The English drummer and composer Tony Oxley, who died yesterday, December 26, 2023, was an important jazz drummer who perhaps made his mark most deeply as a part of the global community of improvising musicians.

In his long career, he played with Sonny Rollins, collaborated frequently with English compatriots Derek Bailey and Evan Parker, toured with Bill Evans, and had long musical partnerships with Bill Dixon and Cecil Taylor.

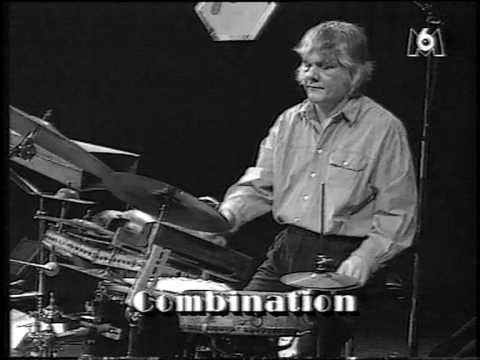

Here’s a YouTube link of him playing a two-minute drum solo:

I love this clip. It’s a complete piece of music, full of energy, contrast, and humor. It reminds me that an ‘improvised music’ drum solo can be a lot of fun. Bravo, Tony Oxley!

Oxley’s graceful sweeps around his unconventional kit are unique to him, yet underneath, he’s playing the common language, putting his own spin on rudiments and jazz phrases.

I’ve always loved his sound: round, full, and deep, even when he’s scraping a cowbell or rolling on a bongo. His roots in bebop and other ‘conventional’ styles sit just below the surface. Oxley is one of those drummers— choose your favorite— who was always radical and traditional: no matter what he played, he always had a great feel and a beautiful sound.

He’s one of the musicians who first marked the territory at the intersection of jazz, modern composition, and free improvisation. This sound is a big part of the music in 2023, and its sources are wide-ranging. Tony Oxley is one who pointed the way.

Oxley was born in Yorkshire, England, in 1938. Once again, Modern Drummer magazine picks up where other journalism leaves off. Journalist Simon Goodwin interviewed Oxley at length about his early years, and his ideas about improvising. Published by MD in April 1990, the story is currently available via a digital subscription at moderndrummer.com

To connoisseurs, Oxley is known for being 1/3 of Joseph Holbrooke, one of the first (1965) all-improvising ensembles in England, maybe even one of the earliest ever. ‘Joseph Holbrooke’ was, amusingly, the name of the trio, not the name of a musician in the trio; it was comprised of guitarist Derek Bailey, bassist Gavin Bryars, and Oxley.

Later, Oxley became a house drummer at Ronnie Scott’s, the famous London club, where he worked with Sonny Rollins, Johnny Griffin, and many other touring Black jazz musicians. Here’s his quote about Sonny Rollins from the MD interview:

“It's a long time since I played with Sonny, but when I did there was a change in my philosophy of music. This was in the late '60s, and at the time I was predicting that this would happen, but I never expected it to come from the direction it did. It was 100% because of Sonny Rollins. I was asking myself some very heavy questions, and he answered them—purely in his playing; it had nothing to do with speaking… it was an aesthetic thing in a way.

It's a matter of being able to get all the energies working in the same direction at the same time—to have all your energies properly developed and to have them all sensitive and working harmoniously in the circumstances you are in with the people you are working with.”

In high school, I loved the very first John McLaughlin album, Extrapolation. Tony Oxley is on the entire session, playing a regular four-piece drumset. His top-of-the-beat feel, virtuosic four-way coordination— listen to all that hi-hat independence!— and unique sound brand him as a state-of-the-art Sixties jazz drummer.

But by the Eighties, Oxley had discarded the snare drum and replaced it with a bestiary of quick-decaying tomtom-like sounds, including old Chinese toms with tack heads. His iconic giant cowbell, which he commissioned, was positioned next to his ride cymbal and hovered over the kit like an idol, a physical representation of Oxley’s unconventional thinking.

I’ll be reading others for a deeper dive on Tony Oxley, but these cuts are a good starting place:

John McLaughlin, “Extrapolation”, from Extrapolation, (Polydor, 1968). Navigating the transitions as smoothly as Dannie Richmond, while pushing John Surman and McLaughlin to the top, Oxley is essential to the success of McLaughlin’s first album. All the ‘progressive’ music scenes in England were blended at this time, so there’s something Cream-adjacent to Oxley and McLaughlin here, which was catnip to my teenage ears.

Tony Oxley, “Preparation” from The Baptised Traveller (CBS, 1969). This is the thing called ‘improvised music’, at first blush not far from AACM experiments. A closer listen, especially to Oxley, brings out the English progressive music lean.

Bill Evans, “Nardis”, live in Ljubljana, 1972. Astonishing how seamlessly Oxley’s radical conception fits with Bill Evans and Eddie Gomez. After the drum solo, Evans’ trio really could be Chick Corea’s Circle. Oxley’s solo is free, but still sounds like “Nardis”.

Tomasz Stańko, “Morning Heavy Song” from Leosia (ECM, 1997). A tough, grown-up tempo that Oxley handles with aplomb, perfectly blended with his out-of-time commentary. Masterful playing.

Cecil Taylor: “Berlin Conversation 1”, from Conversations with Tony Oxley (Jazzwerkstat, recorded 2008/released 2018). There’s more breath and space then I would have guessed; clearly, Oxley and Taylor had a deep connection and special chemistry. I’ve been listening to this for most of the afternoon, and while I’m not versed in Taylor’s discography, this must be one of his and Oxley’s most engaging releases, at least from this era.

This brings up a brief personal recollection: The singer-songwriter and playwright Stew (Passing Strange) was a devotee of Cecil Taylor and Tony Oxley. When he would talk about their duo shows, Stew would always imitate Tony’s signature gestures at the kit and exclaim “Oxley just did the dishes!” This became a shorthand in the band: during a show, Stew might request an Oxley-ish texture with an on-mic call for “Vinnie Sperrazza, do the dishes!”

To understate: there’s a lot of great music out there, and I’m want to get to it all. I certainly wish I’d written this essay while Oxley was alive to appreciate it1, but that’s life.

In 2024, let’s keep noticing the incredible music in front of us, the great players alive right now, playing tonight.

All gratitude and respect for Tony Oxley.

A few notes about the records you mentioned: Tony considered Extrapolation to be a "pop record" that he did as a favor to McLaughlin and because he was completely broke at the time. Not to take anything away from his playing; he was the only one in England who could play McLaughlin's music on drums at that time and he was aware of that.

In 1972, after a few gigs, Bill Evans offered Tony to be the permanent drummer in his trio, but Tony didn't want to commit for more than 6 months; that wasn't enough for Bill Evans.

And at this duo gig in 2008 I shared the evening with the Oxley/Taylor duo (I played with the Uli Gumpert Workshop Band). Apart from the fact that Cecil wanted to renegotiate his fee shortly before his performance (but the organizer Ulli Blobel routinely let that go to waste), I was also amazed by Tony's playing that night. There was a lot more electronics than drums, and he had also lightened up his drum set because he thought he was too old to carry it around.

He was one of my heroes and his music was and is a great inspiration.

thanks vinnie! i too was influenced by the john mclaughlin album - extrapolation with tony on it... awesome playing and drummer.. never got to see him play since he was in the uk the whole time mostly..

michael griener - thanks for those additional notes.. very interesting!! i have seen han bennink a few times and admire his approach... i am much more straight ahead drummer then either of these cats, but i really dig what both of them do...