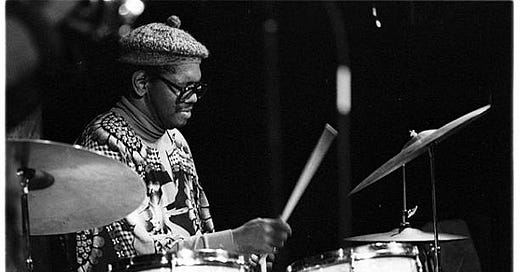

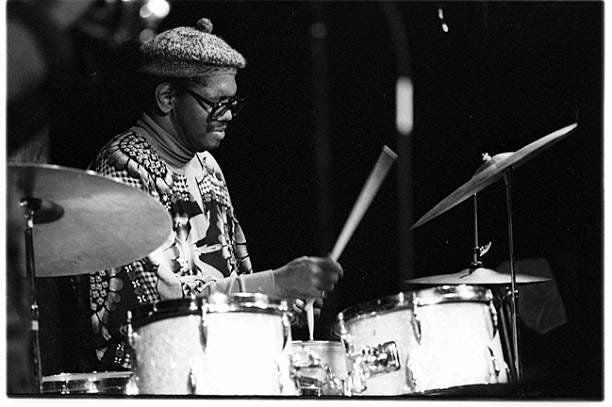

Drummer Edward Blackwell, who died in 1992, was born on October 10, 1929; he would have turned 94 years old today. Blackwell was a New Orleans native who left a deep imprint on everyone he encountered, starting in his home city.

Pianist Ellis Marsalis, father of Wynton, Branford, Delfeayo, and Jason, was among the first to be affected by Blackwell:

I was from the school where drummers played a solo and when they got to the end of it they went ‘yata-tat-tat-tata-ta-boom!’ and everybody came back in.

I didn’t know anything about choruses and the Max Roach style of drumming was still something that I had not really been able to tune into with an analytical ear. Edward would play drum solos and all his drum solos were constructed for the form that we were playing in. Edward would say ‘Like, I’m gonna play 2 choruses’ or what have you, and he would play that. And there were no mistakes about it, he was right there.

It was up to the other musicians in the band to be able to hear the drums, the language of the drum. And sometimes we’d lock up on it and sometimes we wouldn’t.

So one day he got very angry and stopped in the middle of the song. He smashed down on the cymbal and said ‘Man, what’s the matter with you guys? Can’t you hear anything?’ He said, ‘Look, when I play the head I’m going to play with this cymbal. I’m going to play the bridge with this cymbal, and I’m going to go back to the head and play with this cymbal. And when I play a solo, listen to what I’m playing. And when I get to the end, you should be able to hear what I’m doing.

And it was then that I also started to be aware of Max Roach, because we would play records and Edward would say ‘Listen, I want you to listen to what Max is doing right here’ and he’d sing along with Max. And I had begun to hear drum phrases in the same way that I would hear horn or melodic phrases and it was a kind of melodicism that existed in Edward’s playing that also existed in Max’s playing

(Wilmer. “Alvin Batiste and Ellis Marsalis.” p. 9).

New Orleans R&B drummer John Boudreaux was another:

Blackwell played a bigger inspiration on me, I’d say, than any drummer I heard, cause he was playin’ so different and correct. He just exaggerated correctness and precision...

(Battiste. Liner notes from “New Orleans Heritage Jazz.” p.12).

Blackwell left New Orleans for Los Angeles in 1951, where, two years later, he connected with alto saxophonist and composer Ornette Coleman, whom he’d briefly met in New Orleans in 1949. Coleman was a total unknown at the time, his playing and compositions deemed too radical by most musicians.

Of course, by the end of the Fifties, Coleman and his quartet were the most influential and controversial new sound in jazz. At the time of Coleman’s death in 2015, he was a beloved elder statesman whose music was rightly heard as among the most important of the 20th and 21st centuries. But that’s another story.

Back to LA in 1953: According to Blackwell, he and Coleman roomed together, even sharing a double bed, while they held down jobs at department stores. In their off hours, they rehearsed Coleman’s new tunes, listened to records, and talked about music.

In 1955, Blackwell returned to New Orleans. He was based1 there when he joined Ray Charles in 19572 and remained until June 1960, when he left for NYC to join Ornette’s band at the Five Spot, taking over for Billy Higgins.

So, what was Blackwell up to from 1955 to 1960?

According to David Schmalenberger’s masterful and invaluable paper about Blackwell available on the PAS website, a major source for this essay, Blackwell, back in New Orleans, went to work around town. He gigged with now-legendary R&B musicians including Roy Brown (composer of “Good Rockin’ Tonight”), Earl King (on whose arrangement of “Let The Good Times Roll” Jimi Hendrix based his own version in 1968), and Huey “Piano” Smith (who had a hit with “Rockin’ Pneumonia and The Boogie Woogie Flu”).

All of this music can seem, to our ears, quite distant from Ornette Coleman, but if we remember Dewey Redman’s comment that free jazz really came from the blues, perhaps Roy Brown, Earl King, and Huey “Piano” Smith aren’t so far from Ornette after all.

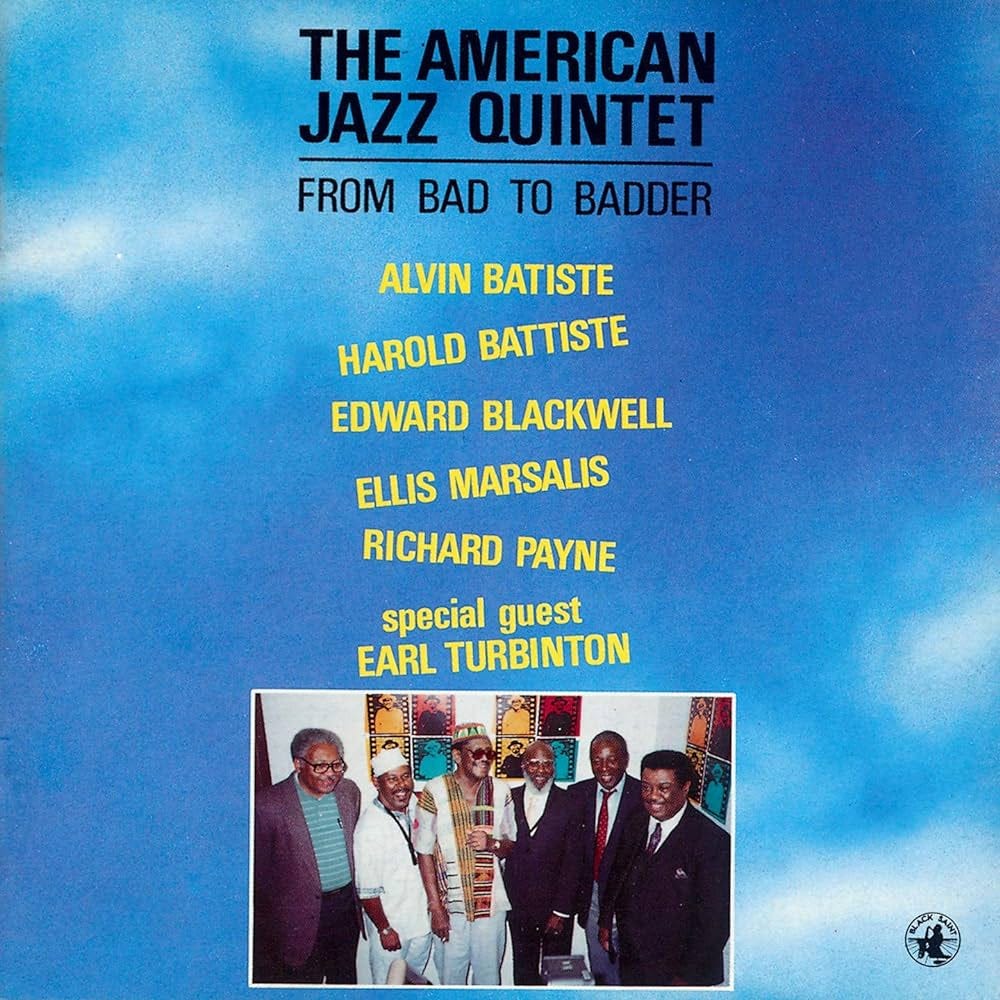

In addition to blues and R&B gigs, around this time Blackwell also began playing with tenor saxophonist Harold Battiste, with whom he formed the American Jazz Quintet3.

Consisting of Dr. Alvin Batiste on clarinet and Harold Battiste4 on tenor saxophone, with a rhythm section of pianist Ellis Marsalis, various bassists including Richard Payne, William Swanson, and Otis DuVernay, and Blackwell, the American Jazz Quintet was the most dedicated bebop-focussed group to emerge in New Orleans in the Fifties.

As Battiste and Marsalis made clear, modern jazz had no presence in the marketplace of their home city at the time. The American Jazz Quintet’s existence was a statement of artistry and self-determination. Seen in this light, the AJQ, like the R&B and blues singers Blackwell was gigging with, have much in common with Ornette Coleman.

Unbelievably, all five American Jazz Quintet albums are streaming on Apple Music. Taken together they shed light on:

How Blackwell sounded at the beginning of his career. The American Jazz Quintet session released as In The Beginning, from 1956, is Blackwell’s earliest known recording.

The efforts of musicians to control their destiny in the marketplace. This is the same impulse that led to the founding of the AACM, the Black Artists’ Group, the Detroit Artists Workshop, the Jazz Composer’s Guild, and so on.

How ideas spread before the advent of jazz education. These musicians learned this stuff completely on their own, with little or no contact with Miles, Monk, Coltrane, etc, and without the Aebersold-inspired transcription industry of today. They got the records, learned the music, and went to work. Amazing. Bravo, American Jazz Quintet!

Ed Blackwell’s musical goals before joining the Ornette Coleman quartet. With the American Jazz Quintet, 32-bar and 12-bar forms and the like reign supreme, and Blackwell is a cutting edge modernist strictly in the Max Roach tradition.

Blackwell’s place within his hometown jazz community. On these records, we can sense the esteem, in both the frequent solos and the authority in his time feel, in which Blackwell was held by his peers. He was their advanced super-drummer, maybe even the essential member of the band. The picture below might say it all:

Here’s a list of the American Jazz Quintet’s albums. All recordings took place at Cosimo Mattassa’s studio in New Orleans except where noted.

In The Beginning (AFO, recorded 1956, released in 1991)

Boogie Live 1958 (AFO, recorded 1958, released in 1994)

Gulf Coast Jazz Vol. 1 (VSOP, recorded and released in 1959)

Gulf Coast Jazz: Wade In The Water (VSOP, recorded in 1959)

From Bad To Badder (Soul Note, recorded in Atlanta, GA in 1987, released 1989)

The first two, In The Beginning and Boogie Live 1958, are more-or-less historical interest recordings, though not without some magical moments. Both albums called Gulf Coast Jazz are more finished, while From Bad To Badder is a live reunion album.

In The Beginning, from 1956, is the earliest recording of Blackwell listed in the Lord Discography. Here Blackwell is playing a homemade drumset, one he assembled himself out of converted marching drums, with a 16” bass drum and 9x13 floor tom. He uses this thuddy and singing little kit to great effect on “Nigeria”, a blues with a New Orleans/Cuban feel, and opens up for some telling solos on “Carrie Mae” and “Ohadi”. The band is great, with standout solos from both Battistes, while Ellis Marsalis and Blackwell seem to share a special chemistry.

Recorded at Booker T. Washington High School in New Orleans, Boogie Live 1958 is a home recording with a mic right next to the drums, giving us a chance to really hear Blackwell. Tenor saxophonist Nat Perrilliatt (subbing for Harold Battiste) and Dr. Alvin Batiste sound wonderful, but my interest is in Blackwell and Marsalis. They’ve figured out momentum and communication, though they’re still working out some kinks. The high point for me is “Fourth Month”, with Marsalis’s gorgeous intro, Dr. Battiste’s easy way with the audience, and the long, edgy Blackwell performance that follows. That driving, way-uptempo beat Blackwell frequently deployed with Coleman is right here.

Gulf Coast Jazz Vol. 1 was recorded in 1959. All twelve compositions are by band members, the performances are brief, to the point, and beautifully played. “Stephanie” features a strong, swinging, on-the-form Blackwell with brushes, a true rarity. “Nevermore”, heard on both Boogie Live and In The Beginning, is taken faster, which is better. On the second half of the head, Blackwell plays dotted eighth notes in his feet, exactly like a drummer today might. Here is our Blackwell. “Apartment 11” is another heavy swinger, a sample of how Blackwell might have played with Ray Charles.

Confusingly, both Gulf Coast Jazz albums have the same cover, but totally different music.

Gulf Coast Jazz: Wade In The Water. Perhaps recorded at the same sessions as the previous release, this record contains a few traditional tunes mixed in with the groups originals. There’s much of interest here: Blackwell’s up-to-the-minute double time on “Wade In The Water”, his solo breaks and tempo on “When The Saints Go Marching In”. On “Sinner Don’t Let This Harvest Pass”, we have an early example of Blackwell in Afro-Cuban 12/8. This must be one of the earliest examples of this in jazz.

From Bad To Badder. In Atlanta, in 1987, an Ed Blackwell Festival was held, and the American Jazz Quintet re-united. It’s a joy to hear Blackwell stretch out with his homies on “Edith”, a lengthy blues, and to hear the camaraderie and reverence on “To Brownie” (mistitled, the tune is actually “Nevermore”).

“Tony” is a trio of Marsalis, Alvin Batiste, and Blackwell, clarinet, piano, and drums, a classic combination going back to the Nineteen Twenties. Midway through, Blackwell and Marsalis share a powerful and memorable duo. Marsalis’ beautiful sound and serious intent merge perfectly with Blackwell’s suggestions of double and then quadruple time.

It’s a privilege to hear such an intimate exchange. Are they reminiscing about the old days? Or are they suggesting the future?

Save a summer-long L.A. return trip in 1956, where Blackwell was accompanied by Ellis Marsalis and Harold Battiste. This is evidently when Ellis Marsalis played with Ornette Coleman, which I know Wynton has talked about somewhere, but I can’t find right now. Readers, chime in!

There are no recordings of Blackwell with Ray Charles that I know of. Maybe one day a radio broadcast or local TV spot will surface, if it hasn’t already.

Battiste is an important figure. In addition to being a wonderful player and educator, and later, a major part of the LA studio scene, he founded an organization called AFO (“All For One”) in New Orleans in 1961. AFO was, evidently, a musicians’ collective intended to both disseminate modern jazz (which had virtually no presence in New Orleans) and to turn musicians from employees to stakeholders in the city’s growing record business.

These two Batistes might be related, and might be related to Jon Batiste, but I can’t say for sure.

Excellent dive into Mr. Blackwell's life and music. I remember driving over High Street by the campus of Wesleyan University where the drummer settled late in life and see him off for his walk. I thought "What a wonderful place to live with Ed Blackwell in the community!"

As much Blackwell as I've listened to, I've never checked out the American Jazz Quintet. Thanks Vinnie!