Jazz writer and historian Dan Morgenstern died on Monday, September 8th, 2024. Nate Chinen’s memories are heartfelt; Ethan Iverson shows how deeply influential he was, Lewis Porter finds him in a Sammy Davis, Jr. movie, and Barry Singer’s obituary from The New York Times is essential.

Like all of us, I read him for years, a truly trusted source, and I remember his smiling visage saying hello to the William Paterson seniors during our visit to the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers, years and years ago. He is missed, so I’ll let this essay be for Dan Morgenstern.

On the surface, vocalist Sarah Vaughan, guitarist Kenny Burrell, and pianist Andrew Hill don’t have much in common— Vaughan a beloved voice, Burrell a guitar icon, and Hill a patron saint of uncompromising artistry. But notice these albums:

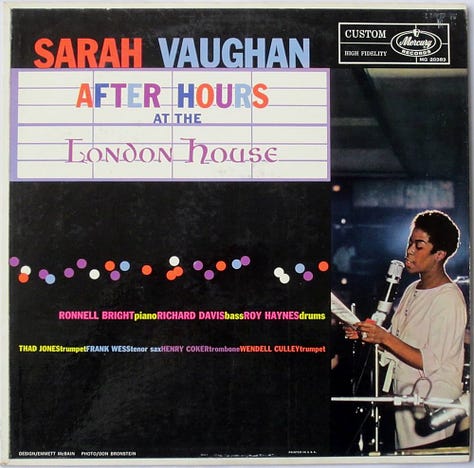

Sarah Vaughan: After Hours at the London House (Mercury/EmArcy), recorded March 1958;

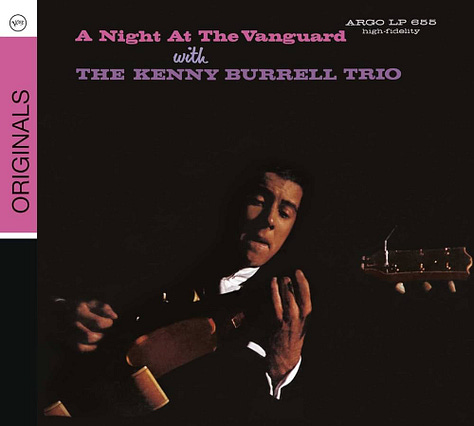

Kenny Burrell: A Night At The Vanguard (Argo), recorded September 1959;

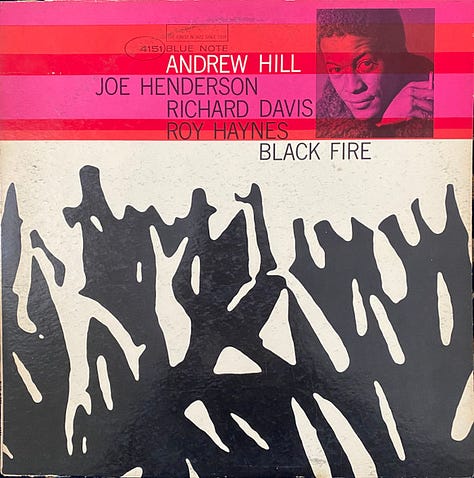

Andrew Hill: Black Fire (Blue Note), recorded October 1963.

All three feature bassist Richard Davis and drummer Roy Haynes. This trio of records are a joy to hear and fun to think about; thanks to Haynes and Davis, they’re a perfect illustration of how it’s all connected. This is the big tent. Let’s hear it for Roy Haynes and Richard Davis, bringing artistry and musicianship to such a diverse range of music!

(I’m double-dipping with Richard Davis on Chronicles— here’s a link to an early essay on his work with Thad Jones and Mel Lewis.)

In the not-officially-recognized but very real School of Modern Music, NYC campus, Class of 1944, Sarah Vaughan was valedictorian. While still in her teens, she played piano and sang with Earl Hines’s orchestra, where she met Billy Eckstine and Dizzy Gillespie, perhaps the two most influential figures in modern jazz. Later, Vaughan was a featured vocalist in Eckstine’s orchestra, and Gillespie was on Sarah’s earliest records. The three of them are forever linked.

As I learned writing this Kenny Clarke post, the memories of Eckstine, Gillespie, and Vaughan are scattered across the records my cohort glommed onto in our teens— for instance, John Coltrane’s “I Want To Talk About You” from Live at Birdland in 1963 is a Billy Eckstine tune. Wynton Kelly and Wes Montgomery’s “If You Could See Me Now” from Smokin’ At the Half Note in 1965 is based on Sarah Vaughan’s 1946 version, which was arranged by Tadd Dameron and backed by members of the Eckstine Orchestra. It must have been so meaningful for the audiences to hear those tunes. This was the music of their youth.

By the Fifties, Vaughan was a major star, recording for Mercury and on the road continuously. Roy Haynes was with her from 1949, Richard Davis joined in 1957, and both departed in 1958.

Writing this post, I finally began to hear how special Vaughan is, how her charisma and musicianship held everyone— the band, the guest soloists, the audience— in the palm of her hand. With Sarah, Davis and Haynes are far from the spotlight, but are fully involved in the music’s creation.

On “Like Someone In Love”, we know Vaughan is a jazz singer because her chorus leads smoothly into a letter-perfect Frank Wess solo. There are some signature comments and suggestions from Haynes’s bass drum, as well as a quarter note triplet from Davis that would soon become a portal to another world.

“Detour Ahead” is a tune from the era when jazz and pop weren’t synonymous, exactly, but were similar enough to create confusion. Davis and Haynes are certainly “playing the gig”— tasty and clean, setting up Vaughan and staying inside the lines— but turn up the volume and notice how much Haynes accomplishes just by an extra hi-hat splash after “suddenly I saw the light”.

Haynes and Davis get a heavy swing going on “Three Little Words”, leaning into the beat and pushing the time. Thad Jones, who would later place Richard Davis’s inside-outside aesthetic at the center of his jazz orchestra, takes a chorus— this is a jazz session, after all.

“I’ll String Along With You” is a straight forward ballad with Haynes and Davis staying right in their lane, but Thad Jones and the heavy beat return on “You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To”. Put on some headphones and listen to Roy Haynes’s intermittently-feathered bass drum.

“Speak Low” as a ballad was a surprise to me, with a wealth of details from Haynes— gentle double time and tiny orchestration changes (snare on the bridge, closed hi-hat for the double time, mallets on the coda, etc) showing his creative spirit and musicianship. On “All of You”, Haynes opens up for Vaughan’s second chorus, and then there’s Vaughan’s almost-zany version of “Thanks For The Memory”, maybe the most well-known part of the album.

As great as they sound with her, evolving and ambitious voices like Roy and Richard aren’t meant to support legendary vocalists on a permanent basis. After Hours at the London House is the last recording of Davis and Haynes made with Sarah Vaughan.

Kenny Burrell’s gorgeous tone, gift for melody, and thematically-unified records made him a household name in the Sixties. Richard Davis, like Burrell, would soon be a denizen of the recording studio, but when they recorded A Night at theVanguard, 18 months after After Hours at The London House, that was still in the future.

Is there a more infectious, inviting opener than “All Night Long”? It feels ready-made for a soundtrack. Roy Haynes is the star, with his left hand moving, Vernel Fournier-like, between the floor tom, high tom, and snare drum, barely altering his pattern once he gets it going. (I love hearing him casually turn his snares on.) Haynes wraps it up with his charismatic trades, featuring his inimitable snap-crackle, on a beautifully tuned four-piece drumset. His vocalizations, on the and of 1 and the and of 3, focus the beat and get us dancing.

“Will You Still Be Mine?” is taken at the Ahmad-Miles tempo, Haynes and Davis in lockstep when Burrell opens up. While Davis is straight-ahead and clearly outlining the changes, Haynes makes the unusual choice of sticking closely to a conga-esque pattern on the toms for Burrell’s solo.

The trio goes for a gentle cha-cha on “I’m A Fool To Want You”, and a pattern has emerged— three tunes, three distinct grooves. Hmm. A Night At The Vanguard was originally issued on Argo, a Chess subsidiary that was the home of Ahmad Jamal. So far, this record is Ahmad-adjacent: modern jazz that the insiders and the casual fans can enjoy equally.

Errol Garner is the author of “Trio”, another clue to what Burrell is going for. During Burrell’s first two choruses, Davis and Haynes are the epitome of class, taste, and swinging restraint. Haynes’s cymbal articulation is stunning.

On “Broadway”, Haynes picks up a mallet to play his tom tom beat, while Davis swings out, and on Benny Goodman and Charlie Christian’s “Soft Winds”, Haynes’s tom tom preoccupation, so striking and unusual that it had to be a conscious decision, maybe honoring a request from Burrell, is on display again. It’s not often we hear Richard Davis play some straight 4/4 blues in a trio, what a treat— picking him out here would make a great blindfold test

If you want to be modern and popular, play something from the Duke Ellington world. Billy Strayhorn’s “Just A Sittin’ and A-Rockin” is an inspired choice, tying together the strands of Burrell’s program.

Monk’s “Well You Needn’t”, right after the Strayhorn tune, makes the point perfectly: modern and popular. Haynes stays on his tom toms, while Davis is clearly inspired— this is the most “Richard Davis” he’s sounded so far. Again, Burrell keeps things relatively brief, taking the bridge out after the trades with Haynes, who has soloed on 5 of the 8 tunes on the album.

Andrew Hill moved to NYC in 1962, working with multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk (then still known as Roland Kirk) and recording with saxophonists Joe Henderson and Hank Mobley. The session with Mobley (No Room For Squares, an essential Philly Joe Jones performance) brought Hill to the attention of producer Alfred Lion, who presented the fully-formed Andrew Hill, visionary pianist and composer, on Black Fire, his stunning Blue Note debut.

According to Bob Blumenthal’s liner notes in the 2003 reissue, Lion enlisted Joe Henderson, Richard Davis, and Philly Joe Jones for the session, but when Philly Joe ultimately had a scheduling conflict, someone, presumably Hill or Lion, suggested Roy Haynes, pairing him with Richard Davis on record for the first time A Night At The Vanguard.

Haynes, born in 1925, was then in the process of reinventing himself as an ultra-modernist, appearing throughout 1963 on Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane sessions. Roy’s trademark clarity and precision, matched with an open mind and generous spirit, made him an ideal choice for Hill’s first album. He sounds so spectacular here.

On “Pumpkin”, Haynes and Davis are pliable and buoyant as the soloists spin poetry over the tune’s unconventional structure (I hear 8-bar A sections, plus an extra nine beats, surely others hear it differently, and only those inside the circle could say how the composer conceived it). Roy and Richard bravely let Hill’s purposefully disjunct and interrupted composition take a natural shape— if I were in their shoes, would I sense what Hill was going for and be able to help him bring it off? Haynes’s solo on this track is a highlight in his vast discography.

Less cubist, “Subterfuge” , the 24-bar form gestures obliquely towards boogaloo, with Haynes’s insistent pattern firmly grounding the tune in a Latin tradition. At times, the trio seems to willfully depart from each other, yet there is never a sense of disunity. A classic track.

“Black Fire” is Andrew Hill’s take on the soulful jazz waltz, a la Bobby Timmons’s “This Here”. As on “Subterfuge”, Davis and Haynes precisely outline the tune’s form while Hill seems to push against it, but there’s no clash of conceptions. Astonishing. This is, perhaps, the power of intention: because Roy Haynes and Richard Davis are intending only to play the hell out of Andrew’s tunes, support his concept, and make a great record, therefore, they can pretty much do no wrong.

The folk-like, singable melody of “Cantarnos” in medium-up 4/4 tells us to get ready for a modal burner in the Cedar Walton vein, but the quartet has other ideas. Hill plays nearly rubato, Henderson solos plaintively, and Davis eschews walking for lyrical counterpoint. Haynes plays his rolling eighth notes, the straight man to Hill and Davis.

“Tired Trade”, after Davis’s hypnotic solo, worrying those repeated notes until they transform, comes close to conventional swinging piano trio, but ultimately, Haynes holds it down while Davis and Hill explore the outer limits.

Is the lovely, lonely “McNeil Island” really named for the prison island in the US Pacific Northwest? After Hill’s apposite and suggestive turn, we’re treated to a Henderson/Davis duo, an emotional high point on the album. When Richard Davis, who died last year at 93, plays with a bow, European modernism and American Black music finally are united as equals. It’s perhaps the purest distillation of Richard Davis’s contribution.

Sounding not unlike Denis Charles, Roy Haynes introduces “Land of Nod” with an insistent 12/8 quasi-clave pattern. His touch on his ride cymbal during Davis’s single chorus is gorgeous— I cherish these Haynes/Davis moments of duo. Roy is not ‘just playing the cymbal’, he’s a complete percussion section, and ‘just playing the cymbal’ requires incredible skill and technique. Davis and Haynes go on to navigate Andrew and Joe Hen’s solos with the individuality and grace we’re now so familiar with.

Sarah Vaughan, Kenny Burrell, and Andrew Hill are a pretty wide range of experience and knowledge; certainly not everyone’s going to enjoy it all equally. But that’s not the point. The point is to see how connected they are, which really is a reflection on how connected we all are.

roy haynes is amazing!! i think the reason he is overshadowed by some of the others is it isn't easy to copy him, lol... the mallet on toms thing - just another example of breaking out of the box! thanks for the post vinnie..

A unique moment. Great post