For Frederick Waits

Little Stevie Wonder, McCoy Tyner, Soul!, Jazzmobile, M'Boom, Mulgrew Miller.....

Freddie Waits is one of the most important drummers in jazz. Besides sounding great and contributing to dozens of classic records, Waits, in his career and in his playing, was a connector between modern jazz, soul/funk/R&B, and the avant-garde, with an ear always bent toward the world’s great percussion traditions.

In my twenties, I was attracted to his unconventional, atypical sound: clear, high-pitched cymbals, a snare drum tuned high and tight, low and thuddy bass drum. His vocabulary was distinct and personal, sort of split between Fifties hard-bop expertise and the beyond of the Sixties and Seventies.

To do Mr. Waits justice, he should have a huge, sprawling essay that traces his complete biography and career, winding its way through the Great Migration, Black music education, Black show business, Motown, Detroit jazz, Black entrepreneurship, new media, drummers as an outsider group within the music community, self-determination, and fatherhood.

Instead, I’ve got some context, chronology, musical highlights, and a few reflections. Gratitude and respect for Freddie Waits.

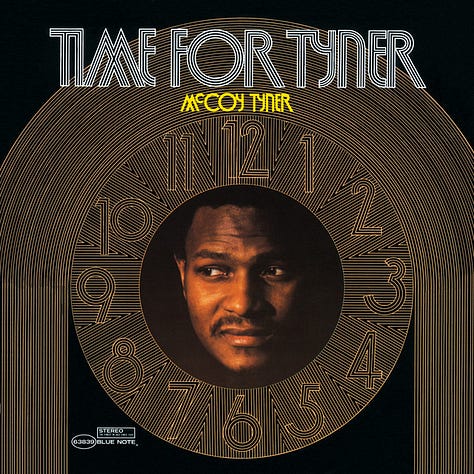

Playing drums on McCoy Tyner’s Time For Tyner, Gary Bartz’ Another Earth, and Bennie Maupin’s The Jewel In The Lotus is enough to make Waits historically important, but, as always, there was more. Much of what Waits’s career was uncommon at the time, but is de rigueur today.

Waits was an early proponent of jazz education and a dedicated teacher, first as a drummer in NYC’s city-and-state-funded Jazzmobile in 1968, later as a clinician. By the late 80’s Waits was teaching at the New School. Here’s a link to some Afro-Cuban bell patterns on Todd Bishop’s Cruise Ship Drummer site, courtesy of Freddie Waits.

Waits worked in new media and new technology. For a time, Mr. Waits was a musical director and contractor for the TV show Soul!, a New York City-made, nationally distributed PBS show. Soul! was hugely popular, featuring all Black artists in front of an all-Black audience. Waits often played with the featured artists, and here’s a link to Waits playing “Let’s Stay Together” with Mr. Al Green (fast forward to 49:15).

Waits was a trained percussionist and an accomplished mallet player. Waits’ marimba is prominent and happening with Bennie Maupin on The Jewel In The Lotus, and with M’Boom, the percussion ensemble founded by Max Roach in 1970.

Frederick Douglas Waits was born April 27, 1940, in Jackson, Mississippi, a thriving city of nearly 100,000. He discovered the drums in childhood, and by high school was listening to Dizzy, Miles, Bird, and Max. Some of his first professional experiences were with with master bluesmen John Lee Hooker, Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller), and others.

A crucial quote:

“I went to see B.B. King in Jackson, and he lectured to us young players…Do you know what he lectured on? Bird! B.B. King said “Listen to Bird!” I’ve never forgotten that….When I was playing the blues, I separated jazz and blues in my mind. I didn’t realize they were really the same element.” 1

After high school, a family connection brought Waits to Detroit. Soon after arriving, he landed his first steady touring gig with R&B legend Little Willie John2. Bennie Maupin introduced Waits to the wider Detroit jazz community, starting a chain of connections which brought Waits to the attention of producer Norman Whitfield. It was Whitfield who gave Waits his beginning at Motown Records.

At Motown, Waits recorded backing tracks and was popular with the stable of stars at the label. Berry Gordy, the head of Motown, urged him to join a Motown Revue touring package in the early spring of 1963, featuring Martha And The Vandellas, Smokey Robinson, and a novelty act, “Little” Stevie Wonder, a child star who played bongos, piano, and sang.

Freddie Waits is the drummer on “Fingertips, pt. 2”, the first hit single by Stevie Wonder3 , recorded on the Motown Revue tour that spring.

As Waits recalled in 1990,

"We recorded that the first week out on tour in Chicago. We opened on Tuesday, and recorded on Wednesday. When the tour reached New York five weeks later, the record was number one in the country....the Apollo was bombarded. It was like the experience you've seen of the Beatles. I saw one of the anniversary films and realized it was me playing. I didn't know it was filmed!" 4

Waits played on another epochal Motown smash, Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing In The Street”. In an article by Marc Myers for the Wall Street Journal found on writer Scott K. Fish’s website, Motown arranger Paul Riser credits Waits on the song, even though other sources list other drummers.

For me, it’s Freddie’s relentless and exciting backbeat that sets the track apart. “Dancing In The Street” was also a keen influence on the British rock bands— both the Kinks and the Who have versions of the song. Certainly, Waits heard the future— on “Dancing In The Street”, the snare drum is almost louder than the vocal.

In late 1963 and early 1964, jazz was moving forward, as always, and Waits was too. He started connecting with the NYC jazz scene, touring and recording with Paul Winter (Jazz Meets The Folk Song, Columbia, 1964), and Denny Zeitlin (Cathexis, Columbia, 1964).

Waits, teamed with Cecil McBee on both records, at the beginning of his recorded history, is distinctive. On “Repeat”, a Zeitlin composition on both Winter’s and Zeitlin’s records, his time feel is energetic and confident, his signature sound is present. Waits respects musical conventions, but has no need to pledge allegiance to them.

Other players were developing in parallel, and the next phase of Mr. Waits’ recorded output demonstrates his connection to his contemporaries. Collectively, this group—Waits, Joe Chambers, Billy Hart, Bobby Hutcherson, Stanley Cowell, Charles Tolliver, Gary Bartz, and others— were looking for a connection between the bebop tradition, contemporary Black pop, and the new sounds from jazz’s avant-garde.

Waits was the perfect drummer for this project, uniquely able to connect those dots and sing in his own voice.

Waits is on half of Freddie Hubbard’s High Blues Pressure (Atlantic, 1968) playing echt soul-jazz drums on Weldon Irvine’s “Can’t Let Her Go” and a truly mean shuffle on “High Blues Pressure”. The lo-fi, high-content Fastball (Label M, released 2001) with Waits, Herbie Lewis, Kenny Barron, and Bennie Maupin, recorded at the Left Bank in Baltimore in 1967, is a glimpse of Hubbard’s group in full flight.

McCoy Tyner’s Time For Tyner (Blue Note, 1968) (one of my favorites) is inconceivable without Waits. On “African Village”, Waits feeds the fire, gets loud and raucous, yet remains light; the texture remains open. There’s always room for Tyner and Hutcherson’s ideas to breathe. On “Surrey With The Fringe On Top”, Waits’ plays 3/4 on the ride cymbal almost non-stop; the 3/4 rubs against the tune’s driving 4/4 and allows McCoy to get his message over. This is selfless mastery.

Cementing Waits’ stature as one of the brightest minds in jazz are Gary Bartz’ Another Earth (Milestone, 1969), advanced music with an incredible band (Bartz, Charles Tolliver, Pharoah Sanders, Stanley Cowell, Reggie Workman) and an outstanding Freddie Waits performance (this got a good look from Ethan Iverson here), and Andrew Hill’s Grass Roots (Blue Note, 1968) featuring Lee Morgan, a set of Andrew Hill tunes that are halfway between say, Wayne Shorter’s writing for the Jazz Messengers and Hill’s own Point Of Departure-era music, a perfect vehicle for Freddie Waits.

Finally there is Lee Morgan (often called Lee Morgan The Last Session, Blue Note, 1972), the final studio recording of the Lee Morgan Quintet. Produced by George Butler, the quintet of Morgan, Billy Harper, Harold Mabern, Reggie Workman, and Waits is expanded to an octet, with the addition of electric bass (Jymie Merrit), flute (Bobbi Humphrey) and trombone (Grachan Moncur). On every track, Morgan, Waits, and company seek a common ground between free jazz, funk/soul/R&B, and Blue Note hard bop.

A standout cut is Waits’ own composition “Inner Passions Out” an epic, 17-minute journey which begins with a recorder and lots of percussion, builds to a trumpet solo during which Waits moves in and out of steady time. The tune then settles into a bass duet, followed by a meditative drum solo, and finally the four-on-the-rim straight 8th note feel and melody reappears.

Here’s a link to the “Blue Note” episode of Soul!, featuring Horace Silver, Bobbi Humphrey, and Lee Morgan with Freddie Waits. Is that Waits playing the opening drum solo?

After Morgan’s tragic death, another facet of Waits’ artistry began to appear: starting in about 1973, Waits began recording on mallet instruments. Bennie Maupin’s Buddhist-influenced classic The Jewel In The Lotus (ECM, 1974), begins with Waits playing marimba. Somehow, Waits, Billy Hart, and percussionist Bill Summers maintain an otherworldly stillness on The Jewel In The Lotus, even though all three are often playing simultaneously. Amazing.

The trend of expanding the percussion section reached some sort of apogee with M’Boom.

M’Boom, the jazz percussion ensemble started by Max Roach in 1970, was built around Frederick Waits and Joe Chambers; other founding members were Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, and Warren Smith.

Confusingly, M’Boom released three albums with the identical title of M’Boom Re: Percussion, on three different labels. The last one, recorded in 1979, was an early digital recording for Columbia, and is widely available.

Roach’s “January V”, in memory of Charles Mingus (who died on January 5, 1979) is an important piece. The tolling chimes, marimba rolls (Waits) and distant timpani thunder appropriately honor the great man’s passing, while the snare drum gives the piece a somber, martial character— brilliant composing for a percussion ensemble. I believe it is Waits playing the marimba solo on Roy Brooks’s “Kujichaglia”, a trance-inducing, New Orleans-oriented piece; someone surely has sampled this for a hip-hop track.

M’Boom is essential to the story of jazz drumming in the late 20th century and early 21st century. They were a social and musical experiment, a group whose legacy is still unsorted. To unpack everything M’Boom achieved and wanted to achieve requires another essay, one on which I am at work.

On the classic Bartz, Tyner, and Morgan records, Waits plays brilliantly but M’Boom gets closer to the heart of Waits’ contribution. One can draw a line from Waits, Chambers, Roach, et al, playing improvised solos on marimbas, vibes, and tympani in a concert hall to the AACM, to Tyshawn Sorey and beyond.

One of Waits’ final projects was Trio Transition, apparently a co-led band consisting of himself, bassist Reggie Workman, and pianist Mulgrew Miller. I’d only heard “Like Someone In Love” off their first album, Trio Transition (DIW, 1988), but on Discogs I picked up a copy of their second and final release, Trio Transition With Oliver Lake (DIW, 1989).

This is a great album— Waits’s energetic, ahead-of-the-beat feel creates a sense of excitement and edge, and he creates the common ground for Lake, Miller, and Workman. It also includes a great tune by Freddie, “Mr. Blackwell”, a series of whole-tone melodies that metrically modulates, connected by Waits’s drum solos.

“I always felt I could play anything if I could hear it and feel it, if it came from African continuum.”5

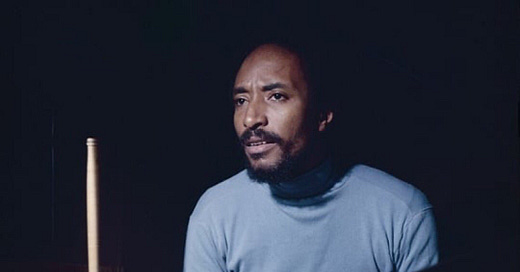

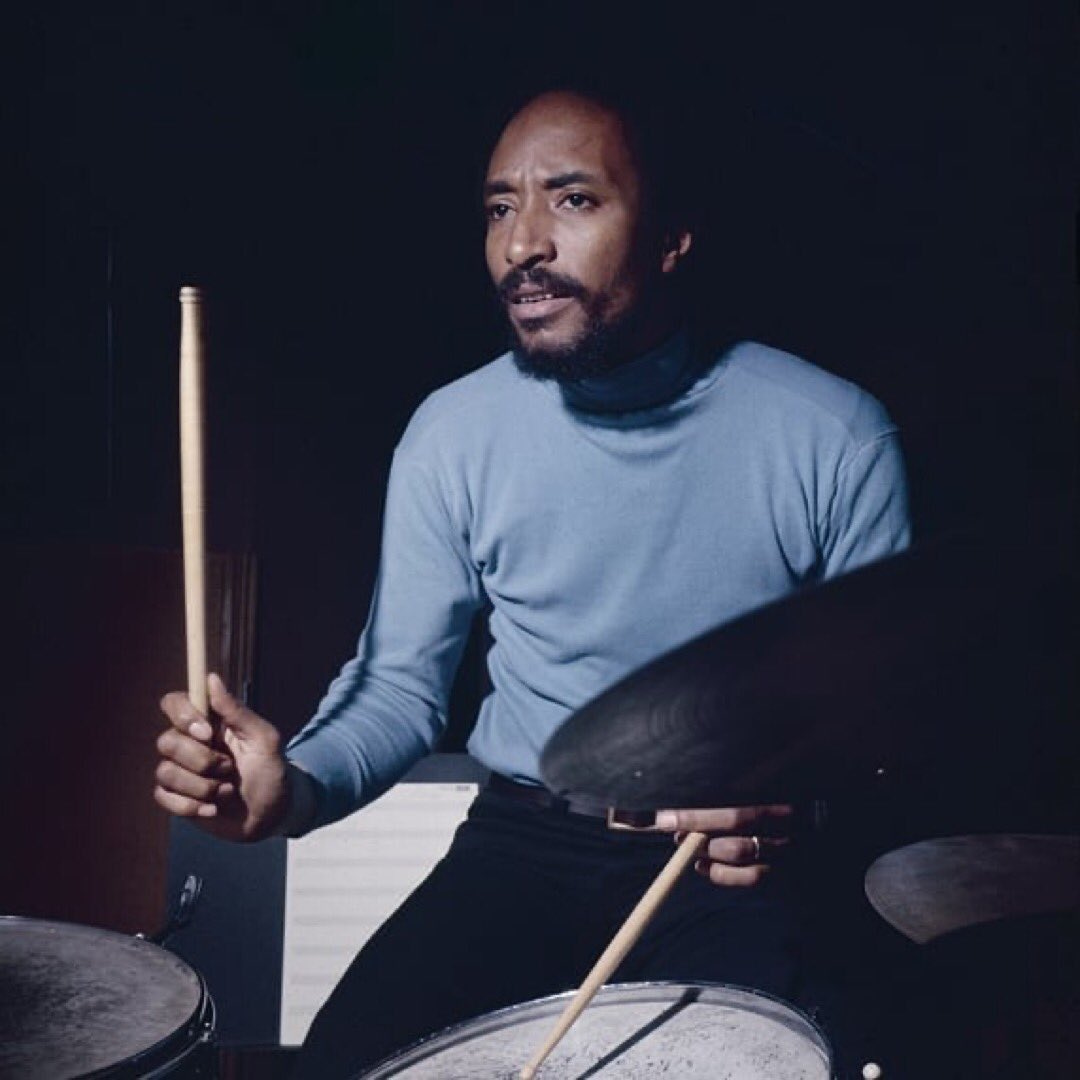

Frederick Waits died on November 18th, 1989, a tragic loss the music world and to his community. His son, Mr. Nasheet Waits, is one of the great drummers playing today.

Music today is all about rhythm, drums, and drummers: hip-hop, Tyshawn Sorey, Questlove, Terri Lynne Carrington, Anderson.Paak, on and on. This happy state of affairs is the result of the efforts of a huge number of drummers who came, did their thing loud and proud, and then left. It’s up to us to sort out and recognize their contributions.

Mr. Frederick Waits did more than his share. Let’s listen to “Dancing In The Street”, Time For Tyner, or Trio In Transition With Oliver Lake and be grateful for his playing. Let’s hear the fruits of his efforts everywhere.

“Frederick Waits: Life Experience” by Jeff Potter, Modern Drummer, February 1990.

Little Willie John had a hit with “Fever” in 1956; Peggy Lee wrote some new lyrics and vastly changed the arrangement and made “Fever” her signature song in 1958.

Wikipedia says it’s Marvin Gaye on drums on “Fingertips”. Marvin Gaye is not playing drums on this track. Marvin Gaye was well on his way to becoming a star attraction in March 1963, making it unlikely that he would play drums with the backing band on a “Motortown Revue” touring package. There is some grainy footage of a performance of “Fingertips” at the Apollo, and the drummer looks like Freddie Waits; he also sounds like Freddie Waits, and sounds just like the drummer on “Fingertips”, recorded weeks earlier at the Regal Theatre in Chicago. Finally, Freddie Waits says its Freddie Waits on “Fingertips”. Therefore, it is Freddie Waits playing drums on “Fingertips”.

Ibid.

Ibid.

See also Andrew Hill's "Lift Every Voice" session; the crack rhythm section with Richard Davis. The title track is along the the lines of a slow Afro-samba. The percussion part is intricate. As I understand it, Mr. Waits visited Brazil. The Mosaic Select MS-016 sessions are also worthwhile.

Kenny Barron’s New York Attitude is a personal favorite. Burning trio with Waits and Rufus Reid!