Background note: The goal of most of my essays is to direct your attention to corners of music history which are often unnoticed; specifically, the hidden-in-plain sight connections between genres and eras, focussed on drummers. Here, though, I’m writing about something of huge personal significance for me, so a few words explaining myself might be appropriate.

First, I’m going to talk about a time in my life of intense, rapid personal and professional growth; it’s not an exaggeration to say that this was my graduate and doctoral years, compressed into four months. I hope that many of my readers will recognize themselves in my story.

Second, I’m describing the core values and aspirations of my music and writing, which I’d like to think can be applied usefully to any human endeavor. Those values were awakened by the special experience I had in these four months.

Finally, I’m writing about a recently and too-soon departed friend and inspiration, singer Luqman Brown; this essay is for him, in his memory and honor.

Luqman Brown, among many others, was an early encourager of my writing; I only realize now how much a part of me he is.

Stew (one name) is a singer, songwriter, guitarist, playwright, and teacher. He frequently works with Heidi Rodewald, singer, songwriter, bassist, composer, and arranger. With a full complement of drums, keys, and assortment of horns and strings, Stew and Heidi play and record as Stew and The Negro Problem.

Stew’s lyrics and melodies run the gamut from poetic evocations of everyday life, personal confession, jokes and wordplay, social commentary, and a broad, humble, humanitarian spirit; Heidi Rodewald’s music and arrangements have something of the sophisticated psychedelia of Love’s Forever Changes, a bit of Bacharach, and a lot of pop music about which I need to learn more.

Together, Stew and Heidi write songs which will make you laugh, break your heart, and expand your mind. They have a sensibility adjacent to the jazz musicians I’ve been profiling; all styles are welcome, and all music is included.

At first, Stew led a band called The Negro Problem, an LA baroque pop band who released three albums from 1997-2000 (Heidi joins the band on their second album, Joys And Concerns), which gained some notice. Stew then began recording solo albums, all of which featured Heidi Rodewald, and which gained further notice.

By 2004, it seems, the group was Stew and The Negro Problem, and the main focus was on completing an evening-length compendium of semi-autobiographical stories and songs. By 2006, this was the musical called Passing Strange.

Passing Strange is what Stew and Heidi are probably best known for; it was on Broadway in 2008, won the Tony award for Best Book that year, has been in production in several American cities, and Spike Lee made a movie of the Broadway show— Passing Strange: The Movie. 10 minutes into the first time I saw the movie, I should add, I was a Stew and Heidi devotee. Passing Strange is one of my favorite things, and Stew is one of my main inspirations and a huge mentor.

In the future, I’ll write about Stew, Heidi, and the great moments I’ve had playing their music, but that’s a story for another time. For now…..

….in the summer of 2014, while serving as a member of the crew on Spaceship Stew and Heidi, I was beamed down into the small town of Ashland, OR, home of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

Employed by Oregon Shakespeare Festival, the plan was to rehearse and put up Family Album, a new Stew and Heidi musical, a sort of sequel to Passing Strange which addressed themes of family, aging, artistic longevity, and the inevitable compromises which come with longevity. I was to play the part of Charles Andy, a drummer who gradually morphs into a social media mogul and investment banker.

The job was four months long; I had no acting experience, had never lived on the West Coast, and was a fish out of water.

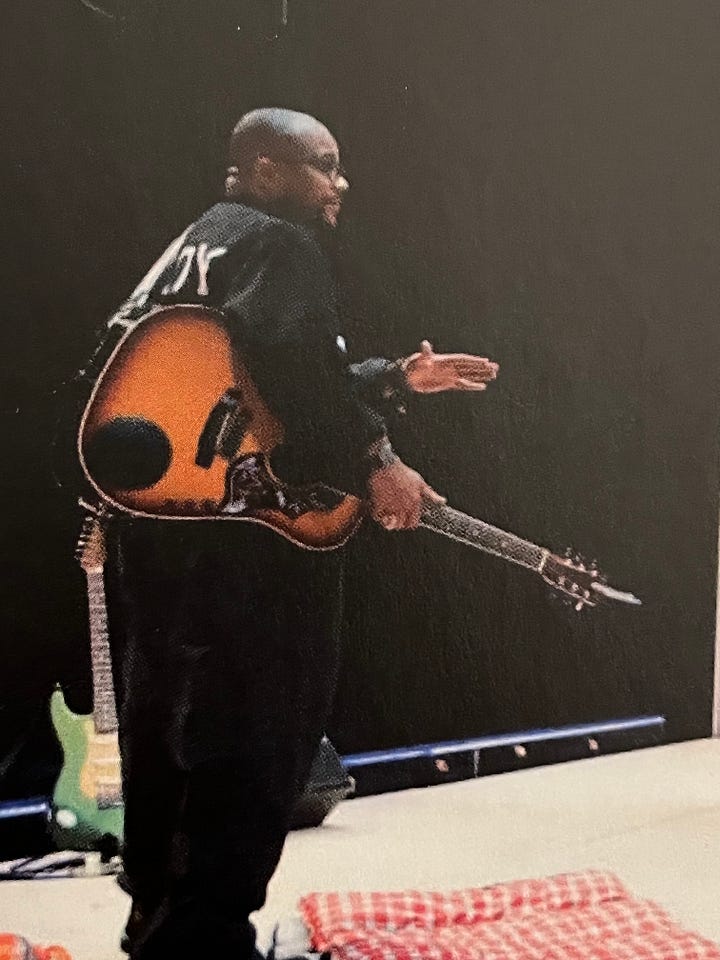

The idea was that the actors would be the band; the musicians would be the actors. In the production were violinist and composer Dana Lyn, cellist Marika Hughes, and guitarist/vocalist Christian Gibbs. On the actor side (they played and sang too) were Casey Scott, Alex Emmanuel, Lawrence Stallings, Daniel Parker, and Miriam Laube, and the male lead was Luqman Brown as singer-songwriter Heimvey1 Swope.

Luqman Brown, then in his early forties, was a part of Greg Tate’s Burnt Sugar, led his own bands Funkface and Dope Sagittarius, was a member of NYC’s musical community since his teenage years; he died on Tuesday, January 10th, 2023.

Here is an interview with him2. Here is a home movie of Burnt Sugar playing some Rick James; Luq is in the hat, on the right. And here is the New York Times review of our show from 2014.

When Family Album rehearsals started, I was completely lost.

Once, when the director, Joanna Settle, gave me a direction, I disagreed with her, in front of the all the actors, a major no-no. Thankfully, I was corrected, and not fired. I didn’t understand the theatre, all the discussions and waiting and testing; I missed New York, and was, for a few days, more or less useless.

Luq, the son of a playwright who’d grown up in theatre, with knowledge of sound design, experience as a touring bandleader and DJ, a powerful, punk-steeped, but smooth singing voice, and a manner which brought out the best in everyone, convinced me to give it my best, and showed me how. Soon, I and the whole band had gravitated to Luq’s work ethic and ease, and I learned a profound lesson in professionalism, kindness, and humanity.

Two or three weeks in, though I knew I would never be nominated for an Oscar, I realized that I loved it. I believed in the work, and loved the people I was working with. Watching the director guide the actors; seeing the level of commitment all the actors exhibited; seeing all the departments interact; and frequently, watching Luqman, nailing his lines, knowing his marks, singing his songs, and giving all of himself— all of this told me that with dedication and sacrifice, I could do more than what I’d done in New York, could maybe be the musician and person I wanted to be.

Plus, I’d never lived without running from one activity to another, typical NYC life. Here, I had the luxury of one activity a day, a rehearsal or a show, with plenty of time to read, listen, write, go to the lake, and so on.

I was never the same. That production, and the way Luqman conducted himself, opened me up for good. I’d never seen such dedication and such high standards, and I patterned myself after him, Stew, and everyone on that show.

One of the Stew/Heidi songs in the show was called “Playing It Safe Is Dangerous”, and it was a commentary on Luq’s character Heimvey’s essentially false representation of himself, how he pretended to be something he wasn’t. Without my realizing it, that title, and the message behind it, permeated my subconscious; when I heard the news of Luq’s passing, it was the first phrase in my head, and I realized it was the lesson I most learned, from the show, from the experience, from Luqman.

Luqman was a musical influence too, helping me listen harder. We shared both a dressing room and a taste for all the great rock bands- Beatles and Zeppelin, but also Genesis, Traffic and Zappa. I remember listening to the original Art Blakey Moanin’ with him, and he said that evoked the Harlem of his childhood better than anything else. Luq showed me George Clinton’s music, beyond the songs everyone knows, and I learned how Clinton was connected to the whole spectrum of Black music, learning about The Parliaments, the barber shop, and so on.

Luq, having grown up around theater, showed me how to talk to all the different workers, how to make friends with everyone, get everyone on the same team. When touring with Ember or with Mark Morris, I still use Luqman’s licks when talking to sound people: “That sounds great! Could we try just one thing?” (He would have said “That shit sounds dope! Can we do just one thing?”).

One day- I think it was backstage- I mentioned to Luq that I’d chased around Paul Motian a lot when he was alive, and that we’d had some funny interactions. I acted out some of them; Paul, brusque but essentially polite, me, an annoying college kid, and Luq laughed and laughed. "That’s some funny shit, Vinnie”, said Luq. “You should write that down, or make a video of it, or something.”

So during one of the slow stretches— we frequently had very light work weeks that summer, sometimes with stretches of three or four days without a show— I wrote it down, working on it for hours at a stretch.

Back in New York, I put the essay on my website, and this little piece of writing,"Five Awkward Conversations With Paul Motian”, brought me into contact with a wider world of musicians than I’d ever known, and was a first step along the road to me writing these essays. The writer I am today is very much a product of Luq’s example and Family Album.

After that summer, we spoke on the phone and saw each other, not often enough. He was never far from my mind; he helped me learn how to appreciate people, how to savor the moment, how to create community, and gather people around you, how could I not be thinking of him? I was sure we would perform together again eventually3.

In a real way, I’m writing in the spirit I saw Luqman Brown exhibit that summer: a generosity rooted in respect for all; nothing dismissed out of hand; understanding that words and actions can shape the world. It took Luqman’s passing for me to realize how foundational our time together was.

No one is an island. When studying music, I always find connections between disparate styles, remote eras, distant genres. Those connections are rooted in personal connections.

I’ve been staring at the screen for hours, trying to sum it up. This is a memoir, but to me it’s the same as the other essays: everything is connected, nothing is cut-off from anything, everything has value. Family Album hasn’t played since that one summer; by conventional measures not a great success. But the cast and playwright are in regular communication, for almost nine years! So what’s the final value of Family Album?

Luqman Brown helped me, he must have helped so many others.

Farewell, deepest thanks, and all respect, Mr. Luqman Brown.

‘heimvey’ is a German word meaning ‘homesick’, more or less.

It lists his nationality as British; Luqman was not British, so either this is some self-reinvention, or an error.

The great saxophonist Avram Fefer knew Luq from Burnt Sugar, and was threatening to get us together. Just another indication of how connected we all are.

Beautiful Vin

This is beautiful and inspiring stuff, Vinnie. Thank you for writing, and my condolences for your loss.