For Andrew Cyrille: Part Two

With Cecil Taylor in 1966 and solo in 1969.

When Andrew Cyrille joined pianist Cecil Taylor, Cyrille was a well-regarded young drummer starting to make his way on the scene. Though associated with some progressive musicians, including vibraphonist Walt Dickerson, bassist Ahmed Abdul- Malik, and tenor saxophonist Bill Barron, none were as radical as Cecil Taylor. After making his name with Taylor, Cyrille would be tagged ‘avant-garde drummer’, but that tag just shows the limits of our imagination.

Best for Andrew to talk about how it all started:

“[One day in 1958] Ted [Curson] said he was going to Times Square to rehearse with this piano player,” Cyrille recalls. “He said, ‘Why don’t you come on over? You never heard anybody play piano like this in your life.’ That’s how I met Cecil Taylor.

I had never heard anyone play the piano that way – the speed, the alacrity, his passion for the music, the information he had, the way he notated his music, what he asked from each of the musicians who played the music in rehearsals.

— Andrew Cyrille to Ted Panken, DownBeat, 2004

[At that first meeting], Cecil asked me if I wanted to play, and I played with him on that occasion. We hung out and became musical acquaintances and, as time went on, observed each other on the scene. Cecil would practice and hold rehearsals at Hartnett [Music School] and finally in 1964, when Sunny Murray left Cecil’s band. I was there.

Cecil knew about the work that I had been doing with people like Walt Dickerson. Ahmed Abdul-Malik, and Bill Barron. I had made records with them as well as with Coleman Hawkins. Cecil would see me and we always had a good rapport. So Cecil asked me to be part of his organization, and I said. “Sure!” That was ’64, and the relationship lasted until ’75.

—Andrew Cyrille to Harold Howland, Modern Drummer, January 1981

Cecil wasn’t who he is now…[When I met Cecil] he was a guy who was practicing and wanted to get his thing together. We’d run into each other, or he’d hear me play, and say, ‘Yeah, man, sounds like you’ve been listening to Philly Joe Jones.’ I mean, Cecil had his ear to what was going down.

We developed a spiritual relationship through our musical attraction until we began to work together regularly.

With Cecil I could do whatever I wanted. I think only twice during the eleven years I played with him did he ever say, ‘Play five beats of this’ or ‘give me three beats of that.’ He’d say, ‘Man, you know how to play the drums. Do what drummers do.’

But it was my own sense of how to do it. It wouldn’t necessarily be the same kind of rhythms my mentors would play or the way that they would parse or organize the rhythms. But then again, it was!

“So it was incumbent upon me to make sure that my integrity was as true-blue as Baby Dodds or Zutty Singleton! I did not want to do anything against the tradition of those guys, and the people from whom I learned, like Max and Art and Philly Joe, in case people might say that it wasn’t blue-blood, so to speak.

“I got my information together on every aspect of the drumset – the independent coordination, the foot-play, the dropping of the bombs, being tasty, playing in the spaces, accompanying – and I brought my information to the table”.

—Andrew Cyrille to Ted Panken, DownBeat, 2004

Cecil Taylor on Andrew Cyrille:

“Mr. Cyrille had a secret….You could take him wherever you wanted, and he had the ability to distill whatever the structures were, to go with you there, and react in the most musical way in any situation.

“He understood—and understands—about the joy of accompanying, and feeding, and being fed. He is meticulous as well as exquisite. He is the epitome of the logical, but beyond that, he’s magical.

The logical world could be painfully objective, but he is magical in the sense that he understands what the sound parameters are, and because of his exquisite taste, he makes a transition from being logical to being a spiritual healer.”

— Cecil Taylor to Ted Panken, DownBeat 2004.

Structure, openness, selfless accompaniment, turning logic into magic, and the healing power of music— Cecil Taylor has summed up Andrew Cyrille.

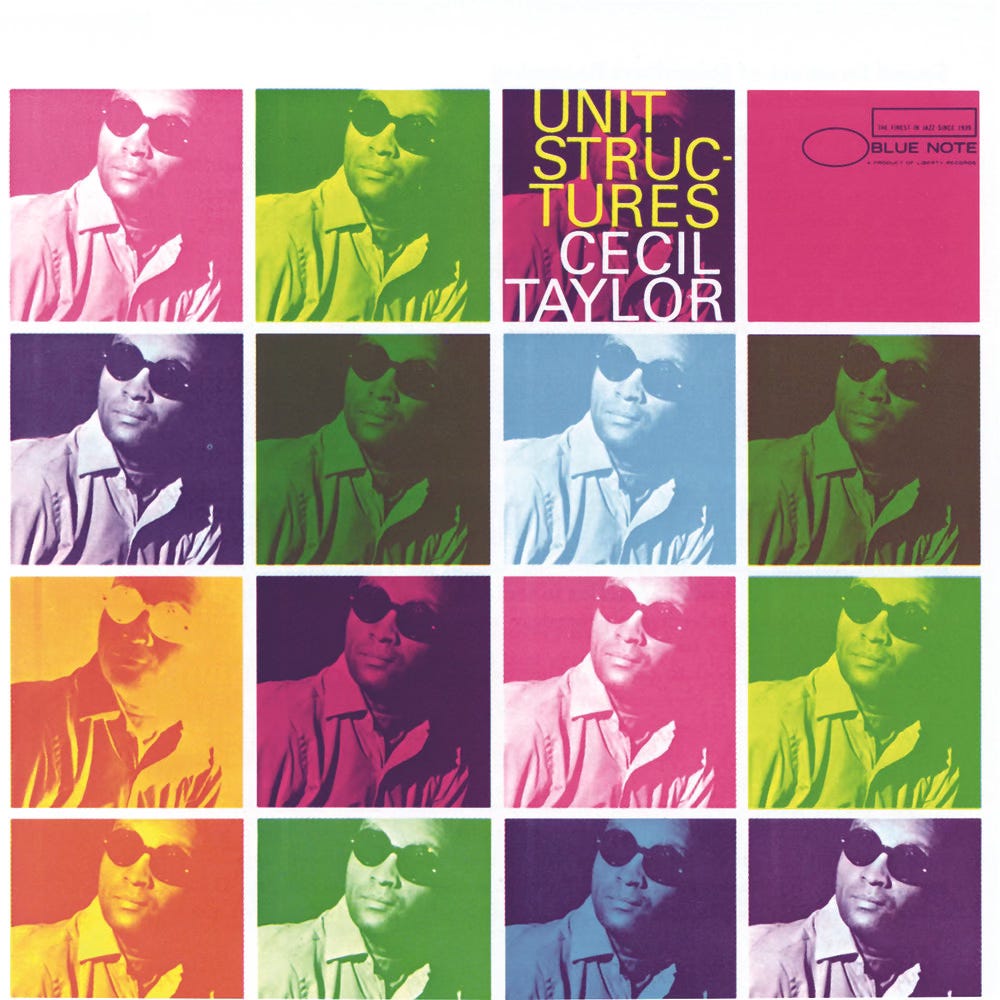

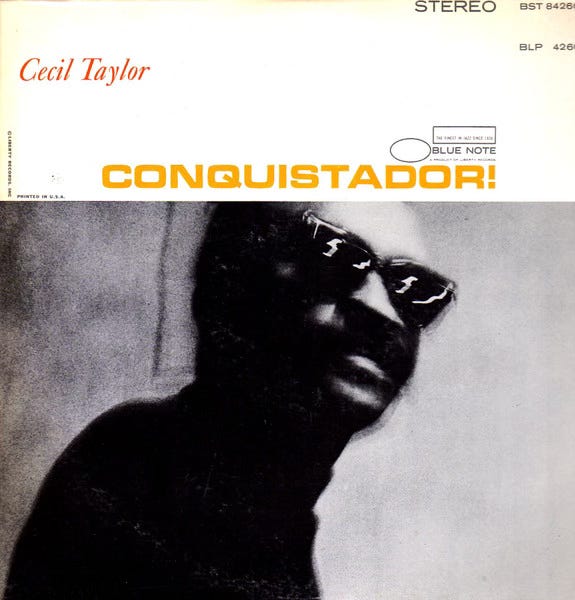

With Taylor’s words about Andrew in mind, let’s listen to their two monumental Blue Note discs from 19661— Unit Structures (1966) and Conquistador! Both are great, so stuffed with ideas, possibilities, and miracle moments that we’ll be listening for another six decades.

As Taylor suggests, there’s something wonderfully cool, down-to-earth, and transparent about Andrew Cyrille. No matter how intense the music is, you sense his calm and collected presence. Cyrille is crystal clear: it’s very simple to describe what he’s doing2. He makes his choices and moves on. This was true with Coleman Hawkins, and now it would be true with Cecil Taylor. When I’d get lost in Taylor’s barrage of melody and rhythm, I’d just listen to Andrew, and it would all make sense.

Eddie Gale: trumpet

Jimmy Lyons: alto saxophone

Makanda Ken McIntyre: alto saxophone, oboe, bass clarinet

Cecil Taylor: piano and compositions

Alan Silva/Henry Grimes: bass

Andrew Cyrille: drums

“Steps” finds Cyrille (meticulously) outlining Taylor’s composition; he’s often in (more-or-less) unison with the saxophones and piano. For the solos (McIntyre, Lyons, and Taylor), Cyrille, with lots of snare and cymbals, is playing a sort of blurred uptempo swing. Andrew and Cecil’s tight connection is sort of summarized in their startling, abrupt unison at 6:16.

“Enter Evening”, with oboe, muted trumpet, piano, bowed basses, and no drumset (at the outset) sounds fresh today, and must have been pure science fiction in 1966. Without diminishing Taylor and the group’s groundbreaking work here— this the seed from which so much of today’s music has grown— some conventions are still in place. For one thing, “Enter Evening” follows a head-solo-head arrangement3: a version of the main theme is heard again after solos (at 9:04) from Eddie Gale, McIntyre, Lyons, and Taylor. For another, we have Cyrille. He wrote his own part, he’s doing what drummers do, his integrity is true-blue. Minimal as he is on “Enter Evening”, he’s crucially enhancing the mood.

The quietude of the preceding track bleeds into “Unit Structure/As of a Now/Section”. Andrew Cyrille guides us through a series of discrete, self-contained, composed themes (units?) which materialize and then evaporate or transform. It’s over six minutes before the first solo— McIntyre on bass clarinet, with Cyrille in his uptempo, high-energy vocabulary. After Lyons’s solo (a highlight of the whole disc4) we hear some of the initial melodies5, and it ends with a turn from Eddie Gale and a grand Cecil Taylor solo. Cyrille’s quasi-unison with Taylor (at 14:52) make it clear— composed or improvised Taylor and Cyrille have a common language. A final contrapuntal squall wraps up the album’s most ambitious track.

“Tales (8 Wisps)” starts with a Taylor/Cyrille duet containing those telling little unisons— what’s composed sounds improvised, and vice-versa. Taylor is extroverted and theatrical, while Cyrille is deliberate, detailed, and cooler; they’re a perfect blend. The absence of horns on this track lets us hear the music’s engine— Taylor, Cyrille, and the (sadly hard to hear) Alan Silva and Henry Grimes— unadorned.

Conquistador!: October 6, 1966

Bill Dixon: trumpet

Jimmy Lyons: alto saxophone

Cecil Taylor: piano and compositions

Alan Silva/Henry Grimes: bass

Andrew Cyrille: drums

Anyone who likes modern jazz will love Conquistador!, since the music unfolds more-or-less conventionally, especially compared to the arranged and ambitious Unit Structures. Conquistador!, with discrete heads and solos, is shockingly contemporary: so much jazz just sounds like this now.

Much of what Cyrille is playing on “Conquistador” is ‘Latin’, more specifically, Afro-Cuban, which connects to the piece’s title. I just love Andrew’s engaging multi-directional tapestry, energetic and transparent. It’s what jazz drumming is all about. Cyrille drops out for a beautiful Bill Dixon solo, which leads to a new soulful melody6 and a Cecil solo. Cyrille, with snares off, lays his left stick across the snare and plays the rim while his right hand plays normally, something that goes back at least to Jo Jones and undoubtedly earlier. It’s a restricted, tight sound, and anticipation builds. Eventually, Andrew breaks into a full-drumset texture at 9:54, kicking Taylor into the next gear. For Cyrille to use such a timeless device with the ultra-modern Cecil Taylor is pure genius.

“With (Exit)” is sort of a ballad, with a lyrical, almost folk melody. Cyrille enters and exits, but without the scripted intensity of Unit Structures. As Dixon sings his mournful song, Cyrille joins with brushes, high energy and straight-forward. Behind Taylor and Lyons, Cyrille’s multi-directional concept7 is in something like its pure form. The 3/4 folk melody from the beginning comes back, and the song concludes, head-solo-head. Though it’s true of all jazz, this track should be better known.

Somehow, Unit Structures and Conquistador! still sound like what we mean when we say ‘avant-garde jazz’. Cecil Taylor was a pariah in some jazz circles at the time, so I’d imagine that joining Cecil Taylor was seen as a radical or ill-advised move by at least some of Andrew Cyrille’s peers. But Andrew did what he had to, and the rightness of his move is borne out by the records. The music speaks for itself.

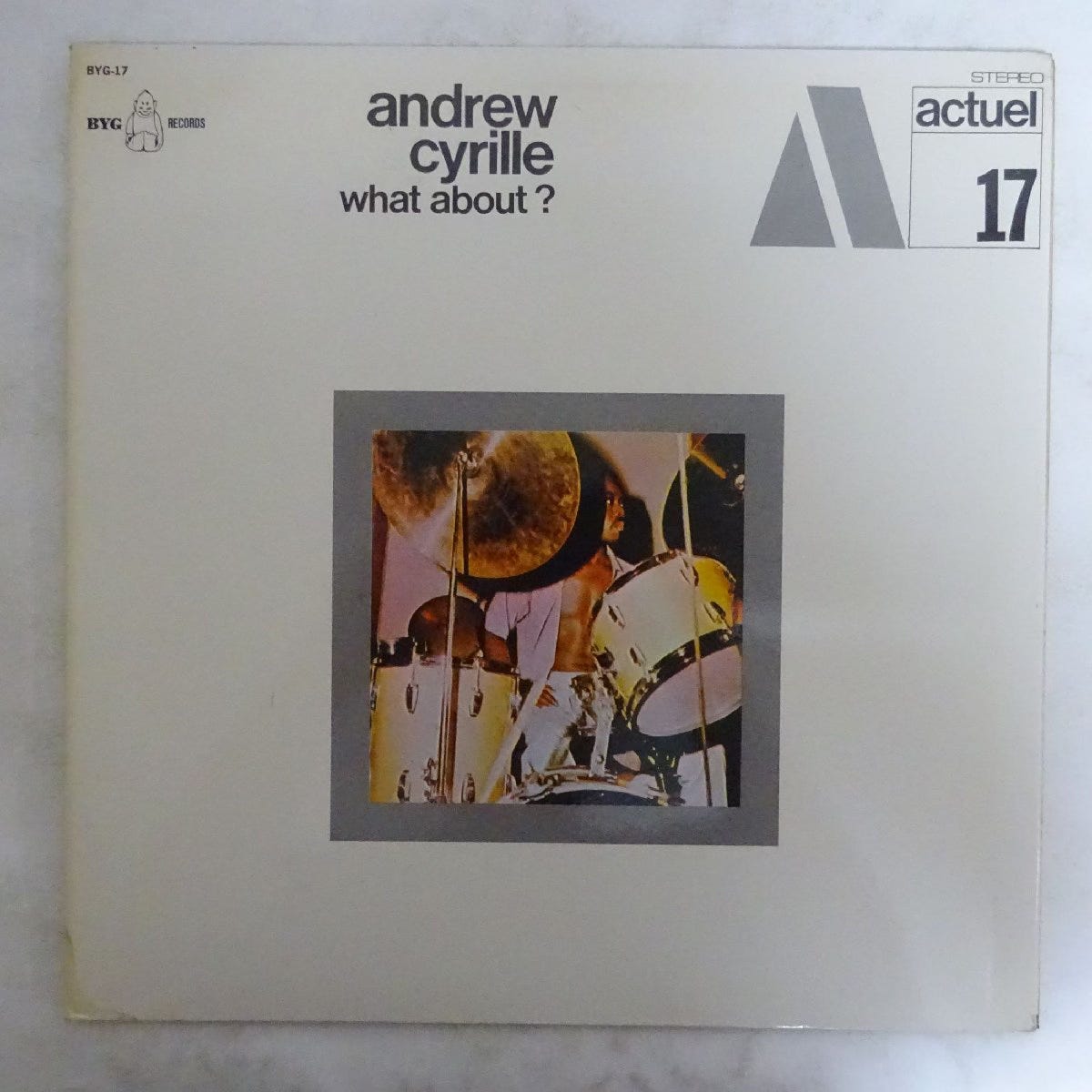

August 1969 in Paris, France was a heady time and place for jazz musicians. In July, Archie Shepp had appeared onstage with a traditional African (Turaeg) group in Algiers at the Pan-African festival, and BYG/Actuel, a French record label, recorded seemingly around the clock for a few weeks that August, giving us the first records by the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the trio of Shepp records featuring Philly Joe Jones, among others.

On August 11th, 1969, Andrew Cyrille entered the BYG studios and recorded the first— as far as I can tell— solo jazz drumset album8, entitled What About?.

No one was better suited to this task than Andrew Cyrille. Max Roach, Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, and Kenny Clarke all had other concerns, as did the avatars of contemporary culture, Elvin Jones and Tony Williams. In 1969, only serious and focused Andrew Cyrille, following his own path since he filled in for Charli Persip with Coleman Hawkins, was ready to walk up that mountain9.

What About? is a solo drumset album; not a lecture/demonstration like Jo Jones’s The Drums (Jazz Odyssey, 1973). It’s meant to be taken as you would a solo piano album.

Though it’s not nearly as concise as his recent solo work, all five solos on What About? feel like modern music, and never like a ‘drum solo’. That in itself needs to be pondered. It’s a serious achievement.

The opener, “What About?”, is Cyrille’s up-tempo multi-directional gear, a solo rendition of things we’ve heard him play with Cecil Taylor. It’s recorded gorgeously, allowing us to savor his touch and sound; the open, ringing drums just sing sing sing. It’s intense and not soft, but he’s not hitting terribly hard either. The swirls of ideas gather steam, dissolve, and reconfigure into others, the kaleidoscope just keeps turning.

“From Whence I Came” features Cyrille’s voice and breath, vocalizing and breathing in, creating wind sounds, and rolling on the floor tom with timpani mallets. It’s theatrical and evocative, and Cyrille’s musicianship and down-to-earth sense of play and fun makes it work.

“Rhythmical Space” is sort of “What About?” part 2— high-energy improvisation. The cymbal rolls are dramatic and unforgettable, and the vaguely martial feel is a satisfying contrast. There’s moments of Philly Joe scattered about, and there must be memories of Willie Jones, Lennie McBrowne, and other drummers whose names were never well-known here as well.

“Rims and Things” is our first self-explanatory title. The space Cyrille leaves between the phrases will be familiar to anyone who’s seen him play— Cyrille is an engaging performer, someone who wants to bring the audience to him. The light, humorous Cyrille is present here.

Finally, “Pioneering”, where Cyrille overdubs finger cymbals, coach’s whistle, and slide whistle over a buzz roll and single-stroke accents on the snare, is hilarious. Is this a tribute/parody to drum lessons and marching bands? I’m not sure if anyone else will enjoy this, but I love it. This is exactly what drummers do when no one’s looking. Amazing to hear a bit of near comedy after this long survey. I wonder if there’s a lot more humor in the music than I realize.

Andrew Cyrille was just 29 years old at the time of What About?, and we’re so fortunate to have him with us today. In November, Cyrille will be back at the Vanguard, this time with Joe Lovano and Dave Douglas. I’ll be there, soaking it up. There’s no end to this.

Unit Structures and Conquistador! are also Cyrille’s first studio dates with Cecil.

Saying why it works is something else!

Saying that “Enter Evening” has a ‘head’ is, of course, a bit reductive, which isn’t my intent. The shadow of head-solo-head persists on “Enter Evening”, but there’s obviously a lot more going on here, including shared vocabulary and intra-group understanding. the grand pause before the coda catches me every time; I can’t think of another Sixties track where the group just stops like “Enter Evening”.

Does anyone know what (or, more properly, if) Lyons is quoting from 9:27 to about 9:43? To me, it sounds like bits of Bird on “Hot House”.Any info would be most appreciated!

The ascending repeated note theme at 1:32 is heard— in some form— after the Lyons solo from 10:27 to about 10:40. There’s a straight-up recap at 12:01, and I’m sure many other echoes of these themes that I’ve missed. I had fun tracking down these little moments, was like preparing for a gig. Music is generally more complex emotionally and less complex intellectually than I first realize.

Taylor’s brief modal moment, starting at 7:22, really sounds like Andrew Hill, and Cyrille and Grimes/Silva suggest Richard Davis and Joe Chambers, which is certainly a lot to think about.

I notice that Cyrille’s multi-directional concept on “With/Exit” doesn’t suggest Afro-Cuban, as it did on “Conquistador”. “Conquistador” is Latin feel, “With/Exit” is

Max Roach, the founder of modern jazz drumming, would not make a full-length solo drumset album until 1978. Roach’s three unaccompanied solos (“The Drum Also Waltzes”, “For Big Sid”, and “Drums Unlimited”) on Drums Unlimited (Atlantic, 1966), are among the earliest recorded, though he’d been playing pieces like that live since the early Fifties. Roach of course was someone Cyrille remembered from the neighborhood in Brooklyn. In other words, it all comes from Roach, no matter how you look at it, but Andrew got there first.

Andrew has played and recorded solo drumset throughout his career. His most recent release, Music Delivery: Percussion (Intakt, 2023) also solo drumset, shows how far he’s developed this— it must be the most soothing drumset performance ever recorded. What About is the beginning.

Bravo, Vinnie!

Way back in ‘85 I remember seeing him with Muhal, then playing the next set with John Hendricks and Annie Ross, and then (maybe it is just the years and my imagination) a swing band in succession at the Chicago Jazz Festival. Hendricks was very enthusiastic.