Night Train

Shuffles, boogie-woogie, and blues always take us back to the future

Leon Ndugu Chancler plays a subtle, expressive, and immediately ear-catching version of the first drumset beat everyone learns on Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean”. In the Seventies, Chancler toured with Miles Davis and recorded with Herbie Hancock, Santana, and Weather Report, but it’s Jackson’s “Billie Jean”, from 1982, for which he’s best known.

The first two bars of “Billie Jean” is Chancler unaccompanied, timeless dance music on the bare essentials of the drumset— bass drum, snare drum, and cymbals (a closed hi-hat). With his right hand on the hi-hat, Chancler plays eighth-notes; with his right foot, the bass drum on beats 1 and 3; with his left hand, the snare drum on 2 and 4. That’s Lesson One on the drumset, and Chancler’s whispering hi-hat with strutting bass and snare guide us to the heart of Jackson’s still-mysterious smash hit.

Chancler’s all-time rendering of Drumset Lesson One is a distillation of centuries of African-derived wisdom. Originally, Drumset Lesson One was a shuffle, which we get by swinging Chancler’s even eighths. Here’s Jo Jones playing his version1, on hi-hat and snare.

It sounds easy, but it’s just about the hardest thing. A shuffle is physically and mentally draining— you’re playing endless eighth notes, and if one of them is out of alignment, it throws off the whole thing like a flat tire— the music will sputter to a halt. The essence of modern jazz performance might be “make hard things look easy”, and nowhere is that illustrated better than the shuffle.

The shuffle is exactly half-way between the Kenny Clarke/Max Roach ride cymbal paradigm and the modern backbeat. As drummer and educator Daniel Glass has long demonstrated, if you put a backbeat on a shuffle and straighten those eighth notes, voila, the modern rhythmic world emerges. Thanks Daniel!

In the 1910s, pianists in the American Southwest were playing up-tempo twelve-bar blues in a powerful two-handed style, the right hand singing out riffs and dance calls while the left hand2 bouncing out astonishingly swinging eighth notes. Known by a confusing panoply of names, including “fast western”, we know it best as boogie-woogie. On the piano, the drumset’s shuffle is a boogie-woogie.

Get a shuffle and boogie-woogie together— a piano and drumset— and you’re cooking. Add a blues singer to this, and you’re really cooking. Sooner or later, we’re going to get trains3: going to Chicago, sorry that I can’t take you; train I ride is sixteen coaches long; choo-choo-ch-boogie.

“Night Train” sums up the whole scene. Missing a blues singer but graced with a simple and poetic title, emblematic of tenor sax-based R&B/rock and roll, “Night Train” brings together all the ideas and practices that go with this sound— social dance, boogie-woogie, blues melodies, shuffles, and trains.

The song itself has a fittingly winding lineage. “Night Train” is credited to tenor saxophonist Jimmy Forrest, who launched the tune with his hit version in 19514 . Forrest’s original, strictly instrumental and quite slow, with stop time and prominent hand percussion, is great: clear, direct, evocative, and sexy. No wonder it was a hit.

The complete melody of “Night Train” stretches over three choruses of 12-bar blues. Each chorus has its own character, and each leads perfectly to the next. If you’re gonna play “Night Train”, you have to play the whole thing: cut even one chorus out and you got nothing. It’s a blues, it’s a hit, and it’s a composition.

Sound familiar? No surprise then that “Night Train” has long been said to have a connection to Duke Ellington5. A quick Wiki search says that “[Night Train]’s opening riff was first recorded in 1940 by a small group led by Duke Ellington sideman Johnny Hodges, under the title “That’s the Blues, Old Man”. Hmm.

“That’s The Blues, Old Man” was issued on Bluebird, one of RCA’s many budget labels, and in 1940, RCA was Ellington’s home6. Plus, Hodges was much more than an “Ellington sideman”— he was Ellington’s star soloist, such an integral part of Duke’s sound that he and Ellington are forever linked.

According to the Lord Discography, “That’s The Blues, Old Man” was recorded in Chicago, November 2, 1940, credited to Johnny Hodges and Orchestra, with Hodges and Irving Mills listed as composer. So far so good, but go to discogs.com to view a picture of the 78 itself, and you’ll see the phrase “An Ellington Unit” on the record label.

That “Ellington Unit” turns out to be an Olympian summit of Ellington Orchestra principals— Hodges, but also Cootie Williams, Lawrence Brown, and Harry Carney in the front line, with Sonny Greer, Jimmy Blanton, and the Maestro himself on piano.

After an 8-bar introduction, we hear an early version of what we know as the first chorus of “Night Train”. One listen and it’s clear: “That’s The Blues, Old Man” is an Ellington piece. Perhaps they were Hodges’s notes, but it’s an Ellington arrangement played by the Ellington band, with Duke himself present.

Like all Ellington music, “That’s The Blues Old Man” is meant to set a mood, call up images, tell a story: Hodges rhapsodizes on soprano, Cootie Williams talks and sings with the plunger, Greer rolls on the cymbals, and Ellington comments and summarizes. This is the ‘Ellington effect’, the thing that set Duke and his orchestra apart from the very beginning.

Certainly, Jimmy Forrest, who played with Ellington in 1949 and 1950, was aware of all this.

The origins of the rest of “Night Train” are also clearly Ellington-derived. The second and third choruses7 are from Duke’s “Happy Go Lucky Local”, a movement of his Deep South Suite, first recorded in concert on November 10th, 1946 at the Civic Opera House in Chicago8.

Really, the story is simple:

“That’s The Blues Old Man” (1940) contains the germ of the melody of the first chorus of “Night Train”;

Two moments in the middle of “Happy-Go-Lucky-Local” (1946) gave us the second and (roughly) third chorus. Put these together and re-arrange as necessary to get:

Jimmy Forrest’s “Night Train”, 1951.

So the conventional wisdom is true: “Night Train” emanates from the Ellington organization and, in a sense, is an Ellington tune.

However, “Night Train” is also a Jimmy Forrest composition. Neither of Duke’s pieces matches “Night Train” note-for-note, nor was Duke going for wide appeal like Forrest’s canny and effective “Ellington for the kids”. For fairness’ sake, Duke’s or Hodges’s name should be next to Jimmy Forrest’s, but that’s another story.

I don’t know of Ellington ever making a formal legal claim for authorship of “Night Train”, and I certainly can’t imagine the man, Duke Ellington, center of the universe, giving one hoot about a hit record that borrowed from his ideas9. We all live in Duke’s universe anyway— what’s one more or less hit record?

Maybe Jimmy Forrest would have agreed. Listen to his “Night Train”, and we know he understood Ellington perfectly, using Ellington material and techniques to craft a timeless R&B hit. No wonder “Night Train” has lasted— Jimmy Forrest knew exactly what he, Ellington, and Hodges were doing.

“Night Train” immediately became an R&B standard, so emblematic of the genre that James Brown, who added lyrics, straightened out the ternary shuffle into an undulating binary, and had his own hit with it, used the tune to close his stage show— it appears on his original Live At The Apollo from 1962 and on his segment of the T.A.M.I Show in 1964; the Brown scholars out there can let me know if and when it vanished from his live show.

Of course, my cohort learned “Night Train” from Back To The Future. Time moves differently now— “Night Train” was a sprightly 34 years old in 1985, yet Robert Zemeckis’s movie depicts the song, the band, and the dance as ancient history, while Back To The Future: The Musical played on Broadway into this calendar year, 40 years after the movie’s release.

I don’t like dinging an accomplished film composer and fellow working musician, but I can’t imagine that any of Alan Silvestri’s derivative and anxious songs for Back To The Future: The Musical will live in the hearts and minds of music lovers alongside the three blues choruses Hodges and Duke gave us eighty years ago.

But why concern ourselves with splashy, money-spinning Broadway musicals when we have a drumset, the American invention that set the world on its ear? The drumset gave us the shuffle, which enabled the train-traveling big bands to play the boogie-woogie, previously the sole property of pianists. It was in this setting that the backbeat, the defining feature of modern pop music, was first heard10. The whole story is there in “That’s The Blues, Old Man”, “Happy Go Lucky Local”, and “Night Train”. Thank you Duke Ellington, Johnny Hodges, and Jimmy Forrest.

Musical time is more a circle than a line. Back to the future indeed.

“You Need To Rock”, the closing track on Side By Side (Verve, 1959), Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges. On “You Need To Rock”, that’s Billy Strayhorn, not Ellington, on piano, plus Jo Jones, bassist Wendell Marshall of Count Basie, and a front line of Ben Webster, Roy Eldridge, Lawrence Brown, and Johnny Hodges. I read that line-up and think about their lives, and what else can I say but “WOW!”?

A shuffle on the drumset and boogie-woogie on piano is roughly equivalent to a 100-yard dash where the winner must have the shortest time and exert no visible effort.

The emergence of boogie-woogie piano is quite complex and best left to full-time scholars, but I can report that some think that the “western” in “fast western” is a reference to a Texas train line, and Robert Palmer’s Deep Blues includes descriptions of Texas lumber camps with piano entertainment. What’s clear is that the world that gave us boogie-woogie is long vanished, while the boogie-woogie remains.

Recorded in Chicago and released on United/Delmark.

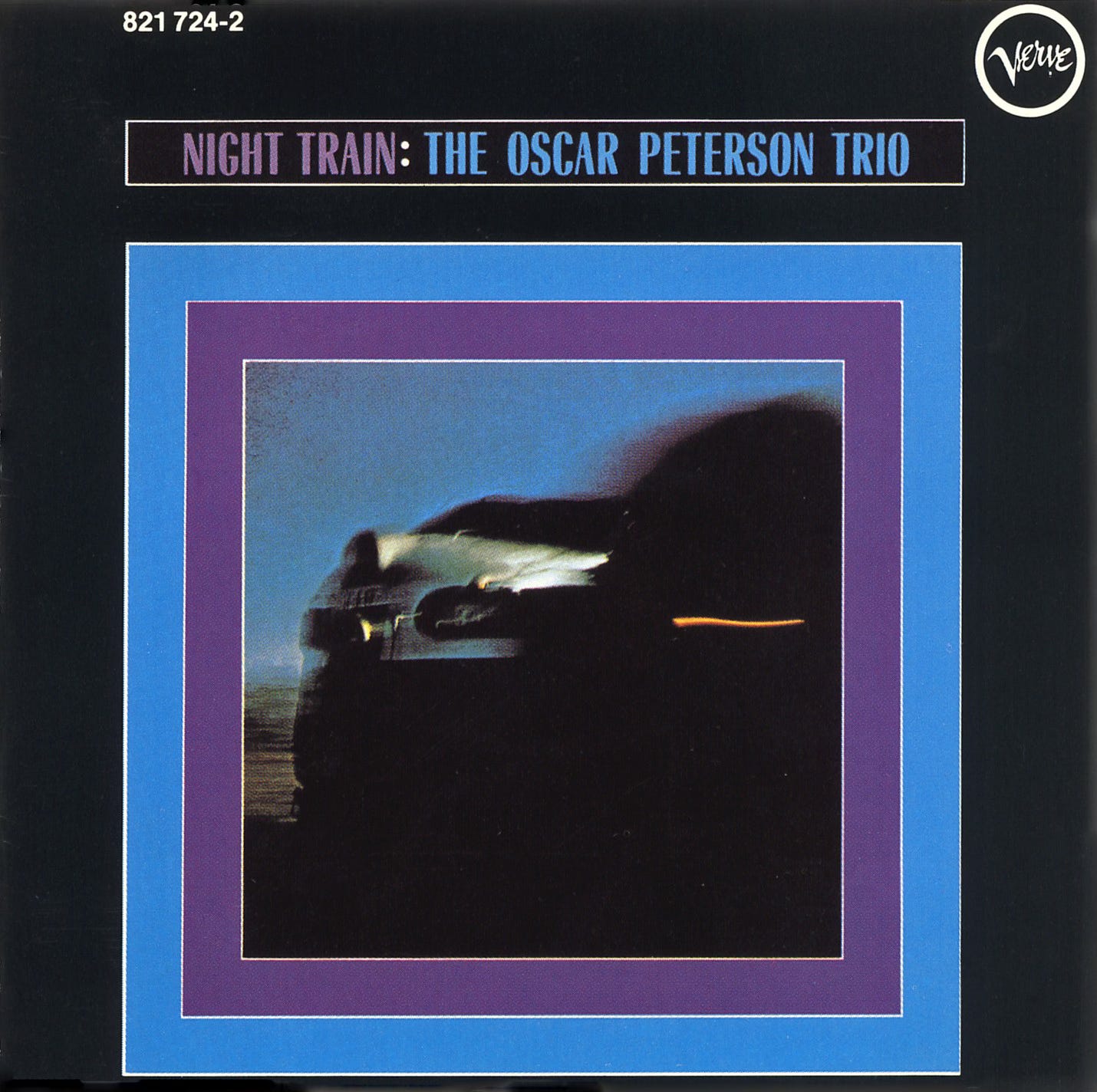

In fact, when I bought Oscar Peterson’s Night Train on compact disc in the Nineties, the liner notes went so far as to re-title “Night Train” as “Happy-Go-Lucky-Local” and credit it Duke Ellington.

Ellington’s RCA releases in 1940 were perhaps the apex of Ellington’s artistry and popularity. My cohort knows them as part of The Blanton-Webster Era, the title of various CD and streaming collections.

The second chorus melody is the shuffle/boogie-woogie bit, where the saxophone plays two bars of eighth notes, the aural depiction of a train chugging down the tracks. The third chorus has the rhythm section play beat one while the melody spirals into triplets and blues.

On this gig, the Maestro’s orchestra is joined by Oscar Pettiford, no less. The Blanton/Pettiford connection is now clear as day. Also this concert is smoking. It should be widely known and loved, it’s so great.

Duke recorded a smoking version of “Happy-Go-Lucky-Local” for Columbia in 1961, by which time “Night Train” was an established standard. The liner notes by producer Irving Townshend doesn’t have a word about “Night Train”, and simply notes that “Happy Go Lucky Local” “is the famous section of Duke’s Deep South Suite which describes a Southern train”.

Heard outside the Black baptist church, that is. The ‘gospel handclap’— the congregation clapping on 2 and 4 while singing, practiced in Black churches— is the precursor to the backbeat.

as far as we know, this is the first recorded boogie woogie, from 1924, by an early and great Chicago pianist (Chicago Stomp by Jimmy Blythe): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LtFfLwcrlZc

Incredible history

I have successfully avoided listening to Oscar Peterson my whole life, but I'll check out 'Night Train'

Thanks, Vinnie!