks for itself.

Jack DeJohnette knew, the musicians have long known, and thanks to Forces of Nature, I’m starting to get it: McCoy Tyner and Joe Henderson are two of the greatest ever, deserving of their own chapters in the history of the music. They were not addendums or even “major influences”: they were revolutionary innovators and complete sound worlds. They made as important a contribution as any of the greatest.

In 1966, the East Village, where Slugs’ was located, was funky, even occasionally unsafe in a way that’s hard for us to picture now. The room itself seems to have been adequate— a bandstand, an upright piano, a bar, and sawdust on the floor, enough to do a gig. DeJohnette mentions seeing quite a few fights break out, finding the name “Slugs” quite appropriate. In all, Slugs’ could be affectionately called a dump, but as Richard Davis says, “a dump can be a paradise”.

Ok. We’re at Slugs’, it’s 1966. McCoy Tyner, age 27, has left the Coltrane Quartet— arguably the greatest jazz group of all time— has no recording contract, no critic championing his cause, no support beyond the musicians and listeners.

Tonight, Tyner’s leading a group featuring Joe Henderson, age 29, who had been with Horace Silver since 1964. Henderson has recently left Silver’s band, and we can assume that Joe Henderson, despite having already made albums we now regard as masterpieces, was even less noticed by the jazz industry of 1966 than McCoy.

Bassist Henry Grimes, age 30, goes back with Tyner to 1962 and is currently active in the avant-garde. Later that year, Grimes plays on Blue Note sessions led by Cecil Taylor (Unit Structures and Conquistador) and Don Cherry (Symphony For Improvisers and Where Is Brooklyn). But by 1967, Grimes had dropped out of music completely, and wouldn’t be heard from again until 2003.

On drums is Chicago native Jack DeJohnette, age 231 new to town, recently playing with Jackie McLean. This is DeJohnette before Charles Lloyd, Miles Davis, and ECM, front and center, the youngest and least-recorded of the quartet.

McCoy Tyner and Joe Henderson didn’t plan on recording an album that night. I don’t think they’d program four blues pieces if they knew that folks would be poring over the music the way I am now. Nevertheless, the album is here, and I love it, so let’s listen to Forces of Nature.

“In and Out” (Henderson). Hot out of the gate, Henderson is endlessly inventive, his solo a marvel of sustained creativity. McCoy, playing a not-terribly-in-tune upright piano, and comping very strangely, eventually lets the trio of Grimes, DeJohnette, and Henderson reach the top of the mountain on their own. Tyner’s own solo must be some of the greatest, most inventive, authentic jazz piano ever recorded. Like all of us, I was spellbound the first time I heard this solo.

DeJohnette, on a four-piece kit with a low-pitched, dry ride cymbal, and medium-pitched crash, is feeding the fire, challenging and celebrating the soloists. Elvin Jones and Tony Williams (Jack’s junior by 3 years) are the obvious references, but Jack has his own voice. His ride cymbal is the center of his sound, but Jack’s left hand and feet just get into this stuff that’s more or less impossible to notate, creating a texture that’s both grounding and polyrhythmic. I love how clearly he marks the 12-bar form at moments of peak intensity. Why disguise it?

“We’ll Be Together Again” (Music by Carl T. Fisher, lyrics by Frankie Laine). When McCoy starts the melody (“no tears”), he sounds just like Red Garland, shades of his Nights of Ballad and Blues (Impulse, 1962), while Henderson, inventive as ever, goes in for a hint of that late-night feeling. What a great track— Jack on brushes all the way, and nice to get a Henry Grimes solo. Henderson takes the bridge out, concise and professional.

“Taking Off” (Tyner/Henderson/Grimes/DeJohnette). According to Jack, McCoy and Joe said “Let’s just play some minor blues”, and this was the result, 28 minutes of relentless, freewheeling modern jazz that starts fast and gets faster. As DeJohnette says of this track, “Everyone’s playing like their life depended on it.” Amen. Some minor distortion on the recording feels like part of the scene. There’s some things Jack plays here that I’ve really never heard— unisons with Joe and McCoy, long stretches of three eighth notes, et cetera. Those emphatic snare/crash cymbal unisons with floor tom/bass drum rumbles in his solo will be with me forever.

“The Believer” (Tyner). After the searing intensity of “Taking Off”, things cool off while maintaining the overall vibe. First up is Tyner’s “The Believer”, first recorded by John Coltrane in 1958, two years before Tyner joined Coltrane’s group. It’s a swinging 3/4 blues, and Jack’s four-bar intro makes me think of Elvin Jones’s immortal intro to “India”. Joe and McCoy are just as inventive and revolutionary in a straight-ahead groove. It’s lovely to hear McCoy and DeJohnette find some unisons at a more leisurely pace.

“Isotope” (Henderson). This is the track that came out on the streaming services in September and got us all so excited. In the liner notes, Terri Lyne Carrington highlights DeJohnette’s comparatively ‘tight’ cymbal beat on this cut: if the cymbal beat is ‘ding-a-ding’, Jack’s ‘a’ is close to the second ‘ding’, almost ‘ding-ading’. (Later, his cymbal beat was more broad, as heard with Keith Jarrett and Gary Peacock.) Jack’s fills and both-directions-at-once coordination have been with us all night, and he fits them smoothly into a medium-tempo blues. This is a magic track.

Four blues and a ballad, plain and simple. “In ’n’ Out” and “Takin’ Off” are so lengthy and intense that they dominate my overall impression of the music. But “We’ll Be Together Again”, “The Believer”, and “Isotope”, relatively short and to the point, almost radio-friendly, are as honest and true as the blues explorations. These are accomplished and serious professionals who can shift from “Takin’ Off” to “The Believer” and keep the momentum.

Does anyone know if the track order is the same as the order of performance?

Final notes:

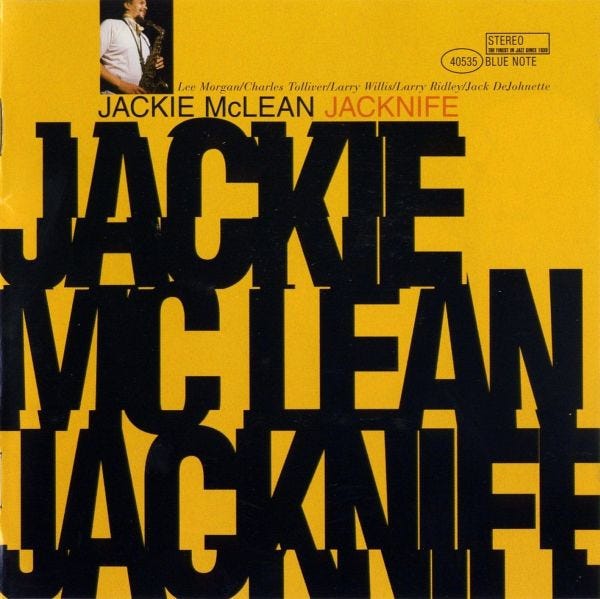

Forces of Nature is some of the earliest Jack DeJohnette we have on record. According to the Lord Discography, the only earlier session is Jackie McLean’s Jacknife from September ‘65 (not released until 1975), with Jack’s modal composition “Climax” a standout.

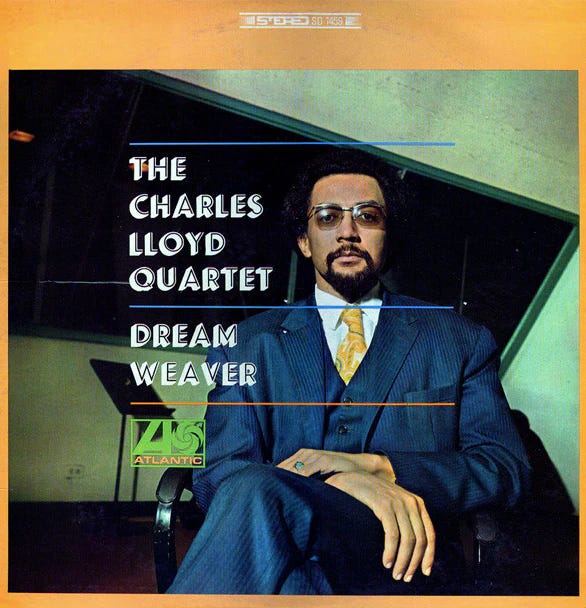

The next album Lord lists for Jack is Charles Lloyd’s Dream Weaver, featuring Keith Jarrett and Cecil McBee, recorded March 1966.

DeJohnette may have been introduced to the listening public on DreamWeaver. In fact, it’s instructive to compare Lloyd’s album to Forces of Nature : both are made in the same calendar year, with the same instrumentation, and both feature Jack DeJohnette.

Dream Weaver is good; Keith and Jack stir it up on “Autumn Leaves”, “Dervish Dance” feels like the prototype for many ECM events, and “Sombrero Sam” is echt-Sixties grooviness. It launched Lloyd’s career, and put him on the path to his million-selling worldwide hit, 1967’s Forest Flower on Atlantic.

But you’d never mistake Dream Weaver or Forest Flower for the strong, uncompromising, and brave music made by McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, Henry Grimes, and Jack DeJohnette at Slugs’ in 1966. By checking in on Lloyd’s Sixties work, we can hear McCoy Tyner and Joe Henderson as the uncompromising virtuosos and folkloric masters they are.

Thinking all this through, I heard Forces of Nature with some deeper gratitude this week, more aware of the real sacrifices and difficulties that McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, Henry Grimes, and Jack DeJohnette stared down to play like that. This was their lives, and they gave us this music. All respect, endless gratitude.

And one more time, thank God for the folks in the club, the devoted listeners who braved the trek to Slugs’ and made it what it was. Like the musicians, these folks kept the legend of jazz at Slugs’ Saloon alive and well. Gratitude and respect.

Going out to play and listen this week, with McCoy Tyner and Joe Henderson in my head, I started to really feel the connection, to viscerally understand that by keeping the fire burning, McCoy, Joe, Grimes, and Jack made our world of music possible. 1966 to 2024 isn’t that much time. It’s all still going.

Looking ahead to 2025, I’m more sure than ever of the core message of this Substack— there is truth and beauty in front of us at all times, if we look and listen. The musicians show us how to turn straw into gold. If Slugs’ was a dump, listen to Forces of Nature and feel the truth of Richard Davis’s words: a dump can be a paradise.

DeJohnette’s birthday is August 9, 1942, so depending on when Forces of Nature actually occurred— we only know it was 1966— he might have been 24. Looking at Charles Lloyd’s discography and known concert dates— Lloyd was getting busy throughout 1966— I bet Forces of Nature was recorded before Jack’s 24th birthday. Of course, this is little more than a hunch.

Been waiting for some sustained critical engagement with this album, and I appreciate yours, Vinnie! To answer your one Q: no, the sequence on the album does not precisely reflect the set list. I don't know precisely what the original order was, but I can attest that Jack was an active producer of this reissue, and had some say as to how the album flows.

DeJohnette was hired by Coltrane to play in his band in March of that year in Chicago.

Coltrane & Co.

at The Plugged Nickel

John Coltrane – tenor & soprano

Pharoah Sanders – tenor & flute

Alice Coltrane – piano

Jimmy Garrison – bass

Jack DeJohnette – drums

Rashid Ali – drums

March 2-6, 1966

Coltrane’s week here confirmed ASCENSION, made it clear that John intends to extend himself into a spasm of “mystic” experience. Which explains the music, and why he is digging into soul and pock to enlist the young lions, aligning their powers with his.

Wednesday night sounded as though giant hands were breaking open the earth, great sounds and chunks of things coming loose. John was blowing against a wall which tottered but wouldn’t fall, then backing off into the stomach-lurching rollercoaster of his more familiar style. Two drummers are pertinent to the music, functioning in a way comparable to a guitar team; while DeJohnette played “rhythm”, Rashid wove “melody”, a steady pattern of rhythmic filigree similar to the flying carpet Ed Blackwell spreads. But the most urgent voice of the night was Pharoah Sanders, toes plugged into some personal wall-socket, screaming squealing honking, exploding echoes of encouragement among the audience. Pharoah was a mad wind screeching through the root-cellars of Hell.

Friday night. How do you review a cataclysm? evaluate an earthquake? An apocalyptic juggernaut that rolled across an allusion to My Favorite Things into a soundtrack from an old Sabu movie – jungle-fire, animals rampaging in panic, trumpeting of bull elephants? You can only describe with impressions saved from the storm. DeJohnette walking away blanched and shaken from the demands of the music. Mrs. Coltrane sitting sedately by, occasionally edging in with comment. Garrison plugging away, helping hold things together. Pharoah a mongoose shaking a snake. Roscoe Mitchell, sitting in on alto for the night, breaking loose with lashes of short-range lightning, some of the most exciting playing to come out of the mass. Saxophonists reaching for tambourine, claves, beaters, etc. whenever resting the horn. Rashid coming through undaunted near the end with a fresh new drum-dance. A locomotive of horns, Pharoah-Trane-Roscoe in a row blowing at once, spinning wheels, throwing cinders. Roscoe becoming “possessed” with revival-frenzy. And the big punch of Coltrane, somehow keeping his head in the melee, breaking through time after time with groaning lyricism. Like a convulsion they had induced but no longer seemed able to control, it ground on and on, beyond expected limits of endurance, past two hours, past closing time, until the management intervened and closed it down.

The audience filed out into the morning, stunned and bludgeoned. The comfortable had been disturbed. The merely hip had been driven back to protests of cacophony, anarchy, disorder. And even the most open ears had become numbed by the continual barrage – one of the problems of the music. What do you carry away from an avalanche besides awe? Another problem – the piano solos and Garrison’s long masterful bass solos remain interludes, adjuncts unaccepted by the bulk of the music. But there were elements of order at work even if we were eventually deadened to them. A peripheral order that contained the inner disorder (pigs fighting in a gunny-sack, the sack enclosing their thrashings). Order from the momentum of the rhythm which pulled things along with it. Maybe a second bassist, say Donald Garrett, would have added that much more. And order from the herding sweep of John’s tenor.

Even at its best, the music never achieved the free flow of Ornette (the comings together and conversation of Free Jazz), or the arranged blossoms of sound-clusters of Sun Ra, or the paradox of complete control/freedom clarity of Albert Ayler (those open ringing bronze Bells, vibrating to their own self-shaping song and logic), but it does have excitement and immense raw power – an experience in itself. What they did prove was just how hard they could try. That they could beat themselves bloody pounding at the farthest reaches of experience and come back with only their effort as an answer. Perhaps that alone is their answer.

-- J.B. Figi

Chicago