Billy Hart is a world treasure. One of our most important drummers and an active link to 20th century jazz, Billy is a vital, still-developing musician at the top of his game. Everything Hart shares comes from his imagination and experience, but has deep roots in the collective wisdom of his community.

He plays the truth. He embodies individuality within community. He is so much fun to hear.

Billy Hart will turn 83 on November 29th. I’m celebrating his birthday this year by listening to his first five solo albums:

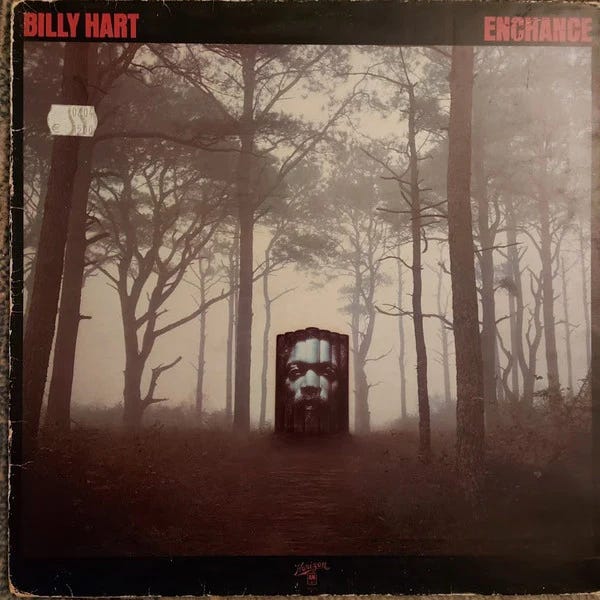

Enchance (Horizon, 1977)

Oshumare (Gramavision, 1985)

Rah (Gramavision, 1988)

Amethyst (Arabesque, 1993)

Oceans of Time (Arabesque, 1996)

I’ll write about Enchance, Oshumare, and Rah below, and will do another piece on Amethyst and Oceans of Time. Both of those are streaming, but the Horizon and Gramavision dates seem to be only available as vinyl rips on YouTube.

All five records feature surprising combinations of players, it’s one of their main attractions. We have Dewey Redman with Don Pullen (Enchance), Steve Coleman and Branford Marsalis with Bill Frisell (Oshumare); Eddie Henderson, Buster Williams and Billy (half of Mwandishi) with Kenny Kirkland, Kevin Eubanks, and Bill Frisell (Rah), Mark Feldman with John Stubblefield, Dave Fiuczynski, and Dave Kikoski (Amethyst and Oceans of Time) Then, as now, NYC musicians do not respect genre and scene segregation. Everyone plays with everyone, at least once. But the real story is the development of Hart’s conception as a bandleader.

Hart’s professional life began as the drummer in Wes Montgomery’s band; the few snapshots of Hart in 1963 with Montgomery show how little space he was given to express anything besides the tempo of the song, good as the music is.

But on these records, under his own name, recorded after Billy was a part of Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi, we can hear Billy coming ever more into his own, not just as a player, but as a conceptualist.

In Billy’s world, contrasting sounds and styles sit together comfortably and become blended: a romantic violin solos over a heavy R&B beat; an intense, out-of-time melody becomes heavy 4/4 swing; distorted guitar follows on the heels of Bill Evans-style piano trio; and so on.

Such mash-ups have always been a part American culture, and are a major part of what makes jazz jazz: Lonnie Johnson recorded blues guitar solos with Louis Armstrong in 1927, after all. On Billy’s records, the mash-ups have a casual, unassuming feel to them. This might be an extension of Billy’s vibe as a drummer, his easy, unshowy brilliance.

As I listened, a cumulative effect occurred, and Billy Hart emerges not just as a master jazz drummer but as a visionary bandleader. Just about every way to play in the late 20th century is represented, or at least nodded at, on these discs.

Here’s an incomplete list of the players on Billy’s albums: Oliver Lake, Dewey Redman, Don Pullen, Dave Holland, Dave Liebman, Kenny Kirkland, Steve Coleman, Branford Marsalis, Kevin Eubanks, Bill Frisell, Didier Lockwood, Buster Williams, David Fiuczynski, John Stubblefield, Mark Feldman, Chris Potter. That’s a lot of opinions.

Billy’s mastery can be understood just in that list of players. Hart can get everyone— regardless of background, age, or scene— playing together. He’ll make the musicians sound like a band, and knock the listener’s socks off. Three cheers for Billy Hart!

Mashups, juxtaposition and collage are part of American culture, modern life, and are basic flavors in jazz. It’s his use of juxtaposition and collage, which he commands as well as a drumset, that meaningfully connects Billy Hart, born in 1940, to the masters born in the Sixties and Seventies—Terri Lyne Carrington, Gerald Cleaver, Jim Black, Brian Blade, Johnathan Blake, and many others.

Billy Hart: Enchance (Horizon, recorded and released 1977)

Billy Hart wants to be playing the newest stuff with the hottest players. This is true in 2023, and it was true in 1977.

In 1977, the newest stuff meant bebop on the Miles-Coltrane continuum, experimentalism from the Black Artists Group (St. Louis) or the AACM (Chicago); and something from Ornette Coleman. On Enchance, Hart has Buster Williams, Dave Holland, Marvin Hannibal Peterson, and Eddie Henderson on the Miles-Coltrane line, Dewey Redman from Ornette Coleman’s world, and Oliver Lake from the Black Artists Group.

Pianist Don Pullen, a major part of the jazz world of the Seventies and Eighties, might be the defining sound of Enchance. When I asked Billy about Don Pullen and Enchance, Hart told me that he wanted Cecil Taylor for the date, but when he couldn’t get him, Pullen was the only logical choice.

For Hart’s own invaluable comments on Enchance, see this excerpt from his memoir that he and Ethan Iverson have been working on right here.

“Diff Customs” (Oliver Lake). A sort of thesis statement for the session as a whole, Billy Hart and Buster Williams graft Lake’s start-and-stop melody to the deepest swing, moving between multi-directional rhythm and heavy 4/4. Something about the Booker Little-Eric Dolphy sound suggested AACM/BAG experimentalism, and here, that experimentalism co-exists with tough Seventies jazz.

“Shadow Dance” (Holland). One of the highlights of Enchance is hearing the bluesy free improvising of Oliver Lake, Dewey Redman, and Don Pullen with Dave Holland and Billy Hart. Lake plays against the undercurrent, Dewey luxuriates in the 12/8, and Pullen burns over some 4/4, moving in and out of time. This track could have been 30 minutes, we’d all love it.

“Layla-Joy” (Billy Hart). This is Hart’s first-ever composition, a tender evocation of his newborn daughter, with Buster Williams and Michael Carvin on hand to help him celebrate. It’s a simple, vulnerable melody, made even more so by the direct, unaffected way these masters play it.

“Corner Culture” (Redman). When Billy fills between the melody phrases, he’s playing Tony Williams’ vocabulary, but Billy’s so personal that any question of imitating Tony is moot. The liner notes to Enchance contain a long essay by Redman explaining the piece: Redman means to evoke the entire African-American street experience in one tune. Dewey is an underrated composer, and kudos to Hart for including a Redman tune.

“Rahsaan Is Beautiful” (Peterson). The electric piano (was this played by producer/keyboardist Mark Grey?) in an acoustic group and meditative vibe suggest Hancock’s Mwandishi, Bennie Maupin’s The Jewel and The Lotus, Horacee Arnold’s Tribe, and doubtless many more, a totally contemporary sound at the time. No solos, just a few decorations around the melody, leading perfectly into:

“Pharoah” (Pullen). After the declamatory melody, Dewey Redman solos for the ages with the Pullen/ Holland/Hart rhythm section. Billy never abandons tempo, nor does he state a pulse. When Pullen takes over, he at first avoids his Cecil whirlwind for more Redman-esque melodies. The final Hannibal Peterson-Billy Hart duo is an avant-garde parade.

“Hymn For The Old Year” (Lake). Experimental music should (and usually does) lead to new music, and here is that music. Lake’s melody just unfurls, slowly and calmly while occasionally spinning out, as the rhythm section goes its own way. Eventually, Billy goes for the multi-directional Rashied Ali/Milford Graves texture wholeheartedly.

Enchance was praised by some critics, and certainly altered the jazz public’s perception of Billy Hart. Hart took the label’s lack of interest in a follow-up in stride, though it would be a few years before he recorded as a leader again.

Billy Hart: Oshumare (Gramavision, recorded and released in 1985)

Gramavision was run by real estate magnate and city planner Jonathan Rose. It was an important label at the time, releasing albums by John Scofield, clarinetist/composer John Carter, and John Blake Jr., and a few important releases by James Newton and Kronos Quartet. James Newton was the one who brought Hart to the label, and Billy's music is right at home on Gramavision.

Oshumare is the Yoruba-Santeria orisha associated with rainbows; an apt choice for an album with every color in the modern jazz spectrum. Enchance was a collaboration across scenes by seasoned professionals, while Oshumare, Billy’s second leader date, finds Billy closer to the Art Blakey mold, hiring the best young players in town: Steve Coleman, Kevin Eubanks, Bill Frisell, Kenny Kirkland, and Branford Marsalis.

In 1985, Billy Hart is the wise older brother, the one who can get everyone on the same page. Coleman, Kirkland, Eubanks, Frisell, and Marsalis are all at their best and heard in a slightly different context than usual. Hart’s own comments to Ethan Iverson on both Oshumare and Rah are essential and are found here.

“Duchess” (Billy Hart). Written in memory of Hart’s grandmother, who bought him his first drum, this is a well-known Billy melody, played often by the Billy Hart Quartet in a medium 4/4. Here, it’s a straight-eighth fantasy for a synth solo by Mark Grey, who helped Billy arrange the tune for the session. Kirkland and Branford both solo, and it’s great to hear them play this kind of tune, far from the usual fare of the Wynton Marsalis Quintet in 1985.

“Waiting Inside” (Bill Frisell). Frisell’s tune starts out-of-time, but gradually a tempo emerges for a Steve Coleman solo. According to Lord Discography, this is one of only two recordings of Frisell with Steve Coleman. It’s special to hear the two visionaries share the space and easily make some great music together.

“Chance” (Kenny Kirkland). This is a beautiful dark waltz, a setting for solos by the strings: Frisell, violinist Didier Lockwood, and Dave Holland. On the LP, this is the end of Side 1. The net effect is powerful: this is advanced music touching on many scenes. Billy Hart is bringing us together.

“Lorca” (Billy Hart). Billy’s big-as-life Latin groove and the simple chanting melody evoke the spirit of his son Lorca Hart, a great drummer based in California.

“Cosmosis” (Dave Holland). On Enchance, Holland contributed a strong swinger for Dewey Redman and Don Pullen. Here he does the same for Kenny Kirkland and Branford. The searing 4/4 allows for some Billy Hart fireworks, but the real magic is in his cymbal beat. Kenny Kirkland with Branford Marsalis makes Oshumare Young Lion-adjacent, but as Billy stated, he thought of Kirkland as a romantic player at the time.

“IDGAF Suite” (Kevin Eubanks). I wonder what IDGAF refers to1. The presence of Eubanks, Coleman, and Holland makes Oshumare a companion record to Holland’s ECM records featuring Marvin “Smitty” Smith— Seeds of Time, Razor’s Edge, Triplicate, and Extensions. Dave Holland, Bill Frisell, Steve Coleman, Branford Marsalis: Oshumare is one-stop shopping for the best of Eighties jazz.

“May Dance” (Dave Holland). Another highlight, this cut has that club feel, a hot band in the middle of a set. Billy’s cymbal behind Holland is the truth.

“Mad Monkey” (Steve Coleman). Coleman’s tune is idiomatic Coleman: a syncopated and peculiar 5/4 bass line; interlocking rhythm parts by Kirkland, Holland, and Eubanks; and a rhythm-oriented melodic line, played by Branford and Coleman. To Hart, however, Coleman’s tune is a playground. Billy runs up and down the slide, grabs the monkey bars, is unafraid of the 5/4, and follows his own path throughout the piece, a wild, irreverent close to a classic record.

Billy Hart: Rah (Gramavision, recorded 1987, released 1988)

Hart’s second Gramavision record was supposed to feature the same cast as Oshumare, but some last minute changes brought Dave Liebman and Eddie Henderson on board. More on Billy’s connection to Liebman and Eddie Henderson below.

“Motional” (Billy Hart). Kirkland, backed by Hart with Eddie Gomez, is astonishing on this medium-up burner. Only Billy Hart was programming a Bill Frisell solo on the heels of Kenny Kirkland in 1987, then wrapping up the whole thing with a synth solo by Mark Grey.

“Reflections” (Kevin Eubanks). In 1987, Hart was working with Liebman, pianist Richie Bierach, and bassist Ron McClure in Quest, a group that sought a connection between early 20th century composers like Berg, Schoenberg, and Bartok and the legacy of the Coltrane quartet.

From 1970 to 1973, Billy was a member of Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi, with Buster Williams on bass, trumpeter Eddie Henderson, Bennie Maupin on woodwinds, and trombonist Julian Preister. Among the most innovative groups of the Seventies, Mwandishi ended in 1973 when Hancock turned his focus to more literal funk and R&B explorations.

On Rah, Hart represents Mwandishi with Buster Williams and Eddie Henderson, and is nodding towards Quest by including Liebman, a snapshot of two disparate worlds coexisting, almost two bands at once. That’s one of the hooks of the record.

On “Reflections”, Hart is in his quasi-Brazilian zone, riding the waves with Liebman and Henderson, and burning with Eubanks. The Hart effect is coming into focus.

“Naaj” (Billy Hart). The groove and tempo is almost the same as “Reflections”. Billy bashes and crashes with Frisell before handing it off to Liebman and Ralph Moore for more fun. Hart changes the energy and focus just slightly for each soloist throughout.

“Breakup” (Frisell). Following the tuneful, sunny “Naaj” with Frisell’s “Breakup” demonstrates Hart’s sensibility. Frisell’s abstract theme frames several short and fascinating Billy Hart drum solos: Billy goes for some Buddy Rich/Tony Williams snare fireworks and round-the-toms fusion gestures, even a rock and roll rave up. Hart is on Joey Baron’s turf here, and he sounds right at home.

“Reneda” (Billy Hart). The semi-Brazilian beat undergirds a Hart melody celebrating his nieces Ronda and Renee. Billy is the continuity in the wide-ranging solos from Buster Williams, Kirkland at his most melodic and forceful, and Liebman.

“Reminder” (Frisell) Gomez and Hart team up to provide the just-right quasi-noir texture, setting up Kevin Eubanks’ echt Eighties solo, complete with whammy bar dive bombs, which ends leads in a romantic Kirkland solo, as though Jeff Beck were opening for Bill Evans.

“Dreams” (Henderson). Williams opening solo on the most Mwandishi-like tune on the date sets the mood. After the head, the medium tempo 3/4 is used for solos from Henderson, Moore, and Eubanks, all sounding as if they are dreaming a dream of Mwandishi.

“Jungu” (Liebman). Pieces like “Jungu”— a slow almost-swinging 3/4 with complex harmony— were at the core of Quest’s repertoire. But this is a Billy Hart record, so after Liebman’s solo, we get a soulful, bluesy Frisell solo over the complex harmony. Bringing Frisell in to clean up seems obvious now, but it couldn’t have seemed so in 1987.

COMING SOON: Deep dive into Amethyst and Oceans of Time, Hart’s Nineties records, where the collage aesthetic of his previous releases is taken even further.

It stands for I don’t give a f—. Thank you Dan!

IDGAF as in "I don't give a f@#*"

What a great way to begin a new day...reading about and listening to Billy Hart!! Thanks so much Vinnie!