O'Neil Spencer: Swing, Shuffles, and "Stack O' Lee"

The drummer on "Loch Lomond" and with the John Kirby Sextet was a gifted singer who strongly anticipates R&B.

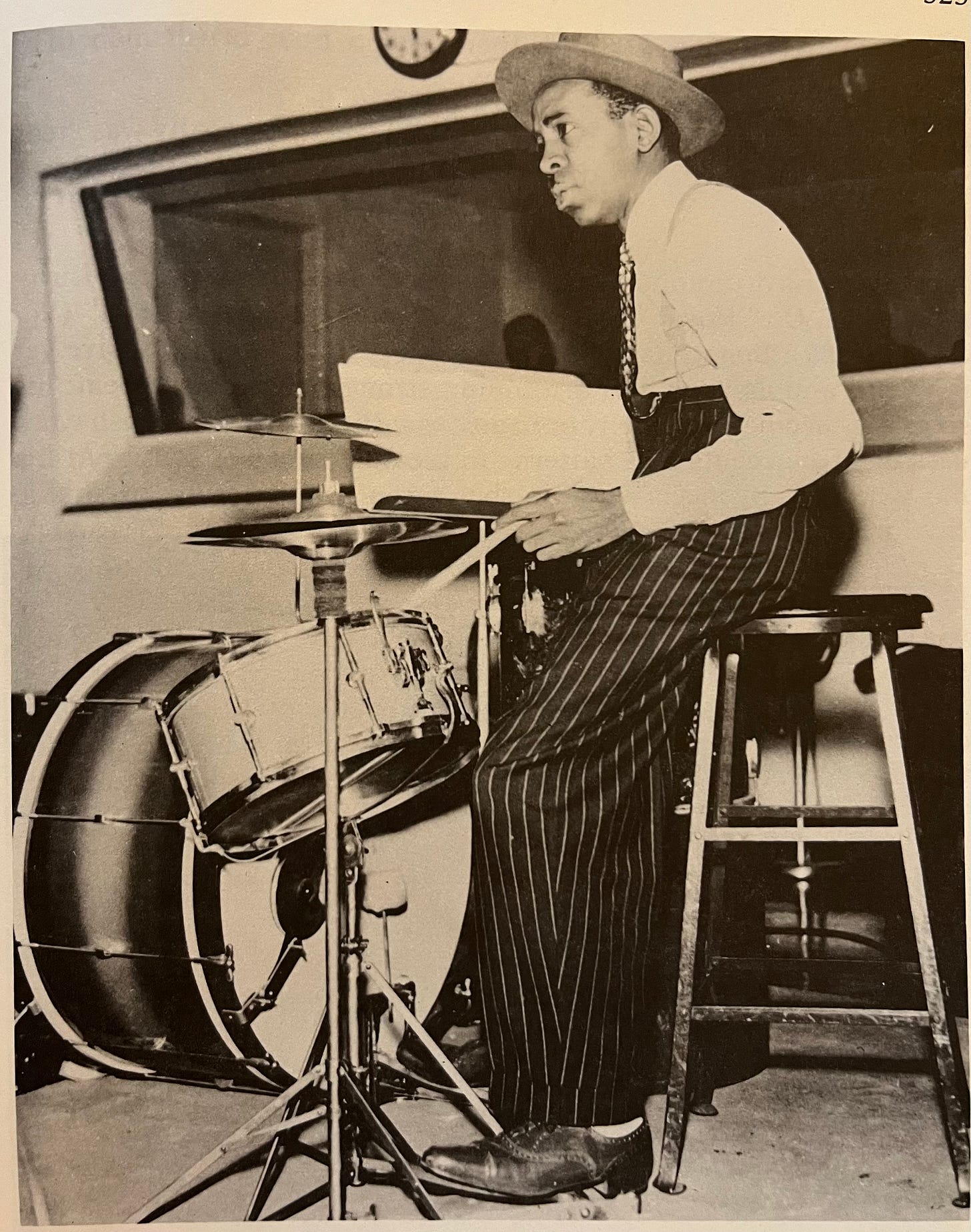

Last week, Ethan Iverson sent me a YouTube link to a record by organist Milt Herth from 1937, “Lost In The Shuffle”, featuring a trio of Herth, pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith, and drummer O’Neil Spencer. With nothing more than brushes on a snare, Spencer makes a lot of music. His charismatic beat holds the trio together and draws us in.

In the second chorus, Spencer starts singing— incredible! I didn’t know he was a singer, and had no idea there were singing drummers so far back.

1937 is 88 years ago. Herth’s organ, though expertly played, can sound old-fashioned to us. But nothing about O’Neil Spencer sounds old-fashioned; his beat feels contemporary and his voice engages and charms. He could have played like this yesterday and we’d be digging it today.

88 years from 2025 is the year 2113. I assume my recordings will sound hopelessly out-of-date in that distant, sci-fi-like year. But O’Neil Spencer and his cohort created modern rhythm; we’re still playing their beat, walking in their footsteps. He's right up to date. Time to learn about O’Neil Spencer.

We know Spencer’s name— Buddy Rich, Max Roach, and Philly Joe Jones mention him in interviews, while two books from the Nineties, Ron Spagnardi’s The Great Jazz Drummers and Burt Korall’s Drummin’ Men, have pages on him. John Riley’s The Art of Bop Drumming, now a standard text, recommends a John Kirby compilation with O’Neil Spencer1.

According to the references, O’Neil Spencer was born outside Dayton, OH in 19092, and was a professional drummer in Buffalo, NY by the late Twenties3. In the early Thirties, Spencer arrived in NYC, first gaining notice in the Mills Blue Rhythm Band4—incredible that ‘blues’ and ‘rhythm’ have been linked in music for nearly 100 years.

Spencer’s career seems to take off after playing on Maxine Sullivan’s “Loch Lomond”, a smash hit in 1937. I thought this record would be a novelty or curiosity, but I was totally wrong. Maxine Sullivan’s “Loch Lomond” is an artful and intelligent pop song, built around the new thing in music— the swinging eighth note. O’Neil Spencer was a master of the new rhythm, and his beat made the record a hit.

Listen close to Spencer on “Loch Lomond”: this is expert drumming. He follows the contour of the arrangement, first evoking Scottish marches, then swinging, thickening to a quasi-backbeat during the solos. Spencer is conducting the listener through the song with a great feel— exactly what a drummer is supposed to do, a totally contemporary approach. He set the standard we still aspire to.

“Loch Lomond” was arranged by Claude Thornhill (!!), composer of the almost-modal “Snowfall” (a hit when Miles and Coltrane were teenagers), who later hired Lee Konitz and Gil Evans and was a direct influence on Miles Davis’s Birth of the Cool. Except for Thornhill, the band on “Loch Lomond” was the John Kirby Sextet. Born in 1908, bassist John Kirby was a veteran of the two bands, both Black, who pretty much created swing music— Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb. Kirby knew something about what the new rhythm could do.

The Kirby Sextet with Spencer on drums was playing at the Onyx Club on NYC’s 52nd Street when “Loch Lomond” broke, and in 1938, they became a national act. Touring the country, bringing their virtuosic small-group jazz to a wide audience, Kirby and Spencer spread the swinging message. From our vantage point, we hear the Kirby band anticipating Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Pettiford, and Don Byas— the first 52nd Street bebop band.

Small wonder then that “Loch Lomond”, a brilliant mash-up of European melody and American swing, with links to the future sounds of bebop and R&B, was such a hit. The brightest young minds in jazz went to work on a beloved folk tune, centering O’Neil Spencer’s swinging beat to create a commercial and artistic success.

From 1938 to about 1944, the John Kirby Sextet with O’Neil Spencer on drums was one of jazz’s most popular bands. Called “the biggest little band in the land”, the Kirby Sextet’s dazzling tutti ensembles were held aloft by Spencer and Kirby’s strong and dancing 4/4. Listening to these records for this piece, I’ve come to really love their beat.

They made a lot of recordings; here’s two choice cuts of O’Neil Spencer with John Kirby:5

John Kirby: “Mr Haydn Gets Hip” (studio recording made for radio broadcast, recorded May 1941). I don’t know what Haydn piece this is based on, but it summarizes the fun and wide appeal of the Kirby Sextet. Spencer grabs us right away, switches from brushes to sticks, conducting us through the piece with his charisms and musicianship.

John Kirby: “Rehearsin’ For A Nervous Breakdown” (same session, May 1941). What a tempo, what a natural flow Spencer has in the ensembles; I just love his gorgeous press roll and soft cymbal crashes. With a beat like that, had Spencer lived into the modern jazz era (he died of tuberculosis in 1944), it’s easy to imagine Thelonious Monk or Dizzy hitting him up for some dates. I’m impressed.

When he wasn’t touring with Kirby, Spencer did a lot of recording sessions, playing drums but often singing as well, at least according to the Lord Discography. Check out O’Neil Spencer singing and playing on two Decca singles from 1937 and 1938. Is he our earliest singing drummer?

Milt Herth: “The Dipsy Doodle” (Decca, 1937). Organist Milt Herth is on Wikipedia; “The Dipsy Doodle” is the A side of “Lost In The Shuffle”. O’Neill’s brushes are the main ingredient— his thick, raspy sound on the snare grabs the ear and pulls the music together. When Spencer sings, the backbeat looms, the rhythm and blues zeitgeist begins to materialize, the future is clear.

Johnny Dodds, “Melancholy” b/w “Stack O’Lee Blues” (Decca, 1938). On “Melancholy”, Spencer lays down a buoyant and detailed beat for New Orleans clarinetist Johnny Dodds, known to us from Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five. I love the way O’Neil enters after guitarist Teddy Bunn’s intro— again, his timekeeping with brushes on a snare is a complete musical experience: there’s nothing simple about this. O’Neil’s vocal on “Stack O’Lee” is just great— engaging and memorable. Quite a challenge to sing all those words and play like that, in an era before endless takes and easy edits. Add an electric guitar and some louder drums, and we’d have an R&B classic. Bravo O’Neil Spencer!

Writing this piece, learning about O’Neil Spencer, I was struck by how strange swing music must have been when it was brand new. A truly avant-garde proposition, a skewering of the strong, straight rhythms we were accustomed to, swing would have been as beguiling as it was elusive— hearing a band that could really swing would have been rare and thrilling indeed.

After only seven tunes, O’Neil Spencer is coming into focus, so clear is his contribution: an accomplished professional, a master of the swing rhythm who could hear arrangements, at ease on the bandstand and in the studio. His beat worked with everyone, and he sounds great in diverse settings— New Orleans jazz, swing, pop, R&B. Spencer could do it all, with style, class, and individuality.

But there’s something more: O’Neil Spencer is a singer—a singing drummer. It’s a major part of his identity— the Lord Discography lists him singing with the Mills Blue Rhythm Band as far back as 1932. I recognized O’Neil Spencer’s name because he was vividly remembered by Buddy Rich (born 1917), Philly Joe Jones (born 1923) and Max Roach (born 1924); they spoke of him decades after his death. What are they trying to tell us? What’s being alluded to?

If Rich, Jones, and Roach first heard O’Neil with Maxine Sullivan and John Kirby in 1937 (they could of course have heard him years before), they would have been 20, 14, and 13 years old, respectively. I think this is the answer— O’Neil Spencer was a part of their youth. When Max Roach mentions Spencer to Art Taylor in Notes and Tones, he’s remembering a drummer he heard in his adolescence, when indelible impressions are made.

Imagine seeing O’Neil on the bandstand with John Kirby: it’s a crowded nightclub, he’s driving the band with a pair of brushes, nailing the arrangement, playing off the dancers, sometimes even taking the lead vocal. Spencer’s good-looking, perfectly dressed, the center of the action, showing what the drumset can do, what a drummer can be. It would be an unforgettable night for anyone, especially for a young drummer.

I’ll make a leap: for Buddy, Philly Joe, and Max, O’Neil Spencer was a great drummer, yes, but he was something much more. He opened doors, showed what was possible.

Swinging and singing in the top band in the land, he was something that Buddy, Philly Joe, and Max Roach all wanted to be, and eventually became: respected by musicians and known to the public, O’Neil Spencer was a star.

Now I see the importance of ‘keeping the name out there’. Thanks Riley, Korall, and Spagnardi for listening to what Buddy, Philly Joe, and Max had to say— slowly, slowly, I’m getting the message.

Lewis Porter points out the many (not all) swing musicians were born around 1910, while the folks who created bebop were (often) born closer to 1920. This is helpful and points to Kenny Clarke’s outlier status— born January 1914, Clarke is right in the middle of the swing-to-bop continuum.

Though Buffalo had a segregated musician’s union, I bet drummer Sam Sokoloff heard Spencer, and may have passed something of O’Neil’s onto his son Melvin, who is of course our Mel Lewis.

Pianist Edgar Hayes, who was with Spencer in the Mills Blue Rhythm Band, led his own band in the late Thirties, recording the original “In The Mood”, featuring Kenny Clarke on drums.

I’ve assembled this playlist of O’Neil Spencer by toggling between Discogs, the Lord Discography, YouTube, and Wikipedia— I have no special info, but I have checked, double checked, and cross-referenced these resources to make sure we’re hearing O’Neil Spencer. If there’s an error here, please alert me immediately, or sooner.

A name I certainly knew but little more. O’Neill Spencer given both recognition and context. Thanks. A bit of a tangent but but with some pertinence to the the Johnny Dodds release featuring O’Neill’s vocal, is this gem of a book: Stagolee Shot Billy - Cecil Brown, Harvard University Press, 2004

Thanks