Was Pete La Roca The First Free Jazz Drummer?

A two-minute drum solo on a 1959 Jackie McLean record had bold implications.

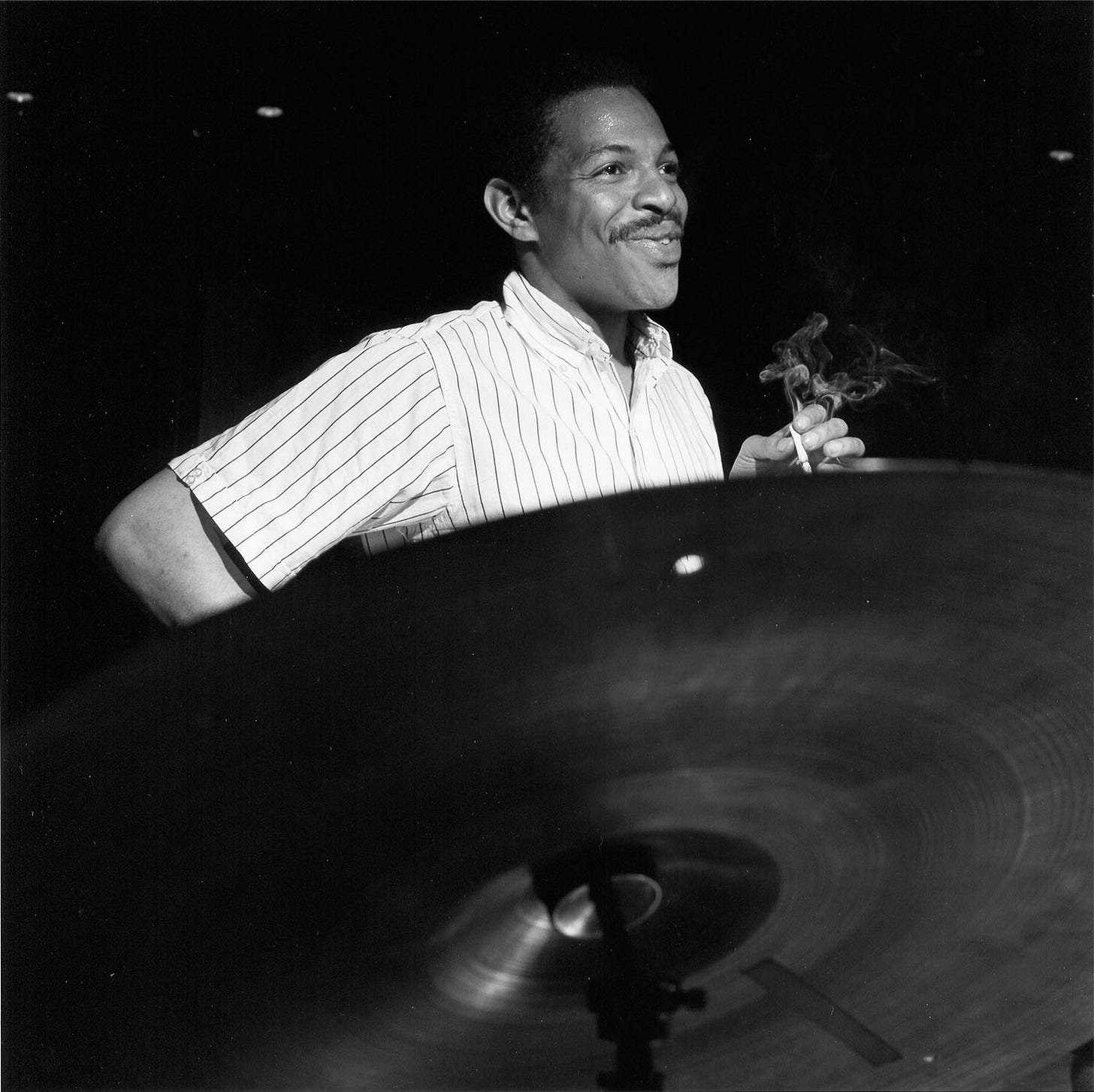

Drummer Pete La Roca’s solo on “Minor Apprehension”, the second track on Jackie McLean’s 1959 Blue Note release New Soil, is two minutes of brilliant, unaccompanied free improvisation. There’s no steady pulse, no reference to the 32-bar form, just an impression of the melody, using rhythm and sound to get that impression across. It might be the first recorded drum solo to take such liberties, which makes the solo, in effect, one of the earliest recorded examples of free jazz.

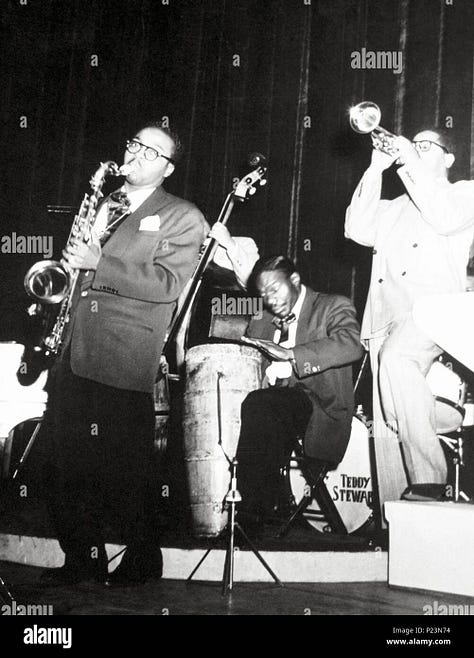

I’d long heard about the solo, thanks to writers Ken Micallef, Nate Chinen, and Stanley Crouch. I know of no other jazz drumming like this in 1959. However, La Roca’s first gigs were as a percussionist in Latin conjuntos, and it is Afro-Cuban drumming which is the main inspiration for La Roca’s solo. The intros, fills, and solos of Latin timbaleros and congueros like Tito Puente, Ray Barretto, and Mongo Santamaria paved the way for La Roca’s fantasia.

Pete La Roca on “Minor Apprehension” is using the music and rhythms of Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic to create new possibilities for jazz drumming, showing the deep African roots and common African heritage shared by ragtime, son, swing, clave, bebop, and mambo.

This is big; La Roca is playing a new way- so new that producer Alfred Lion reportedly had a fit of consternation as La Roca was playing- but using Afro-Cuban rhythms, some of the oldest and most powerful rhythms known.

Of course, two minutes of chopped and screwed Afro-Cuban rhythms played on a drumset at a late 50’s hard-bop record date is not, and cannot be, the beginning of free jazz, important though the solo is. Ideas don’t spread that way. But acknowledging La Roca’s innovative solo helps form a more complete picture of the emergence of free jazz in the mid-20th century.

Most importantly, the solo sounds great and is compelling, 63 years after it was recorded.

Pete La Roca was one of the most popular drummers of his era; the Lord Discography lists sixty record dates from 1957 to 1967. Once again, the intrepid Ethan Iverson did us a public service in 2021 when he discussed La Roca with one of La Roca’s closest collaborators, the great Steve Swallow, for an article in JazzTimes.

Swallow could not have been more forthcoming with fond recollections and information about La Roca. The picture Swallow painted of a deeply serious, often contrarian musician whose deepest wish was to be a master practitioner of 4/4 swing and bebop, yet who always included rhythms and ideas from distant sources, was like a beacon flashing: more attention is due, more attention is needed. More attention should be paid to Pete La Roca1.

A full biography placing La Roca in context is beyond the scope of this piece, but several themes appear throughout:

The conversation and connection between Latin music and African American jazz and R&B.

The complex web of connections among professional musicians which result in new ideas, and new paradigms.

The jazz musician as an agent of connection and influence, even when that musician is not well-known to the jazz public. (This is a major theme for my entire Substack.)

Watch for these signposts along the way!

Pete La Roca was born Peter Sims in Manhattan on April 7, 1938. He grew up around jazz, and while attending the High School of Music and Arts (now LaGuardia) became involved in the burgeoning Latin scene, playing timbales at the Broadway Casino and in the Bronx. Often the only African-American in the band, he began calling himself Pete “La Roca”, a pun on the Greek meaning of ‘peter’ (peter=petra=the rock= la roca). La Roca, then, is a stage name, invented for use in the NYC Latin music scene; for ease’s sake, I’ll refer to him by this stage name.

In 1957, at age 19, he debuted on record with Sonny Rollins, playing on the first cut of Rollins’ A Night At The Village Vanguard, “A Night In Tunisia”. Tellingly, the first sound we hear him play is a version of a conga time-keeping pattern, while playing the first song to consciously merge Afro-Cuban and jazz traditions. In 1959, he toured Europe with Rollins and bassist Henry Grimes, leaving behind several sets of idiom-defining tenor trio.

Back in New York, La Roca met Jackie McLean in the studio for the date which became New Soil. To place Pete La Roca’s free improvisation on “Minor Apprehension” in context, let’s glance at the emergence of free jazz, a.k.a. the avant-garde, with special attention paid to the drummers.

Let’s say that the avant-garde really starts asserting itself, as a style, on record at least, with Cecil Taylor’s Jazz Advance (Transition, 1957) with Denis Charles on drums. Then it takes a major leap in public recognition with Ornette’s The Shape Of Jazz To Come (Atlantic, 1959) with the great Billy Higgins on drums. And let’s suggest, though its less provable, that Taylor’s and Coleman’s ideas had something in common with the music of Sun Ra, not a widely known figure at the time, but who could be heard on Jazz By Sun Ra (Transition, 1956), Super Sonic Jazz (Saturn, 1957), and Jazz In Silhouette (Saturn, 1958). I note that nearly 100% of the music, on all of these albums, is in tempo; is, in fact, usually in deeply swinging 4/4.

So, the earliest ‘free jazz drummers’ are Robert Barry, William Cochran, and tympanist Jim Herndon with Sun Ra; Denis Charles with Cecil Taylor; and Billy Higgins and Ed Blackwell with Ornette Coleman. These brilliant, brave, and swinging gentlemen were the drummers who took jazz the furthest in the late 1950’s.

Paradoxically, nothing these great drummers played with Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor, or Ornette Coleman would have been out of place with any excellent mid-century jazz. Their innovation was, partly, their belief in the new music they were making.

As I’ve previously explored, free jazz drumming- drummers who suspended time, who stopped playing a steady tempo, went off the grid, and instead played breath, wind, ocean swells, tides, earthquakes, and the whole range of sounds and energies free music made available- emerged very gradually and in dissimilar environments. See my posts about how Paul Motian took his first steps towards this sound.

Motian seems to have begun his journey away from steady pulse by learning Carla Bley’s out-of-time melodies on the drums; La Roca got there through Afro-Cuban music.

So La Roca’s solo, beyond sounding great and being fun to listen to, is important for two reasons:

The solo is based on Afro-Cuban vocabulary, a limitless source of rhythmic wisdom and innovation. In Afro-Cuban music, the African roots of the rhythms are very strong, and while Afro-Cuban is distinct from jazz, the two traditions are fully compatible rhythmically. As Chano Pozo told a journalist in 1948: “Dizzy doesn’t speak Spanish, I don’t speak English; but we both speak African.”2

The solo demonstrates how far in the past the roots of free jazz lie. La Roca’s solo connects Max Roach to Tito Puente, and both of them to Milford Graves3 and the furthest reaches of improvisation. It shows how the most advanced concepts are embedded within the most rigorous rhythmic concepts of 1959, bebop and Afro-Cuban clave.

Chano Pozo’s conga fantasias and Tito Puente’s timbale fanfares set the stage for a new way of improvising jazz. This was just the latest in a long history of interplay between Afro-Cuban music and African-American music; a detailed history of that interaction is a life’s work4, but here’s a thumbnail sketch:

When Dizzy Gillespie invited Cuban conguero and outlaw hero Chano Pozo to join his big band as a star soloist in 1948, Gillespie was participating in a movement already underway, a movement incorporating the sacred and secular drum music from Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic into a variety of American music practices, Gillespie, being a famous and important musician, was also an accelerant to that movement.

By 1950, the conga was being incorporated into jazz and rhythm and blues hits, blending with the 2 and 4 gospel handclaps, shuffle rhythms, and blues singing already ubiquitous. Cuban music was also enjoyed on its own, spawning dance crazes- the cha-cha-cha, ‘rhumba’, and mambo were so widespread in popularity that by the time of I Love Lucy, Ricky Ricardo was a conga-playing, orisha-praising leader of a Latin dance orchestra.

Cha-chas were often based on simple, memorable, lightly syncopated riffs, played with a ‘straight’ Cuban eighth-note; the opening riff of “El Loco Cha Cha Cha” by West Coast bandleader Rene Touzet was re-purposed by Richard Berry as the riff of his song "Louie Louie", which is as good a summary for the hidden-in-plain-sight nature of the Cuban influence on American music as could ever be5.

And that just about takes us to 1959.

Recorded in early 1959, New Soil is a wonderful Blue Note date, with all the long solos, great grooves, hip tunes, and beautiful sound that has defined Blue Note its entire history.

An uptempo 32-bar AABA tune in F minor, the melody to “Minor Apprehension” is a series of jagged question and answer phrases, which, as La Roca said “like drum stuff anyway”6. Jackie solos first, and plays a few quasi-modal phrases alternating with perfect, percussive bebop 8th notes, a long pause into his second chorus, and an air of drama, anticipation, and possibility; a little aria quote isn’t funny, it’s serious.

Throughout, the rhythm section of Walter Davis, Paul Chambers, and La Roca are in lockstep and perfect alignment; Davis’ downbeats are grounding and authoritative. Donald Byrd is more reassuring than Jackie when he enters for a few choruses.

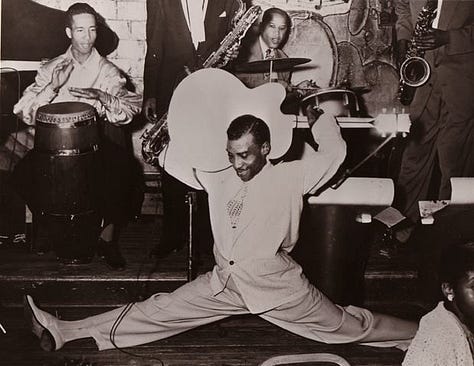

Byrd finishes, and La Roca starts his solo- no piano or bass solos, no trades. The trumpet solos ends, and all at once La Roca is off the grid. His left stick is laid across the snare drum, the snares are off, and his right hand is moving freely around the drums. The drums all have calfskin heads, so they sound like congas and timbales, further cementing La Roca’s Afro-Cuban connection.

Several brief moments of the solo are just pure percussive sound, totally avant-garde drumming: pulse-free hi hat stomps; a choked cymbal; implied tempo, quickly abandoned; a whole rhetoric of “sound is music” is present, even when we can hear the timbale solo ideas poking out.

At 6:47, La Roca plays the A section of the melody, and all four players, McLean, Byrd, Davis, and Chambers, are nailing the hard-to-play head. La Roca’s cue isn’t obvious, and the band is right there. Hmm.

…..a short cue which brings the band back in, no problem, no hesitation……An astonishing, precisely played out-head, with the horns in bebop unison and the rhythm section nailing the hits...LaRoca’s confirmation that this band never played live…….Blue Note dates were almost always rehearsed; the musicians were paid to rehearse, and many of the Wolff photos come from the rehearsals as well as the sessions…….

Was this advanced, perspicacious drum solo, a solo that anticipates a sound and rhetoric that only became familiar years later, a planned event? Did they rehearse this?

At the rehearsal, did La Roca, McLean, or someone else suggest a drum solo that was just…….rhythm and sound, a drum solo with no regard for the form or tempo of the tune, but is in the precise mood and spirit of the tune?

I think so. I think the first freely improvised, out-of-time drum solo on a widely-available jazz record was something the brilliant players on the session thought up, rehearsed, and planned. It’s a casual event, really, just a nice texture change, another cool surprise on a wonderful date with plenty of surprises. Just a little something different.

Nothing illustrates the casualness with which the musicians and record company approached “Minor Apprehension” than the boogie-woogie intro to the next tune on the album, Walter Davis Jr’s “Greasy”. It’s a post-modern juxtaposition worthy of John Zorn circa 1989.

After New Soil, which was, after all, only a recording session7, La Roca just continued. He did not develop “Minor Apprehension”- style playing, that is, pan-metric, out-of-time, sound-is-music playing. "Minor Apprehension" is one-and-done. Still, the precedent had been set, even if few noticed. La Roca's solo on "Minor Apprehension" isn't just the first 'free drum solo', it's the earliest example of a free improvisation in the modern sense that we have on a record.

In 1960, La Roca became the first drummer in the John Coltrane Quartet, though he knew that Coltrane was waiting for Elvin Jones to be available. No matter, La Roca was happy to help. He went on to play on a dozen or more classic albums led by the most advanced players of the time, including JR Monterose, Steve Kuhn, Don Friedman, Freddie Hubbard8, Ted Curson, Booker Little, Jaki Byard, Paul Bley, George Russell, Joe Henderson/Kenny Dorham and Art Farmer.

LaRoca in fact is a key connection between Paul Bley, Steve Kuhn, and Keith Jarrett. Paul Bley’s Footloose!, with La Roca on drums, was a massive influence on the young Keith Jarrett; Steve Kuhn recorded a trio date with La Roca and Steve Swallow, which both Keith Jarrett and Charlie Haden heard and remembered; Keith even sat in with La Roca in Boston ca. 1966, where La Roca was living at the time. It’s not too strong to say that Paul Motian and Pete La Roca were moving along a parallel path in the early 1960’s.

On Sing Me Softly Of The Blues (Atlantic, 1965) Farmer recorded two of La Roca’s tunes, “Tears” and “One For Majid”. The rhythm section was Steve Kuhn, Steve Swallow, and LaRoca. With Joe Henderson in the place of Farmer, this is the band on Basra (Blue Note, 1965), probably La Roca’s best-known work today.

Following Basra, there was another album as a leader, Turkish Women at the Baths (Douglas Records, 1967), a superb quartet date with Walter Booker, Chick Corea, and John Gilmore. But this was almost his last hurrah. After Turkish Women at the Baths, La Roca started driving a cab, then became a lawyer, but kept playing; Jon Pareles of the New York Times covered a gig he did in 1982 at Lush Life.

In 1997, he recorded an excellent, virtually unknown comeback album called SwingTime, produced by Bill Goodwin, and released on Blue Note, featuring Ricky Ford, Dave Liebman, Jimmy Owens, George Cables, and Santi Debriano. Everyone sounds great on Swingtime; La Roca in particular is incredible. I could imagine him forming a band at the time, getting some young players, hitting the road, and becoming a quasi-Art Blakey figure, like Art Taylor’s 1990’s Taylor’s Wailers, or Paul Motian’s Electric Bebop Band. It didn’t happen, and I’ll not speculate why.

Pete La Roca deserves recognition for his great and innovative playing; he defined the sound of mid-20th century jazz as much as anyone. He also quietly crafted a drum solo which connected radical ideas about improvisation to one of the world’s great musical traditions. That idea- connecting free improvisation to a traditional music- is part of the air we breathe now. In 1959, it was unheard of.

There’s much more to discuss with La Roca. Thank you to Ethan Iverson and Hyland Harris for help with this essay. Readers, leave comments, help fill in the gaps…

Thank you for reading!

LaRoca has already appeared in my essays. He figures prominently in my discussion of Paul Motian playing “When Will The Blues Leave?” with Paul Bley and Gary Peacock; Motian was on La Roca’s turf on that track, but managed to leave his own mark. Not an easy task. La Roca had a big turf cut out for himself in the early 1960’s.

Dizzy Gillespie to Art Taylor, Notes and Tones, 1977, pg. 132.

Milford Graves has long seemed connected to the Afro-Cuban tradition; his childhood in Jamaica, Queens was steeped in Hispanic/Latin culture; his sound seems connected to congas and timbales; clave seems present in his music; but I don’t have any specific info about his experience with Latin or Afro-Cuban music.

See Ned Sublette, Cuba And Its Music. Essential.

Thank you to Ned Sublette for directing me to this revelation, now available to anyone with an Internet connection, via YouTube. When I clicked on “El Loco Cha Cha Cha” and heard “Louie Louie”, I nearly collapsed. It was both a shock and the most obvious thing I’d ever heard.

McLean had recorded the piece as “Minor March” on August 5, 1955 Miles Davis date.

La Roca confirmed in his 1998 Modern Drummer interview with Ken Micallef that he never played live with McLean.

Pete La Roca is on Hubbard’s The Night Of The Cookers (Blue Note, 1965), where his affinity with Danny “Big Black” Rey’s percussion demonstrates his affinity for Afro-Cuban rhythms, and how seamlessly those rhythms and instruments, in the right hands, enhance a jazz performance.

Hi Vinnie

I really enjoyed your writing. I studied with Pete and he was a really deep person. It was towards the end of his life and his physical abilities were somewhat diminished, but when he occasionally would sit and play he sounded incredible. He conveyed some concepts about playing non-repetitive time based off of the ride that were extremely helpful.

One thing that may not be widely known is he was really into classical music. He had me analyze a few scores. His intention was to submerge into compositional techniques.

On the first lesson he talked about being able to instantly access an out of body mind state. He said it happened to him accidentally while was playing with Sonny Rollins and it freaked him out. He told me it took years to understand what had happened but he could freely get to that consciousness.

Just a suggestion but one of the best recordings he did in my opinion was the Coltrane live at the Jazz Gallery.

He did tell me that while he was soloing on Minor Apprehension he was always thinking of the form.

Thank!

Pete Sweeney

You do explain well where the "La Roca" name came from, and, considering that his most important years as a jazz musician saw him using that name professionally, it seems reasonable to refer to him as "La Roca". But I'll note that for the last 45 years of his life, he preferred to be known professionally as Pete Sims, and he begrudgingly let others bill him as Pete "La Roca" Sims because having some name recognition was better than having no name recognition in the very tough post 1960s acoustic jazz scene. Sims was (personally) done with "La Roca" by the time he left jazz to get his law degree in the late 1960s.