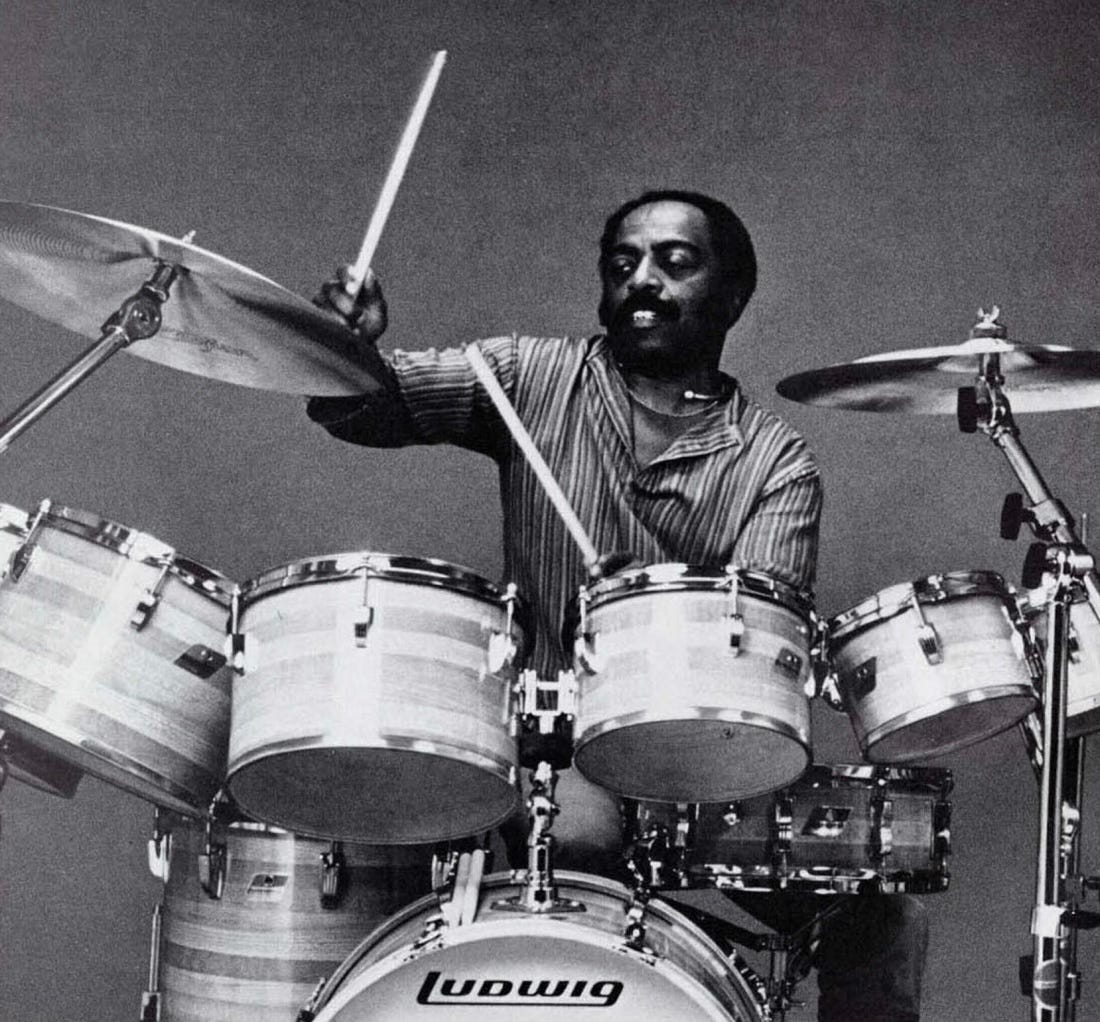

This photo, from a late Seventies ad for Ludwig, was the first thing I thought of when I heard the news: Roy Haynes the indomitable, fearless, and generously stylish.

Roy Haynes, our greatest living jazz drummer, died on Tuesday, November 12th, 2024, at age 99. Coming close on the heels of the death of Lou Donaldson, Quincy Jones, and Benny Golson, we are witnessing an age coming to a close. It’s up to us, to you and me, to keep this going.

These obits, by Nate Chinen for the New York Times and Ben Ratliff for NPR, are heartfelt and informative.

Ethan Iverson’s Substack post has some great comments on Haynes from Billy Hart; another one digs Roy Haynes with John Coltrane.

Ted Gioia wrote a lovely essay contemplating Haynes’s exceptional longevity.

I wrote about three albums Roy Haynes and Richard Davis made together, first with Sarah Vaughan, then with Kenny Burrell, and finally with Andrew Hill.

And this Chick Corea post (with corrections!!!!!) has some words about Roy Haynes and Now He Sings, Now He Sobs.

Roy Haynes doesn’t need commentary or explanation. His music and life speak for themselves. Musicological details will always be secondary to what the music communicates. Anything we say about Haynes’s playing only elucidate the larger point: we love to hear Roy Haynes.

I share my impressions of him to inform, to create a personal connection, and inspire you to listen. All respect.

I put on Chick Corea’s “Matrix” when I heard the news. Haynes’ ageless spirit filled my ears, and his smiling, feinting, now-you-see it-now-you-don’t-wisdom sounded like an embrace of the present, an expression of pure zest for existence. As I listened to “Matrix”, and thought of the times I was lucky enough to hear him play, what screamed across was Roy Haynes’s love of life.

Roy Haynes always sounds delighted— everyone’s here, the music is moving, humor is present, possibilities are endless. That left foot jumping out of a detailed time-keeping pattern, the hi-hat/tomtom unisons in his solos, his clothes and hats, Louis Armstrong, to John Coltrane, to Pat Metheny— this is a way to live. Embrace the moment, meet the challenges.

We’re so lucky to have Roy Haynes. He gave us so much. All respect and endless gratitude.

For Haynes’s 98th birthday, I wrote a post and assembled a Roy Haynes playlist of lesser-known tracks: Roy with Luis Russell in 1946, with Lester Young in 1949, with Jackie McLean in 1964, with Archie Shepp in 1968, and with Alice Coltrane in 1976, among others. I re-wrote the comments, drastically improving the style, but kept the playlist, which I really enjoy. It’s quite a cross-section of Roy’s artistry. I’ve re-posted it below:

Happy Birthday, Roy Haynes

MAR 17, 2023

Roy Haynes is the greatest living jazz drummer. Amen.

The bassist and composer Reuben Radding, in a comment on this Substack, pointed out that some drummers more-or-less reinvented the drumset (Jo Jones, Max Roach, Elvin and Tony), some are dominant influences (Jim Black, Jeff Watts), and some are outliers, important players, widely praised and respected, but whose language was never assimilated into general use— Mr. Radding mentions Billy Mintz and Dave Tough (two drummers about whom I hope to write) as being prime examples.

Roy Haynes is a special case. Mr. Haynes is too important in jazz to be an outlier, but like the outliers, no one has ever sounded like Haynes, then or now. It’s startling to realize that such a pure, complete original as Haynes is the single greatest connector between generations in the entire history of jazz. Roy Haynes, of course, is the through line from Louis Armstrong to Pat Metheny.

While no one’s ever really sounded like Roy, his influence is huge— on Chick Corea’s Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, for instance, Haynes’s playing will always exemplify, always signify “cutting-edge, ultra-modern, badass jazz”, because every current jazz drummer stole something from Haynes. In fact, Jack DeJohnette was already calling Roy Haynes ‘Papa Daddy’ in 1968 (that’s Roy on drums and Jack on melodica).

It’s always a good time to check back in with Mr. Haynes’ recorded work, especially with his 98th birthday on March 13th. In a discography as extensive as his— the Lord discography lists 417 sessions— there’s always going to be something new to hear.

I assembled a highlight reel that explicitly avoids the obvious highlights— Haynes with Monk, with Chick Corea, with Coltrane, later recordings with Pat Metheny and Danilo Perez. Great stuff of course, but I wanted to widen the lens, expand the scope, dig a little deeper.

Here’s a sampling of some lesser-heard Haynes in a YouTube playlist. You can also click on individual tracks below.

Luis Russell Orchestra: “Deep Six Blues”, recorded October 1946, released on Apollo Records. In 1945, after nearly a decade as Louis Armstrong’s musical director, pianist-arranger Luis Russell formed a new band for an extended booking at the Savoy Ballroom. In need of a drummer, he sent a one-way train ticket to the 20 year-old Boston phenom named Roy Haynes he kept hearing about. On the slow, melancholy “Deep Six Blues”, Roy kicks the band, and even sets up a few moments of double time. Though there’s not much room for Haynes to leave his fingerprints on this track, when we hear the snare and bass, we know who’s playing.

Harry Belafonte with Zoot Sims Quintet: “The Night Has A Thousand Eyes”, recorded 1949, released on Jubilee Records. Belafonte, at the beginning of his career, is joined by young turks Sims, pianist Al Haig, guitarist Jimmy Raney, bassist Tommy Potter, and Haynes, who was beginning to travel the byways of modern jazz in New York. Roy commits to the light, rumba-esque beat with panache.

Lester Young: “Sunday”, radio broadcast from the Royal Roost, probably April 1949. Almost a Bud Powell/Max Roach tempo, Prez burns and Haynes lights it up for three thrilling choruses. After trumpet (Jesse Drakes), trombone (Ted Kelly), and piano (Junior Mance), we get two stunning choruses of fours between Lester and Roy, glory be. Roy had just turned 24, and he sounds exactly like himself— precise, almost even-eighth note on a high-pitched cymbal, with a high, tight snare drum and a low, thuddy bass drum in constant communion with the soloist. Special thank you to Loren Schoenberg for making this music available.

Lester Young: “Ding Dong”, recorded June 1949, released on Savoy Records. A much more widely-known track, Haynes is confident, assertive, and instantly recognizable. Haynes “dit-dit-an-dit-dit” solo break announces his arrival, while his intense, minimally-accented ride cymbal is a perfect platform for the soloists. Lester even plays half-time against Haynes’s relentless up-tempo. The three exchanges Roy shares with Lester drive home the point: Haynes has a complete conception of jazz drums.

Charlie Parker: “Ornithology”, recorded June, 1950. From Bird At St. Nick’s, released on Jazz Workshop Records. With Red Rodney on trumpet, Al Haig on piano, and Tommy Potter on bass. Haynes surrounds Bird’s wildly inventive, almost experimental solo with the same detailed tapestry of snare, bass, and ride cymbal that he used with Lester Young. The rhythmic unison between Bird and Haynes at the top of Bird’s first chorus tells the whole story— complete communication, empathy, and dialog.

Charlie Parker: “Embraceable You”, recorded June 1950, from Bird At St. Nick’s. Bird starts off with his signature “Embraceable You” motif, and eventually, Haynes answers Bird with 16th notes on the bass drum! This is a choice I’ve never heard another drummer make on a ballad, and it somehow works. It always sounds soothing to me, like Roy is telling us to take it easy, boom boom boom boom.

Sarah Vaughn: “Just One Of Those Things”, recorded August 1957, from Sarah Vaughan and Her Trio at Mr. Kelly’s (Roulette). With Jimmy Jones on piano and Richard Davis on bass, Haynes is the epitome of a ‘singer drummer’, fully supportive of Sarah Vaughan. But in the cracks, Haynes’s accents and tiny fills suggest the future. Speaking of Richard Davis and Roy Haynes….

Andrew Hill: “Wailing Wall”, recorded December 1963, from Smokestack (Blue Note). Richard Davis, bowing the melody, is the star of the track, but Haynes’s hypnotic cymbal sits at the center of Hill’s evocative, mournful composition. In December 1963, Roy Haynes was probably the only person who could have made this composition with these players come together so successfully. Bravo!

Jackie McLean: “Revillot”, recorded August 1964, from It’s Time (Blue Note).Trumpeter Charles Tolliver wrote the tune, and Haynes and McLean are joined by Herbie Hancock and bassist Cecil McBee. Haynes is now 39 years old, confident, assertive, and at home with the most advanced sounds of the day. Roy sounds so great— swinging and inventive, using some Afro-Cuban or Afro-Caribbean logic to hook up with up Herbie and McBee and push the music forward.

Gary Burton: “Portsmouth Figurations”, recorded August 1967, from Duster(RCA). With Steve Swallow on bass, and Larry Coryell on guitar, Roy had a part to play in the birth of fusion. Though it’s not a “fusion drum solo”, something about Roy’s energy fits perfectly with Coryell’s post-“Eight Miles High” vibe.

Archie Shepp: “Fiesta”, recorded January 1968, from The Way Ahead (Impulse). Haynes is liberated and joyous with Archie Shepp. Love their opening duet. When Ron Carter and Roy Haynes settle into the calypso-esque 10/4 or 5/2, worlds have peaceably collided. Shoutout to trumpeter Jimmy Owens, who takes a great solo here.

Alice Coltrane: “Leo, pt. 1/pt. 2”, live recording April 1976, fromTransfigurations (Warner Bros.). With Reggie Workman on bass and Ms. Coltrane on organ. This is undoubtedly the same drummer from Bird At St. Nicks, the bass drum alone is a giveaway. Haynes is gently embedding Alice’s music in more-or-less 4/4 swing, never boxing her in, using the most finely honed bebop wisdom. Every few seconds, the trio comes to a natural rise, Roy adds just the right amount of intensity, and then they move on. This track could go on forever, from one hill to another. Haynes’ solo on “Leo pt. 2” has a celebratory feel, as he explores some motifs, plays some fusion-inspired licks, and lightens the mood while maintaining the piece’s seriousness and intensity. Haynes’s single-headed multi-tom Ludwig kit, featured in print ads around this time (see above) sounds really great here. But then, Roy Haynes made everything sound great.

If I could add one more recording it would be Introducing Nat Adderley.

In an interview I read decades ago, Mr. Haynes was asked if he had a favorite recording of his playing.

He mentioned this recording. It's interesting because it's a very compact studio session. The songs are short, with wonderful arrangements coming out of Be Bop and into latter stages of Hard Bop.

Mr. Haynes "comping" is near perfect, with all of the commas, exclamations, and periods, shutting the door in all the right places behind the soloists.

Here is a link to that recording...

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=OLAK5uy_maigBGPAG8E2osGrw8dPeMD6mpjSylzLA

Thx for the post. Just started listenjng to Roy on "chasin another trane" from village vanguard and was stunned by how he and reggie hook up, so i'll be checking this Alice Coltrane recording out shortly