This Is New

Listening to the first three Chick Corea albums

I’m as nervous about the election as you are, but I’m proud to be voting for Kamala Harris, a vote for our future.

I was at a session the other day and someone asked: “What was Chick Corea’s first album as a leader?” We suggested a few titles, but no one was certain. Of the Big Four pianists— McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Keith Jarrett, and Chick— Corea’s early story is the least-known to me, and maybe the least-known in general.

I better get this together. Corea looms large, his absence still catches me off guard. It’s a cliche that to know the present and the future, you have to know the past, but it’s also true. Time to get some bearings on Chick Corea. There’s a story here.

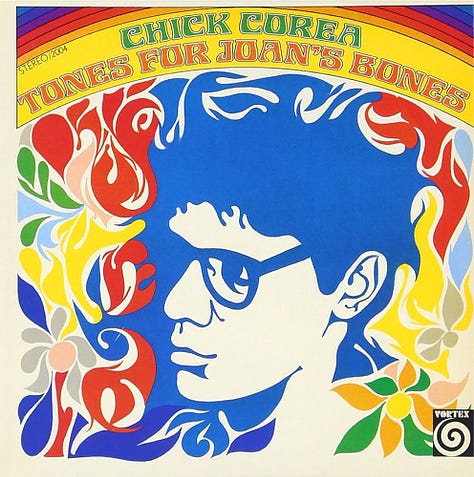

A glance at the Lord Discography and Wiki says that Tones For Joan’s Bones on Vortex, an Atlantic subsidiary, is the first album by Chick Corea under his own name. Prior to that, Corea had been active in Latin jazz circles with percussionists Mongo Santamaria and Willie Bobo and flautists Herbie Mann and Hubert Laws. In 1964 and 1965, Corea appeared on two dates by trumpeter Blue Mitchell for Blue Note, The Thing To Do and Down With It (both with Al Foster on drums).

Corea’s appearances with Blue Mitchell meant that he was one of the best young musicians in NYC, circling around the scene we’ll glimpse on the soon-coming McCoy Tyner/Joe Henderson Slugs’ date with Jack DeJohnette and Henry Grimes. Years later, Chick would become, in a sense, that scene’s breakout star. Corea’s vast discography as a leader begins like this:

Tones For Joan’s Bones (Vortex, recorded late 1966, released maybe late 1967?), with Woody Shaw, trumpet; Joe Farrell, tenor saxophone; Steve Swallow, bass; Joe Chambers, drums.

For his debut, Chick assembled a band that could do it all— Farrell was to be one of Chick’s closest comrades, Shaw was in Horace Silver’s group and played on Larry Young’s Unity (Blue Note, 1965), Swallow had cracked open the future of jazz piano with Pete LaRoca on Paul Bley’s Footloose (Savoy, 1963) while Joe Chambers, composer and drummer, had contributed vitally to groups led by Freddie Hubbard, Andrew Hill, and Bobby Hutcherson. Tellingly, Swallow and Chambers are associated with two pianists working in parallel to Corea: Swallow with Steve Kuhn, Joe Chambers with Stanley Cowell.

Let’s see it in a list. For his first session, Corea assembled a band with connections to the following pianists: Horace Silver, Paul Bley, Andrew Hill, Steve Kuhn, and Stanley Cowell.

Up first is “Litha”, still in the repertoire today. Why not begin your recorded legacy with a masterpiece? Yeah Chick! Chambers and Swallow navigate the transition from 6/8 to 4/4 with grace and ease, and we get classic solos from Farrell, Shaw, and Corea. Swallow’s low E launches the 4/4, and Chambers never repeats an idea, spurring on Chick, Shaw, and Farrell for a bravura performance. The quintet gives a more-or-less straight-ahead reading of “This Is New”, a seldom-heard Kurt Weill tune, with Chambers and Swallow swinging relentlessly and some lovely eighth-note lines from Corea.

On Side 2, “Tones For Joan’s Bones” is played by the rhythm section, with Chambers on brushes all the way, and Swallow featured for two choruses, the whole track firmly in the Bill Evans world. The record closes with “Straight Up and Down”, a modal burner driven by Chambers’s ride cymbal with a stunning Farrell solo and an essayistic Joe Chambers moment.

Tones For Joan’s Bones is a great slice of Sixties jazz, perhaps the closest Corea ever came to a hard bop record. Steve Swallow and Joe Chambers, still with us today, are standouts. Corea was fond of band reunions and revisiting old material; it’s too bad he never got around to re-assembling a version of this group.

Now He Sings, Now He Sobs (Solid State, recorded March 1968, released later that year), with Miroslav Vitous, bass; Roy Haynes, drums.

As time goes on, Now He Sings, Now He Sobs takes on an ever-greater luster. This is the essential Chick Corea album, now and always. Drummer Roy Haynes, 43 years old in 1968, now nearing his hundredth birthday, is the X-factor that puts Now He Sings over the top. There’s no better single disc to introduce a listener to Haynes’s magic. Haynes and Corea were first acquainted in Stan Getz’s band, but it was Roy who hired Chick for a week at Slugs’ sometime in 1968, planting the seeds for Now He Sings.

My generation knows the 1988 CD version of the record, 13 tracks kicking off with “Matrix”, but the original release was just five tunes, and started with “Steps-What Was”, a fast, McCoy-like 12-bar blues (“Steps”) that goes into a quasi-“La Fiesta” 6/8 Spanish feel (“What Was”). Haynes and Vitous are in perfect lockstep, and Miroslav’s tone blends enchantingly with Haynes’s flat ride cymbal. Side A closed with the “Matrix” we all know and love, as wow-inducing as ever. All respect to Roy Haynes.

“Now He Sings, Now He Sobs” is a straight-eighth 3/4 with a cycling form. Haynes’s military snare at the top catches my ear, and the unison piano/bass lick at the end wouldn’t have been out of place in the Elektric Band. “Now He Beats The Drum, Now He Stops” begins with an extended solo piano improvisation before becoming a medium-up version of Irving Berlin’s “How Deep Is The Ocean?”, re-harmonized and with Corea’s own melody. The album ends with the improvised “The Law of Falling and Catching Up”; at this stage, free improvisation was a major tool in Corea’s toolkit, one he would use extensively in the near future; Vitous and Haynes are both totally down.

Everything about Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, from the poetry-adorned album jacket to the pristine recorded sound, announces Corea’s arrival as a major artist. Only his second date as a leader, Chick not only delivered a perfect summary of the cutting edge circa 1968, he also debuted his own artistic persona, while making room for a timeless Roy Haynes performance. Now He Sings easily connects to much of Chick’s later work— Spanish vamps, bass/piano unisons, advanced blues, and aspirational poetry were all a part of the first Chick Corea Elektric Band album in 1986, for instance.

On another note: shockingly, neither Miroslav Vitous nor Roy Haynes were originally credited on the album! In fact, the pictures of the LP on discogs.com have a hand-written note listing both Miroslav and Roy. And who else thinks that “Matrix” is a better album opener than “Steps-What Was”?

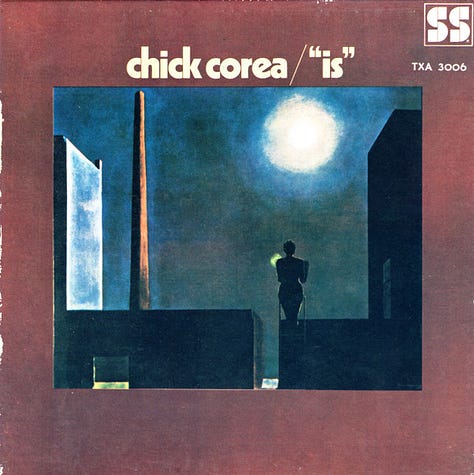

Is (Solid State, recorded May 1969, released later that year) with Woody Shaw, trumpet; Hubert Laws, flute and piccolo; Bennie Maupin, tenor saxophone; Dave Holland, bass; Jack DeJohnette and Horacee Arnold, drums and percussion.

Perhaps the least-known of Chick’s early work, Is is the second and final recording of Chick with Woody Shaw, and the first release to feature Corea, Dave Holland, and Jack DeJohnette, one of our classic rhythm sections. More to the point, the music is startlingly avant-garde. The title track, nearly thirty minutes of free improvisation, is so unrestrained that at times it’s nearly chaotic or cacophonous, two adjectives one would never apply to later Corea music. I’ve written about Is here, for drummer Horacee Arnold.

“Is” starts with a percussion ensemble of Chick, DeJohnette, and Horacee Arnold, with Hubert Laws floating through the scene before Shaw joins the drummers to blast down the walls. Chick moves between piano, percussion, and Rhodes, and cohesive, exciting segments emerge, such as when Holland and DeJohnette open up into 4/4 swing; the final trio statement by Corea, Holland, and DeJohnette is undeniable. This was where the music was going.

Holland’s own “Jamala” likewise feels on the verge of unraveling, with the horns nearly overwhelmed by Arnold and DeJohnette, but on “This”, the Corea-Holland-DeJohnette sports car eases into top gear, before the final piece, “It”, 30 seconds of virtuosity from Corea and Laws in duo, gets Is across the finish line.

When I was younger, I would have dismissed Is and similar things with a simple “It was the times” hand wave, sparing myself the job of actually listening to and considering the music. Now I realize how much courage was needed to make a record like Is, what an uphill battle Corea and his bandmates faced.

Imagine being a jazz fan from the suburbs or the sticks in 1969, when “the Sixties" had still not reached many (most?) parts of the USA, and dropping the needle on side 1 of Is. It’s a tough listen now— what did it sound like 55 years ago? Today, society condones and accepts this type of music. If this is your thing, congratulations— there’s an international infrastructure of conservatory programs, grants, record labels, even a circuit of well-funded concert series that you can tour, if you’re lucky.

Not so in 1969, not even close. The main thing I hear on Is is bravery.

After Is, a few years passed before Corea became the audience-thrilling dynamo we all loved. First, Chick became a full-time member of the Miles Davis group, joining Wayne Shorter, DeJohnette, and Holland in the “Lost Quintet” of 1969, and staying with Davis until the fall of 1970, all while developing his identity as an uncompromising experimentalist in a trio with Dave Holland and drummer Barry Altschul. When Anthony Braxton joined them, they called themselves Circle and made some well-loved recordings for ECM and Blue Note.

Around 1973, Corea, newly enrolled as a Scientologist, re-booted his musical identity as the leader of a reimagined Return To Forever. What had been a woodwind and voice-driven Brazilian group was relaunched as a muscular, guitar-forward fusion juggernaut, to much success. As Return To Forever grew and prospered, Chick put out a series of albums on Polydor, each with a corresponding theme and costume— The Leprechaun (1976), My Spanish Heart (1977), Mad Hatter, Secret Agent, and Friends (all released in 1978). By now, Chick’s experimental impulse was most visible in his profligate and promiscuous band-forming and project-starting; much like his comrade Herbie Hancock, nothing was off-limits, everything was fair game, and new technology was immediately embraced. From here on out, with various bands— Elektric, Akoustic, Time Warp, Origin, New Trio, Five Peace, Vigil, and all-star trios and quintets honoring Bud Powell, Bill Evans, and others— Corea never stopped developing and expanding his stature and audience.

Somehow we can hear most of Corea’s subsequent developments, embryo like, in these three early releases. All our futures are truly encoded in our present.

One small piece of the puzzle: why is Chick playing with so many musicians who were associated with Horace Silver? He probably explained it a hundred times, but I heard it in a Zoom chat he did with Wynton Marsalis, very near the end of his life during the early COVID lockdown. He had a band when he was a student in Massachusetts that played Horace Silver tunes. When he got to NYC, the guys in Horace's band wanted to work more than Horace did. Chick knew the book and, I presume, worked fairly cheap. So he'd be the pianist in the Junior Cook Quintet or the Blue Mitchell Quintet. And so on to Woody, Joe Hen and Maupin.

Great piece - Chick Corea's debut is jaw-droppingly good and should be way more celebrated than it is - a daring statement. I also did want to note that it's Joe Farrell as opposed to Henderson on the album.