“What appears in the rearview mirror as a sudden disjunction, a leap from the old to the new, could hardly have happened without a long series of smaller shifts and alterations making it possible. The role of the chronicler is to bring this trail of events to life, revealing the gradual, organic processes behind the apparently spontaneous arising of the new.”

Ted Gioia, Music: A Subversive History, 2021

TURNS: PAUL MOTIAN, 1963-1965

Part 1 of 2

At the start of 1963, Paul Motian was just one of many dozen swinging New York City drummers, best known at the time for supplying tasteful and open textures in support of the famous collaboration between Bill Evans and Scott LaFaro. Certainly, no contemporary observer would have predicted his future status as avant-garde icon: an innovator name-checked by Jack DeJohnette and Jeff Watts; an influential composer and bandleader; even the subject of his own documentary, the wonderful 2021 film Motian in Motion, directed by Michael Patrick Kelly.

Over the course of two years, four LPs with three pianists- Paul Bley, Bill Evans, and Mose Allison- tell a story of rapid growth.

Paul Bley: Paul Bley With Gary Peacock

Bill Evans: Trio 64

Paul Bley: Turning Point

Mose Allison: Wild Man On The Loose

In Part 1 we’ll take a deep dive into Paul Bley With Gary Peacock and Trio 64, with the aim of making you want to listen to these records again right away. Occasionally, I widen the frame and gently place these sounds in a bigger context of jazz, American music and American culture.

PAUL BLEY: PAUL BLEY WITH GARY PEACOCK (ECM 1003)

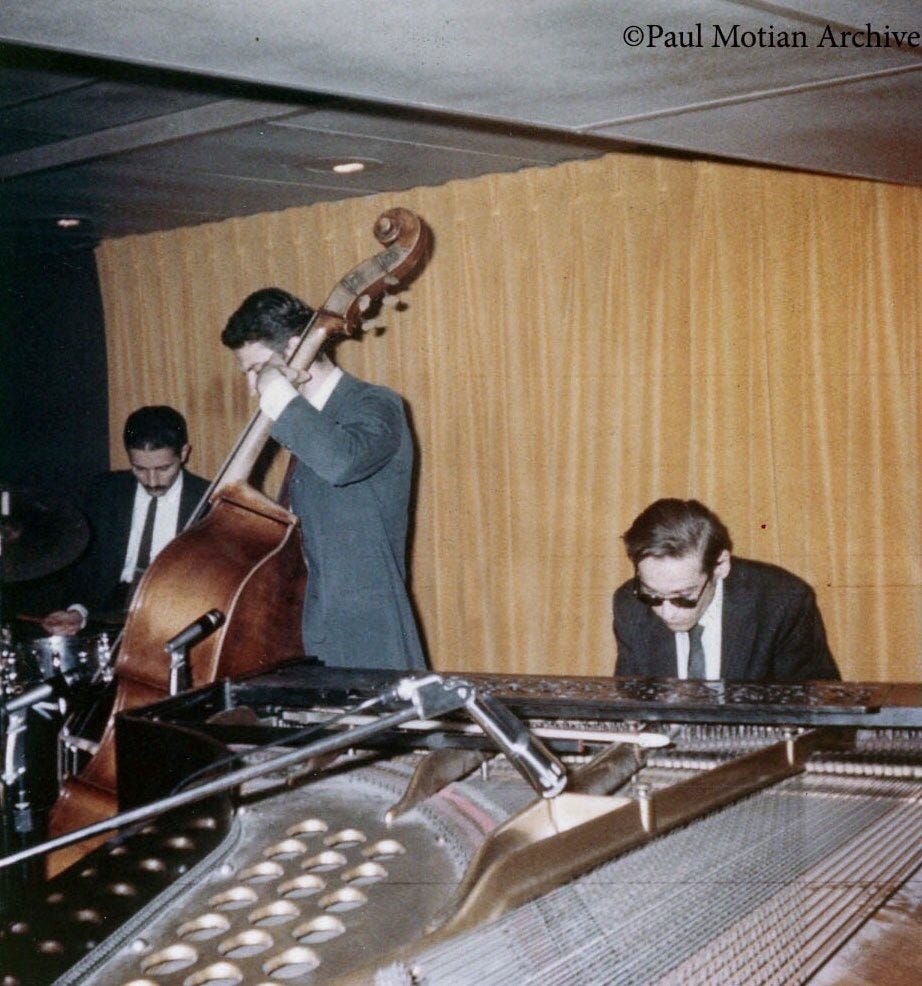

Paul Bley’s home studio, New York, Saturday, April 13th 1963; Paul Bley (p), Gary Peacock (b), Paul Motian (ds). Released 1970.

The first recording of Bley, Peacock, and Motian was recorded at Bley’s apartment in 1963. Seven years later, Bley sold the tape to producer Manfred Eicher, and that tape, with a few additional tracks from a different session with drummer Billy Elgart, became the third album released on Eicher’s brand-new ECM label.

The material was simple and well-chosen to feature everyone’s strengths: two medium-up blues, a medium-up standard, a ballad, and a Peacock modal tune with a melodic fragment.

For Motian, this session is more of a ‘foundational experience’ than a mature statement. His approach is more like the way he played with Bill Evans than the way he played in the future.

1.) Blues (Bley, actually “The Turnaround” by Ornette Coleman)

Peacock and Bley= King Kong vs Godzilla. Titans Of Deconstruction! Motian stays on brushes, playing the straight man, keeping the momentum going. A few tell-tale noises in the final piano chorus before the out head foreshadow things to come.

2.) Getting Started (Bley, actually “I Can’t Get Started” by Vernon Duke)

We have entered Bley’s signature romantic, wistful, surreal harmonic environment. Although Motian doesn’t play anything which would be out of place in any conventional ballad performance, his openness to Bley and Peacock is informing his every decision. This is clearly a drummer that “gets the music”.

3.) When Will The Blues Leave? (Ornette Coleman)

Paul Bley’s theme. By this time, two master drummers, Billy Higgins and Pete LaRoca, had both left their fingerprints on this song. A quick look at their approaches illuminates evolving ideas about new possibilities in jazz drumming.

When Bley played the tune with Billy Higgins and Ornette Coleman at the Hillcrest Club in LA, Higgins connected the new language of Ornette to jazz’s past with beautifully played, joyful, and supportive Max-inspired comments in the spaces in the melody.

Pete LaRoca’s Latin influenced, charismatic, ultra-modern conception was an integral part of the classic “When Will The Blues Leave?” from Bley’s Footloose! 1album. Pete LaRoca’s (and, of course, Steve Swallow’s) energetic ‘inside/outside’ playing connects Bley to the emerging 60s jazz sound, especially the John Coltrane-McCoy Tyner-Elvin Jones sound, soon to be paradigmatic.

On his outing, Paul picks up some sticks and, boldly inserts himself in the fray. Revealingly, instead of typical drum solo vocabulary, he deconstructs some simple time-keeping patterns, as he’d often done with Evans. This is a key point: Paul’s so-called broken time enables his complete immersion in the Peacock-Bley chemistry.

Motian really impresses on this track; Bley and Peacock in 1963 are a different universe than Evans and LaFaro in 1961, and Motian just keeps being himself. It’s one thing to play some jagged, broken time with Evans and LaFaro on a beautiful reading of “Milestones”; it’s something else to do it on an abstract blues with two revolutionary virtuosos.

4.) Long Ago And Far Away (Jerome Kern)

The first chorus of the piano solo is the most balanced trio statement so far, with Motian fully involved in the improvisation and dialogue.

5.) Moor (Gary Peacock)

“Moor” is the only tune in the session without any chord changes to either abandon or reconstitute; the Peacock-Bley duologue is now perfectly aligned with the future, for this moody, minor-key piece is the “ECM sound” in embryonic form. Motian is perfectly sensitive to and supportive of Peacock’s wildly discursive solo.

Paul Bley in April 1963 was at an inflection point; his classic solo on “All The Things You Are” with Sonny Rollins was a few months ahead, Footloose! would be finished and released before the end of the year, and he would soon be a part of the Jazz Composer’s Guild. Peacock was in a similar place, with a bright future imminent; gigs and recordings with Bill Evans, Miles Davis, Albert Ayler, Tony Williams, and Lowell Davidson all occurred later in ‘63 and on into 1964.

In the wider frame, even bigger changes were just around the corner; the murder of JFK, the arrival of the Beatles, and the Civil Rights movement would soon change everything. Bley, Peacock, and Motian are ready. Each would explore the coming tumult in his own way; Bley with synthesizers and his own record label, Peacock with spiritual studies, a move to Japan, and a time away from music, while Motian stayed constant, as we’ll see.

The next album2 in our discussion is Paul’s final recording with the pianist that brought him to national attention.

BILL EVANS: TRIO 64 (VERVE, V6-8578)

Webster Hall, NYC, Wednesday, December 18th, 1963; Bill Evans, piano; Gary Peacock, bass; Paul Motian, drums. Produced by Creed Taylor. Released 1964.

For the first time, Motian is applying the vocabulary and aesthetic he was developing while playing free music with Bley, Peacock, and others to a straight ahead session. Overall, he is noticeably more radical, or more personal, on this session. It’s a bit paradoxical, but makes sense- when sitting in and checking it out with Bley and Peacock, he’s more inside; when he’s at home with his familiar boss Bill Evans, Paul plays more ‘out’.

Tellingly, Motian listed Trio 64 as a “great example of his playing” in a 1994 Modern Drummer feature.

By this time, the Bill Evans Trio was an established economic force in the jazz business, so it’s fitting that Trio 64 was produced by none other than Creed Taylor, a music business power broker and founder of both Impulse and CTI Records. A young Keith Jarrett heard this short-lived edition of the band in ’63 or ’64.

There is an occasionally disengaged quality to some of the tracks (“Dancing In The Dark”, “I’ll See You Again”) as well as some tempo and texture redundancy on the album. Rumors have circulated about extra-musical interference at this session. It’s said that Creed Taylor removed Motian’s toms from the session (which, if true, must have happened after they began recording, as they are clearly audible on “Little Lulu”, at least).

It’s possible that Evans’ addiction was negatively effecting the proceedings. The rehearsal take of “My Heart Stood Still”, available on a 1999 reissue, has a moment of conversation between Gary and Bill, with Bill sounding unenthused at best.

It was less than a month since the Kennedy assassination when Trio 64 was recorded. I don’t hear any explicit connection between the music of Trio 64 and the death of Kennedy, but some of the feeling of daily life in December 1963 must be on this recording. Is the tense atmosphere on some of these tracks a taste of the tense, post-assassination vibe on the street?

Regardless, it’s a beloved album, a personal favorite of mine, and should be studied since it’s the only official release of Gary Peacock (a soon-to-be 60’s radical) and Bill Evans (emblematic of the 50’s) together, and the last recording of Bill Evans with Paul Motian.

This is also the final moment when Paul Motian was simply an excellent jazz drummer making a jazz piano trio record. After this he was…something else.

1.) Little Lulu (Buddy Kaye, Sidney Lippman, Fred Wise) Paul’s rhythmic unison with Evans in the second bar of Evans’ solo clearly announces Motian’s evolving conception; no longer ‘merely’ keeping time, he would now create rhythmic and textural counterpoint to the solo, while maintaining an overall swing feel; the phrase ‘broken time’ sums it up.

Generally, on this session, it seems that Peacock and Motian are conceptually aligned; Evans might be occasionally left out to dry.

2.) A Sleepin’ Bee (Truman Capote, Harold Arlen) Motian’s broken time concept is in full relief- he never commits to a recurring cymbal pattern, and moves freely between half-note and quarter-note based patterns.

3.) Always (Irving Berlin) A waltz, and some fascinating details from Mr. Motian: broken triplets a la Elvin Jones, loud bass drum on beat 1, dead strokes on the cymbal to break up the time, and at one point a buzz roll on the snare drum for three beats. Is the lovely Berlin melody is well-served by such willful abstraction? Again, there seems to be tension in the studio.

4.) Santa Claus Is Coming To Town (John Coots, Haven Gillespie). The fastest tune on this session. Peacock walks 4/4 after the head, and the trio settles down and works up a head of steam. It’s a relief to hear (almost) straight 4/4 and two (almost) relaxed piano choruses after the unsettled “Sleepin’ Bee” and “Always”.

5.) I’ll See You Again (Noel Coward) Back to our bumpy 3/4. Paul plays many of the same ideas as he did on “Always”, though here a bit more subdued.

6.) For Heaven’s Sake (Don Meyer, Elise Bretton, Sherman Edwards) Finally, a ballad. The jittery, broken-time concept simmers down, and Motian plays what would later become some of his trademark ballad vocabulary: occasional experimental cymbal rolls, hi hat and bass drum accents, unadorned left hand brush sweeps, and freely switching back and forth between ballad tempo and double time. Paul’s mature conception is stepping into the light.

7.) Dancing In The Dark (Dietz-Schwarz) Evans goes for some big double-time phrases right out of the melody, but do Motian and Peacock have other concerns? We get a touch of 4/4 again in the 2nd piano chorus, but the final melody is barely stated, and the ending has a feeling of “ok, that’s enough”.

8.) Everything Happens To Me (Thomas Adair, Matt Dennis) The trio achieves a more unified group sound here than on any other track. Paul and Gary’s relentless experimenting seem more matched to Evans’ masterful reading of the melody; there is concentrated feeling and expressiveness from all players; and Paul is leaving more space in his playing. Save a few details (the triplets with his feet in the second A of Bill’s second chorus), this could be Paul Motian circa 1990 or 2000. It’s the most perspicacious of the eight tracks on the album, in terms of Paul’s playing.

It’s poignant, for me, to realize that this was the end for Evans and Motian. It’s the last track on the last album they ever made. Six months after this session Paul left Bill Evans’ group, quitting the trio in the middle of an engagement at Shelly’s Manne-Hole in Los Angeles and returning to New York out of a job.

“It [playing with Bill Evans] got to a point where it didn’t seem like it was me anymore. I didn’t seem part of it. I wanted to go in other directions because there was a lot of music happening in New York at that time.”

-Paul Motian, quoted by Scott K. Fish, Modern Drummer, April-May 1980.

“I quit Evans in ’64 because the music started to get wishy-washy. It turned into piano-bar music. I just couldn’t dig it anymore. I was playing too soft, I never played with sticks. I just hated that shit.”

-Paul Motian, quoted by Ken Micallef, Modern Drummer, June 1994.

It’s possible to see how Motian might have perceived Bill Evans’ music as being out of step with the changes taking place in music and society in 1964. Those must have been heady times indeed. Paul Motian was a man on a mission, determined to grow, serious about changing his music.

In the next installment, I’ll take a very deep dive into Paul Bley’s Turning Point, and discuss how Motian took it all apart, fully immersing himself in the new jazz of the 1960s. And we’ll finish with a listen to Mose Allison’s Wild Man On The Loose, where, fittingly Mr. Paul Motian almost puts it all back together.

Footloose! was unfinished at the time Bley/Peacock/Motian recorded their version of “When Will The Blues Leave?”, so I don’t know to what extent, if any, Motian was aware of LaRoca with Bley. My hunch is that Paul Motian more-or-less knew what LaRoca was all about, and vice versa.

For Motian completists, there is the excellent Newport ’63 on Columbia by pianist Martial Solal, which documents Solal’s appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival, with Motian and bassist Teddy Kotick. Solal’s music is challenging and progressive, and even features Paul playing a Max Roach tempo in a section of a multi-part suite. However, since this album features Paul as the consummate sideman, playing Solal’s music beautifully, we’ll pass it over for our discussion.

You’re right, I want to hear these two records as soon as possible. Well done.

Great stuff, Vinnie! Looking forward to reading more.