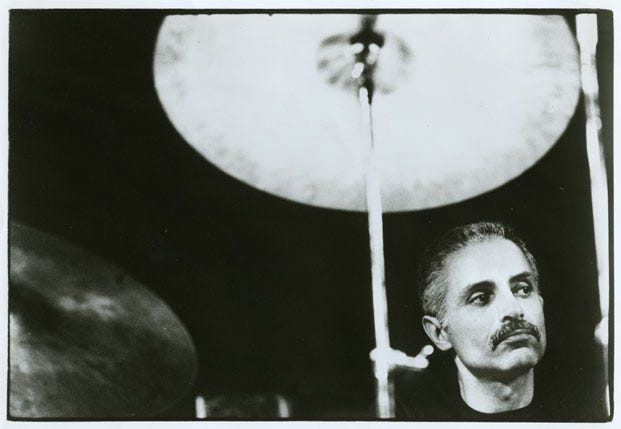

Turns: Paul Motian, 1963-1965, part 2 of 2

On the edge with Carla Bley and back home with Mose Allison

In my last post, we took a detailed look at Paul Motian’s earliest foray into the new jazz of the 60’s, released on Paul Bley With Gary Peacock, and how he applied the new ideas to his gig with Bill Evans, documented on Trio 64.

In this essay, we’ll explore Motian’s innovative playing on Paul Bley’s Turning Point. I’ll attempt to place that album within the context of the rapidly-evolving jazz of the mid-60’s. I’ll finish this essay with a listen to vocalist Mose Allison’s Wild Man On The Loose, on which Paul Motian’s mature voice- a blend of the deepest bebop, free jazz openness, and something entirely his own- is heard in full flower.

I’m hoping my comments on the music get you to listen to these records right away, especially Wild Man On The Loose, which should be more widely heard.

PAUL BLEY with JOHN GILMORE, GARY PEACOCK, PAUL MOTIAN: TURNING POINT (IMPROVISING ARTISTS, IAI 37.38.41) Released in 1975.

Mirasound Studios, NYC, Monday, March 9th, 1964. Paul Bley, piano; John Gilmore, tenor sax; Gary Peacock, bass; Paul Motian, drums.

Turning Point is a bold, mysterious document. It was released on Paul Bley’s Improvising Artists label in 1975, the height of the fusion era, nine years after it was recorded.

Consisting of five tracks by a quartet of Paul Bley, tenor saxophonist John Gilmore (of Sun Ra), Gary Peacock, and Paul Motian1, plus three tracks from another, later session (minus Gilmore and with Billy Elgart on drums), and featuring Carol Goss's acid-cartoon cover art, Turning Point seems ahistorical, outside time, willfully obscure.

No other recordings were made by the quartet of Bley-Gilmore-Peacock-Motian. The only other document of this group is a written account from Paul Bley’s autobiography:

One cold February [1964] in the Village, I got a phone call from Gary Peacock. “Paul, I’ve got a gig at the Take 3 [on Bleecker St in Greenwich Village, a ‘coffee bar theatre’ where Cecil Taylor also played] for two bands. You and I will play in both bands. One band will have John Gilmore and Paul Motian, and it will be followed by a band with Albert Ayler and Sunny Murray. It starts on Friday. It pays five dollars [roughly $50 in 2022] a night.”

“Fine”, I said. “I’ll take it.”

-Paul Bley with David Lee, Stopping Time, 1999, page 87.

Starting in 1962, the bulk of Paul Bley’s repertoire was composed by his then-wife, Carla Bley. Carla’s earliest music consisted of short, highly detailed, and wildly suggestive themes; pieces like “Donkey”, “Walking Woman”, “Ictus”, and “King Korn” are like coiled springs, just waiting to be sprung into improvisations. The biggest challenge for Paul Motian? Carla’s music, equally indebted to Count Basie and Anton Webern, implied a new rhythmic concept- no steady time.

It can be hard to grasp just how revolutionary an idea this was in winter 1964, when Turning Point was recorded, the Beatles arrived in the USA, and the Civil Rights Act was on its way to the US Senate.

For instance, Ornette Coleman’s late 50’s and early 60’s music, the absolute standard for newness in jazz, then and now, always used a steady beat, was never rubato or ‘out of time’ (at least not for a whole tune). Coleman’s drummers, Billy Higgins and Ed Blackwell, were two of the most swinging drummers in history. They were geniuses and innovators who connected Ornette to jazz’s deepest past while simultaneously suggesting the outer reaches of jazz’s future.

So, Billy Higgins and Ed Blackwell couldn’t be the model for Carla’s music as played by Paul Bley, Gary Peacock, and John Gilmore. Strong, swinging drums would only tie down her melodies.

Sunny Murray had created a jazz drum vocabulary without a steady beat on Cecil Taylor’s At Cafe Montmarte from 1962, perhaps the first full-length jazz album to dispense with steady time. Throughout, Murray plays accelerating and decelerating rolls on the cymbal and snare, nervous shivers on the bass drum and hi hat, and follows the contours of Jimmy Lyons and Cecil Taylor. Perfect.

However, Carla’s melodies were highly detailed, explicitly referencing bebop and other older styles. Sunny Murray’s waves and currents might obscure the nuances and pearls in Carla’s tunes. The only conclusion: Carla Bley’s2 music, as played by Paul Bley and Co., required an as-yet unheard approach to the drums.

The history of jazz isn’t necessarily the history of jazz on record. New York musicians reacted to changes in the music in real time, and we can assume we’re missing big pieces of the puzzle.

Still, on Turning Point, Paul was a pioneer, ahead of his time by being able to leave time behind, an approach that allowed Carla Bley's music to live on its own terms. In March 1964, Milford Graves (Motian's junior by a decade) had yet to record3, Rashied Ali and Beaver Harris wouldn’t be making waves in New York for another two years, Andrew Cyrille was playing relatively straight ahead music with Walt Dickerson, and Barry Altschul was just getting noticed. Even Albert Ayler’s epochal Spiritual Unity, with Peacock and Sunny Murray, was 4 months in the future.

Paul, just a few days shy of his 33rd birthday when Turning Point was recorded, was older than not just Milford Graves, but Rashied Ali, Beaver Harris, Andrew Cyrille, J.C. Moses, Sunny Murray, and Barry Altschul. He was the elder, out in front, with his own sound and vocabulary for the new, tempo-optional environment.

Motian learned to play Carla’s melodies on the drums, and this, I think, is the beginning of his mastery of rubato. I suggest that Paul’s breakthrough in the new music happened when he played the melody of an abstract composition on the drums, then focussed on that melody while playing with the group. Let’s hear from Paul and Keith Jarrett:

“If I’m playing a solo on a tune, I’m following the form or melody of the tune. With free music, as with my tunes, there’s a form, but its more abstract. Usually there’s a melody I’m playing off of, but it’s not a specific number of bars.”

“I still think about the melody. There’s got to be something there to play off of. You’re not going to be out in the air playing just anything. If it’s a song, you play the song. If it’s a melody, you play off the melody. If there’s no melody, there will still be a form to play from. Maybe some of the stuff I’m playing sounds chaotic, but it’s not.”

-“Paul Motian: Nice Work If You Can Get It” by Ken Micallef, Modern Drummer, June 1994.

“Of all the drummers I’ve worked with, not a single one was more sensitive to melody than Paul”.

-Keith Jarrett to Neil Tesser, liner notes to Keith Jarret- Mysteries: The Impulse Year, 1975-1976

Somewhere in the swirl of all five tracks on Turning Point , Motian explicitly plays and references the melody of each piece, as well as the melodies of the soloists. Specifically, his playing on the melody of “King Korn” is a glimpse of the future.

This is the foundation of Paul’s fully-developed voice; Paul Motian will honor the melodies of every composition and every player for the rest of his life. Let’s listen.

1.) Calls (Carla Bley) Motian is playing louder and faster than before; the straight man no longer, he’s now a full partner in the improvisations. The tempo never quite departs, and Motian plays the simple theme behind the soloists a few times.

2.) Turns a.k.a Turning (Paul Bley) After the melody, the tempo melts away and returns, over and over. Motian’s cymbal interjection early in the piano solo and dialogue with Gilmore show his new confidence.

3.) King Korn (Carla Bley) This is the first melody in the Paul Motian discography that could truly be said to be out of time, rubato, or free tempo.

Carla’s perfect composition was originally intended for Sonny Rollins. Motian plays the melody in unison with the band, and his playing of that melody is full of detail, shade, and nuance. Let’s linger with this track for a moment.

If you could hear an edit that was just the drum track, you could still tell it was “King Korn”. This incredible feat of drum orchestration is all the more impressive considering that there’s no steady beat!

Just as Max Roach, Art Blakey, and the other masters of the 1940’s translated the new jazz language to the drumset, now Paul Motian has done the same with (one of) the new jazz languages of the 60’s.

Motian is precisely and meticulously translating the melody of “King Korn” to the drums, thus laying a foundation for his later mastery of out-of-time music, as a composer, bandleader, and drummer. Paul Motian’s future is on this track for all to hear.

Still, after the melody, as the piano solo starts, tempo is back in the conversation. But Peacock and Motian are aligned outside time for Gilmore’s incredible solo. Paul’s fill just before the out head…… every time I hear it…. “WHAT??!!??”

4.) Ictus (Carla Bley) The most aggressive, least tempo-implied piece in this set. Paul’s ideas are coming from “broken time”, he cadences with the soloists as he ventures ever further from time-keeping patterns. Motian might almost be mistaken for Milford Graves, who had yet to make a recording.

5.) Ida Lupino (Carla Bley) A timeless Carla melody. “Ida Lupino” is the closest to straight time heard on this session, and Paul obliges with some uncharacteristic 16th note fills throughout. Are the straight eighth notes here the earliest instance of the “ECM feel”?

Though Turning Point is little more than a glimpse4, we’re fortunate this music was documented at all. Though the Bley-Gilmore-Peacock-Motian quartet was a short-lived unit, playing together for perhaps a few weeks that winter of '64, there was an entire movement building behind these sounds, with young players, new bands, and even a label (ESP-Disk) to record and release the music. As even a cursory read of Amiri Baraka’s Black Music will show, however, there was little steady work for any of the players in the new style.

“I played with Carla and Paul Bley, Albert Ayler, and John Gilmore…. I think that 1965 was one of the good periods in New York. That was around the time the Jazz Composer’s Guild was organized. I was playing a lot but I wasn’t making any money. I used to work for two dollars a night. That was it. That went on for a couple of years, but I managed.”

-Paul Motian, quoted by Scott K. Fish, Modern Drummer, April-May 1980.

Though it was ultimately a great development for jazz, infusing the music with a spirit of creativity and social engagement that continues to this day, the new jazz of the 1960s, coupled with the rise of the Beatles and the rock-fueled youth movement, made it harder for many jazz musicians to find steady work.

It was in this climate that Paul Motian, always a survivor, got a gig with the popular pianist and vocalist Mose Allison5. One way to track the changes of the times is to watch Mose Allison and Paul Motian. In 1959, they were playing together with Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, but by 1965 they were playing Mose’s rock-adjacent songs.

Allison was then on Atlantic Records, an important label of the period, and was popular with both the young British rockers (Pete Townshend, Van Morrison, John Mayall) and the young American rock songsters (Leon Russell, Bonnie Raitt, Randy Newman), several of whom covered Allison’s songs. “Young Man Blues”, for instance, from the Who’s Live At Leeds, is a Mose Allison song.

MOSE ALLISON: WILD MAN ON THE LOOSE (ATLANTIC RECORDS, SD-1456)

Atlantic Studios, NYC, Tuesday, January 26 and Thursday, January 28 1965; Mose Allison, voice and piano; Earl May, bass; Paul Motian, drums. Produced by Arif Mardin and Neshui Ertegun. Released 1966.

While not in any jazz history text, this album was an unexpected joy to explore.

Some of what makes a drummer a great singer/songwriter drummer is hard to explain. On this album, I hear Paul achieve a goal most drummers find elusive: unique, distinct choices which enhance the music without pulling focus from the singer, songs, or musical big picture; call it the Jim Keltner, Connie Kay, or Shelly Manne tradition.

Paul never sounds ‘polite’ or ‘merely professional’ here. I speculate, based on how great the record is, that Paul was very into it. Nor does Motian sound like he’s musically compromised; indeed, he’s bringing many innovative ideas from his avant-garde experience to Mose’s date, demonstrating yet again the artificiality of categories like ‘free jazz’ and ‘jazz singer’.

1.) Wild Man On The Loose (Allison) Ramsey Lewis, boogaloo, a little New Orleans, and something mysterious and classical from Mississippi native Allison. In the recurring theme for this session, Paul has found a way to break up the time and assert his identity without getting in Allison’s way.

2.) No Trouble Livin (Allison) Pop jazz, loose and cool. Paul sounds A LOT like Kenny Clarke during the piano solo.

3.) Night Watch. (Allison) Even while keeping time in the simplest manner, Paul is a free agent with the tiniest details- surreal left hand brush sweeps that start and stop, occasional half notes on the cymbal where one would expect quarter notes, and so on.

4.) What’s With You (Allison) Allison is just slightly edgy- a bit satiric, sometimes just sarcastic, and definitely comic. Perfect for Paul! The beat on the piano solo is almost heavy.

5.) Power House (Allison). Again, the tiny details tell the whole story. The hiccups and pauses in the cymbal beat, the buzz stroke on the small tom, the occasional slightly surreal emphasis on downbeats, some cadences that are almost sighs or exhalations- all these details create the creeping sense that this drummer will simply not be doing business as usual, no matter what.

Paul is using what he learned playing with Gilmore, Bley, Peacock, Pharoah Sanders, and other free jazz luminaries to enhance Mose’s record date. He has expanded.

More than any other track on this album, I can picture Paul Motian playing like this at a gig in the 90’s or 2000’s.

6.) You Can Count On Me To Do My Part (Allison) Paul’s brushes, subtly changing patterns, fit the mood of the song, the tone of Mose’s voice, and Mose’s delivery perfectly. Mose was left-of-center, but still widely accepted, just like Paul. This is textbook “singer drumming”.

7.) Never More (Allison) Paul couldn’t play any more simply than he does on this track- quarter notes on the snare drum. Is Mose quoting the Raven?

8.) That’s The Stuff You Gotta Watch (Buddy Johnson) An early R&B classic, and the only song I know of recorded by both Paul Motian and Levon Helm. Naturally, Paul never plays an exact shuffle, but he comes pretty close for a few seconds.

9.) War Horse (Allison) Up-tempo, almost a Max Roach tempo. Motian doesn’t play the ride cymbal pattern for more than a bar or two during the piano solo; instead he mixes it up with half notes, the overall effect almost Afro-Cuban, very swinging. He bears down during the bass solo with more conventional time keeping, before the highlight of this entire survey: the first ‘Paul Motian drum solo’ on record.

There couldn’t be a more fitting audio end to this survey. Nothing he played with Bill Evans or Paul Bley sounded like this. It’s an almost-free jazz drum solo (and a chorus of traded 8’s) in an almost-pop jazz context. (That combination- almost free-jazz combined with almost pop-jazz- is a fair summary of Paul’s contribution as a leader and composer!)

It’s all here- the ‘childlike’ abandon (an illusion- no child could play a drum solo of such detail), a celebration of texture, color, rhythm, and contrast. This is the drumming and music that he became celebrated for, and here it is, in full flower at last, in the last place I looked for it.

“I played what I heard and tried to fit in... I never thought of playing that way. I’ve never pre-thought anything. It seems like it’s something that’s happened through my involvement with the music and the musicians. I think it was something that just happened.”

-Paul Motian, quoted by Scott K. Fish, Modern Drummer, April-May 1980.

Two years later, Motian would take part in the first recording session led by the young, virtuoso pianist from Charles Lloyd’s band, Keith Jarrett. It was Jarrett who paired Paul Motian with Charlie Haden. Haden took Paul even further into the new music; with Keith, with Haden’s own Liberation Music Orchestra, with Dewey Redman and Don Cherry; with Geri Allen.

Keith Jarrett encouraged Paul to compose; Keith sold Paul his childhood piano; he arranged for Paul to record as a leader, for the first time, for ECM. Eventually, Motian formed his own bands, took them on the road, and continued recording; he recruited then-unknowns Bill Frisell and Joe Lovano for his band in 1981 and they were a team for the rest of his life.

He wrote and recorded his songs, he formed new bands with young players, and went on the road; he collaborated with anyone who passed muster. Later, he stopped touring, played only in New York, and recorded a lot. He died in 2011, the legendary master from the beginning of the essay.

He left behind his music, the players he helped, and the effect his music had on those who heard it. None of this was fated, it was all his choice; in 1963, ’64, and ’65 he started turning, started choosing.

An extra special thank you to Ethan Iverson for his invaluable advice and encouragement……VS 11/14/22

An LP of the complete quartet session (two additional titles and a second take of “Ida Lupino”) called Turns was released by Savoy in 1987 and is not on YouTube or any other streaming service as of October 2022. Was the session of March 9th, 1964 originally a Savoy Records session?

“My personal favorite, definitely”- Carla Bley on Paul Motian, in conversation with Ethan Iverson, 2018. Read the whole interview here.

Mr. Graves’ first recording session seems to be Paul Bley Barrage, recorded October 20, 1964. Compare “Ictus” on Barrage with “Ictus” on Turning Point. Graves’ legendary sessions with Giuseppi Logan and The New York Art Quartet were on November 11 and November 26, 1964, respectively.

Motian participated in another Paul Bley-led session with the same quartet instrumentation as Turning Point. On May 25, 1964, Bley, David Izenzon, Motian, and Pharoah Sanders entered a New York studio for a session first issued in 2012 on an invaluable Pharoah Sanders retrospective called In The Beginning (ESP). The session yielded only 18 minutes of issued music, the most cohesive of which is a fairly brief reading of “Ictus”. Perhaps extra-musical factors kept this session from being completed. As we might expect, the music merely reinforces our impression of Paul Motian on Turning Point.

Allison had previously hired Motian and Henry Grimes for his June 1960 sessions for Columbia, issued on I Love The Life I Live and Mose Allison Heads For The Hills.

Too notch! 4 albums that I love but hadn’t thought about together, and will now never be able to hear without thinking of the others. This is what I’m looking for in great criticism: taking texts that I know and persuading me to hear them in a new way. *****

Yes!!!