There Comes A Time: Tony Williams in 1980

His final fusion session shows one era coming to a close and another beginning.

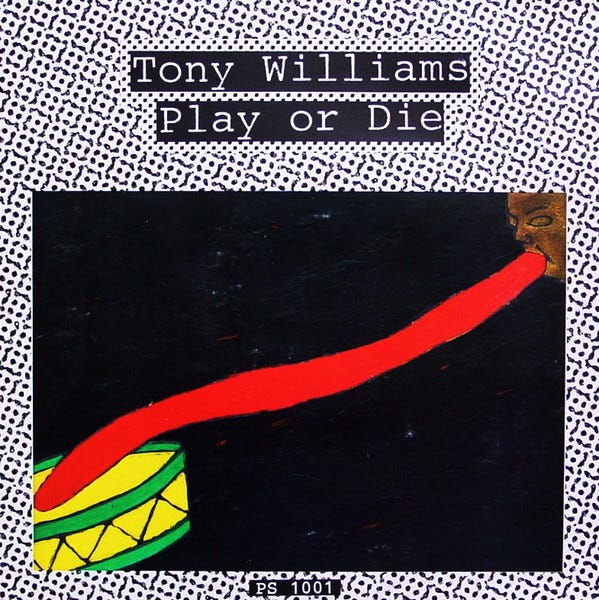

Play Or Die, the 1980 trio date of drummer/composer/bandleader Tony Williams accompanied by keyboardist Tom Grant and bassist/keyboardist Patrick O’Hearn, has long been the single most obscure item in Tony Williams’ discography. I first learned of Play Or Die as a college student from my teacher, Mr. John Riley, but didn’t hear the album until many years later, after which I felt like a drum archeologist back from a field expedition, telling other drummers that yes, it does exist, I held it in my hands and listened to it.

Thanks to the efforts of Tony’s widow, Colleen Williams, Play Or Die has finally been properly reissued, with improved sound, correct personnel, corrected song titles, and re-assigned composer credits.

Play Or Die isn’t the raw, aggressive Lifetime of the Young/McLaughlin years, or the psychedelic soul of Tequila-era Lifetime, nor is it the stone-cold killer Allan Holdsworth Lifetime. Instead, Play Or Die is a drum-centric, keyboard-driven, New Wave-inspired summary of all that Williams had learned since venturing into the electric unknown in 1969, and, rather subtly, a sneak preview of Williams’ new musical goals as the Eighties dawned.

When 1980 rolled around, an astute observer might have wondered if the fusion movement, of which Williams is a primary author, was wrapping up. At the time, Dexter Gordon and Woody Shaw were Columbia Records artists with large audiences, but they might have seemed an anomaly. In the spring of 1980, however, the great Wynton Marsalis, then 18 years old, began his jazz career when he joined Art Blakey. By 1982 he would be touring with Williams in VSOP II and a Columbia recording artist in his own right.

Marsalis’ ascent placed him in a position to be the media representative and spokesperson for a young cohort of brilliant musicians, dubbed the Young Lions. Their music was noted at the time for its return to the sound of classic jazz from the Fifties and Sixties, and was seen as a repudiation of fusion, and by extension, its practitioners. But scratch the surface, and we realize that the Young Lions, far from repudiating fusion, had actually repurposed it. Especially in the rhythm section, the Young Lions were, in a sense, acoustic fusion.1

Play Or Die is a glimpse of Williams’ thinking between The Joy Of Flying, his 1979 all-star Columbia release, and Foreign Intrigue, his 1985 acoustic, swinging re-emergence as a bandleader on Blue Note; we can hear how Seventies fusion very gradually gave way to Eighties acoustic modern jazz. On Play Or Die, one can feel Williams signing off on his fusion days, joyously and raucously summarizing everything he’s learned while hinting at his interest in older rhythms and more traditional forms.

It’s sort of the Star Trek VI of the whole Lifetime era; Williams makes his joyful noise one more time for the world, nods towards the present day, notices that a time has come for a change, and peaces out.

The road to Play Or Die was a bumpy one. The ‘original’ Lifetime—The Tony Williams Lifetime— of Williams, organist Larry Young, and guitarist John McLaughlin released a brilliant debut album in 1969, recorded a follow-up in 1970 with ex-Cream bassist/vocalist Jack Bruce on a few tracks, toured the US and England; and then splintered. Various other Lifetimes from 1971 to 1978, sometimes with singer Laura “Tequila” Logan, often with the legendary guitarist Allan Holdsworth, continued the same pattern— brilliant records, unforgettable shows, disbandment.

By 1979, Williams had chased the sound of Lifetime to The Joy Of Flying, his final Columbia LP on which he’s heard in no less than three different all-star fusion combinations (duo with Jan Hammer; quartet with Herbie Hancock, Tom Scott, and Stanley Clarke; quartet with Jan Hammer, George Benson, and Paul Jackson), plus a straight-up rock instrumental with guitarist Ronnie Montrose, and as a wild card, a beautiful duet with Cecil Taylor, one that should be more widely-known.

Pressingly, The Joy Of Flying was a success, putting Williams back in the commercial mainstream. Though it featured no specific ‘Tony Williams’ or ‘Lifetime’ band, and, most egregiously for Williams, none of his own compositions, the demands of a hit record must be satisfied. So, when a tour in support of The Joy Of Flying was booked, a new Tony formed a new group, this time a quintet featuring guitarist Todd Carver, bassist Bunny Brunel, and keyboardists Bruce Harris and Tom Grant.

Tom Grant was living in Portland, OR in 1979, where he had a local rep for touring gigs with Woody Shaw, Joe Henderson, and Charles Lloyd. He got an out-of-the-blue call from Tony Williams, who hired him over the phone2. The group toured Europe that summer of ‘79, which resulted in some fine concert footage, found here.

After their tour, Williams disbanded the ‘Joy Of Flying’ group, but retained Grant for a new band. Grant then recommended bassist Patrick O’Hearn, a Portland OR native who had recently finished two years with Frank Zappa, and the final Tony Williams fusion band was complete.

In May 1980, the trio of Williams, Tom Grant, and Patrick O’Hearn headed to Europe for its only tour; at the end of the tour, Play Or Die was recorded. According to the liner notes, only 500 copies of Play Or Die were printed, which would make the two or three copies I saw in the 2000’s rare records indeed. At some point in this period Williams’ contract with Columbia was canceled; were complications arising from a canceled record contract a contributing factor to Play Or Die’s obscurity?

Regardless of the record business machinations which might have been afoot, Play Or Die is an unfairly obscure session. Tony sounds great, is in wonderful form, and while Mr. Grant and Mr. O’Hearn play excellently and hold their own, they seem selflessly more interested in hooking up Tony than in soloing. O’Hearn and Grant each take some great solos, sure, but they seem uniquely content with setting up The Master.

The overall sound of The Joy Of Flying, especially the duos with Jan Hammer, is a direct predecessor to the keyboard-driven tones of Play Or Die3. Also in the mix is New Wave pop-rock; Grant’s keyboards give the music a distinct Eighties pop tinge, while Patrick O’Hearn would soon be a member of early-MTV faves Missing Persons. But underneath all this, Tony seems interested, for the first time in a long time, in playing some jazz drums.

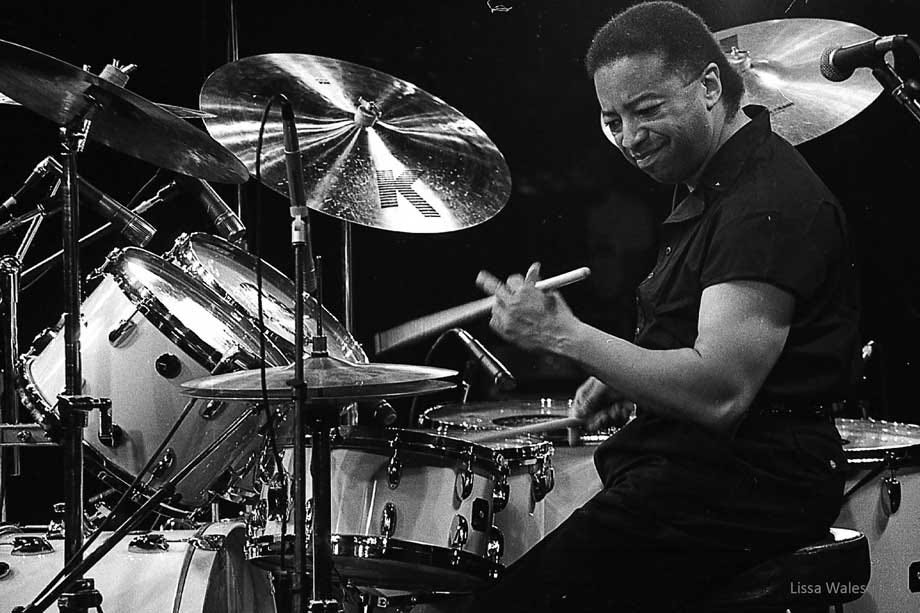

On album opener “The Big Man”, composed by O’Hearn, the first percussion sound we hear is Tony’s ride cymbal. Tony’s ride cymbal is one of the defining sounds of jazz, as classic as muted Miles, Monk’s left hand, or Duke’s sax section; that sound is Williams’ signature, and is a synecdoche of jazz itself. This is big— this is the first time a Tony Williams album has featured his signature sound so prominently, center frame, up close. Tony’s right hand on his ride cymbal, swinging at a medium tempo, in an electric context, is building a bridge from the 1970’s to the 1980’s. Welcome home.

Williams is practically luxuriating in the support he’s getting from Grant and O’Hearn, as he shuffles, solos, swings, sets up the melody, deploys his signature licks, and mixes it up with Grant. We can almost hear him smiling.

“Beach Ball Tango”, another O’Hearn tune, begins with Tony unaccompanied, invoking the Elders, asking for a great take. They give him one. The up-tempo 4/4 rock beat and surf-rock melody creates a ‘new retro’ sound that is pure New Wave, not far from Joe Jackson, Blondie, or The Cars. There’s a hint of samba on the bridge, before Grant and Williams dialogue. The out head spirals into a drum solo, and Williams’s single stroke roll is a celebration of life.

“Jam Tune”, credited to Grant, O’Hearn, and Williams, was called “Spencer Tracy” on the original LP. Tom Grant stated in a recent interview that it was a jam, not a tune they had in their book. Perhaps he means it was a tune they put together in the studio, because it’s not a one-chord jam. Instead, there are three discrete sections, each with its own melody. There’s a cowbell overdub on the B section, and Williams even goes for a Steve Gadd beat in the C section— the teacher is copping from the student. In another universe, this cut would have made a great backing track Cyndi Lauper.

“Para Oriente” was a recent Williams composition, featured often in this period, with Trio Of Doom and VSOP. (Later, this tune was re-worked into “Angel Street” for the Tony Williams Quintet.) O’Hearn gets his first solo on the album, but the big reveal is the walking bass in medium 4/4 swing, a sound Williams had never before featured on his own records 4. As Grant plays some choice phrases, beautifully hooking Tony up, the bridge from Seventies fusion to Eighties modern jazz starts getting some traffic.

The album ends with Williams’ classic “There Comes A Time”. First heard on 1971’s Ego, the third album by The Tony Williams Lifetime, where it had pride of place as the opening track,5 the song has long been recognized as a classic.

The lyrics to “There Comes A Time” are certainly the best lyrics Williams ever wrote, a series of phrases about one era coming to a close at the exact moment another is beginning. None other than Questlove recently devoted a few pages to this song in his recent, important book Music Is History, where he singles out Williams’ line “I love you more when it’s over” as describing not just a personal feeling, but a sense of history itself, how time moves and change comes, whether we accept it or not.

The melody of “There Comes A Time” floats above the earthy blues tonality of the bass line, and while both the bass line and the melody (a sort of C# minor pentatonic, with an added A natural) are, individually, relatively simple, when combined, they create brief, disturbing dissonances, with many minor 9ths and major 7ths. The ‘cracked 5/4’ (Questlove’s description) swing feel of the song perfectly captures the unsettled, moving-on mood of the lyric, melody, and harmony.

Tony plays a great drum solo at the end of the track, but his vocal performance of “There Comes A Time” on Play Or Die is astonishing. Somewhere along the way he’d become a great singer. Unlike the original Lifetime, where his singing is often a matter of taste (I’ve always loved it), here he simply sounds great, controlling the pitch, delivering the song. There is even a new interlude between the verses, with Tony’s voice overdubbed, a la Stevie Wonder, further evidence of how much he’d progressed as a singer. Strangely, he never sang again on a record.

He seems to be saying, or singing, Ok, I learned this. This is my song and my band. And that’s enough for now. In this context, “There Comes A Time” is a song of goodbye to jazz/rock, Lifetime, fusion, Columbia record deals, and Tony’s dream of an electric, jazz-based music for a mass audience. I’m speculating, of course, but it makes a good story and it fits with the facts.

Play Or Die in May 1980 was truly the end of the road for Williams the fusion musician. There were guest spots on albums by Santana, Allan Holdsworth, Jack Bruce, and others, just enough to keep his fusion credentials validated, but his music had moved on. His years of musical study and personal growth, starting with his move from NYC to the Bay Area, in 1977, began bearing fruit in 1985 with the aforementioned Foreign Intrigue project for Blue Note.

Of course, out of Foreign Intrigue came the Tony Williams Quintet, featuring Wallace Roney and Mulgrew Miller, which became the new vehicle for Tony’s compositions and drumming. Releasing a string of well-received Blue Note albums, the Quintet lit up sell-out crowds at clubs, theaters, and festivals from 1986 until roughly 1993. For long-time Williams observers, it was satisfying and heartening to see him enjoy his success, finally receiving the large audience, critical accolades, and regular band he had so long sought and deserved.

Tony Williams’ musicianship and commitment to his craft were apparent when he was 17 years old, playing with Miles Davis; his lifelong commitment to personal and musical growth should be more widely known. With its subtle hints at first principles— 4/4 swing, walking bass lines, the ride cymbal— Play Or Die is almost Williams’ first album of the coming new era. Altogether, it’s an astonishing and thrilling document, made all the more potent by its modesty as by it perspicuity.

I am going to be exploring this fusion/young lion connection extensively in future posts. When wondering “what happened to fusion?”, listen to the rhythm sections of the Young Lions records. We are overdue in recognizing the incredible contributions of Mulgrew Miller, George Cables (older than the Young Lions, but a godfather to the whole scene), Donald Brown, James Williams, Charles Fambrough, Charnett Moffett, Marvin ‘Smitty’ Smith, Ralph Peterson, Jeff “Tain” Watts, and many other rhythm section giants of the 70’s, 80’s, 90’s. Their re-working of fusion and avant-garde techniques in a ‘straight-ahead’ context laid the groundwork for the endless possibilities in jazz today.

Grant had actually been recommended to Tony by guitarist Todd Carver, who in turn had been recommended to Tony by Jeff Lorber!

Williams had played on three tracks of Weather Report’s Mr. Gone in 1978, and the title track, featuring Williams swinging with Zawinul, sounds a lot like Play Or Die.

True, the track “The Old Bum’s Rush” from the album of the same name, is 4/4 swing, but the track is obviously a minimally-organized blues jam with no composed melody.

“Clap City”, track 1 on Ego, is really a prelude to “There Comes A Time”

Great find; thanks for posting [I never even knew OF this record]

Speaking of Tony's ride cymbal, what do you think of the 1996 'Arc of the Testimony', Bill Laswell's electric concerto for Tony? (excellent 2021 24 bit remaster by M.O.D. Reloaded)

Tony Williams did a few gigs with Jan Hammer again in 1991 or thereabouts. There was a Down Beat review (or maybe it was Musician?) but no record came of it. I think I have a boot of one of them somewhere.