Max Roach at 100: Part 3

Max Roach duos, 1976-1982.

“The information as to the technique of the music, is usually passed down, as Charles Mingus has often said, from mouth to mouth. So it’s not a matter of saying I’m doing anything that anybody else isn’t doing.”

—Max Roach, 1980

In 1968, Max Roach, age 44, inheritor of an oral music tradition going back to the 19th century, had been the leading drummer in jazz for over twenty years. He was signed to Atlantic Records, who had released Drums Unlimited (1966) and Members, Don’t Git Weary (1968). Both are classic albums, full of vitality and new ideas, featuring Roach with the best young players of the era: Freddie Hubbard, James Spaulding, Ronnie Matthews, Charles Tolliver, Gary Bartz, Stanley Cowell, and Jymie Merritt.

But Roach was under pressure to deliver a hit. As Max himself relates in the essential documentary The Drum Also Waltzes, Roach thought that an album of the classic spirituals might satisfy “the brass at Atlantic”. The result was Lift Every Voice And Sing (1971), where his quintet featuring Billy Harper, Cecil Bridgewater, and George Cables played alongside the J.C. White Singers, a renowned Brooklyn gospel choir.

Despite the quality of Lift Every Voice And Sing, evidently it wasn’t the smash “the brass at Atlantic” were hoping for. After the album’s release, Roach’s Atlantic deal fell through, and in 1972, he took a position at University of Massachusetts Amherst. For the first time since 1954, there was no active-duty Max Roach group.

After arriving at U Mass Amherst, Roach first devoted himself to M’Boom, the percussion ensemble he founded. By 1976, M’Boom had two albums and a European tour under its belt; perhaps Roach felt that now was the time for a new challenge. So Max Roach, bebop innovator, the thoughtful and even cerebral improviser, dove head first into the thickets of free improvisation.

The setting he chose to address the new sound was a duo. In fairly quick succession, Max Roach instigated five duo encounters with:

Archie Shepp

Abdullah Ibrahim

Anthony Braxton

Cecil Taylor

Connie Crothers

By this time, Max Roach was one of the few beboppers still active, and the only one of his stature to embrace free music. Take a moment and imagine another luminary like Max doing the same: Thelonious Monk with Ornette, say, or Dizzy Gillespie with Ed Blackwell. Or Sonny Stitt with Muhal Richard Abrams. Certainly tantalizing, but for whatever reason, these didn’t happen.

This little thought experiment puts Roach’s bravery in bold relief. Whatever else Max Roach was doing at this time— asserting control over his career, bucking the record companies, growing his audience— he was most certainly taking a big chance musically.

I’m glad he did. In this period, Roach made some great records for us to ponder, study, and enjoy. The possibilities they suggest are being explored right now.

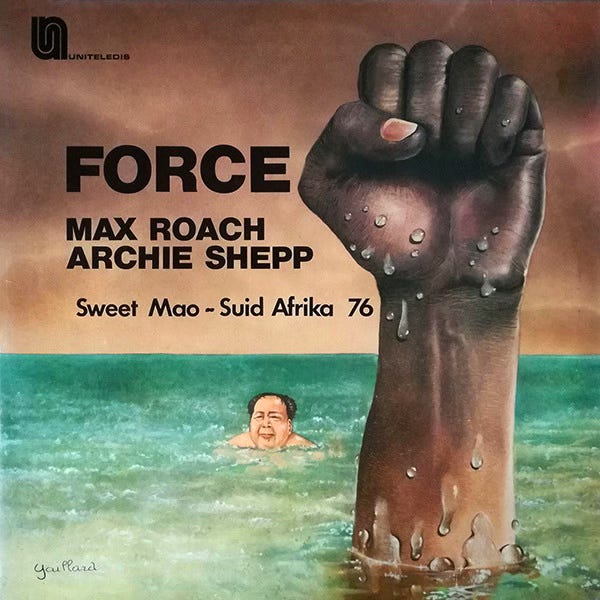

Roach’s first duo project was with tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp, recorded in Paris and released as Force (Uniteldis/Base Records, 1976). (Here’s a link to a YouTube file, I got my copy for $20 on Discogs.) A double album of four side-long tracks, each organized around a specific drumset pattern or idea, according to Roach, the album was made almost by accident, at the behest and funding of the Italian Communist Party while Roach was on tour. There’s probably more to it than that: if readers have more info, please chime in.

Regardless of the circumstances, Force is a fascinating and rewarding listen. On “La Preparacion”, while Shepp improvises, Roach returns throughout to a slow, descending flam tap on the small tom, middle tom, and floor tom, the theme of the piece. While Shepp blows on “La Marche”, Roach plays exclusively on the snare drum, bass drum, and hi hat, the military wing of the drumset. “Le Commencement” is some lovely 4/4 swing, with a great “Misterioso” quote from Shepp about midway through; when Max opens up on the bass drum, ghosts of Sid Catlett, Jo Jones, O’Neill Spencer, and Chick Webb are present. “Suid Africa 76” is built around a familiar Roach 12/8 pattern, heard in some form on most of his recordings going forward.

Shepp of course is wonderful throughout, playing motifs and translating Max’s intention and melodies to the saxophone. Roach and Shepp are perfectly simpatico, and the album should be counted as one of the great tenor/drum duos, alongside John Coltrane and Rashied Ali’s Interstellar Space or Dewey Redman and Ed Blackwell’s Red and Black. Force is an auspicious beginning1.

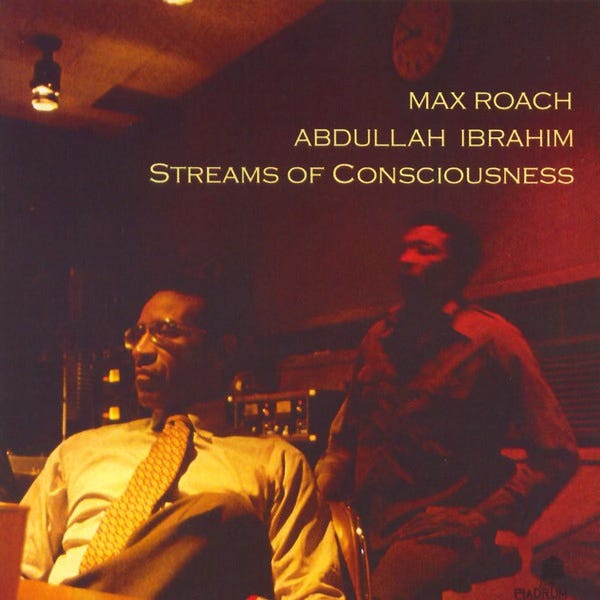

Max Roach was one of the first to connect the struggle of Black Americans for equal rights to the struggle of African nations against the legacy of colonialism. As the composer of “Tears for Johannesburg” in 1960, a time when no one in American music was talking about South African apartheid, and then of “Suid Africa 76”, it was a fitting statement for Max to record Streams Of Consciousness (Baystate, 1977), with pianist and Capetown native Abdullah Ibrahim, then known as Dollar Brand.

Here’s Roach’s own comments from the album jacket:

This music is an expression of pure improvisation. Mr. Brand (Ibrahim) and I had no rehearsals or plans (written or otherwise) as to how or what we were going to record. We met at the studio, sat down to our respective instruments and commenced to perform. Our becoming musically acquainted was both challenging and enjoyable. The resulting cohesiveness, I am sure, had much to do with our environmental similarities. —Max Roach, 1977

Streams Of Consciousness is engaging, patient, and inviting. According to Phil Schaap, a student of Roach’s and one of his most dedicated supporters, this was the duo album dearest to Max. The blend of Ibrahim’s expansive, suggestive sensibility with Roach’s logical, challenging disposition can be intoxicating. For those interested in this period of Max Roach, start with Streams Of Consciousness. It’s a gem.

The title track is an improvised, side-long, multi-movement suite. From the opening church-like piano solo to the closing minor key waltz, I simply love it. Roach and Ibrahim are co-composing as much as they’re improvising.

“Acclamation” has a righteous old school bounce. Max’s four-on-the-floor is loud and high in the mix, Ibrahim’s improvised song is beguiling; when it transitions to something resembling a calypso, the only sensible reaction is to stand up and cheer. I beg forgiveness for my ignorance: readers, if you know the name of the style Ibrahim is referencing at the conclusion of this track, please let me know!

On “Consanguinity”, Roach holds down a version of his epochal “Un Poco Loco” beat while Ibrahim accompanies, not quite settling into a vamp. When he reenters, the piece starts coming together. Eventually Max relents, and joins Ibrahim on a stirring re-cap of the chord changes that opened the album, a just-about-perfect conclusion.

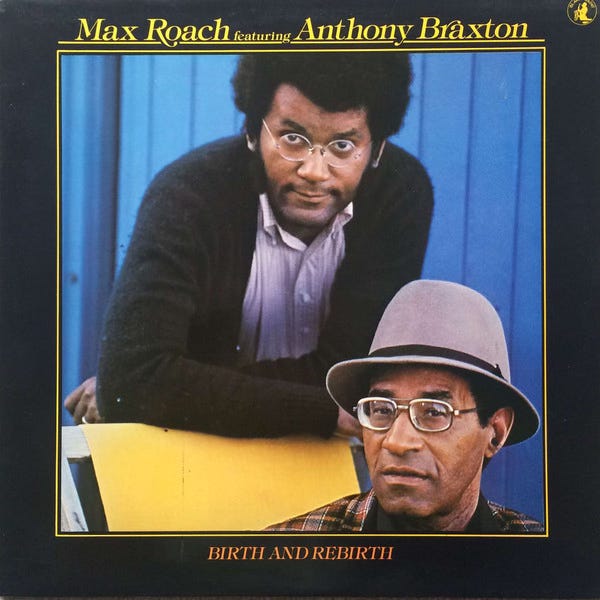

Birth And Rebirth (Black Saint, 1978), Max Roach featuring Anthony Braxton, was the next duo encounter. Braxton and Roach helpfully provided all the context we need:

The music in this album is a result of our belief in a continuum that links the present with the past. Our spontaneous improvisations are true to those well defined principles basic to African American culture. Thank you for listening.

—Max Roach and Anthony Braxton

I’m struck by how effortlessly Roach connects with Braxton, and vice versa. But then, they have much in common: composers, intellectuals, experimenters both, Roach and Braxton are, from one angle, birds of a feather.

Birth And Rebirth is easy to find, streaming on Apple Music, and the highlights are many. On “Birth”, a sopranino/cymbal duet gives way to what momentarily sounds like “Just One Of Those Things” at a Max Roach tempo. Roach arrives at a gently swinging waltz on “Magic and Music”, and Braxton, on soprano, goes right with him. Here, Roach is playing very softly, letting listeners savor his lovely time feel and developed touch.

Some of the transparent textures and questioning atmosphere of the early AACM is present on “Tropical Forest”, Braxton and Roach sort of co-existing, while “Dance Griot” is in Max’s chugging 4/4, and he and Braxton compose a tune together. Finally, on “Rebirth”, Max again unleashes his up-tempo fire and Braxton, on alto, embraces the moment. On this track, Roach’s bass drum is a concert in itself.

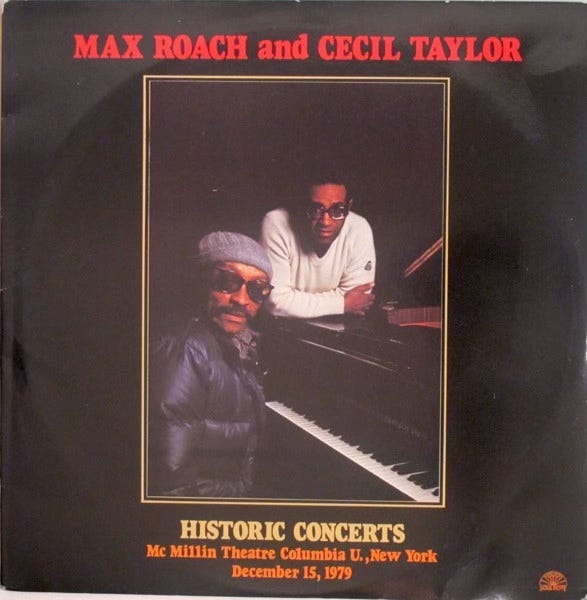

The Max Roach-Cecil Taylor duo concert of December 15th, 1979 was one of the major jazz events of the period. We can sense how big it was just by the coverage it received— Stanley Crouch, Robert Palmer, Lee Jeske, and Gary Giddins all published notices of the concert, included in the liner notes to Max Roach and Cecil Taylor, Historic Concerts (Soul Note, 1980), streaming everywhere. Here’s a YouTube link.

It must have been seismic: you can hear the excitement and anticipation in the crowd loud and clear on the recording. In fact, it’s easy to trace the line from the Roach-Taylor concert to any number of Eighties developments, especially the cross-genre experiments of John Zorn, Hal Wilner, and others. Those must in some way have been informed by Roach and Taylor’s encounter. But that’s just one line of influence; I could do an entire essay exploring all the reverberations from this one night. Anyway you look at it, Roach and Taylor are a classic and influential Seventies duo.

Best to let Max speak:

“Cecil Taylor is more in the mold of a Duke Ellington, or a Bud Powell, for example, than someone who would imitate these people. From a creative aspect, they are people who dare to think for themselves and introduce us to new ideas and new forms, still in the tradition of this area of American music that we call jazz.”

…I just enjoy working with different areas, not just staying with a format, say a quintet or quartet. I enjoy working with say, classical musicians, I enjoy working with breakers and rappers. It stimulates me, because I remember when I was there too. And I must say that Cecil Taylor is one of the high points of my musical career….

…This is the American way of doing things. Our whole culture is like this. Look at our architecture, it has a little bit of everything…we are multi-racial, multi-religious, multi-everything…it’s a cross-cultural place.”

—Max Roach in 1980, on working with Cecil Taylor, from “Interviews, pt. 1”, included on Historic Concerts (Soul Note, 1980).

It’s hard to describe Taylor’s music in any words that honor his integrity and intensity, which seems to be the point of Taylor’s music: to transcend language and go to a place that can’t be described, only experienced.

But I can point to a few standout moments. Roach and Taylor’s brief solo pieces, which opened the concert, are beautiful; Max working a simple four-beat pattern, Cecil rhapsodic and Ellingtonian. In the first set, the energy is mostly at a fever pitch, which, given the excitement of the event, was unavoidable. Overall, Taylor and Roach seem to be playing in parallel, co-creating and staying in their respective lanes, but the unison grand pause at 23:48 makes me wonder.

The second set feels more relaxed and playful overall; Max and Cecil have proved the experiment works, and now they can enjoy it. There is a near-perfect unison at 22:27, which simply appears and vanishes. It’s as if they both requested and mutually granted each other a moment of the simplest togetherness. I’m sure there are many micro miracles like this scattered across the album— I’ll keep listening.

The more I listened, the more details I heard, and the more I enjoyed the music, sensing their partnership, a willingness from both Taylor and Roach to go outside their comfort zones, and a shared experience— Max has cracked the code, and Taylor lets himself be celebrated by Roach. Max is so inventive and flowing, and Cecil is connected to the very heart core of jazz.

Stanley Crouch wrote about Max Roach returning to the Vanguard with a working band for the first time since 1971 soon after the duo with Taylor. This concert seemed to say it definitively: Max Roach was back. But he wasn’t done with the duo.

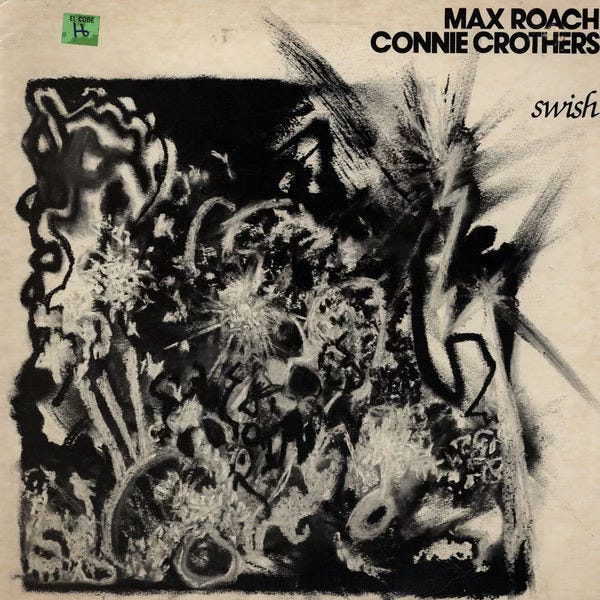

Swish (New Artists, 1982) was recorded with pianist Connie Crothers, a student of Lennie Tristano’s who in her own voice synthesized Tristano’s legacy, free improvisation, and 20th century composition. Produced by Crothers and Roach, with Roach’s son Raoul thanked in the liner notes, Swish was released on New Artists, a label run by Crothers, perhaps with some help from Max. Swish is almost a family affair, currently available for purchase from New Artists here, and the entire album is on YouTube here.

Roach is an ideal duo partner for Crothers, as familiar with Tristano, free improv, and composers as she was. Compared to Cecil, Crothers is precise and methodical, carving out discreet zones to occupy, and you can feel (in a good way) her consciously making choices. Roach, using vocabulary familiar to us by now, thrives in this setting.

The ‘classical-adjacent’ feel of Swish gives it an up-to-the-minute quality; there’s much interest in this sort of improvised/classical hybrid right now. It’s startling, though not surprising, to hear the grand master Max Roach play music that would be right at home at Ibeam, the Stone, or Roulette in 2024.

On “Symbols”, the album opener, Crothers’ identity is front and center: she has her own vocabulary, and she’s a virtuoso— every note sings. Her clarity is startling. Max’s cymbals and rims provide a counterweight to Crothers; the track could go on forever. So could “Let ‘Em Roll”, as Crothers plays against, then joins, Max’s tom-tom melodies.

On “Creepin’ In”, Max uses his “Drums Unlimited” hi-hat pattern while Crothers plays in the lower register. The tension mounts— it starts sounding like a fast 4/4— and then Max joins her, playing one of his tempos. Crothers spins out in her right hand, then hovers down in the low register while Max solos, creating a texture I’ve never heard before. Crothers is so impressive— her energy never flags, her ideas just flow.

By this time, Roach was a veteran free improviser, never lacking for an idea or direction. While the album is relaxed in comparison to the high-stakes games of Cecil Taylor and Anthony Braxton, Swish lets us celebrate Crothers’ and Roach’s unique connection and individual accomplishment.

Roach recorded other duos, including a 1989 reunion with Dizzy Gillespie, a 1995 concert with Mal Waldron, a 2002 encore bow with Clark Terry, as well as further concerts with Crothers and Ibrahim, even a second encounter with Cecil Taylor. But this series of duos can be heard as a single experience, when a great artist took firm hold of his career and placed himself in a challenging new environment.

Listening to these in succession, I started to feel the weight of Max’s reputation. I’m left with a sense of Max’s supreme excellence as a drummer. No matter what, he always sounds great. I was stunned.

Hearing him deal— in real time— with a complex Abdullah Ibrahim left-hand vamp on “Streams Of Consciousness”, play Cecil Taylor’s rhythms in their second set, co-exist with Braxton, test the limits of endurance with Shepp, or suggest a new concert music with Crothers makes it obvious: no matter the setting, no matter his agenda, Roach was always a master drummer.

Roach and Shepp made a live recording, The Long March (hatHut, 1990) at the Willisau Jazz Festival in August 1979, as did Roach and Braxton, One In Two, Two In One (hatHut, 1980), recorded the day after The Long March.

This is a fantastic series, I'm learning a ton.

Excellent analysis, Vinnie. I used to own 3 of the 5 duos you cover (missing the C. T. and the Connie Crothers and have both the Shepp and Braxton duos on hatHut –– amazing that those live sets were recorded in a 24-hour+ period). The two recordings by Mr. Roach and Mr. Braxton are among my favorites & the Shepp duo is pretty darned good.