The new book about Chick Webb

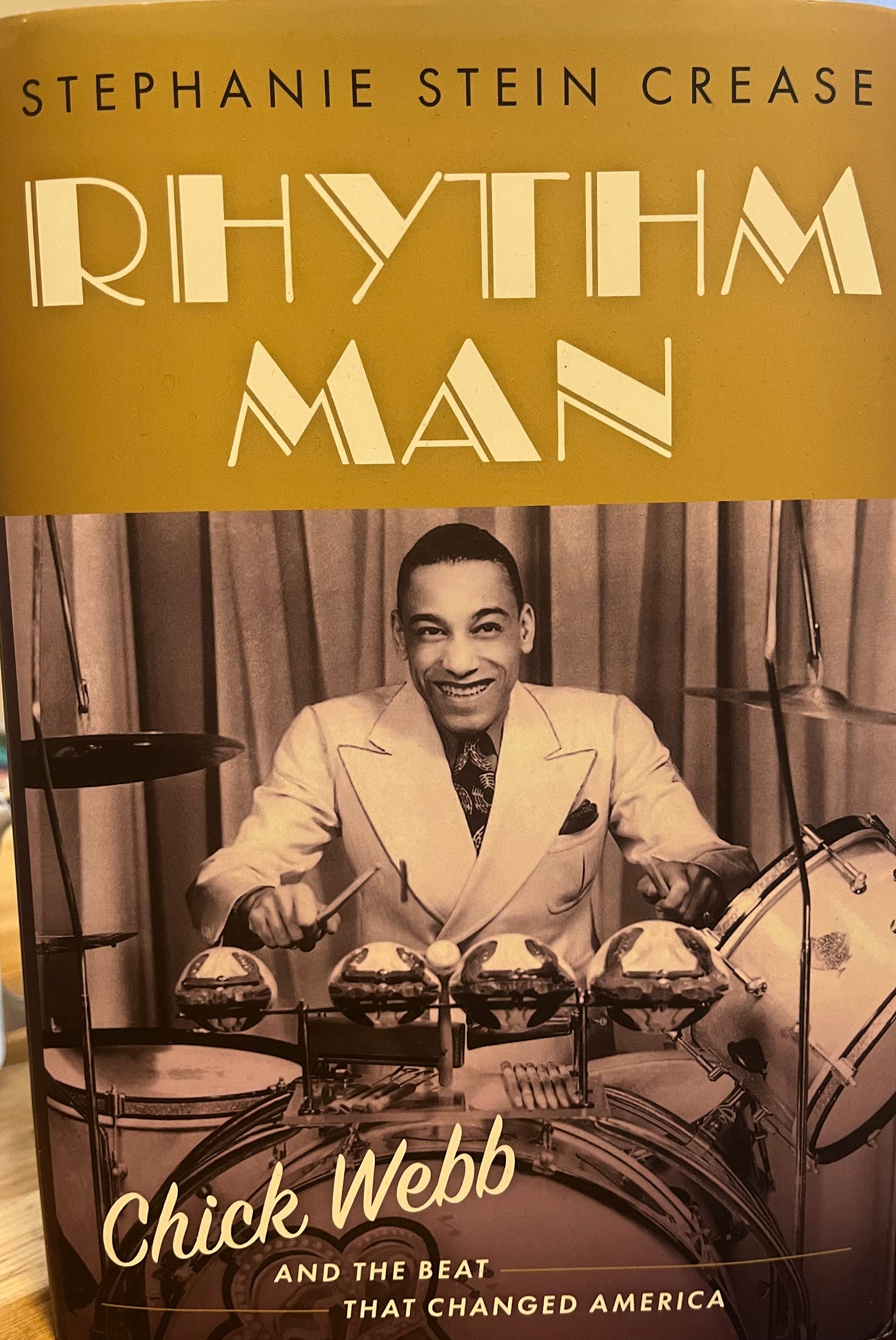

"Rhythm Man" by Stephanie Stein Crease is a must-read jazz biography.

Stephanie Stein Crease’s new full-length biography of Chick Webb, Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and The Beat That Changed America (Oxford) is essential. Buy it right here.

Crease’s book is an expertly narrated story of Webb’s life, detailing his career within the Black music world of the 1920’s and 30s, presenting a nuanced, rounded portrait of the master drummer. Rhythm Man is very much “The Life and Times of Chick Webb”.

Rhythm Man not only chronicles Webb’s life, but embeds Webb within the fabric of the Black community of Baltimore, and the day-to-day world of being a Prohibition-era working Black musician in New York. Mythical, hushed-tone, argument-ending locales— the Savoy Ballroom, the Roseland, the Paramount— are drawn into the light, fleshed out and made real: we meet the manager of the Savoy, the investors and backers of the Apollo Theater; we learn of their booking policies, nightly schedules, pay scales.

Effectively explaining how the world of Harlem nightlife was tethered to the daytime reality of taxes, real estate, business owners, and municipal government, Crease allows us to experience Chick Webb as both an ambitious professional and an innovative, avant-garde artist. Much praise to Stephanie Stein Crease for bringing off this tricky balancing act.

First things first: Crease firmly establishes that William Henry Webb was born in East Baltimore, on February 10, 19051 and was infected with “spinal tuberculosis, a chronic disease that affects spine development in children. He grew to be only four feet tall, with a deformed spine and a hump on his back2.” Webb had little formal schooling; was captivated by music; and was a working musician before he was a teenager. In 1925, Webb and guitarist John Trueheart3 moved from Baltimore to New York, on the heels of Eubie Blake and Blanche Calloway (Cab’s older sister), two Baltimore-born Black musicians who’d recently made significant headway in New York.

Webb began making the rounds, meeting musicians and sitting in, seemingly from the moment he arrived in New York. Completely devoted to finding success in the music business,4 Chick possessed unusual personal strength and faith in himself, allowing him to suffer setback after setback— problems with the musician’s union, indifference from the press, personnel turnover, being stiffed on the road, etc, all taken in stride.

Most intriguing are Crease’s details about the Harlem clubs and speakeasies which hosted jam sessions; this is where Webb started his career. I’ve read accounts of this world before, but never one so clear, so matter-of-fact. Ms. Crease admirably avoids romanticizing the time and place, yet allows the reader to be enchanted all the same. We cheer Webb on when he gets noticed at Harlem spots like the Rhythm Club— the unofficial Black musicians’ union, where unemployed or underemployed young innovators came and played in the hopes of making a connection, finding a gig5.

Webb was in the right place at the right time. He soon meets and befriends Duke Ellington, then 26 years old6, further along in the business, but essentially Webb’s peer. (It’s startling to meet Ellington as simply a guy going about his day, a young and ambitious professional, jumping at any chance that came his way, still on the verge of becoming ‘Duke Ellington’.) It’s Ellington who, in 1926, contracted Webb and his band, which included Johnny Hodges, for a long-term engagement at a club called the Black Bottom in midtown Manhattan.

This was the beginning of Webb’s career as a bandleader. It was only a year later— February 1927— when Webb made his debut at the Savoy.

Popular music in the Swing Era7 meant a ballroom, a tuxedo-clad big band, and men and women dancing to the band and holding each other. The origin of this practice— nattily-dressed couples, dancing the latest steps, to music played by an ensemble of 14-17 jazz professionals— was in Harlem, with roots in Black entertainment of the 1910’s and 20’s, coming to full bloom in the early 1930s.

The premier venue for this experience was Harlem's Savoy Ballroom. By 1933, Chick Webb and his Orchestra was the sound of the Savoy8. Thanks in part to the Savoy’s prominence in American social life, it was Chick Webb who became, essentially, the first widely influential drummer in American music9.

Before Gene Krupa, before Jo Jones, Buddy Rich, Max Roach, Art Blakey, and the litany of giants, there was Chick Webb. Before Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Artie Shaw, there was Chick Webb.

As prominent as Webb was at the Savoy, Crease makes clear that he was not yet the commercial success he hoped to be. When Webb gambles on a teenaged, unknown Ella Fitzgerald, hiring her as permanent addition to the band, the risk pays off with “A-Tisket A-Tasket”, a million-selling single released in the summer of 1938 and still heard today. Now, at last, Webb’s band was a national sensation, ready to go to the top.

Tragically, Webb had little time left. His chronic condition had been steadily worsening since at least 1936, just one of the many challenges Webb overcame. By the summer of 1939, the pain in his back had finally become debilitating, preventing Webb from touring with his band.

Chick Webb died at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, MD on June 16th, 1939, from complications of tuberculosis, while his orchestra, fronted by Ella Fitzgerald, was on tour without him. His funeral in Baltimore was one of the biggest ever held, attended by thousands, and Webb’s name is still attached to a youth center in East Baltimore, designated a landmark in 2017, with plans underway to fully renovate. Ella Fitzgerald is universally beloved, a major part of popular culture today; she mentioned Webb’s name and credited him for his contribution until the very end.

Gene Krupa was born 1909; Jo Jones, 1911; Kenny Clarke, 1914; Buddy Rich in 1917; Art Blakey was born in 1919; and Max Roach was born 1924.

1909 to 1924: a span of just 15 years, giving us drummers who invented and shaped the totality of the music’s history, from “Sing Sing Sing” to Charlie Parker, to Cecil Taylor, and all stops in between and beyond.

Each of these drummers’ names evokes distinct sound worlds; each of these players is a universe unto themselves. Yet they share an influence, share an experience that shaped their very notions of what jazz and a jazz drummer could be.

That influence is Chick Webb.

It’s all starting to make sense. Gene Krupa heard and saw Webb at the Savoy and named him as his number-one influence; Buddy Rich was perhaps the more adept student than Gene, stating plainly10 that Webb was his favorite player and perhaps the greatest player in history; Jo Jones was an idiosyncratic stylist probably from birth, but Jones got something from Webb. Is Webb present in Jones’ aspirational stage demeanor? It’s possible.

Meanwhile, Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey, and Max Roach all took something perhaps less concrete, less musicological, more social, more poetic from Webb; something about being at the center of a crowd and doing something special with that attention; advancing themselves and their audience; advancing music, jazz, and humanity at large.

In Rhythm Man, Roach describes the feeling of Webb’s bass drum resonating through his body and the excitement of the crowd; Blakey describes learning his press roll from Webb11 , while Ulysses Owens Jr. and Kenny Washington elucidate the broader points of Webb’s achievement-- Webb was coming up with ways to play with a big band (before they were even called 'big bands') we still use today12; he was both an uncompromising individual with his own voice, and a consummate professional who lived to play the arrangement and swing the band.

By being the common denominator between the Swing Era and the coming bebop revolution, Chick Webb might be the single most influential jazz drummer in history, even if the vast majority of listeners today don’t know his music.

But the larger story is that Webb’s records are good music; Webb’s playing has value even if no one was influenced by him. His music is great— fun, joyous, and focussed on musicianship— separate from its historical importance. I had so much fun listening to him and absorbing his playing in the past two weeks.

Here are 8 tracks that I focussed on. Special thank you to Kenny Washington and Ulysses Owns Jr., who mention several of these in Rhythm Man. All of them, save the Louis Armstrong track, are available on a release by GRP/Decca from 1994 called Spinnin’ The Webb, currently streaming on Apple Music.

“Hobo You Can’t Ride This Train”, with Louis Armstrong (recorded Dec 8, 1932, RCA). Armstrong hired Webb’s orchestra as his backing band in late 1932, touring with them into 1933. This track was a sizable hit, and though Webb himself is only momentarily audible (there are some tasty brushes just before Louis starts singing), we can hear just how swinging his band was at this early date, when the word ‘swing’ was only occasionally being applied to music.

“Don’t Be That Way”, written and arranged by Edgar Sampson (recorded November 19, 1934; Decca). Well-known as Benny Goodman’s theme song from 1938, Webb’s original version is fast and exciting, a clue to the overall atmosphere at the Savoy. Webb’s hits with the brass are well-recorded, and his solo breaks are forward-looking (they sound like Kenny Clarke to me). Webb is mostly playing the snare drum at this point; this would change by 1937.

“Clap Hands! Here Comes Charlie”, arranged by Edgar Sampson (recorded March 24, 1937; Decca). This right here— this is the Webb of legend. A three-bar intro, and then a heart-stopping four-bar drum break, Webb moving from snare drum, to future-creating tom-tom/bass drum combination, ending on beat 4 of the fourth measure; as hip, tasty, and slick as has ever been played. His beat is relentless; he changes texture for every soloist (notice the shades of ragtime and vaudeville under the piano solo). His three breaks going into the final shout (half) chorus— first on the snare, then with tom-tom/floor tom combinations, then snare, rims, and cowbell— are varied, exciting, virtuosic, and thrilling. Finally, the Chinese cymbal on 2 and 4 during the coda puts the band over the top. This is one of the greatest jazz drum tracks of all time.

“I Got Rhythm” (recorded September 21, 1937; Decca). With a front line of clarinet (Chauncey Haughton) and flute (Wayman Carver), here is Webb the progressive jazz artist. Notice Webb’s brushwork— full of detail, micro-variations, and incredible feel; he could make incredible music just keeping time. Two good clarinet choruses, with the bass and piano strictly in 2, give way to Webb soloing on the A sections with what I believe is a Billy Gladstone “Hand-Sock”, a sort of hi-hat you could hold in your hand.

“Harlem Congo” (recorded November 1, 1937; Decca). Webb’s tremendous drive and momentum must have been a boon to dancers. Notice how he subtly changes the texture— opening the hi-hat a little here, closing it there; a little crash here, then some grit from the snare. This is, as Kenny Washington and Ulysses Owens Jr. state, the very origins of big band drumming. Finally, the drum solo coda: 24 bars of snare drum, bass drum, and traps. Webb was the original swing drummer, but was Webb influenced by Jo Jones with Count Basie?

“Spinnin The Webb”, arranged by Benny Carter (recorded May 3, 1938; Decca). This is the earliest shuffle I’ve heard; no doubt Carter’s expert arrangement allows the shuffle rhythm to come soaring through. Rhythm guitarist Bobby Johnson is almost a second drummer, fully synced with Webb. For the coda, Webb goes to a backbeat on the snare with a shuffle on the small ride cymbal. At this very moment, hundreds of drummers are playing a variation on this beat.

“Liza”, arranged by Benny Carter Val Alexander13 (recorded May 3, 1938, Decca). Webb’s best-known track today, an utter masterpiece. Webb’s first solo is snare and bass; in the second we get some ragtime cowbells and tomtoms, sounding just like Baby Dodds, and in the split second before the brass enters, we hear Webb playing pure swing time; wonderful.

Carter’s Alexander’s arrangement is as masterful as Webb’s playing; indeed, it embeds Webb’s charismatic solos, infectious timekeeping, and innovative drumset orchestration at the very heart of the music. In a sense, “Liza” tells the story of Webb and the band, and, by extension, the Savoy, and maybe the whole Swing Era. The arrangement says, “This is CHICK WEBB! And this is HIS ORCHESTRA!! And now it’s TIME TO DANCE!!” Webb’s solo breaks have much in common with Baby Dodds’ Talking And Drum Solos, but the feeling is very different: Dodds was playing for the historical record; Webb is playing for the band, the dancers, the whole world, imbuing his music with the best kind of glamour, and deep aspiration.

Webb worked his whole life to achieve the artistic and commercial success we glimpse in this track. Perhaps this is why this cut meant so much to Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, and others. “Liza” is a joyous summary of Chick Webb’s music.

“Who Ya Hunchin’?” (recorded August 18, 1938; Decca). A forward-looking coda track, which features a loud (for the era) backbeat on the snare drum during the trumpet solo. “Who Ya Hunchin’?” and “Spinnin’ The Webb” are clearly predictive of Louis Jordan (a member of Webb’s orchestra) and the coming ‘jump band’ practice. In time, the drumming associated with jump bands and swing bands become the bedrock for rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and every backbeat-oriented music across the planet. Chick Webb is behind all of this.

Get Stephanie Stein Crease’s new book, check out the tunes, and have a ball. I learned so much from Rhythm Man and am deeply grateful for Stephanie Stein Crease’s hard work.

Respect and gratitude to Chick Webb.

Webb’s precise birthdate has been a subject of contention since the beginning of his career; Crease settles the question beyond (what I assume to be) reasonable doubt.

Crease is at pains to be very clear about Webb’s disease, as it has long been a source of misunderstanding, sometimes said to be related to a childhood injury, other times described as a congenital condition.

Trueheart was later a stalwart of Webb’s orchestra and close friend of Webb’s.

Tenor saxophonist Teddy McRae was a member of Webb’s orchestra, and is extensively quoted, from interviews he gave in the 70s for the Jazz Oral History Project. It’s startling and wonderful to read eyewitness accounts of events that transpired nearly 90 years ago.

New York drummer Tommy Benford— a name well-known to Phil Schaap listeners— shows up here, in about 1926, playing with Willie “The Lion” Smith and trying to help out Webb. Drummers Kaiser Marshall and Sonny Greer are also presences at various points, and a scene of Harlem drummers almost emerges from the text. There is certainly much, much more to learn about these gentlemen.

Webb himself was only 21 years old at the time.

Dates for the Swing Era vary widely— but let’s go with 1935 (when Benny Goodman went national) to 1948 (when Billboard’s new designation “rhythm and blues” was first used).

Crease includes some dance history, even venturing the meaning of swing in a dance context (it apparently refers to the partners separating—“swinging out”— from each other, improvising, and returning; a move we’ve all seen in movies).

This is a complicated assertion; certainly, drummers Warren ‘Baby’ Dodds, Zutty Singleton, Tubby Hall, Paul Barbarin, and others were known, heard, respected, and imitated from the early 1900’s on. But Webb was different— he was a national star (if only briefly), and being in NYC placed him at the center of everything in a way Dodds, for example, never was. True, Krupa, Roach, and Blakey credit scores of players, including Dodds, Singleton, et al; and I am in no way suggesting that Dodds, Singleton are not great and important players. However, Chick Webb was, in a sense, a subject on which everyone could agree, and by whom everyone was affected. The impression I get from Rhythm Man and from listening to records is that Webb expanded the scope of what was possible for drummers— on the drumset, in music, in the music business, and in the culture.

“And I think that the greatest drummer that ever lived was Chick Webb. He was my favorite drummer.” Buddy Rich, quoted in Rhythm Man, page 158.

Blakey told the story often that Webb told him to “roll to 100”; that is roll for 100 beats, as opposed to 100 strokes. Put the metronome at 100 bpm, and count each click, from 1 to 100. Elvin Jones mentions to Art Taylor in Notes and Tones that a 5-minute roll (i.e. a roll to 200 or 300, depending on the tempo) is something for a young drummer to aspire to. Tony Williams of course would feature a more-or-less unadorned double-stroke roll as part of his shows, sometimes playing the roll for two, three, or more minutes. And so on. The “roll to 100” is a glimpse at both drummer folkways and early drum pedagogy.

I think the concept of playing unison with the band, which evolved into the system of setting up hits, orchestrating the arrangement on the drumset while swinging the band—the whole Mel Lewis apparatus— was spread by Webb. Undoubtedly it was an evolving consensus across music in the early 20th century, but Webb was the drummer to dig; even when Webb wasn’t nationally known, those who knew, knew. On the earliest Webb sides where he can be heard, like “Heebie Jeebies” from 1931, Webb plays the brass break exactly with the brass on a choked crash cymbal. It’s hip, tasteful, exciting, and opens the doors to possibilities.

Thank you Ms. Crease for pointing out this error!

Vinnie, your enthusiasm for this book, for Chick Webb, and for the music permeates your writing. Bless you, it's infectious and makes me want to read the book and inhale the sounds! Keep on keeping on!

Excellent essay and a great recommendation. Just ordered the book. Thanks!