On Oceans of Time

Billy Hart's musical autobiography is a must-read.

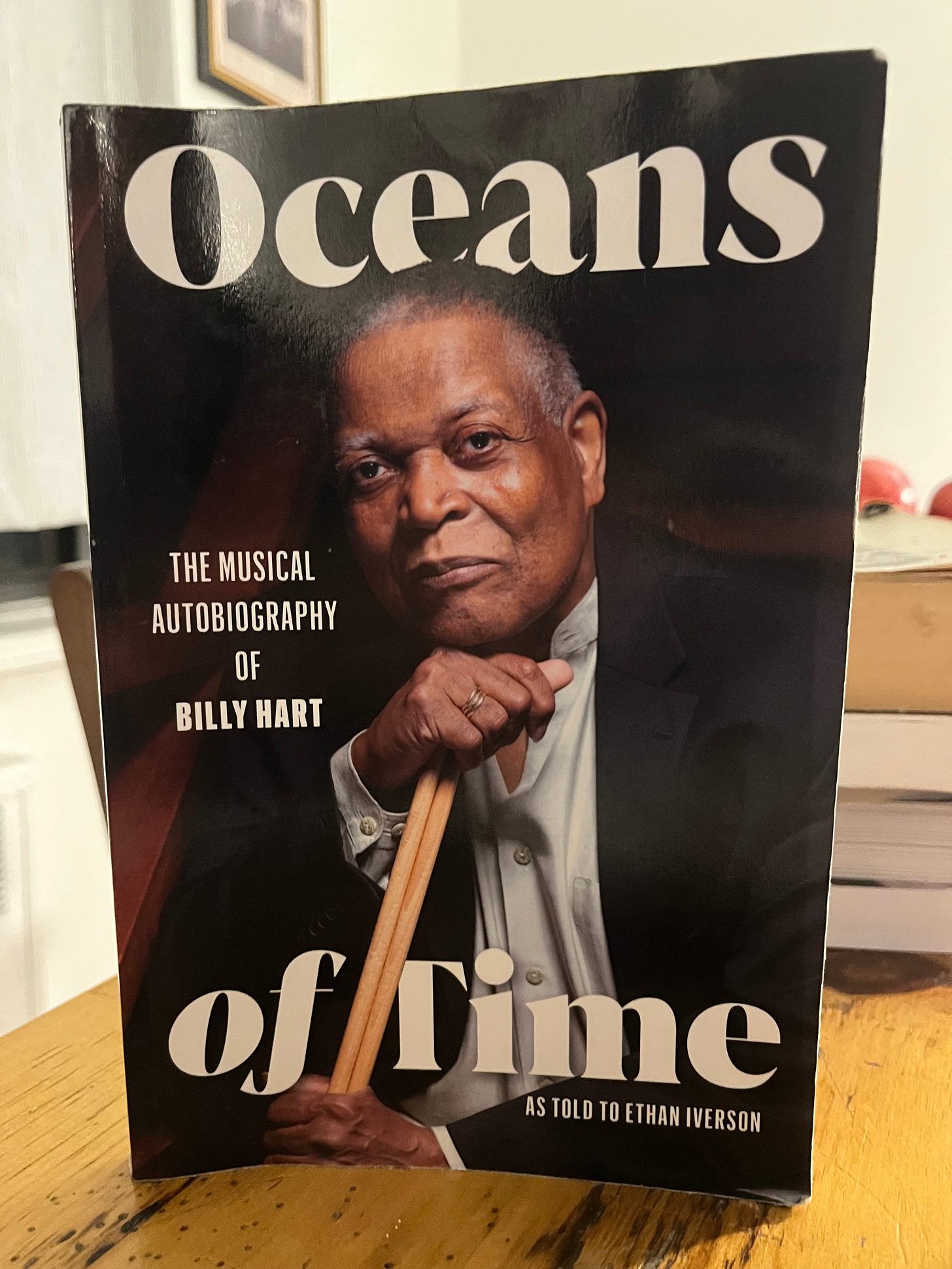

Tightly focused not on Billy Hart’s career (gigs, money, success, failure) but on the music itself— its meaning, its origin, what Billy learned, and how that informs what he’ll play today, at age 851— Oceans of Time: The Musical Autobiography of Billy Hart (Cymbal Press, 2025) is simply essential. I’ve never read a jazz book so devoted to the truth.

That makes the book sound like a weighty tome, when in fact it’s the opposite. Oceans of Time is a lot of fun, basically a readable version of listening to Billy Hart play a set or two at the Vanguard. The 162 pages goes down easy2— Hart speaks with a quiet, just-so poetry all his own (“When I hear Art Blakey now, I can appreciate that he was a piano player, someone who knew the music from a harmonic perspective”; “Mickey Roker’s cymbal beat had all that Caribbean information, plus something that could swing you to death”; “At first I was feeling pretty bad about losing another gig, but, again, it always helps to treat every event with optimism.”), the stories and thoughts unfold, the chapters fly by3.

For the most part, Oceans of Time is straightforward autobiography. But that description belies the complexity and richness of the text. Hart and his co-author, Mr. Ethan Iverson, gently but consistently underscore Billy’s story with the larger history of the music, deftly darting between eras, jumping in and out of Billy’s life. As the book goes on, Billy’s musical life becomes the story of jazz in miniature.

Page 27 is as good a place as any to see what I mean:

When I joined Jimmy Smith, I replaced Donald Bailey, who we called “Duck”. Elvin Jones gets the credit for making the drums more polyrhythmic, especially on the records with John Coltrane, but this was community music, where many people made an important contribution. Along with Edgar Bateman, Donald Bailey was one of the other innovative drummers bringing those kinds of polyrhythmic concepts into the music at the same time as Elvin Jones. There was some real African heritage in this approach.

Jimmy Smith made many classic records with Donald Bailey. When Duck plays the slow shuffle on “Midnight Special”, he plays the hi-hat on the upbeat with his foot. I still do that once in a while today, and when I do, it’s a tribute to Duck. I showed that beat to Grady Tate, and then Steve Gadd played it too. When I play that beat today, someone might say afterwards, “I heard you playing that Steve Gadd beat.” No. That is out of order. Steve might get the credit with the commoners, but the royal line goes back to Duck.

Duck didn’t like to fly, so he ended up quitting Jimmy Smith when Jimmy started getting more and more popular. Jimmy was picking up drummers on the road, and in Washington, D.C., he expected to get George “Dude” Brown. Dude was a great drummer, a deep swinger, and a bit of a character. Helen Hill told me about how George would get irritated with people who were making noise upstairs in his apartment building, and in retaliation would take out his gun and shoot through the ceiling.

Three tidy paragraphs that show a line from the drum language of the Sixties, to Hart’s multi-decade career, to cultural history, all underscored with the deeper human meaning of it all. There’s enough on this one page for a lifetime of study. Bravo Mr. Billy Hart!

Oceans of Time opens with a full-throated shout of righteous and joyful truth. On page one, paragraph one, Billy defines swing— “‘Swing’ is a musical system that causes joy, euphoria, and optimism.” You could stop reading right there and return to life enriched and broadened.

We then meet Billy’s family— his parents, brother Ronald, and beloved grandmother (for whom his tune “The Duchess” is named). Panning out to include neighbors and schoolmates, we see young Mr. Hart immersed in a multi-generational and aspirational community, for Hart’s family part of a dynamic social and professional scene in Black, pre-Brown vs. Board of Education Washington, D.C.

Billy’s first drumset arrives at age 13 (after pestering his mother, then petitioning The Duchess) at the same moment that his grandmother’s neighbor4 gives Hart a few Charlie Parker 78s5 : “Just Friends” b/w “If I Should Lose You” (Charlie Parker with Strings) and then “Au Privave” b/w “Star Eyes”, with Max Roach. This was the moment— a drumset, Charlie Parker, and Max Roach have conspired to enchant Billy Hart forever.

Soon, Hart’s venturing out and sitting in, meeting the DC jazz community. Here, Billy is explicit about not being at the head of the class, struggling mightily to connect with the more experienced musicians, even failing outright a few times. But Billy is an intellectual and optimist who loves jazz and learning, and he draws on both loves to keep trying. This is humility in action. With that approach, you can do almost anything.

Eventually, Hart connects with the musicians he most admires, including Buck Hill, pianist Reuben Brown, and Butch Warren, but most crucial is Shirley Horn.

“Shirley Horn meant the world to me, both personally and musically. She was somewhere between my first love and my grandmother.” Horn is a constant presence, her music and example always in the back of Hart’s mind. When Sonny Stitt shows Billy the importance of beat one at a fast tempo, Hart realizes that he already knew this from Horn— “That ‘one’ of hers went straight from the piano down to the center of the earth: listen again to “I’m Old Fashioned” from A Lazy Afternoon (SteepleChase, 1978)”.

In his late teens, Billy gains valuable experience playing with the touring rock and roll and R&B acts at the Howard Theater, but moves decisively into jazz when he joins Jimmy Smith in 1964. This was a major opportunity: Jimmy Smith was a high-profile, year-round touring gig, for which Hart6 turned down James Brown.

In late 1966 or early 1967, Billy, married and a father, joins Wes Montgomery, then touring with his brothers, pianist Buddy Montgomery and Monk Montgomery, jazz’s first electric bassist. When Wes dies suddenly in 1968, Billy, after being one of Montgomery’s pall bearers, decides to immerse himself in the NYC scene.

One thing, another thing, and then voila, Hart has a chance to record with Herbie Hancock7, who he’d known casually since 1962. Together with bassist Buster Williams, Billy is the foundation of Hancock’s Mwandishi band, perhaps the group with whom Billy’s most associated8.

Hart joined Mwandishi in the summer of 1970. By 1973, the group was history. Staying afloat, Billy spent the next year with McCoy Tyner, then several years with Stan Getz. By the early Eighties, Hart wasn’t a permanent member of an established leader’s group, or any group that worked year-round at a high level. From then on, “it would always be a struggle to assemble the patchwork quilt of gigs and tours”, a remarkably frank admission.

Somehow, Billy turned this situation to his advantage, using his freedom, precarious as it probably was, to immerse himself ever deeper in all that NYC jazz had to offer, all that the European touring circuit could provide. He’s nearly the house drummer for SteepleChase Records, joins a number of semi-permanent bands, the Dave Liebman/Richie Beirach Quest being the most notable example9, and forms his own groups, recording for Grammavision in the Eighties and Arabesque in the Nineties. It’s in this era (ca. 1977 to ca. 1997) that Hart sort of becomes the drummer we know and love.

Reading and re-reading Oceans of Time, I start to get it— though I’m sure the day-to-day was sometimes difficult, Billy held the line10; every year his playing, always wonderful, took on greater depth and meaning. Hart treated every gig as a chance to learn, looked at everything as a possibility, and kept growing. In the Nineties and Two Thousands, when the younger generation looked to Billy for mentorship, Billy was ready.

A natural student, a serious thinker always seeing parallels, connections, and reflections swirling around some central ideas11, Hart is a master teacher, a man in love sharing what he loves. The final chapter, on Billy’s teaching, contains everything anyone interested in learning about jazz drumming would ever need. As Hart writes, he avoids platitudes and tries to communicate the seriousness of the endeavor: “I never say ‘have fun’, or ‘it’s easy’.” Amen.

Throughout Oceans of Time, it’s clear that the story isn’t over. Billy’s upcoming release, Multidirectional (Smoke Sessions, 2025), featuring his longstanding quartet of Mark Turner, Ethan Iverson, and Ben Street, is just incredible, a snapshot of the band at the next level.

Billy was always multidirectional— his 4/4 swing implied astonishing freedom, his free playing implied straight-ahead swing, his even-eighth notes and backbeats implied shuffles; his Afro-Cuban playing suggested bebop. Now this concept has seeped into the entire group, and Hart is freer than he’s ever been.

The Billy Hart Quartet is playing next weekend at Smoke. Jazz goes on and on….

Actually, Billy doesn’t turn 85 until November 29th.

There’s an appendix where drummers talk about Billy, and I’m thrilled to be in there (talking about Billy’s album Oceans of Time); an appendix on Billy’s gear; and a user-friendly discography.

One or two people have mentioned that they read it one sitting, very easy to do.

The neighbor was tenor saxophonist Buck Hill, a key player in DC’s jazz history and soon a mentor to Billy.

Hart mentions that Hill didn’t need the Bird 78s because he’d gotten a new hi-fi stereo and the newly-issued Verve Charlie Parker LPs to play on it. I love this detail!

Billy writes that his first wife Dolores actually made this decision for him— Brown and Smith called asking for Billy, then living in DC, on the same day, and Billy was in California with Shirley Horn. It was Dolores who put off James Brown (!) with an excuse that she couldn’t reach Billy, and then called Billy and told him about Jimmy Smith.

Hancock and Hart first appear together on Joe Zawinul’s Zawinul (Atlantic, 1971).

Victor Lewis had his life changed forever after witnessing a Mwandishi concert. See pages 193-196 of Bob Gluck’s You’ll Know When You Get There: Herbie Hancock and the Mwandishi Band to get the full effect.

Other semi-regular gigs for Billy included Marc Copland; Hank Jones; Joe Lovano; Tom Harrell.

Chapter 13, a series of thoughts and attitudes centered around swirling around Max Roach, gives the best sense of just how deep-bone Billy’s commitment is. This is the part of the book I return to most, so profoundly does Billy understand Max, and by implication, what jazz drumming and the drumset are really about.

Some of these might be— swing is a musical system; all jazz is in 2 and 3 at the same time; the clave connects all American traditions, North, Central, and South. Et cetera.

Billy joined Jimmy Smith in January 1964, not 1963. It's likely that Billy joined Wes Montgomery toward the end of Spring 1967.

I loved this book and honestly can’t wait to read it again: so refreshing to have the book focused on the music as opposed to extracurricular stuff