Max Roach always gave credit to his influences. Roach paid tribute and material aid to drummer Jo Jones, who, with Count Basie, suggested how flexible and joyous 4/4 swing could be. From Sid Catlett, Roach heard progressive ideas flowing from older, established practices. Chick Webb showed Max what a drummer could be: a successful bandleader, a figure of dignity and accomplishment who used the instrument to express his community’s deepest wisdom.

I’ve written here about Max’s work as an accompanist, how his declarative comping and time playing are the rebellious, ambitious aspects of bebop made manifest. But neither Jones, Catlett, nor Webb made their name by swinging on a ride cymbal and comping on the snare drum, which was Max’s whole thing.

If none of his acknowledged heroes did the basic Max thing, then where did he get it?

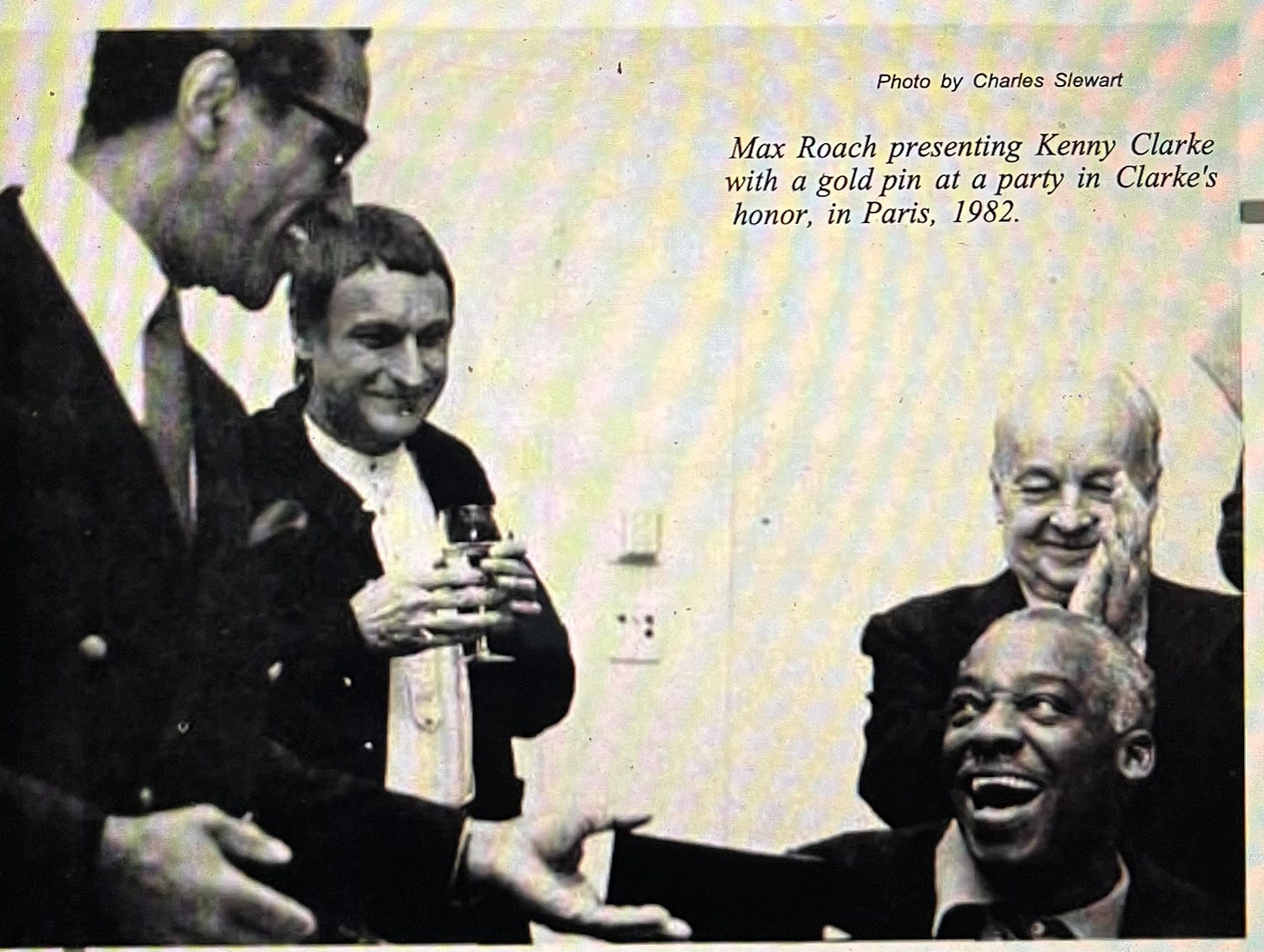

The picture above, from 1982 in Modern Drummer by photographer Chuck Stewart, tells the story. It’s a glimpse at Max’s immediate forebear, from Max’s perspective.

In the photo, drummer Kenny Clarke is seated, while Roach, of regal bearing and attire, stands and gestures towards Clarke with both his hands, in a sort of ‘as-the-master-says’ kind of pose.

Clarke and Roach are making eye contact and smiling broadly; Clarke’s smile in particular is lighting up the whole room. In the background, two onlookers drive the point home— Max Roach is honoring Kenny Clarke, for it is Clarke who was Roach’s most direct predecessor.

But more than that, Kenny Clarke was an original thinker and technical innovator; he simply must be one of the most unique minds in 20th century music. The basic template of jazz drumming— time on the ride cymbal, four soft poofs on the bass drum, hand clap on the hi hat, and clave fragments on the snare drum— was Kenny Clarke’s thing before it was Max’s, before it was anyone’s.

Many drummers almost did it or sort of did it, but Kenny Clarke really did it. Thankfully, we have some audio.

In the beginning, drummers played time on the snare drum and bass drum, and went to a cymbal for a chorus or two.

Here’s Baby Dodds playing Jelly Roll Morton’s “Wolverine Blues” in 1946. I love this track— Dodds sounds so great. Though it was made in the Forties, this is pretty much what jazz drumming was at the beginning.

But society was changing, jazz was evolving, and the bebop drummers, led by Kenny Clarke, translated the energy and drive from snare drum and bass drum to a ride cymbal.

The eccentricity of this idea is hard to convey. Using a rolled-up newspaper to pound a nail into a wall is sort of analogous to swinging a band with a cymbal, which is what Kenny Clarke did, what I heard Billy Hart do at the Vanguard in April, what I heard Jeff Hirshfield do at Drom a few nights ago.

Kenny Clarke wasn’t the first drummer to do this, but he was the first to build a style around it. His innovation didn’t arrive out of nowhere— drummers had played on dark-sounding Chinese-made cymbals behind hot soloists since at least 1930. Nevertheless, Clarke had a new idea when he made the ride cymbal the center of his universe.

The “Kenny Clarke made bebop when he went to the cymbals” axiom is repeated endlessly in the literature; it’s practically a commonplace. But as I listened to these Minton’s recordings over and over, Clarke’s idea began to seem deeply strange: why did he want a thin, ringing, hard-to-control cymbal to do what his snare and bass drum did just fine?

We’ll never know, but here are a few words from Kenny:

We were playing a real fast tune once with Teddy Hill— “Old Man River”, I think— and the tempo was too fast to play four beats to the measure, so I began to cut the time up.

But to keep the same rhythm going, I had to do it with my hand [i.e. on a cymbal] because my foot just wouldn’t do it.

When it was over, I said “Good God, was that ever hard.” So then I began to think and say “Well, you know, it worked. It worked and nobody said anything, and it came out right. So that must be the way to do it.” Because I think if I had been able to do it [the old way, i.e., four beats on the snare drum and bass drum], it would have been stiff. It wouldn’t have worked.

—Kenny Clarke to Helen Oakley Dance, September 1977, Jazz Oral History Project

I used to say, "There must be an easier, simpler way to get the same effect and keep the band together without straining your arms."

I thought about it for many years. I was still basically playing the old way, but every once in a while I'd go up there and do that cymbal thing.

Ding-ding-a-ding.

—Kenny Clarke to Ed Thigpen, Modern Drummer, February 1984

Kenny Clarke (who was named either Kenneth Spearman Clarke or Kenneth Clarke Spearman at birth— readers, fill me in) was born in Pittsburgh, PA on January 9, 1914— the same year as Sun Ra, just 26 months after Jo Jones, and almost ten years to the day before Max Roach.

Clarke’s musicianship was noticed right away. He was a professional musician before he was 18, and was playing with national acts in his early twenties. In 1937, Clarke appears on record for the first time, in pianist Edgar Hayes’s band. Hayes was well-known— he was affiliated with Ellington manager Irving Mills and filled in for Duke at the Cotton Club.

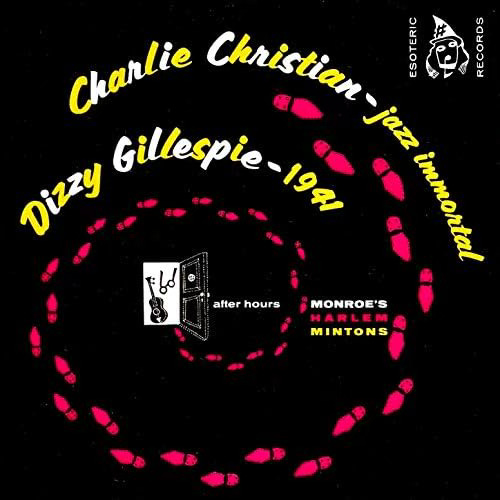

That’s Kenny Clarke on Hayes’s original version of “In The Mood”, released in early 1938, well over a year before Glenn Miller recorded it. But by the time “In The Mood” was released, Clarke was already connected to both Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk:

Robin D. G. Kelley’s definitive Monk biography has Clarke in Thelonious’s social and musical circle in late 1936 or early 1937;

In Gillespie’s own memoirs, To Be Or Not To Bop, he mentions gigs with Edgar Hayes in 1938, when Clarke was in the band.

One of the most famous photos in jazz was taken by William Gottlieb in 1948, outside Minton’s Playhouse, the Harlem club where, according to legend, bebop was born.

At the far left, Thelonious Monk’s charisma is palpable: perfectly dressed, confident, at ease, ready for all comers. Next to Monk, and nearly matching him for charisma are Howard McGhee, the legendary trumpeter, and to McGhee’s left, Roy Eldridge, the trumpet player who most directly anticipated Dizzy Gillespie. On the far right is tenor saxophonist Teddy Hill, the manager of Minton’s.

It’s a powerful image: the musicians are impeccably attired, and seem open, fearless, and united. They have, to various degrees, found a way to live on their own terms; it’s a vision of a better world. It’s at Minton’s that Kenny Clarke established his reputation as the original bebop innovator.

As Robin D. G. Kelley has pointed out, owner Henry Minton’s connection to Local 802, the NYC musician’s union— Minton was 802’s first Black delegate— meant that his club, in effect, catered to musicians. By intention and design, Minton’s was a space for players to network (as we now call it), jam, get a meal, and feel at home. Minton’s is a countercultural response to the Swing Era music business of hotel ballrooms, radio spots on national networks, readers’ polls, and so on.

In late 1940, Teddy Hill hired Kenny Clarke, age 27, to form a house band for Minton’s. Clarke assembled trumpeter Joe Guy, bassist Nick Fenton, and Thelonious Monk; the group opened in late January or early February 1941, working nightly Wednesday through Monday.

At that moment, Charlie Parker was 21, working with Jay McShann on the road; Max Roach was 17 years old, living in Bedford-Stuyvesant; Miles Davis was in Illinois, 15 years old. We are now at the precipice.

Incredibly, a lot of music was recorded at Minton’s, much of it featuring Kenny Clarke.

Columbia student Jerry Newman seems to be responsible for most of it, lugging his portable disc-cutter to Minton’s and Monroe’s Uptown House in 1940 and ‘41, capturing less a new music and more a new sensibility, a sense in which the music’s value was self-evident, not dependent on 3,000 well-dressed dancers and an NBC radio spot. Listening over and over, the music seems revolutionary, not in musicological terms (harmony, rhythm, melody, form), but socially.

Indeed, Clarke, in his conversation with Thigpen, emphasizes how much older musicians were a part of the scene at Minton’s:

“Charlie Christian contributed a tremendous amount to the new music and we were always swinging hard when he came up….we just called it modern music. Musicians from all over the country— Dizzy, Georgie Auld, Roy Eldridge, even Lester Young— would come around a lot. Lester loved what we were doing.”

This was independent music, made by brave and uncompromising musicians, on their own terms.

What’s needed is a comprehensive boxset of recordings from Minton’s. Right now, everything is scattered across at least a half-dozen LPs, some streaming, some not. These five tracks all feature Kenny Clarke, and most feature Thelonious Monk. I’ve created a YouTube playlist, and individual links:

“Swing To Bop” a.k.a. “Charlie’s Choice”, a.k.a. “Topsy”, originally composed by Eddie Durham; Joe Guy and unknown, trumpet; unknown tenor sax; Kenny Kersey, piano, Charlie Christian, guitar; Nick Fenton, bass; recorded May 12, 1941. Brushes all the way from Clarke; he’s conversing with Christian in the exact way I and everyone I admire would try to converse with a soloist today. Christian and Clarke have a deep rapport, the beat is so exciting, and the thick, deep sound of Clarke’s snare is just about perfect.

“I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”; Joe Guy, trumpet; Don Byas, tenor sax; Thelonious Monk, piano; unknown, bass; possibly recorded on May 20 or 21, 1941. Streaming on Don Byas: Midnight At Minton’s (High Note), recorded by Jerry Newman. Clarke’s beat is big and buoyant enough for a big band, yet he’s improvising as freely as the soloists— snare accents, tom fills, open and closed hi-hats, and then behind the trumpet solo, there it is: the modern jazz ride cymbal.

“Indiana”, same personnel, date, and streaming source as “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love”. Clarke was developing his ideas slowly; he goes between ride and hi-hat for Monk’s solo, and it’s revelatory when he finally opens up on the ride cymbal exactly as a drummer would today. Clarke sang his own song, danced to his own beat, lived on his terms. We’re so lucky this was recorded.

“Sweet Georgia Brown”, Hot Lips Page, Joe Guy, trumpet; Jimmy Wright, tenor sax; Thelonious Monk, piano; unknown, bass. Streaming as part of Hot Lips Page: After Hours In Harlem (High Note). Monk’s opening solo is startling; he was a perfectly developed voice at age 24. Like “Indiana”, Clarke plays hi-hats for Thelonious and then goes to ride cymbal for the trumpet solo, back and forth for the whole tune. Meaningful change comes slowly.

“Rhythm-A-Ning”, Joe Guy and others, trumpet; Kermit Scott, tenor sax; Charlie Christian, guitar, Nick Fenton, bass. From Trumpet Battle At Minton’s, (Xanadu). Some sources list Monk here, others don’t. Clarke’s concept is deepening— the cymbal beat is driving the band, Clarke’s beat is even more infectious, and his snare drum interjections now push the music forward, as opposed to being comments and chatter. Doubt this was called “Rhythm-A-Ning” at the time, this is Mary Lou Williams’ phrase from “Walkin’ and Swingin”.

In the early 20th century, the African American community created something so profound that I’m writing of it today; not to be grandiose, but I’ve based my life around what they created. So I try to pay attention to the background human noise on these recordings too.

The chatter and clinking glasses while Monk solos and Clarke swings on a cymbal? That’s the sound of the community that gave us Kenny Clarke, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and all that followed.

Doubtless a good portion of the voices we hear are musicians, professional and amateur, but surely we’re also hearing ordinary citizens doing what people do in bars. These are the folks for whom the music was made. These unknown names are an essential part of this story.

Check out "Willow Weep for Me" on Dexter Gordon's OUR MAN IN PARIS. Klook's ride pattern is a mixture of dotted-eighth-sixteenth and eighth-note triplet subdivisions. Unique, to say the least!

Thank you so much for this post! A story I never tire of telling is when I moved to Paris in 1979 and, looking in the local music listings, saw that Kenny Clarke would soon be playing at a little club, Le Dreher. In those pre-Internet days I knew of him only as a name in books and had assumed he was dead. I went along and there he was, in a trio with organist Lou Bennett and guitarist Christian Escoudé. He seemed personally warm, affable, humorous and urbane, chatting and joking with the bartender in French between sets. And the drumming was joyous and charismatic, so swinging I literally got a cramp from tapping my foot. I think the single luckiest break in my life as a jazz fan was serendipitously ending up in the same city as Klook. I saw him often in the clubs during the five years or so between my arrival there and his death. I love your insights into how he arrived at that brilliantly effective style.