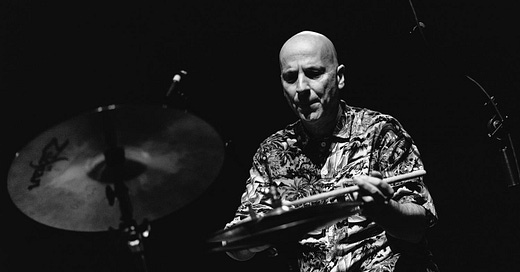

Joey Baron is a treasure, a fount of wisdom and experience, a restless, uncompromising inventor with the highest musical standards. I last saw him in New York at Birdland in the summer of 2022, playing with Marc Copland, Randy Brecker, Billy Drewes, and Drew Gress, a beautiful night of music.

Throughout the set, Joey swung and smiled, subtly shading the music by coaxing countless tiny gradations of tone from his cymbals and drums. He was deeply inside the tunes, spurring the soloists, blending with the band, generating heat, cooling it down, an individual and a team player. It was a joy to behold.

On the surface, that night at Birdland might seem a far cry from the avant-garde milieu of John Zorn, Tim Berne, and Bill Frisell that brought Joey Baron to the ears of listeners in the Eighties. But beneath the surface, Joey Baron is moving forward and suggesting possibilities, as he’s done his whole career.

This is what makes Joey Baron special:

Joey Baron brings his command of just about every musical style heard in North America to every gig he does. Jazz, rock, and soul/funk/R&B of course, but he keeps going. Even with a relatively straight-ahead piano trio, Joey might reference gospel, blues, or country music. He has a deep awareness of Afro-Cuban and Afro-Caribbean traditions1, and might, depending on his mood, nod towards radical versions of rock music— punk, metal, grindcore— or something from the celebration music of the Jewish diaspora. And there is a reverence for the full spectrum of American commercial music— jingles, TV theme songs, soundtracks, TV orchestras, and so on.

I could hear all this, in flashes and implications, that night at Birdland with Marc Copland. But that’s simply Joey’s voice. He’s sublimated his influences and skill into a seamless, instantly identifiable sound; this might be the highest level of mastery.

For instance, I remember him playing “Wipe Out” with his band Killer Joey at Tonic, ca. 2000. At first, I couldn’t believe the great Joey Baron was playing “Wipe Out”; seconds later, I was wondering why I didn’t have a band to play “Wipe Out”, because Joey and his band made “Wipe Out” sound amazing2. His musicianship and generous spirit had completely convinced me.

Finally, Joey Baron is as big an influence as there’s ever been. Based on my non-scientific method of talking to every drummer I know about drummers, all the time, Joey Baron’s name always comes up. Just off the top of my head, Ben Perowsky, Josh Dion, Jim Black, and Mark Guiliana have all talked about his influence.

Here’s Dave King:

“I’m usually able to keep my shit together, but to this day, when I run into Joey Baron, it’s difficult for me to not remind him of the impact [of seeing him play in the late 80’s]…seeing Joey Baron at that time was very eye-opening.” 3

To me, the swing thing was the real challenge. How could these guys play four quarter notes and get it to feel so full? So it was my goal to really investigate that, and I got the hands-on view of it from working with Carmen [McRae]4. -Joey Baron

Joey started his career in Los Angeles, playing with Blue Mitchell, Art Pepper, Hampton Hawes, and, most notably, Carmen McRae. Carmen McRae at the Great American Music Hall (Blue Note, 1977), featuring Dizzy Gillespie, is the first easily-available release with Joey Baron on drums.5

It’s an incredible album. McCrae is on fire, the band is great, and the repertoire is a mix of heavy 4/4 swing, ballads, backbeats, a samba. Baron and McRae share a seriously swinging eight-bar duet on “Too Close For Comfort”, while the very slow (less than 40 beats per minute) version of Bill Withers “Paint Your Pretty Picture” is a masterclass in timekeeping.

For me, “On A Clear Day” is the special track. After Ms. McRae sings a chorus, we get a Dizzy Gillespie solo. On beat 4 in the fifth bar of Dizzy’s bridge, Joey smacks a crash cymbal and a snare drum, a great choice in the moment— loud, brave, ear-catching, charismatic, and slightly irreverent. From our vantage point, it’s a telltale sign, a foreshadowing of much Joey to come. Whenever I hear it, I immediately think “Ah ha! I know who this drummer is!”

Listening to Joey with Carmen McRae helped me understand that Baron wasn’t destined to play with Frisell, Zorn, etc. Indeed, when he recorded Carmen McRae At The Great American Music Hall, he had yet to even meet them. Rather than fate at work, Joey chose to play with the NYC avant-garde community. Joey’s career was no miracle, no accident— he worked hard, made some tough choices, and became the player and force in music we know.

“I spent 7 years out there [in LA] and that’s when it started to hit me that something was wrong…I needed more of an outlet than just working other people’s gigs functionally. I liked doing that for the first few years, but later I was trying to do something else, and I didn’t know what….So I started to feel that maybe I should leave LA and come to New York.”6 - Joey Baron

When Baron arrived in NYC, his first order of business was to make a living, so it was “club dates, strictly club dates7”, but soon was doing gigs with Toots Thielemans and Jim Hall, and making records with Jimmy Rowles, Fred Hersch, Gary Dial and Dick Oatts, Roseanna Vitro, and Herb Robertson.

It was on Herb Robertson’s Transparency (JMT, 1985) that Tim Berne, Bill Frisell, and Joey Baron first recorded together. Not one track from Transparency is streaming on any platform as of January 20238.

“What you’re hearing is rooted in ordinary things- that’s where I start. I made up my mind that I would take what I love about traditional jazz and add to it. I went from being someone who had a rep as a tasty accompanist to someone who people thought couldn’t play a bar of of straight time!” -Joey Baron9

In March 1987 (the same year that Ralph Peterson began recording for Blue Note with Geri Allen) Bill Frisell, Hank Roberts, Kermit Driscoll, and Joey Baron entered the Power Station in NYC to make Lookout For Hope (ECM, 1988).

This was the first in a series of four albums recorded in a 12-month period (March ‘87- March ‘88) which feature a similar personnel. Together, they give us a snapshot of Joey Baron as he transitions from a “tasty accompanist” into the musician and spirit we know and love today. The change was ultimately more conceptual than technical: now Joey just allows every influence to manifest, as it happens, in the flow of the music.

The four albums are:

Bill Frisell: Lookout For Hope (ECM)

Bill Frisell/Hank Roberts/Kermit Driscoll/Joey Baron. Recorded March 1987, Power Station, NYC.

Tim Berne: Sanctified Dreams (Columbia)

Tim Berne/Herb Robertson/Hank Roberts/Mark Dresser/Joey Baron. Recorded October 13-15, 1987, Power Station, NYC.

Hank Roberts: Black Pastels (JMT)

Hank Roberts/Tim Berne/Ray Anderson/Robin Eubanks/Dave Taylor/Bill Frisell/Mark Dresser/Joey Baron. Recorded and mixed November/December 1987, RPM Sound Studios, NYC.

Miniature: Miniature (JMT)

Tim Berne/Hank Roberts/Joey Baron. Recorded March 1988, RPM Sound Studios, NYC.

For Baron, suddenly, all options were on the table. His radical openness was not for the sake of novelty, or easy effects. Joey Baron allowed the whole range of musical styles to be present to make the music sound good. This community of players— Frisell, Berne, Roberts, Robertson, and others— all did this in their own way.

Respect and gratitude.

Joey was not alone in bringing the new collage-style sound to the drums— Phil Haynes, Alex Cline, Anton Fier, Bobby Previte, and others were making contributions as well. In the future I’ll explore their music.

In the meantime, I really love these albums; this is powerful music. Let’s take a brief listen.

In Philip Watson’s invaluable new biography of Frisell, Bill Frisell: Beautiful Dreamer (Faber and Faber, 2022) he suggests that Lookout For Hope is a landmark in Frisell's discography, a meaningful statement of intent. Without a doubt, the Frisell sound is in full bloom here, and so is Joey Baron.

As great as Joey always sounded, he simply wasn’t playing like this with Carmen McRae, Fred Hersch, or Red Rodney.

On the 12/8 title track, Joey is powerful and explosive, almost a co-soloist with Bill. But he never overwhelms; this is just the chemistry of the band. “Lonesome”, a classic Frisell melody, has Joey playing a lovely straight-ahead country beat with brushes, but the spontaneous and mood-changing cowbell and woodblock connect the track to the avant-garde.

“Alien Prints” closes the album with some joyous, virtuosic rock/R&B drumming for Frisell’s solo, while Hank Roberts plays like like a rhythm guitar and Kermit Driscoll keeps it all connected; Joey’s 7-second flam fill at 3:51 is OMG… The energy recedes, and they ride off into the sunset.

Tim Berne’s Sanctified Dreams (Columbia, 1988) was his second and last Columbia Records release, the follow up to his critically acclaimed Fulton Street Maul (CBS, 1987). Recorded just a few months after Lookout For Hope, Sanctified Dreams demonstrates how quickly Joey was expanding.

With Bill Frisell, Joey could play idiomatic rock and jazz, through his own filter of course. But Tim Berne’s music is much less idiomatic than Frisell’s, with fewer direct references to rock, jazz, R&B, and so on. No problem— Joey uses his musicianship and artistry, supports Tim’s compositions, and lets his voice come shining through.

“Velcho Man” features Joey setting up Tim’s melodies with the wisdom and grace of Mel Lewis, navigating an elaborate, fully-realized arrangement as easily and lightly as if it were a collective improvisation. On “Elastic Lad”, Joey seamlessly transforms an improvised duet with Hank Roberts into a rocking 6/8 for a full-band reading of Tim’s theme. “Terre Haute” (Hank Roberts’ hometown) starts with an unforgettable four bars of Joey in funky 5/4, then transforms into a ruminative, African-influenced voice and drum duet.

Recorded at the end of 1987, Hank Roberts’ Black Pastels (JMT) features Bill Frisell, and Tim Berne, and three trombonists. All the tunes are by Roberts, and no track follows a predictable course. An inviting, wholly unique set of music, connecting the avant-garde energy of Tim Berne and Bill Frisell to cutting-edge pop music10, Black Pastels is a perspicuous classic, and shows how diverse and wide-ranging the cohort of Baron, Berne, Frisell, Roberts etc truly are.

The opening title track, played by a trio of Roberts, Frisell, and Joey, features a slow, dramatic buildup centered around Roberts’ wordless vocals, Joey rocking and filling, alternating between two distinct feels, and setting up a classic Frisell solo. Genre distinctions simply don’t matter; when Joey enters on Hank’s lovely “Jamil”, he seems to be almost singing along with Roberts, so connected to the song is he.

Baron plays a quasi-calypso on “Choqueno”, featuring Frisell on a 12-string. Soon they’re joined by a trombone choir for a melody that suggests gospel, Eddie Palmieri, and Eighties pop. I can’t think of another track like this anywhere in jazz, sort of the intersection of AACM experimentalism and David Bowie. Stunning.

On “Lucky’s Lament”, the album closer, Hank, Frisell, and Mark Dresser keep the funeral march feel as Joey shakes his shakers and rattles his toms, while Tim gives his blues and R&B side a chance to shine.

In the midst of all this, Tim Berne had organized a trio of himself, Joey, and Hank Roberts, called Miniature. The group was a collective, so everyone brought in tunes, though Hank Roberts told me repeatedly, regarding Miniature, “So much came from Tim; he made so much happen”. Miniature has a distinct personality, a lot of humor and many references to current pop music. Their two records stand out in Tim’s vast discography11.

Their sense of fun and play comes through on their first album, Miniature (JMT, 1988). This is the debut of Joey’s ‘electronic’ set, where his 4-piece Sonor kit is outfitted with MIDI triggers and augmented with a Casio CZ-101 keyboard. The liner notes state that there were no overdubs, so everything we hear is live.

Roberts’ “Ethiopian Boxer” suggests R&B and the new ‘world’ music sound; Joey uses his bare hands on MIDI-triggered drums and generates density with the keyboard.

Berne’s “Circular Prairie Song (For Bill Frisell)” a through-composed three-part suite in two and a half minutes, features some whoopee-cushion sounds on Joey’s keyboard and Hank’s spoken outro. Yes, I actually LOL, every time I hear this track.

“Lonely Mood”, a serious and effective piece Baron composition, features a moment of stark beauty when the alto and cello unison is broken with an entrance from Hank’s voice, all while Joey creates a forest floor of texture with keyboard, cymbals, and MIDI drums.

Berne’s “Narlin” features Joey playing a second-line groove, a bluesy alto melody, and a moment of Hank Roberts gospel cello (at 4:20) that makes me want to cheer. Hank’s “Abeetah” abruptly switches from quasi-punk to slow swing with the funniest keyboard solo (played by Joey) I’ve ever heard.

Tim Berne’s “Sanctuary” features a motivic Baron drum solo12 and concludes with a tough, beautiful melody, masterfully orchestrated and swung by Joey, bringing us to the close of an astonishing 12-month run of recording.

So much was happening; trying to summarize or provide an overview of Joey Baron’s activity at this time is daunting. Just listing other important records Joey made with many of the same players in the same era, we could include John Zorn’s Spy vs Spy (Elektra, recorded 1988) and Naked City (Elektra 1989), Frisell’s Before We Were Born (Elektra, 1988) Is That You? (Elektra, 1989), Where In The World (1990), and Live (recorded 1991, released 1995), Tim Berne’s Fractured Fairy Tales (JMT 1989), I Can’t Put My Finger On It (JMT, 1991), David Sanborn’s Another Hand (Elektra, 1991), and on and on.

This was one of the sounds of the Eighties, concurrent with the contributions of Wynton Marsalis, Ralph Peterson, etc. Taken altogether, this scene created the context for the great music being made right now.

Joey Baron is with us today, playing, recording, touring, teaching. I’ll be looking for him the next time he’s in NYC, or when I’m next in Europe. His music is unfinished, there’s still so much more to explore. The next time I hear him, I know I’ll hear something I’ve never heard before.

In 1987 and ’88, Joey Baron, drawing on his professional skills and affirming his own agency, connected the new sounds made by his friends Bill Frisell, Hank Roberts, and Tim Berne to what he called “ordinary things”. In so doing, Joey Baron was able to dispense wisdom, communicate joy, and celebrate possibility.

Baron and his comrades inspired countless listeners to hear music a different way— without hierarchies, or boundaries, with room for all.

The experience of music as one phenomena, one practice which can connect all humans, is always possible present when Joey Baron plays.

All respect and gratitude for Joey Baron.

Very special thanks to Hank Roberts and Tim Berne for their time, generous support and help understanding the context of their music in 1987, 1988, and beyond, and to Josh Dion for help with this article.

Joey Baron snapshot: one of my first email exchanges with Mr. Baron, in 2015, was about Bill Fitch, a conguero who recorded with Cal Tjader, about whom Joey had learned from Milford Graves. Joey was at an Albert Tootie Heath clinic at the Drawing Room in Brooklyn, and when I approached him, he told me excitedly about Fitch’s tone, that Fitch was a big influence on the whole NYC Afro-Cuban, and so on.

Possible line-up for Killer Joey that night was Steve Cardenas and Tony Scherr on guitar, Thomas Morgan on bass, and Joey on drums; but I’m not certain.

Dave King, Walker Reader, 2017

Joey Baron to Bill Milkowski, Modern Drummer, March 1989

Thank you to Mr. Steve LaSpina for showing me this album when I was at William Paterson; Steve spoke so highly of Joey, and told me about the Jim Hall album he and Joey played on that also featured Tom Harrell, Jim Hall: These Rooms (Denon 1988). Recorded between Hank Roberts’ Black Pastels and Miniature, it’s a beautiful album, not streaming anywhere as of January 2023.

Joey Baron to Bill Milkowski, Modern Drummer, March 1989

Joey Baron to Bill Milkowski, Modern Drummer, March 1989

When I get a hold of a copy, I’ll write about it right here.

Joey Baron to Ken Micallef, Modern Drummer, July 1996

Case in point: Hank Roberts told me that somewhere in this period, perhaps 1990 or ‘91, he played a Tim Buckley tribute concert produced by Hal Willner (one of the earliest to articulate a version of the sensibility of this music) where Hank played in a group with Tim’s son, Mr. Jeff Buckley. Jeff Buckley, according to Hank, was very aware of Hank, Bill, etc., and he and Hank hit it off, talked about playing more. Hank was invited to play on the album that became Grace, but it didn’t pan out (Hank thought it must have been a schedule issue). Hank’s high, wordless falsetto, Jeff Buckley’s high wordless falsetto…..

In the same conversation, Hank told me that he didn’t think he’d laughed so hard or so often in his life as he did touring with Miniature and with Tim’s sextet.

At 2:38, I believe Joey uses his foot to raise the pitch while he rolls.

One of my first “name” gigs was subbing for Uri Caine in the Dave Douglas sextet. Joey Baron was the drummer. Of course I idolized Joey (still do) but the day I met him was memorable for another reason. I was kinda into cards (especially poker) at that point and had a deck in my bag. We were in the back of the van, and James Genus told me that Joey did card tricks and magic. Joey shrugged. I reached down and handed Joey MY DECK, saying, “really?” Joey then put on a long insane demonstration of sleight-of-hand -- again, with my deck, so he couldn’t have tampered with it in advance. What a moment!

This is a beautiful tribute to a living master, full of insight, enthusiasm and love. I wish more musicians and writers would do this service for masters like Joey Baron and not wait until they've checked out. Thank you, Vinnie Sperrazza!