In 1951, Kenny Clarke, the primary creator of modern jazz drumming, returned to New York after living in France for a few years. He got busy straightaway, in clubs, on the road, and, like Shelly Manne on the West Coast, in the studio. A consummate professional with a flexible, open-minded mien, Kenny Clarke was so at home in the recording studio that he eventually became a salaried A&R agent (what we now call a producer) for Savoy Records.

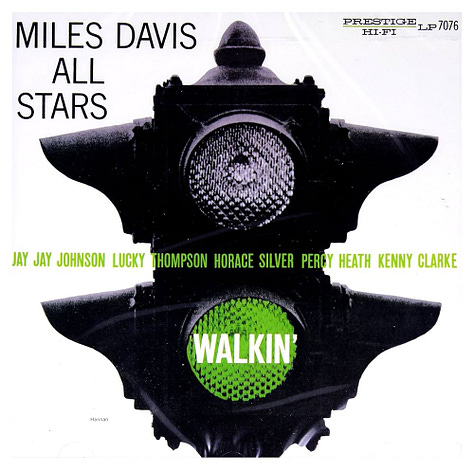

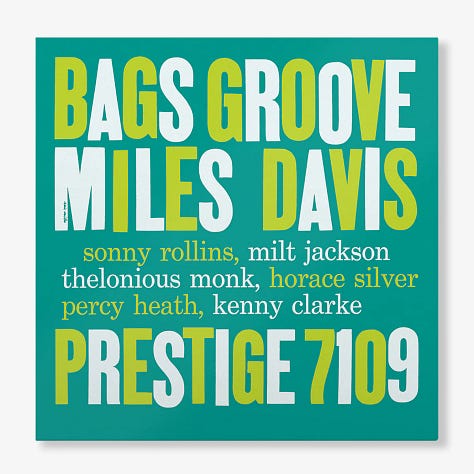

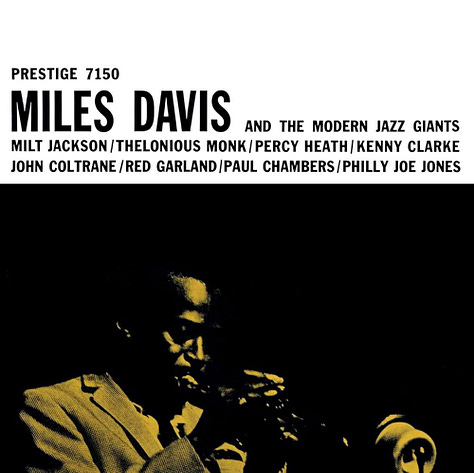

In 1954, Miles Davis, emerging from personal struggles and eager to take control of his future, tapped Kenny Clarke for four record dates at Rudy Van Gelder’s. These sessions— two in April, one in June, and one in December— were eventually collected on three Prestige LPs, Walkin’, Bags’ Groove, and Miles Davis and The Modern Jazz Giants, all streaming today. It’s on these records that we hear the birth of the mature Miles Davis conception, built around Kenny Clarke.

Like Jimmy Cobb on Kind of Blue, it might seem that Kenny Clarke is “just playing time”, but don’t be fooled— Clarke’s detailed tapestry, his humming ride cymbal and the endless flow of pops and feints from the snare and bass drum, is technical and conceptual mastery, a kaleidoscope of tension and release. As Paul Motian said to Ben Ratliff after hearing a Kenny Clarke-Miles Davis track, "There's so much music there, just on a snare drum. It's like a symphony to me."

As a young adult in the mid-1930s, Kenny Clarke had been a master dance drummer. It’s Kenny Clarke on the original “In The Mood”, by the Edgar Hayes Orchestra, for instance.

As the oldest member of the modern jazz cohort, Clarke had Black dance rhythms from the 1930s floating through all he played. Miles Davis built his 1954 recording sessions around the possibilities of Clarke’s ancient-to-modern sound. Here, Davis’s advanced bebop meets the Thirties grooves that started it all. Miles Davis’s choice of Kenny Clarke, Davis’s senior by 12 years, was a masterstroke.

The four 1954 Miles Davis-Kenny Clarke sessions:

April 3, 1954: Solar, You Don’t Know What Love Is, Love Me or Leave Me, I’ll Remember April;

April 29, 1954: Blue ‘n’ Boogie, Walkin’;

June 29, 1954: Airegin, Oleo, But Not For Me (two takes), Doxy;

December 24, 1954: Bags’ Groove (two takes), Bemsha Swing, Swing Spring, The Man I Love (two takes).

14 titles, 17 master recordings. On my Apple Music playlist, it’s less than two hours long. Great Miles, essential Kenny Clarke, and some of the most joyous, fun, and diverse jazz in the canon. I’ve chosen my favorite tracks, and assembled a playlist here; you can also click on the individual tracks.

April 3, 1954:

The recording studio as laboratory: Miles’s mute meets Clarke’s brushes for a session focused on mood, sound, and interplay.

The rhythm section was pianist Horace Silver, 24, and bassist Percy Heath, 29, led by Kenny Clarke, born January 1914, now 40 years old. They are the first classic Miles Davis rhythm section, setting the template for what was to come.

“Solar”: Clarke plays an ear-catching straight-eighth note brush pattern behind Miles, then swings out for alto saxophonist Davey Schildkraut. Saxophonist Bob Mover, who played with Kenny Clarke in France in the Seventies, told me that Clarke told him that the pattern originated with Miles and that Miles sat at the drums and demonstrated it for Clarke!

“Love Me Or Leave Me”: A low-volume burner. Clarke doesn’t play more than two bars without a little bebop hiccup, playing tough, conversational, chatty bebop brushes— perfect for Davis, Schildkraut, and Silver. The trades show how Clarke is different from Max Roach, who’d be composing a thesis, whereas Clarke plays simple phrases, staying in the flow of the time. Listen close for some telling bass drum accents— we can almost see the dancers.

April 29, 1954:

“Blue ‘n’ Boogie”: Dizzy Gillespie’s blues was the theme of the Billy Eckstine Orchestra, but Davis strips away all but the minimal riff that sits at the heart of the tune and plays it in unison with trombonist J.J. Johnson and tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson. By focusing on the riff, Davis puts the spotlight on the soloist and the rhythm section; by implication, on Kenny Clarke.

Kenny’s raucous yet precise hi-hat and snare intro, which wouldn’t have been out of place with Edgar Hayes in 1938, sets the mood. With his minimal kit (Clarke has a ride cymbal, snare drum, bass drum, and hi-hat, and nothing else), Kenny digs in, generating relentless forward motion, anticipating both Jimmy Cobb and Tony Williams, pushing the beat so that Miles and J.J. Johnson can take their time. The track nearly boils over during the backgrounds for Lucky Thompson’s solo; something authentic and spontaneous is captured here. Does anyone know the origin of those backgrounds? Dig Clarke’s quarter-note triplets on the snare behind Thompson right after the background. That’s some Elvin Jones stuff. Clarke was way ahead.

“Walkin”: Credited to music businessman Richard Carpenter, “Walkin” is transparently a tune by tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons called “Gravy”. Released by Prestige in 1950, Ammons’s “Gravy”, like Gillespie’s “Blue ‘n’ Boogie”, comes from the Billy Eckstine world. Both Ammons (“Blow Mr. Gene”) and Sonny Stitt, who plays baritone on the record, were stars of Eckstine’s band, while Art Blakey and bassist Tommy Potter, both present, were the Eckstine rhythm section. “Gravy” swings hard and has a tough swagger, one that clearly suggests the coming hard bop movement.

Paul Bley recorded “Gravy” in 1953 under the title “Teapot” with Charles Mingus and Art Blakey. Miles Davis first re-worked “Gravy” as “Weirdo” on his March 1954 Blue Note session, streaming now on Miles Davis Volume 2, joined by Horace Silver, Percy Heath, and Art Blakey. Two months after “Weirdo”, Davis gives us Ammons’s “Gravy” with a new intro and outro, now titled “Walkin”.

The long blues was a fixture of jazz LPs from this era; “Walkin” is the Platonic ideal of that sound. For this, we can thank Kenny Clarke, who, with “Walkin”, gave Miles his first hit.

After gorgeous hi-hat on the opening melody, it’s Kenny Clarke’s beat, precisely phrased and articulated on a small, high-pitched ride cymbal, that drives the band for a long straight chug of the blues. It’s Clarke’s beat really, that makes “Walkin” possible. Kenny’s high, clear cymbal sound is the first in a line that connects Connie Kay, Mickey Roker, Tootie Heath, Paul Motian, and Al Foster.

“Walkin” is minimalist, dance and trance music, something both Ahmad Jamal and Count Basie knew about. Like Jimmy Smith’s “The Sermon” and Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things”, it’s one sound with tiny variations. For 13 minutes, Clarke never deviates, never breaks character. He leads the rhythm section and they define a ‘studio’ mindset: ahead of the beat, minimal, clear, explicit. This is not a jam session, nor is it a live recording. This is a studio album, and that beat of Kenny’s that drives the tune is an artistic choice. It’s simply one of the greatest performances in all of jazz.

June 29, 1954

“Airegin”. Clarke has mastered Rollins’s composition for its debut recording, pushing the time, marking the form, staying at one dynamic, barely leaving the ride cymbal. During Davis’s first chorus, Clarke turns the cymbal beat around and doubles up on the eighth notes a la Shelly Manne and Tony Williams; on the out head, Clarke outlines Sonny’s melody on the kit, just like a player would do today.

“Oleo”. Kenny on brushes playing a Miles Davis arrangement of Rollins’ theme, one that owes something to Ahmad Jamal. Behind Miles, it’s a brush on a cymbal, a whisper of time; for Rollins, Kenny’s hi-hat makes a dramatic entry; for Silver, Kenny plays his symphony, brushes on the snare drum. This could have been a pop smash, so effective are the solos, sonority, and arrangement.

“Doxy”. Clarke’s bass drum sings through the initial head, punctuating Sonny’s classic melody and filling the spaces. When the solos start, instead of baring down, Clarke opens up, leaving room for the soloist, showing us how the music can be both light and heavy simultaneously. This is dance music.

December 24, 1954

“Bags’ Groove” take 1. Kenny supports the expansive, almost experimental vibe Davis is giving off by staying strong, he and Percy Heath pushing the time along. When Milt Jackson and Thelonious Monk enter, the mood changes entirely, yet we don’t hear it as a disruption, because Clarke doesn’t hear it that way. He just stays as he was, and we’ll follow his ride cymbal wherever it leads. Monk’s solo has been justly celebrated since 1955; stunning that Clarke and Monk had been playing together for almost twenty years by this point.

“The Man I Love” take 1. The conversation included at the beginning of the track gives us a glimpse at the intensity in the room. After Miles’s almost impish paraphrase of Gershwin’s melody, and Jackson’s heart-stopping four-bar break, Clarke’s entrance is thrilling, cool, controlled, patient. This is adult jazz, never more so than in Kenny’s support of Monk’s half-time interpolation of Gershwin’s melody. 70 years later, we can still hear the risk in this performance. I wonder if Miles, Milt Jackson, and Thelonious Monk felt so free to be themselves on that long-ago Christmas Eve because of the wisdom and empathy emanating from the bass and drum team, from Percy Heath and Kenny Clarke.

Bonus Tracks:

“Boplicity” (Miles Davis), recorded April 22, 1949 in NYC. With solos from Davis, Gerry Mulligan, and John Lewis on a Gil Evans arrangement, Miles is stepping firmly into the most progressive wing of the bebop movement. Clarke has a perfect understanding of Evans’s complex arrangement, while deftly switching from sticks to brushes throughout. Davis was 23, Clarke was 35: get the adult on drums.

“Ornithology” (Charlie Parker and Benny Harris), recorded May 1949 in Paris. Featuring James Moody on tenor, Tadd Dameron on piano, and bassist Barney Spieler. Clarke is strong, aggressive, and nearly disruptive, playing in the bomb-dropping style and kicking Miles around the stage. We get a sense of how experimental bebop was, and the large audience shows that it was also, sometimes, popular music.

“Woody’n You” (Dizzy Gillespie), recorded May 9, 1952. Miles is on the search for a meeting place between the unfettered, open-ended feel of his concerts with Clarke in Paris and the possibilities suggested by the Birth of the Cool. For this, he’ll need Kenny Clarke. Clarke plays at pretty much one volume for the entirety of the piece, bringing unity to the complex arrangement.

“Tasty Pudding” (Al Cohn), recorded February 19, 1953. With John Lewis on piano. Cohn’s writing, good as it is, is perhaps not right for Miles, though Clarke seems to be enjoying himself. Collected on the Prestige LP Miles Davis and Horns, it’s a worthwhile experiment and a fun record, one that shows just how outside the norm “Walkin” and the rest of the Clarke-Davis triumphs of 1954 really are.

“Diner Au Motel” (Miles Davis), recorded December, 1957, from Miles’s score to Louis Malle’s film Ascenseur pour l'Échafaud (1958). With a trio of Davis, Clarke, and Pierre Michelot on an 8-bar form, this is the track on which Paul Motian heard a symphony. Within the world of medium-up 4/4, brushes, snare drum, and hi-hat, Kenny Clarke shows that everything is possible: tension and release, tiny dynamic fluctuations, and ultimately, a kind of stillness and acceptance. There is endless depth in this music.

Great additional context from Mark Stryker, posted with permission:

Great stuff, thanks! Silver, Heath, and Clark were indeed a truly special rhythm section. The "Bag's Groove" LP is on my personal list of 10 favorite Miles records.

Worth noting that this threesome was a part of five other recording sessions in 1954 in addition to those with Miles. They first came together under Art Farmer's name for Prestige on January 20 with Sonny Rollins also in the front line. This is a favorite track of mine. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8eGisuHu2Y

Then there's a Savoy session co-led by Bob Brookmeyer and tenor saxophonist Phil Urso on April 30 and another Art Farmer date on Prestige on May 19 with Gigi Gryce. After that, they appear on a few tracks on the quirky Leonard Feather-produced "Cats vs Chicks" recording for MGM that pitted men against women in an adjudicated cutting contest on June 2. Finally, there's a Milt Jackson 4qt date on Prestige on June 16.

And that's it. The trio never recorded together again as a unit -- so eight dates in six months. Is there any evidence that they played together as a unit outside the studio on a gig?

—VS; in the Hennessy KC bio he mentions Horace subbing for Lewis at an MJQ gig at Newport!!!!!

This is criticism at its best — now I want to listen to these all again with your notes in mind. Thank you.